Proving You’re Not a Robot is Really Hard

They've gotten better at solving CAPTCHAs than we are.

Josh Dzieza explains “Why CAPTCHAs Have Gotten so Difficult.”

At some point last year, Google’s constant requests to prove I’m human began to feel increasingly aggressive. More and more, the simple, slightly too-cute button saying “I’m not a robot” was followed by demands to prove it — by selecting all the traffic lights, crosswalks, and storefronts in an image grid. Soon the traffic lights were buried in distant foliage, the crosswalks warped and half around a corner, the storefront signage blurry and in Korean. There’s something uniquely dispiriting about being asked to identify a fire hydrant and struggling at it.

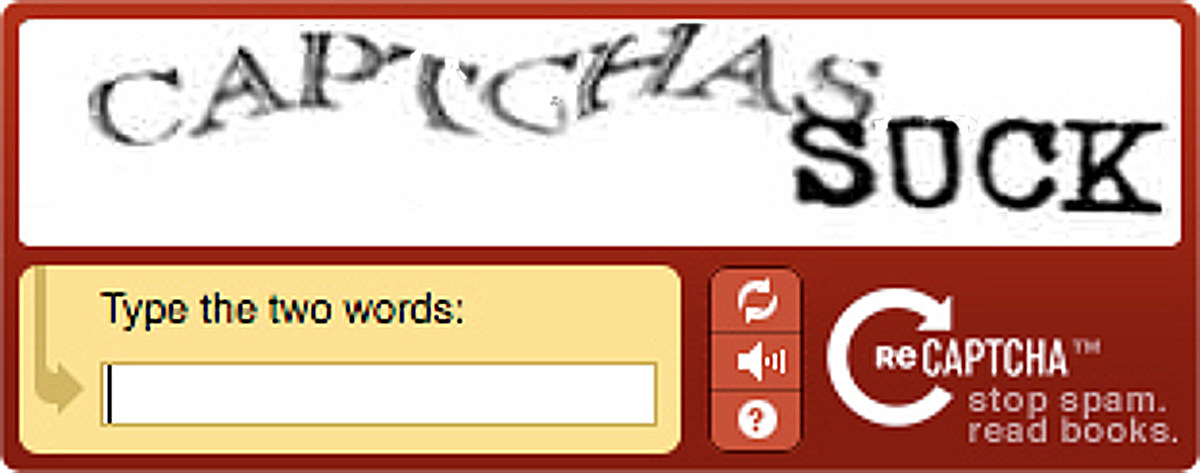

These tests are called CAPTCHA, an acronym for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart, and they’ve reached this sort of inscrutability plateau before. In the early 2000s, simple images of text were enough to stump most spambots. But a decade later, after Google had bought the program from Carnegie Mellon researchers and was using it to digitize Google Books, texts had to be increasingly warped and obscured to stay ahead of improving optical character recognition programs — programs which, in a roundabout way, all those humans solving CAPTCHAs were helping to improve.

Because CAPTCHA is such an elegant tool for training AI, any given test could only ever be temporary, something its inventors acknowledged at the outset. With all those researchers, scammers, and ordinary humans solving billions of puzzles just at the threshold of what AI can do, at some point the machines were going to pass us by. In 2014, Google pitted one of its machine learning algorithms against humans in solving the most distorted text CAPTCHAs: the computer got the test right 99.8 percent of the time, while the humans got a mere 33 percent.

Google then moved to NoCaptcha ReCaptcha, which observes user data and behavior to let some humans pass through with a click of the “I’m not a robot” button, and presents others with the image labeling we see today. But the machines are once again catching up. All those awnings that may or may not be storefronts? They’re the endgame in humanity’s arms race with the machines.

After several paragraphs detailing failed attempts to solve this problem, we’re left with this:

The problem with many of these tests isn’t necessarily that bots are too clever — it’s that humans suck at them. And it’s not that humans are dumb; it’s that humans are wildly diverse in language, culture, and experience. Once you get rid of all that stuff to make a test that any human can pass, without prior training or much thought, you’re left with brute tasks like image processing, exactly the thing a tailor-made AI is going to be good at.

The direction scientists are moving now is intriguing:

In his book The Most Human Human, Brian Christian enters a Turing Test competition as the human foil and finds that it’s actually quite difficult to prove your humanity in conversation. On the other hand, bot makers have found it easy to pass, not by being the most eloquent or intelligent conversationalist, but by dodging questions with non sequitur jokes, making typos, or in the case of the bot that won a Turing competition in 2014, claiming to be a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy with a poor grasp of English. After all, to err is human. It’s possible a similar future is in store for CAPTCHA, the most widely used Turing test in the world — a new arms race not to create bots that surpass humans in labeling images and parsing text, but ones that make mistakes, miss buttons, get distracted, and switch tabs. “I think folks are realizing that there is an application for simulating the average human user… or dumb humans,” Ghosemajumder says.

CAPTCHA tests may persist in this world, too. Amazon received a patent in 2017 for a scheme involving optical illusions and logic puzzles humans have great difficulty in deciphering. Called Turing Test via failure, the only way to pass is to get the answer wrong.

We’ve had similar experiences in the natural world with antibiotics and pesticides. Eventually, the pests evolve the become ever more resistant over time. In the end, we just create better pests.

It’s all quite fascinating. For whatever reason, I always found the old-style CAPTCHAs, with fuzzy alphanumerics, challenging. The pictographs are easier for me but annoying–although not as much as the giant pop-ups that I have to defeat in order not to subscribe to newsletters I don’t want or to comply with EU regulations on cookies.

Just don’t ask me about my mother!

I find them exceedingly annoying, in particular where they serve no purpose.

For example, there’s a website in the State of Puebla where I have to obtain some waste paper required for the state’s red tape. In addition to paying a $10 fee, it has a captcha after you enter your info, another when you attempt to pay online, and another to obtain an invoice for the payment.

I mean, do you think there are bots crawling the web randomly obtaining this paper (for which you have to input some company-specific info), paying for it, and getting invoices? And if there are, so what?

XKCD #810: Constructive

I am tired of the login captcha hoops and all the rigamarole that you have to go through now. I have talked to customer service at some of my on line accounts to allow me to have no password, but they said their systems won’t allow it. And if you make a mistake they lock you out and you have to call them. On some of my accounts I now use a very simple password that they strongly cautioned against, but I am tired of all the complicated password rules that simply make them hard to remember then I have to reset them when I forget.

I think that “no password” should be an option if preferred.

@Tyrell: When you open your No Password online banking or credit card account, please me know.

@Tyrell: Use a password manager. They’re seamless between multiple devices, including mobile.

My current best idea is that the Captcha should present a joke, with a multiple choice selection of punchlines. Pick the funny one. When machine learning gets better at humor than people, we can all just give up.

CAPTCHA I am not a Crook

a.) George Papadopoulos

b.) Donald Trump

c.) Paul Manafort

d.) Donald Trump

e.) Rick Gates

f.) Donald Trump

g.) Michael Flynn

h.) Donald Trump

i.) Michael Cohen

j.) Donald Trump

k.) Roger Stone

l.) Trump’s Tax Returns

You picked l.) Trump’s Tax Returns.

ACCESS DENIED!

NO MORE ATTEMPTS FOR YOU!

YOU ARE LOCKED OUT OF THIS ACCOUNT FOREVER!

In 1950, Alan Turing asked, “Are there imaginable digital computers which would do well in the imitation game?” (‘Imitation game’, loosely defined as 2 systems interacting where one is human and one is digital, and we can’t tell the difference.)

He stipulated that it would take more storage, speed of action and programme, then available then,…, but we crossed that chasm, years ago.

What is really scary is when these machines use the plethora of breached credentials and data (Equifax, OPM, LinkedIn,…), the only signal an enterprise gets is a successful login or account created. Now they are on the inside, with all the access of that account.

The machines are here among us today. Very few are aware of the problem (high-end B2C businesses; banks, retailers, airlines,…), and thankfully, they have become very good to disrupt, deny, degrade, destroy and deceiving this adversary. @james, I live outside Quantico, last duty station was MCNOSC & work with Shuman, if you want to dig in further.