Addiction and the Public Health Question

A brief foray into looking at Alabama state policy on fighting addiction.

(Sometime a quick take ends up not being so quick….).

Via AL.com: Alabama could soon make it harder to get addiction treatment, doctor says.

Many patients must travel long distances to seek care, Eaton said. Requiring patients to visit the doctor every two weeks or ween off medications for anxiety as a condition for receiving buprenorphine could discourage people from seeking care, she said. That could increase the number of overdoses.

In a statement, members of the Alabama Board of Medical Examiners said legislators required new rules to prevent the abuse of buprenorphine. The treatment contains an opioid and naloxone, which counters the effects of the opioid. Users can feel high, but the sensation is muted compared to heroin or fentanyl, according to Harvard Medical School.

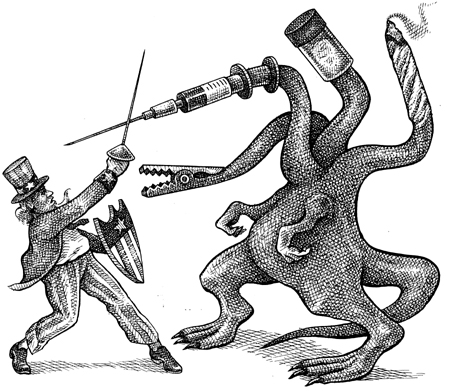

What is striking to me about this story is that it tracks long-term, ill-conceived ways of dealing with addiction in the United States. That is: treat addicts like criminals (or, at least, barely worthy of help) and create pathways to treatment that disincentivize that treatment. Moreover, the main motivator is not public health outcomes, but instead operating from some alleged moral high ground. It makes me think of needle exchange programs, which have been demonstrated to cut down on HIV and hepatitis infections.

Alabama has long had the highest number of opioid prescriptions per capita, but those numbers have fallen in the state and across the nation in recent years. Although prescription opioids once drove the overdose crisis, they have now been overtaken by heroin and fentanyl sold on the street. Eaton said state officials recently announced that fentanyl had been found in illicit drugs passed off as Adderall, methamphetamine, cocaine and marijuana gummies.

[…]

“There is a bit of a disconnect in what I’m hearing at the state level is driving the crisis and the response, which is tightening restrictions on physicians,” Eaton said.

In addition to creating barriers for patients, Eaton said the proposed rules could prevent some doctors from prescribing buprenorphine. The changes to federal law were supposed to make it easier for family doctors, obstetrician/gynecologists and others to treat addiction.

“My main concern is that patients will not have access to care, the most vulnerable,” Eaton said. “And that providers who are primary care providers who are well-positioned to respond to this are already burned out after the last few years and then we give them multiple pages of new requirements. The last thing we need are fewer doctors prescribing buprenorphine.”

I will note, the story is about the proposed change, not one that has been instituted.

I tried to find additional coverage on this topic, including what the motivations might be for the proposed rules. Instead, I found another AL.com piece from last July reporting on another example of regulations making treatment more difficult: New Alabama rules on telemedicine hurt opioid users who need help, says startup founder.

The operation, dubbed Alabama Airdrop, was needed to comply with a law passed earlier this year regulating the practice of telemedicine in the state. The law requires physicians to see patients in-person at least once a year and sparked a scramble by Bicycle Health – a telemedicine startup focused on opioid addiction. They found a partner, Aletheia House, to help them organize and host the check ups.

[…]

Patients who might have feared being seen at an in-person clinic could log on without leaving home. The company provides access to medication alongside counseling and peer support.

It’s patient load in Alabama swelled to more than 500. But the telemedicine law signed by Gov. Kay Ivey in April has halted its plans in Alabama. For months, Bicycle Health staff have tried to help patients find local doctors who can prescribe Suboxone, but only about 10 percent found new providers.

Look, I am insufficiently expert to know if having one in-person visit is vital or not. On the one hand, it sounds reasonable. On the other, it is my experience that when it comes to doctor’s appointments linked to medication maintenance, the visit is wholly about talking, so whether one is in the same room or not seems to matter little.

In general, I think that the attitude about addiction is that since it is self-destructive (and often linked to consuming illegal substances) addicts are not fully worthy of treatment (indeed, many think they should simply be punished).

While early in my life I took a prohibitionist view of certain substances, I change my mind pretty quickly when I actually confronted the subject in research and teaching (while I do not focus on the politics of the drug war, per se, it hard to study Colombia* and to teach courses on US-Latin American relations without dealing with the drug war). Without any doubt, the cost of treating the abuse of drugs as a “war” is a waste of money. It does not result in the desired outcomes and it costs one heck of a lot of money.

So, rather than a war paradigm, I have long advocated for a public health approach. And while there has been some progress in these areas, as the above notes, we still are too focused on the worthiness of those receiving help instead of just figuring out the best ways to reduce the effects of addiction.

*The amount of money the US poured into fighting the cocaine trade in Colombia, to mention Peru and elsewhere in the region, is obscene, especially when one looks at the lack of efficacy of the policies and the very real collateral damage it created.

As some may have noticed I don’t have a lot of respect for virtue signaling because I care about results. Treating addicts like criminals is that same instinct, so deeply ingrained in Americans, to favor moral posturing over real world effects.

So much this.

This is one of the areas where our cultural focus on binaries (i.e. “just say no”) does so much harm. The best addiction interventions occupy the space of harm reduction (acknowledging the fact that there will always be harm from addiction and that some people will always take drugs, then dealing with it) versus harm elimination (the idea that we can successfully eliminate drug use in a zero-sum equation).

This is also an area where social conservatism definitely conflicts with fiscal conservatism–in so much as that mitigation approaches most likely, over the long term, reduce the economic costs of illegal drug use. Unfortunately, we (as a culture) are far more interested at social punishment than fiscal responsibility (no matter what the rhetoric of a party is).

For my greatly oversimplified take on these types of proposals, they’re simply another variation on demanding that people with no shoes needing to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. We do this on a bunch of social problems.

Criminalizing addiction hasn’t worked. Seems dumb to double down on it.

I do think a lot of doctors were not considering the addiction risks of opioids carefully enough, because of a major industry wide advertising program minimizing the risks, but this is not the solution.

Its always a balancing act but it makes some sense to have ways to track how we are ordering narcotics for out pts. Mom states are doing that. When it comes to actually trying to stop drug abuse and its harms we have always heavily emphasized the war on drugs and only occasionally emphasized treatment. Even when we do there can be hurdles. I dont actually think that one visit in person a year for an addict is so awful, but we do a number of things to make it more difficult like requiring a special DEA license to order suboxone (and i think also buprenorphine). You can order all of the fentanyl you want with a regular DEA number but if you want to treat people for addiction you have another hoop.

I think at least some of it is due to not understanding treatment for drug addiction. People concentrate on the recidivism so decide it sent worthwhile. However, treatment has pretty good initial success rates. If we were talking any other chronic disease and we said treatment can give you 5-7 years of disease free time, then you might relapse and need treatment again, followed by another long period disease free it would be seen as pretty successful. However, a lot of people cant accept this as they turn into a moral issue and abstinence is the only acceptable approach, coupled with the war on drugs.

Steve

@steve:

Every now and then I come here and am given a genuinely interesting insight. You’re absolutely right. Thanks.

Looking to a state like Alabama for anything resembling an intellectual approach to a problem like drug addiction is folly.

Everything is about money. Our go-to is punishment because we need ordinary citizens to see the harsh treatment we give those folks so that those people stay on the straight and narrow and remain productive and frightened FTEs.

It’s the same reason we don’t do anything about homelessness – walking, talking examples of where you could be if you don’t comply.

America decided long ago that the money interests were going to be in charge.

To devote serious thought and time pretending science will drive decisions like this only serves to support the system.

If there will ever be change, we need to be calling it out for what it is.

Alabama once again treating their people with ignorance. I mean…hope and prayers.

@matt bernius: I don’t see them in conflict as the socons always play the short game to rile up the base costs be damned. The fincons are playing a long game of eliminating any government programs that help anyone.