Working For The Man Every Night And Day

We're working longer than ever and working even when we're "off."

Zoë Pollock points us to two articles bemoaning the plight of the white collar worker.

Jeanette Mulvey at LiveScience (“Summer’s Here, Let the ‘Workations’ Begin”):

First there was the “staycation,” now it’s the “workation.” Americans, it seems, can’t take a real vacation anymore.

The majority of Americans expect to stay connected to their office during their summer vacation, according to Regus, a company that provides office spaces, office furniture and communications tools.

How Americans will work while on vacation varies, but three-quarters say they will stay connected in some way.

Sixty-six percent of the 5,000 people surveyed said they will check and respond to email during their time off and 29 percent expect they may have to attend meetings virtually while on vacation.

“Modern work pressures mean that more and more of us work during our vacations,” said Guillermo Rotman, CEO of Regus. “The important thing is to minimize the inconvenience by working as efficiently as we can. Rather than struggle through three stressful and unproductive hours trying to work by the poolside, you could do the same amount of work more efficiently in a single hour at a business center, with free Wi-Fi, secure high-speed broadband and professional administrative support. You then have two hours free to relax properly.”

The phenomenon of working on vacation is an extension of Americans’ larger issue of Americans struggling to achieve work-life balance, the survey found. Nearly six out of ten respondents (58 percent) say they take work home more than three times a week.

She then goes on to give other advice for minimizing the distractions, while recognizing that they’re with us to stay.

Business Insider‘s Patricia Laya (“Americans Now Think A 40-Hour Work Week Is ‘Part Time’“) adds more:

Americans consider a 40-hour work week as “part time” in most professional jobs and as a sign of a stagnant career, according to a recent study by the Center for American Progress.

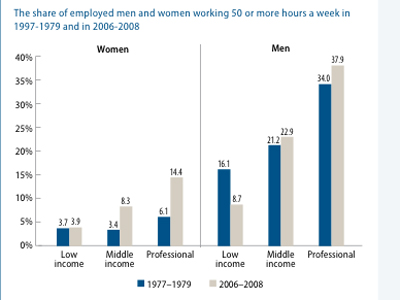

The financial reward for working longer hours has increased substantially in the past 30 years, especially for professional men.

[…]

On the other hand, while 37 percent of professional men work 50 hours a week or more, the number of middle- and low-income workers working 50 or more hours a week since 2006 has barely changed or lowered, signaling a declining job market and underemployment.

There’s even a handy chart:

Let’s leave aside methodological questions and assume for the sake of argument that these figure are accurate. Certainly, it comports with my experience. I routinely respond to emails and do other work-related activities on weekends, holidays, vacation, and even while in the hospital with sick parents or my wife and newborn babies. While occasionally annoying, the fact of the matter is that a few minutes of my time can really help keep the people who are at work–or, my boss, who never seems to not be at work–able to get things done. The office would really grind to a halt if certain key personnel–and I’m one of them–were unreachable for days or even weeks on end.

It’s doubtless true that “work-life balance” has changed as more people are employed in knowledge industries and fewer are punching a clock at the factory. But, lest we feel too sorry for ourselves, let’s also remember that with the electronic leash comes a certain amount of freedom.

First, most of us are able to spend less time in the office than we normally would because we can be reached. The notion that everyone has to be at their desk until after the boss leaves is, thankfully, gone in many if not most workplaces.

Second, while our family time is less undivided than it once was–two decades ago, most of us were simply unreachable unless we were at home or at the office–employers tend to be much more flexible than they once were. This morning, for example, I came in to work a bit late because our newborn had her 2-week checkup and mom and I both went. I doubt my dad went to any of my checkups; it would have been bizarre for him to miss work for it. Not anymore.

Third, while our personal time is less our own than it was once upon a time, our work time is less our bosses than it used to be. Workers on a factory schedule are producing for the boss the entire time they’re on the clock, minus specified lunch and bathroom breaks. Those of us who work in offices with Internet access–which is to say, most of the people affected by the increasing demand on our time–often have the luxury of taking care of personal business or taking “mental health breaks” at our leisure. So, while the number of “work” hours is expanding, it’s not a slam dunk that the amount of work is increasing along with it.

Indeed, chances are you’re reading this at the office.

The country has experienced an overall productivity gain of around 10% just since 2008, so it seems safe to conclude considerably more work is being done by fewer people, once a 20% U-6 unemployment rate is taken into consideration.

To me the most important question is: are people being compensated for their increased productivity. I haven’t noticed any significant growth in wages and salaries, suggesting businesses are bypassing their employees and transmitting those gains directly to shareholders and executive compensation, as they’ve done since the late 1970’s

This is true, but the pendulum still swings towards the employer. Example: OTB used to be a regular “mental health break” at the office.

But then the IT department blacklisted the URL. Methinks my boss prefers that my “work-life balance” should be tilted more towards work….

Well-said.

I suspect there’s a dynamic at play here which the poll fails to pick up: that Americans, and especially white-collar American men, like to brag about how much they work & see that as important to raising their social status. Whether or not they’re really “working” all that time is an entirely different story.

It’s important to recognize that the average work week has been in a long decline; the average work week now is 34.3 hours according to BLS. This post is about a relatively small sector of the economy.

Ha! I read this at lunch. The URL is also blocked on my US Government computer, I have to update myself furtively via Kindle.

Have to agree with all your comments on this phenomenon. As one of the “key personnel” at my work, I too must stay in contact pretty much all the time or things can grind to a halt (or go disastrously wrong). I find myself working over email, web, and phone during days off and vacations. On the other hand, my schedule can be very flexible when I need it to be, and since I am working many hours per week out of the office, I don’t feel guilty about checking in on politics (or whatever) a few times during the day while at the office.

Instead of eight hours of solid work at the office, five days a week, my work and non-work activities blend together a lot more these days. I may be sitting at my desk commenting on political blogs, but on the other hand I may be sending a work email while walking the aisles at the grocery store. I know that I’m still putting in 50-60 hour weeks, if you add it all up, but it’s spread out more.

This matches pretty close with my own experience. I’m a network engineer at an ISP, and most of our maintenance, turn-ups and cuts have to happen in the wee hours. So my schedule isn’t a strictly 9-5 thing. The nice part is that I can work at home 75% of the time at least. So whenever my wife gets annoyed that I have to respond to an email during dinner, I always remind her that it’s balanced by the fact that I’m around to help with our son all day. And I’m also going to have to log in and do some work in the middle of the night during our upcoming vacation.

But I also agree that wages have not gone up to compensate for all this extra productivity. The companies are basically getting more work for the same money.

Apropos to the comments on wage stagnation, this is largely an artifact that worker bargaining power has decreased relative to firms, in terms of wage negotiation. Why that is, I can only speculate.

But the notion that if you do more work (i.e. work more hours per work week), you’re guaranteed a higher wage, doesn’t have much basis in economic theory.

So, if you had a heart attack right now (god forbid) or you just quit your job, the whole company would go belly up in less than a month?

The lack of and decreasing influence and bargaining power of unions, perhaps…

Several commenters have bemoaned the disconnect between productivity and wages. There is an obvious answer: competitive pressures.

In a somewhat related concept…in the M&A business I remember when you might turn around a bid or a contract markup and send by FedEx. This gave both parties over night to think through things, confer etc. Then came faxes, and the time got reduced to hours. Now its email……”I just emailed you our response, why don’t we talk in 10 minutes, or do you just want to hold on the line until you receive it?”

Future Shock, people. We ain’t in Kansas anymore.

You may think this is true and so may the people in the office but it is not. Tim Ferris talks about this in 4 Four Work Week. He basically worked himself into a breakdown. He was working insane hours on his own company. He thought of the company as a one man operation so he had reason to believe that if he did not work crazy hours, the whole thing would fall part. He had a break down, went into hibernation for 2 weeks and when he emerged, the company was doing fine. He learned that a lot of what he did when he was ‘working’ was not really necessary.

At my last salary-slave job we had the single most important developer, the person who had been there from day 1, who had built the whole system, who had interviewed and hired the whole team, unceremoniously kicked to the curb one day. We had no time to transition, he gave his 2 week notice and the manager said ‘forget it, your out now’ ‘ (FWIW, the manager did not survive this, he was so hated by the rest of the team for how he treated the developer that he was unable to perform his job). It was a rough 2 weeks or so but we got through it and everything was fine. If ever there was a person who ‘had to be there’ it was that developer but in the end, him leaving with no notice was not as big a deal as everyone thought it would be.

We over estimate the importance of many of the tasks we do and as such, we waste a lot of effort and time doing things that are really not that important.

@OzarkHillbilly and @Jib It’s not that I’m some sort of indispensable man but rather that a lot of things run through me since, among other things, I manage the website and have editorial approval over various releases and publications. They could replace me but they’d lose a lot of institutional memory.

Ferris’ point is likely right that a lot of the urgent things we do aren’t really important. But they’re viewed as important by key stakeholders and they often “need” to get done in a timely manner. Most small and medium sized companies have no real Plan B for when key people are gone.

Presumably, even the core developer is in a different boat in that the other developers have the key technical skills. There’s not really another “me” at my company.

It’s been my experience that some workers hate their home life and avoid it at all costs by “working” late.

Once they’re promoted they force their underlings to hang out with them at work after hours to provide them with a weird sort of social life.

@ponce: Hey, I’ve worked for that guy!