Politics on Twitter vs IRL

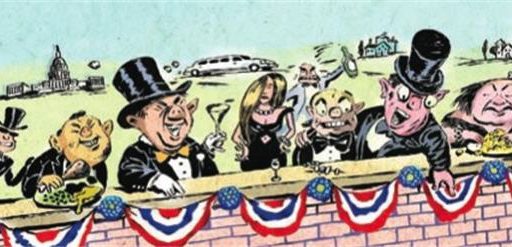

The 2020 debate on Twitter does not represent ordinary Americans. Does that matter?

There’s an interesting discussion in the latest Open Forum post about the extent to which the issues Democratic presidential contenders are bandying about in this early stage are too focused on the concerns of elite white progressives and out of touch with a base that’s more blue collar, conservative, and nonwhite.

An interactive feature at the New York Times‘ Upshot site titled “The Democratic Electorate on Twitter Is Not the Actual Democratic Electorate” shines some useful light on this. It’s long and very graphics-intense an largely defies excerpting. The, well, upshot is this:

The outspoken group of Democratic-leaning voters on social media is outnumbered, roughly 2 to 1, by the more moderate, more diverse and less educated group of Democrats who typically don’t post political content online, according to data from the Hidden Tribes Project. This latter group has the numbers to decide the Democratic presidential nomination in favor of a relatively moderate establishment favorite, as it has often done in the past.

[…]

Roughly a quarter of Democrats count as ideologically consistent progressives, who toe the party line or something further to the left on just about every issue. Only a portion of them, perhaps 1 in 10 Democrats

over all , might identify as Democratic socialists, based on recent polls.

Traditional liberals — another relatively white, well-educated bloc of Democrats — are also overrepresented on social media. They’re united with the progressive activists on the issues that divide Republicans and Democrats. They split on whether American society is fundamentally and unacceptably unjust, with liberals optimistic about compromise and satisfied with a cautious approach, and progressives demanding bolder action to redress injustice in society.[…]

Of course, the Democratic Party has moved to the left in recent years. It has moved far enough left that there’s plenty of room for a progressive candidate to win the nomination. It would be a mistake to dismiss Mr. Sanders’s chances of winning the nomination just because white progressives have generally fallen short in the past. The name recognition he earned in 2016 will be an asset that prior outsider candidates haven’t been able to count on, and so will his impressive small-donor fund-raising.

But it would also be a mistake to assume that outrage on social media means outrage throughout the broader electorate. And it would be a mistake to assume that more moderate Democrats are out of step with the party’s electorate.

There’s a whole lot more there, including a lot of interesting data visualizations, and I commend it to you.

But Eric Levitz has an interesting rejoinder: “For Democrats, Twitter Is Not Real Life. But It Could Be.” He begins by acknowledging some of the findings from the aforementioned poll:

Democrats on Twitter are weirder than they appear. The small slice of blue America that’s visible on social media is much more ideological, progressive, white, college-educated — and, above all, interested in politics — than the Democratic coalition writ large.

Online, Ralph Northam’s youthful experimentation with blackface (and/or, Klan cosplay) self-evidently requires his resignation; the Democratic base is sick and tired of neoliberal triangulation; appealing to African-American voters means making the case for reparations; and “Mayor Pete” (and his love of Ulysses) are well-known throughout the nation. But an alternative political reality prevails in the churches, barbershops, union halls, and Panera Breads where extremely offline Democrats roam. A silent (or at least, non-posting) majority of Virginia Democrats wants Northam to stay in office. For the moment, the typical Democratic primary voter supports Joe Biden, the Third Way Democrat par excellence (unless Uncle Joe doesn’t run, in which case, they’ll take the democratic socialist). The typical black Democrat, meanwhile, prefers race-neutral wealth redistribution to reparations — and if you ask a group of normie Dems what they think of “Pete Boot-edge-edge,” they’ll be liable to think you’re having a stroke.

He sees the utility in this information:

The piece, which draws on survey data from the (militantly moderate) More in Common project, serves as a corrective to punditry that mistakes the consensus views of Democrats on social media with those of the party’s base. And there’s much to be gained from dispensing with that false equivalence. The fact that Democratic voters are less “woke,” ideologically motivated, and attentive to the news cycle than they appear to be on social media has real implications in the upcoming primary fight. To name just one: Progressives who assume that Joe Biden’s many trips to the wrong side of history will inevitably condemn him to history’s dustbin are likely indulging in the pundit’s fallacy.

However, he warns

This said, if misinterpreted, the Times‘ analysis could end up promoting its own fallacies. It is important to understand that progressives on Twitter are not representative of rank-and-file Democrats. But it’s equally important to remember that the major parties’ governing agendas aren’t set by their rank-and-file voters in popular referenda. Rather, each party’s priorities are shaped primarily by its political elites — which is to say, by its most influential elected officials, activists, donors, policy intellectuals, and interest-group leaders. Such partisan elites have never been representative of their “normie” allies. For this reason, if we want to assess the relevance of extremely online progressives in “real life” political outcomes, it isn’t enough to ask whether they’re representative of the Democratic electorate; we also need to know whether they speak for their party’s reigning elite.

He argues this is true for Republicans as well:

The Republican Party’s reigning elites are

roughly as demographically and ideologically distinct from the broader GOP electorate as the online left is from the broader Democratic one. The attendees of Koch Network summits, members of Chambers of Commerce, segment producers of Fox News shows, and leaders of evangelical megachurches are more highly educated, ideological, and ideologically conservative than the Trumpian proletariat. And yet, this fact does not render the former’s views irrelevant to political outcomes in “the real world.” In fact, the preferences of conservative elites are much more relevant to such outcomes than those of ordinary Republicans.This is true in two distinct senses. First, such elites are much more effective at imposing their will on the GOP because they have the time, money, and attention necessary to punish party officials who betray their preferences and reward those who do their bidding. Ordinary voters, by contrast, can’t afford to fund lobbying operations or make big-dollar donations as individuals — and do not (generally) have enough interest in politics to form organizations capable of funding such operations collectively. Thus, the median Republican has relatively little leverage over her party’s officeholders: In opinion polls, a majority of GOP voters actually oppose cutting taxes on the wealthy and corporations, support increasing federal spending on health care, and say that the Supreme Court should uphold Roev. Wade. The Republican Party nevertheless treats cutting taxes on the rich, reducing health-care spending, and appointing anti-Roe judges to the judiciary as governing priorities — because this is what conservative elites prefer.

Secondly, the views of conservative elites are more significant than those of the typical GOP voter because, on many issues, the typical GOP voter will simply take dictation from her party’s elites. As the poll results cited above would suggest, rank-and-file Republican voters are a bit more likely to identify as “moderate” — and to express support for a heterodox mix of liberal and conservative policy positions — than their most politically engaged co-partisans. But in most cases, this moderation does not reflect a strong ideological commitment to center-right policies, so much as a lack of ideological commitment, in general.

He cites a bit of political science research to explain this seeming contradiction:

As political scientists Donald Kinder and Nathan Kalmoe (among others) have demonstrated, most voters view politics through the lens of identity, not ideology. Voters are born into families, religions, ethnic groups, regions, and economic classes — and most derive their partisan preferences from these social-group attachments. Relatively few care enough about politics to subscribe to any coherent philosophy of government. Thus, when asked to categorize themselves ideologically, many voters who have little use for such categories will identify as “moderate,” by default. Meanwhile, even self-identified conservatives tend to be partisans first, and ideologues second. Or as Kinder and Kalmoe write, “ideological identification seems more a reflection of political decisions than a cause.” In other words: The average conservative Republican doesn’t identify with the Republican Party because she is a conservative — she identifies with conservatism because she is a Republican.

In this view, then, party ID is more about tribe than ideology.

This “ideological innocence” gives GOP elites leeway to define (and redefine) the “conservative” position on a wide variety of issues for ordinary Republican voters. In the mid-aughts, opinion polls showed that Republican voters were becoming increasingly concerned about climate change, and open to government action to address it. Then, as Harvard political scientist Theda Skocpol has documented, Fox News and other organs of the conservative media began ramping up their coverage of “the climate hoax” — and that polling trend abruptly reversed. By 2009, more than 60 percent of GOP voters were telling Gallup that global warming was exaggerated. This “follow the leader” phenomenon has been especially conspicuous in the Trump era, when the Republican Party’s most influential public-facing elite have forced the “conservative” faithful to radically redefine its orthodoxy onU.S. policy toward Putin’s Russia, the relevance of personal morality to an individual’s fitness for high office, and free trade.

Yet, while the elites didn’t get their way in the primaries, they’ve still largely controlled the governing agenda:

The old guard could neither make GOP primary voters care about Trump’s heresies on trade or universal health

care , nor make them forgive Jeb Bush for his heretical softness on immigration. The party did not “decide.”But the base didn’t decide by itself, either. Subsequent events have confirmed the central importance of the GOP’s nativist counter-elite to the 2016 revolt. As we’ve seen, immigration isn’t the only issue where elite conservative opinion is in tension with the intuitions of ordinary Republican voters. But since the GOP has no “welfare chauvinist” counter-elite, the party has made no effort to translate Trump’s populist (and popular) positions on health care, infrastructure, or drug prices into policy. And even with the support of nativist elites, GOP voters have been unable to force their party to implement their preferences on immigration: Despite the president’s best efforts, a unified Republican government declined to pass restrictions on legal

immigration, or funding for a border wall during his first two years in office. In the end, on almost all issues of substantive import, Jeb Bush’s donors did decide.

That’s a lot of set-up to get back to the topic at hand:

All of these dynamics apply to the Democratic Party’s internal politics. A significant minority of Democratic voters harbor decidedly “non-woke” views on a variety of social issues. But these days, such voters’ preferences are almost entirely ignored in intra-party debates. This is because Team Blue’s social liberals aren’t merely more numerous, but also, better organized. NARAL has the resources to impose a cost on Democrats who work to curtail reproductive freedom; low-information Democratic voters who parrot right-wing talking points in conversations with pollsters do not. Meanwhile, on many issues, what the Democratic base will see as the “liberal” or “moderate” position is effectively dictated by elite signaling. When Barack Obama came out in favor of gay marriage, support for that civil right among black voters jumped from 41 to 59 percent. Finally, on those occasions when grassroots revolts stymie Democratic elites, it is generally because a counter-elite has effectively mobilized in opposition — as when labor unions and consumer groups defeated Obama’s push for the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

All of which is to say: Extremely-online Democrats don’t need to be representative of the broader Democratic electorate for their views to be of paramount importance. They just need to be representative of their party’s most powerful elites.

That’s all true, if the point is deciding who wins the party’s nomination. But the discussion in the Open Forum gets to the more important issue: motivating voters to support that nominee in the general election contest against President Trump. A nominee who spends all her time talking about Green New Deals and transgender rights is unlikely to generate a lot of enthusiasm among black voters who turned out for Barack Obama but not Hillary Clinton. And a nominee who advocates an open borders policy isn’t going to entice the blue collar white guy who usually votes Democrat but went for Trump in 2016 back into the fold.

Of course, this works both ways. While most Democrats and Trump-hating independents would likely be glad to vote for Joe Biden, his nomination would be soul crushing for a lot of young progressives and a goodly number of women. One would think the contrast with Trump would overcome those objections but, well, many of us thought that in 2016.

I am just one (of the many?) who are NOT on twitter, don’t desire to be on twitter, think that intelligent debate cannot be reasonably discussed in 280 character postings take offense to being stereotyped as “less-educated”.

Sigh. You really need to stop trying for the click bait sub-headings, James. Especially when they (a) are countered by your actual article and (b) are wrong.

The group of “Ordinary Americans” includes those of us on twitter. It isn’t exhausted by us but we aren’t some non-ordinary elite. The ~18 Million Americans on twitter represent more than the combined populations of Connecticut, Oregon, Kentucky, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Yes, twitter runs more educated, more white and younger than the population at large but it isn’t taken from a separate population.

@Bob@Youngstown: The sort of people who debate politics on Twitter, blogs, etc. are much more likely to be college educated than the typical American. It would be a commission of the ecological fallacy, however, to extrapolate from that information about any given Twitter user or non-user.

the local library still gets the national review in print form. At its height I’d be surprised if national review had more than a few hundred thousand monthly readers. which is to say probably 99% of conservatives in America never read it. But it still had an influence on the movement beyond the sheer numbers of its subscriber base. Same with Twitter. All the political journalists are on it, so it moves the discourse.

@James Joyner: @James Joyner:

OK, so I am just one person, but I value OTB because it is a “place” where we can have intelligent discussion/debate and do so in a fairly civil fashion. Because you or commentators have latitude to fully develop and explain their various points of view I am enriched, even if I disagree.

From what exposure I’ve had with Twitter the “debate” tends to be rude, crude, and unproductive toward driving understanding. Hence, my aversion.

@Bob@Youngstown:

I am no Twitter evangelist, although I am on the platform daily. I would say that it really depends on whom you follow. A huge percentage of the people in my like corner of the twitterverse are PhDs in polisci and history from whom I actually learn things and have interesting conversations. So it isn’t just a wretched hive of scum and villainy.

There is high snark quotient, however.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I second all of this.

My Twitter lists, especially my Top Reads and Foreign Policy feeds, are how I consume the medium.

Super important point here. Lists are what makes Twitter usable for any type of worthwhile communication (or research). The primary feed’s UX is garbage and, like Facebook, most likely designed to promote interactions… I mean conflict.

“far enough left”: so far they are in the left field foul section of Wrigley Field!

@Bob@Youngstown:

I don’t think debate can be conducted on social media at all, but Twitter seems far worse than other platforms.

I don’t know if progressives are representative of rank-and-file Democrats, but their views are pretty unobjectionable for the present. Nobody is saying that it’s acceptable for men under fifty to go around sniffing women’s hair. That’s not an issue. Nobody with a gay or trans child is going to be listening to both sides. That’s also not an issue for Democrats.

It’s also worth noting that the economic issues which divides elite liberals–say like how to treat testing for magnet public schools in New York–are not being played out in national politics. Nor are we listening to candidates talk about using Latina or latinx, or discussing Andrea Long Chu’s takedown of Bret Easton Ellis in the context of gay vs trans politics. Basically, the Democrats are running a very universal campaign which is causing the right to explode in paranoid fits. Try having anybody normal read the constant slew of grifters out to frighten the old, white, and paranoid,. That’s the real internet vs real life contrast.

yep.

From my experience, the problem is not only that social media in general does not reflect real life voting, but the extent in which it does not reflect it. Tim Miller, the Never Trumper Strategist, likes to point out that everybody on his Twitter was supporting Cynthia Nixon, no one was supporting Andrew Cuomo – and Cuomo trounced Nixon, even on the most liberal areas of New York.

Most of the far-left candidates that people in my Facebook supported never went beyond 1% of the vote in the first round of Brazilian elections. That phenomen seems to be worse in left-of-center circles than in the right-of-center.

Everyone on Twitter is a Pauline Kael. And not because you can find good movie criticism on Twitter.

@Tyrell: Well then thing have improved. The last time you ranted and hollered about how far left they were, they were on the far side of the parking lot. Good to see things are getting better. You should be happy–your efforts are paying off.