More On Smallpox

Earlier this month, I noted that the decades long debate about what to do with the remaining samples of smallpox virus has been been back in the news lately thanks in part to what many be an imminent decision on the matter. Since then, Susannah Locke at Vox is out with a post listing the reasons why the virus will likely never be destroyed, at least not in the foreseeable future, and it boils down to five reasons:

The World Health Organization condensed the stocks into these labs not soon after polio was eradicated in 1980, creating a balanced Cold War stare-down between the two nations. And even though it’s not the Cold War anymore, there’s still plenty of tension. Russia, after all, just declared that it’s going to kick the United States out of the International Space Station in 2020.

These two countries have been the most vocal about keeping the stocks, citing reasons related to public health. But there are also reasons that they don’t say out loud these days. In order to destroy the samples, the US and Russia have to trust each others’ word. Or simply just not care if the other nation lies about destroying them and then moves its smallpox research underground.

“I wouldn’t trust the Russians as far as I could throw ’em” Peter Jarhling told me.

(…)

After eradication, the WHO declared that the stocks in labs around the world should be consolidated into these two labs in the US and Russia (which at the time was the USSR). But no independent body ever verified that the other laboratories destroyed their samples.

(…)

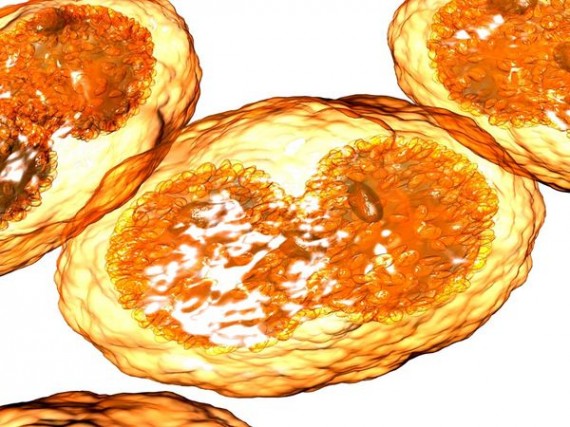

Smallpox, as far as viruses go, survives fairly well in dead tissue. And there are a lot of dead people from smallpox — at least hundreds of millions of them.

People have already found dead smallpox virus particles and DNA in bodies as old as ancient Egyptian pharaoh Ramses V, although they haven’t found any live viruses. No one knows exactly how long smallpox can survive under these kinds of conditions.

(…)

scientific curiosity does exist, and it could be an unspoken factor that has led people to continue to postpone smallpox’s kill date for over 30 years.

Even if people sequenced the genomes of every single sample, that might not be the sum total of everything that can be learned from them. The more we study organisms, the more complex they turn out to be.

For example, people thought that all heritable information in humans was contained in the genome in DNA code. But that’s not true. Now, it’s become clear that there’s a secondary level of information that is also passed down from generation to generation and influences how DNA is used: epigenetics.

(…)

One could argue that in the information and genetics age, nothing really dies forever. It just dies until the technology to resurrect it appears. And for smallpox, that time is now.

A sophisticated laboratory could resurrect smallpox right now. And at some point in the near future, anyone could. And if that is the case, then what would destroying the samples in these two labs in the US and Russia really accomplish? We might be able to destroy smallpox this year, but we won’t be able to destroy it forever.

Most of these are valid scientific arguments against destruction of the virus, but even the political arguments have merit. The cost of preserving the virus strikes me as minimal compared to the potential cost if it is destroyed and then, someday, resurrected in a world where immunity no longer exists. Indeed, if you were born after roughly 1980 you generally have no immunity at all to the smallpox virus and even those of us who did receive it may not be completely immune since there are no reliable studies regarding just how long the antibodies developed in childhood could last. Given all of that, keeping the virus samples alive strikes me as the most prudent course of action.