Getting Paid for Internet Content

Who should pay whom for what?

Last Sunday, I highlighted a lawsuit against the Internet Archive by four publishing houses, claiming that their copying of books into digital form violated their copyrights. I awoke this morning to news that a federal judge had ruled in favor of the publishers.

AP (“Judge rules online archive’s book service violated copyright“):

A federal judge has sided with four publishers who sued an online archive over its unauthorized scanning of millions of copyrighted works and offering them for free to the public. Judge John G. Koeltl of U.S. District Court in Manhattan ruled that the Internet Archive was producing “derivative” works that required permission of the copyright holder.

The Archive was not transforming the books in question into something new, but simply scanning them and lending them as ebooks from its web site.

“An ebook recast from a print book is a paradigmatic example of a derivative work,” Koeltl wrote.

The Archive, which announced it would appeal Friday’s decision, has said its actions were protected by fair use laws and has long had a broader mission of making information widely available, a common factor in legal cases involving online copyright.

“Libraries are more than the customer service departments for corporate database products,” Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle wrote in a blog post Friday. “For democracy to thrive at global scale, libraries must be able to sustain their historic role in society — owning, preserving, and lending books. This ruling is a blow for libraries, readers, and authors and we plan to appeal it.”

[…]

In a statement Friday, the head of the trade group the Association of American Publishers, praised the court decision as an “unequivocal affirmation of the Copyright Act and respect for established precedent.

“In rejecting convoluted arguments from the defendant, the Court has underscored the importance of authors, publishers, and lawful markets in a global society and global economy. Copying and distributing what is not yours is not innovative — or even difficult — but it is wrong,” said Maria Pallante, the association’s president and CEO.

As much as I support the idea of the Internet Archive, I tend to think the judge got it right here. An internet-based library, like a physical library, should have to pay rightsholders for their content. Surely there’s a way to do that.

At the other extreme, though, is this:

LA Times (“California bill would force Big Tech to pay for news content“):

In the latest attempt by legislators to rein in Silicon Valley, a measure has been introduced in California that would force tech companies such as Facebook and Google to pay publishers for news content from which their platforms profit.

The California Journalism Competition and Preservation Act, announced by Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) on Monday, if approved, would direct digital advertising giants to pay news outlets a “journalism usage fee” when they sell advertising alongside news content. Additionally, the bill would require publishers to invest 70% of the profits from that fee in journalism jobs.

The bill has strong support from news advocacy groups including the California News Publishers Assn. and the News/Media Alliance. (The Los Angeles Times is a member of both organizations and supports the proposed legislation.)

“Big Tech has become the de facto gatekeeper of journalism and is using its dominance to set rules for how news content is displayed, prioritized and monetized,” said CNPA Chairperson Emily Charrier. “Our members are the sources of that journalism, and they deserve to be paid fair market value for news they originate.”

The California measure is similar to a federal bill introduced last year that would allow publishers to collectively bargain for payments from tech companies that have news content on their platforms.

News/Media Alliance Executive Vice President Danielle Coffey said she hopes Congress reintroduces legislation at the federal level “to give news publishers across the U.S. the same ability to be fairly compensated by the dominant tech platforms.”

Facebook’s parent company, Meta Platforms, and Google declined to comment on the proposed California bill but have opposed the federal bill.

Meta published a statement via Twitter in December that said it would “consider removing news from our platform altogether” if federal lawmakers moved ahead with the legislation, and that “publishers and broadcasters put their content on our platform themselves because it benefits their bottom line.”

Wicks said she wanted to improve on the federal legislation, which went the route of altering antitrust laws, to be more inclusive of smaller newspapers and focus on the basic issue of paying publishers for content.

“What we’re sort of trying to do here really is level the playing field,” Wicks said. “We just want to make sure that work [of publishers] is honored in a way as opposed to being exploited by Facebook or Google or others who repurpose that content without paying for part of it.”

Unlike on Google’s platform, which aggregates content from news sources, Facebook’s users are the ones reposting news content to its site. Even so, Wicks said Facebook still bears responsibility for how the algorithm promotes content and displays it in a way that might keep users on the platform rather than clicking through links.

Wicks was inspired by the success of similar legislation passed in Australia in early 2021, which led to digital platforms paying nearly $140 million to Australian news organizations in its first year, according to the Columbia Journalism Review. One Australian publisher estimated tech money could fund up to 30% of editorial salaries, the CJR reported.

As someone on both sides of this equation—a content producer as well as one who relies on others’ content—this strikes me as nuts.

As noted in the report, the business models of Google and Facebook are different. While they’re both data mining operations, the former is an advertising company that creates value by organizing the Internet while the latter is a social media company that allows people to share content. And they both simultaneously add value to content creators and make it harder for them to make money.

For years, Google was far and away OTB’s biggest referer and Facebook was right up there. Over time, Google’s search algorithms changed and OTB became much less prominent in their results. And Facebook made it next to impossible to automatically post our content there, so I largely stopped trying. That’s frustrating, but it’s not like either of them owe me referrals. (Not that it much matters; I stopped selling ads or even bothering to monitor traffic levels years ago.)

Unlike the Internet Archive, though, both Google and Facebook don’t simply scrape articles from sites. If I want to read a news article I find on either platform, I have to follow a link to the original platform.

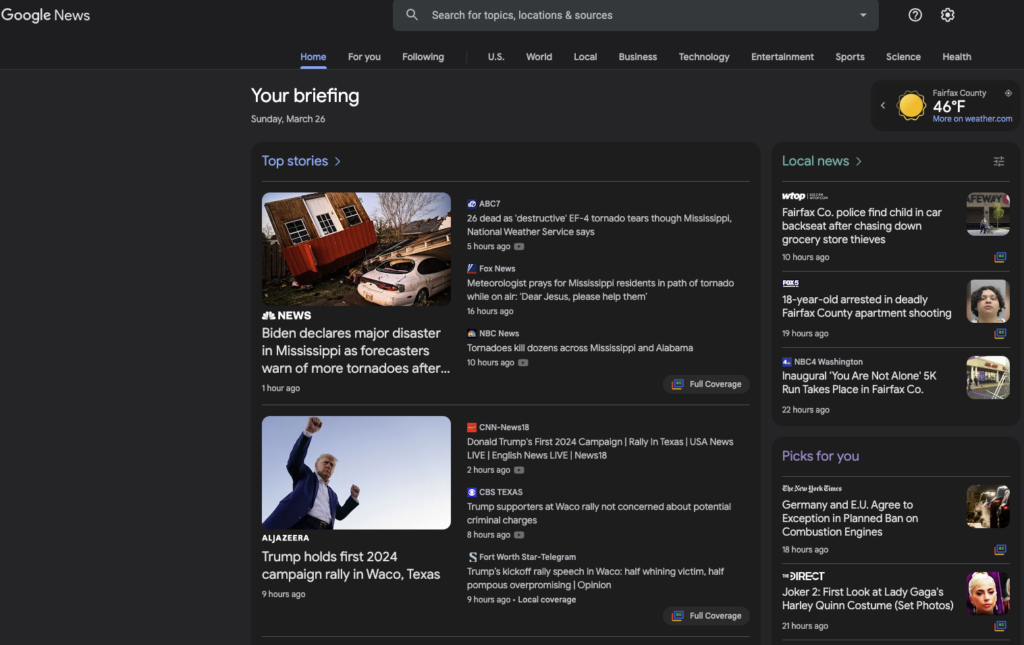

Here’s what Google News is showing as I compose this post:

It’s not a particularly well-curated list of news that interests me but it’s tailored to where I live. It’s true that, if I just want to scan the headlines, there’s no need to visit the sites of the New York Times, NBC News, or the other sources from which the Google News “front page” is crafted. But the page is filled with links directly to those stories—some of which are likely paywalled—and even branded with the names and logos of the content providers. Why should Google have to pay for this?

Facebook is weirder since the content I see on my home page is posted by people I follow and determined by an algorithm I don’t understand. But to the extent news content is posted, it’s the same thing: a link to the original source with whatever photo, headline, and excerpt the site generates. So, for example, if someone were to post a link to the aforementioned OTB post from last Sunday, they would get this:

To be sure, most people would just comment on the titular question without bothering to click through and read the article. But, hell, people do that here, too.

It seems to me that, if publishers think Google, Facebook, and other sites are depriving them of revenue through their aggregation practices, they should be able to opt out. If, say, the LA Times doesn’t want its stories indexed by Google or shared on Facebook, they should be able to fill out a form on those sites and, after some verification that it’s a legitimate request, the site’s algorithms would ensure those sites are excluded.

I couldn’t disagree more. Google takes copyrighted works that do not belong to them and profits from them. They destroy the business model of the publishers and provide no compensation.

@MarkedMan:

A) This isn’t Google. It’s the Internet Archive–creators of the Wayback Machine. They’re a non-profit dedicated to preserving digital information.

B) With the exception of their “pandemic rules”, they’ve operated just like any other library–they purchase a book at full price, and then (after digitizing), lend it to one person at a time. Just like every other library in the US.

C) With the advent of e-books, the publishers have broken the traditional model and required a license (and on-going payments) for e-books. Under that, libraries can no longer purchase a book, they can only rent it. The Internet Archive is saying “Nope. The centuries-old standard is one purchase, and endless lending.”

How it works with e-books? A one-year license (with a limit of 52 check-outs per year).

Hardcover sale (library or retail) $27.99

Consumer e-book sale $14.99

Library e-book license $55 per year

A library pays a one-time list price for a hardcover book, and can lend it out as many times as they like. A consumer pays a one-time price for an e-book and can lend their e-reader to anyone they want, as many times as they want.

A library has to pay twice the hardcover price, and three-times the e-book price EVERY YEAR. Don’t pay? The book disappears. Do something the publisher doesn’t like? The book disappears.

A hardcover book has an estimated lifetime of 40-60 years. Let’s say a popular hardcover in a library lasts 25 years. A library can pay $30 and loan that physical book to as many people as they want for 25 years (maybe as long as 60).

That exact same tome as an e-book, over 25 years, would cost the library $1,375–assuming the licensing fee doesn’t increase–and could only be loaned out 52 times per year. And, again, could have the license revoked (making the book disappear) at any time.

E-books are accessible to people who can’t travel to their local library. They’re accessible to people who are blind, dyslexic, or have trouble reading (via text-to-speech).

The Internet Archive has legally purchased a physical book–just like every other library out there. And they have added value by putting that book into a digital format that is far more accessible to far more people.

This lawsuit is not only a blatant rent-seeking money-grab by the publishers, it’s looking to eradicate the centuries-old tradition of libraries, and eradicate the firmly-establish first-sale doctrine.

And I say all of this as an author, playwright, and photographer who has put most of his content online for free.

@Mu Yixiao: But ‘first sale’ doesn’t work for digital copies. With a physical book, only one person can have access at a time. With an eBook, one sale could equal infinite free copies. The workaround is DRM. But the Internet Archive has dismantled that by illegally scanning books and ‘loaning’ them out.

@Mu Yixiao:

We aren’t in disagreement. as for “A” I was specifically referencing James’ about Google, not the Internet Archive. And I agree with you about “B”

@MarkedMan: At this point, I’m just very confused by your point, particularly in the context of this post.

Google repeats headlines adorned with links. Is this what you refer to as “Google takes copyrighted works that don’t belong to them”? Something else?