Amazon Killing Libraries?

The quasi-monopoly power of the world's largest bookstore is problematic. Maybe.

The most-read story at the Washington Post this morning was Geoffrey A. Fowler‘s “Want to borrow that e-book from the library? Sorry, Amazon won’t let you.” It was not exactly the story I was expecting.

Mindy Kaling has gone missing from the library.

I was looking forward to reading the comedian’s new story collection, “Nothing Like I Imagined.” So I typed Kaling’s name into the Libby app used by my public library to loan e-books. But “The Office” star’s latest was nowhere to be found.

Fowler could scarcely have picked a less powerful example to evoke my sympathies had he tried but I pressed on.

What gives? In 2020, Kaling switched to a new publisher: Amazon. Turns out, the tech giant has also become a publishing powerhouse — and it won’t sell downloadable versions of its more than 10,000 e-books or tens of thousands of audiobooks to libraries. That’s right, for a decade, the company that killed bookstores has been starving the reading institution that cares for kids, the needy and the curious. And that’s turned into a mission-critical problem during a pandemic that cut off physical access to libraries and left a lot of people unable to afford books on their own.

So, that was something of a twist. I somehow had no idea that Amazon was a publishing house in addition to a distributor.

Many Americans now recognize that a few tech companies increasingly dominate our lives. But it’s sometimes hard to put your finger on exactly why that’s a problem. The case of the vanishing e-books shows how tech monopolies hurt us not just as consumers, but as citizens.

So, again, Amazon’s controlling of how Mindy Kaling’s book is distributed is hardly a threat to the intellectual life of the Republic, much less the common weal. But quantity has a quality of its own.

You probably think of Amazon as the largest online bookstore. Amazon helped make e-books popular with the Kindle, now the dominant e-reader. Less well known is that since 2009, Amazon has published books and audiobooks under its own brands including Lake Union, Thomas & Mercer and Audible. Amazon is a beast with many tentacles: It’s got the store, the reading devices and, increasingly, the words that go on them.

Librarians have been no match for the beast. When authors sign up with a publisher, it decides how to distribute their work. With other big publishers, selling e-books and audiobooks to libraries is part of the mix — that’s why you’re able to digitally check out bestsellers like Barack Obama’s “A Promised Land.” Amazon is the only big publisher that flat-out blocks library digital collections. Search your local library’s website, and you won’t find recent e-books by Amazon authors Kaling, Dean Koontz or Dr. Ruth Westheimer. Nor will you find downloadable audiobooks for Trevor Noah’s “Born a Crime,” Andy Weir’s “The Martian” and Michael Pollan’s “Caffeine.”

So, again, it would be really fucking helpful if Fowler would point to a single book that matters. I’m a fan of Trevor Noah but it’s hardly a crying shame if poor people can’t download the e-Book version of his latest musings. Surely, there are better examples from the “more than 10,000 e-books or tens of thousands of audiobooks” Amazon is bogarting?

Amazon does generally sell libraries physical books and audiobook CDs — though even print versions of Kaling’s latest aren’t available to libraries because Amazon made it an online exclusive.

Those. Bastards.

It’s hard to measure the hole Amazon is leaving in American libraries. Among e-books, Amazon published very few New York Times bestsellers in 2020; its Audible division produces audiobooks for more big authors and shows up on bestseller lists more frequently. You can get a sense of Amazon’s influence among its own customers from the Kindle bestseller list: In 2020, six of Amazon’s top 10 e-books were published by Amazon. And it’s not just about bestsellers: Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing, the self-publishing business that’s open to anyone, produces many books about local history, personalities and communities that libraries have historically sought out.

While that’s niche content that the average poor citizen or child is decidedly unlikely to check out, that at least gets us near something interesting: content that would otherwise be valuable that simply isn’t available because of oligopoloy power.

In testimony to Congress, the American Library Association called digital sales bans like Amazon’s “the worst obstacle for libraries” moving into the 21st century. Lawmakers in New York and Rhode Island have proposed bills that would require Amazon (and everybody else) to sell e-books to libraries with reasonable terms. On March 10, the Maryland General Assembly unanimously approved its own library e-book bill, which now heads back to the state Senate.

Given that this is where my mind had already gone independently, I’m amenable to the idea. Essentially, we’d do with e-books and audio-books what has happened (albeit, I believe, organically?) with the music business and ASCAP and BMI. There, though, there’s a more obvious equity interest. It’s not fully obvious to me why Amazon shouldn’t be allowed to decide which of its content be made available for free sharing. (There’s a much more obvious case, though, for regulating Amazon’s horizontal integration—although I’m not sure who would finance e-books and audiobooks for non-bestsellers.)

Amazon declined my request for an interview. “It’s not clear to us that current digital library lending models fairly balance the interests of authors and library patrons,” said Mikyla Bruder, the publisher at Amazon Publishing, in an emailed statement. “We see this as an opportunity to invent a new approach to help expand readership and serve library patrons, while at the same time safeguarding author interests, including income and royalties.”

Amazon announced in December it is in negotiations to sell e-books to a small nonprofit called the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), which makes tech for other libraries. But those negotiations don’t include Audible audiobooks and Amazon’s trove of self-published books. And even if that deal happened, it still wouldn’t help most American libraries, which buy and distribute e-books through the maker of the Libby app — a company called OverDrive.

OverDrive chief executive Steve Potash told me he’s had “ongoing dialogue” with Amazon Publishing. “As part of our dialogue, we communicated our willingness to innovate in an effort to support their business strategy,” he said. Amazon said it was in touch with OverDrive but not discussing operational details like with the DPLA.

This particular complaint is sufficiently arcane that I don’t know that I have an opinion. I’m not sure why it’s Amazon’s problem that OverDrive doesn’t deal with DPLA. Or why I should care that Amazon’s vanity press content isn’t available to libraries.

It’s one thing to haggle over business — but another for Amazon to have the power to unilaterally force libraries to stay in the 20th century. It’s a price we pay for letting Big Tech get so big.

Again, I really, really want to be sympathetic to this argument. As much as I like Amazon as a company—it has made my life simpler in a variety of ways—I think trust-busting is a vital government function. There are surely ways that Amazon is squeezing publishers and therefore authors in a way that’s bad for society. But it’s not obvious how this particular practice is hurting us in a meaningful way.

Finally, long after most readers would have given up, we get to it:

Since the 1980s, lawmakers have focused on one main way to measure the harm caused by monopolies: Are prices going up for consumers? That’s been a gift to Google, Facebook, Apple and Amazon. In many cases, they can argue their massive scale has made prices go down or even made things free.

But we’re not just price-sensitive consumers — we’re also citizens. We need products that are made fairly, serve our needs and are equitably distributed. Groundbreaking government antitrust lawsuits filed in late 2020 argue Google’s monopoly hurts us because it’s blocking competitors and prioritizing its own inferior services. In my own investigation, I found Google search results are getting worse as it puts its own business ahead of our interests.

Libraries losing e-books matters because they serve us as citizens. It’s easy to take for granted, but libraries are among America’s great equalizers. Benjamin Franklin helped found one of America’s first because he realized few individuals could afford a large enough collection to be well-informed.

Granting that I’m relatively affluent, Amazon has actually had the opposite effect for me: they’ve made books, particularly used books, so cheap that I tend to buy any book that I want to read so that it’s part of my personal collection and I’m free to annotate it as I please.

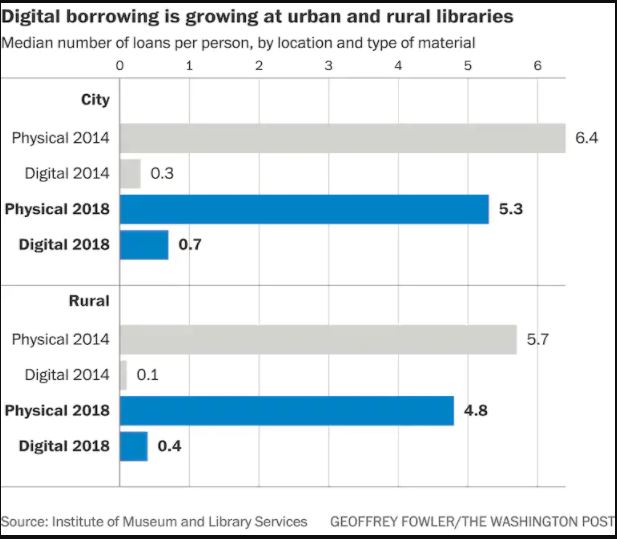

Today, the public service of libraries includes digital collections. They’re a hit in urban and rural areas alike: As of 2018, about 90 percent of American libraries offered online loans. The covid-19 pandemic made digital collections only more critical — several libraries told me e-book and audiobook checkouts surged by 40 percent or more in 2020.

You can check out an e-book or audiobook by going to your library’s website and entering your library card number. Once you find a book that’s available, you can download and read it on a dedicated device such as the Kindle, through the Web, or on a smartphone or tablet with an all-in-one app like Libby. When your loan is over, the digital copy disappears.

“Imagine if you were put out of work by covid, and you want to read a book about developing your skills. You don’t have the economic wherewithal to get that book yourself — but you log into the Libby app and can’t find it,” says Michael Blackwell, director of the rural St. Mary’s County Library in Leonardtown, Md.

The Internet has, of course, given us access to a lot more information — but also made it possible to erect new walls around some of it.

Well . . . sure. But people have a right to make a living off of their work. And most of these works wouldn’t even exist without Amazon. Dean Koontz and company would have other publishers but the self-published content exists solely because Amazon makes it phenomenally easy to be a “published author.”

“Society pays a huge price,” says Michelle Jeske, city librarian at the Denver Public Library and president of the Public Library Association. “How many different platforms does a person have to subscribe to to be able to read all the things they’re interested in? You used to be able to just do that at the public library.”

Amazon treating digital collections differently than print is a “particularly pernicious new form of the digital divide,” the American Library Association told Congress.

Another problem: Libraries can’t archive for posterity what they don’t have access to.

Tech rights group Fight for the Future made an interactive guide called Who Can Get Your Book that explains the ways libraries are being left out.

Here, I’m more sympathetic. But this is an increasing issue for all of us, right? Content of all forms has become incredibly diffuse and there’s only so much of it I’m willing to subscribe to access. It’s not like libraries have unlimited budgets. Hell, not even the Library of Congress can possibly archive everything.

Nobody is arguing libraries should get freebies from publishers and authors. In fact, libraries usually pay more than we do for e-books — between $40 and $60 per title and as much as $100 for a popular audiobook. And unlike print books, which libraries can loan out to one person at a time again and again, e-books often come with digital locks that make them expire after a certain number of loans or a set period of time.

These terms have caused tension between libraries and publishers. Many librarians worry the price and terms that come with e-books aren’t sustainable, but most agree providing access is their overriding concern. Some publishers, meanwhile, say easy access to library e-books — just a few taps in the Libby app — hurts their sales. Libraries counter that they’re a net positive, not only because libraries buy so many books themselves, but also because they’re an effective way to market products to customers who also buy books and audiobooks.

I’m more sympathetic to the equity argument than the notion that “libraries” have a more nuanced understanding than Amazon as to how best to maximize profits on their copyrighted materials.

Again, this is the strongest argument:

“The key is that Amazon is the umpire and the player at the same time,” said Matt Stoller, director of research at the American Economic Liberties Project, a think tank that’s critical of Big Tech monopoly power.

We should naturally be alarmed at this much concentration of power. I just wish we could point to something other than access to marginally-important books as proof.

Well, you’re using “what’s important to James” as a proxy for “what’s important to humanity”. The authors and books mentioned are all very popular, and thus important, to lots of people. Books that have “stood the test of time” by and large are older, and thus not really anything that’s high-volume.

Amazon is doing with books what is also being done with video and music. I prefer to have physical copies of all three, because those physical copies are mine to do with as I please. E-books are for “read once” type material, precisely because they lock me into both a vendor and a technology, and once either of them declines to continue, I’m screwed, and I don’t have my “book” any more. No, I don’t like it. Not at all.

AND, I get their problem with libraries. Libraries are a much bigger threat to an online-distributed product than to a physically distributed one, because the friction is so much less.

What I would like to see is

1) we work out a “non-fungible token” domain for ebooks, where publishers such as Amazon can be sure that a library has only a couple of copies of a popular title, and thus a waiting list for access to that title. Then

2) we pretty aggressively sunset restrictions, so that books that have “stood the test of time” are more widely available, and not locked in to a vendor and/or technology.

Libraries are so much more than books.

I was in Seattle 3-4 years ago and had the pleasure of visiting their Library. (Designed by a name-brand Architect, it’s a small bit of Archi-Porn.)

I was astounded by the number of people using it, and the diverse services they were able to take advantage of.

At the end of the day, the issue is the ability of Amazon, in this case, to use its market power in one sector of the economy to enter, buy market share and become a significant, if not dominant player in those sectors. Amazon has repeatedly demonstrated the willingness to entice small business partners till they become dependent on them and then squeeze them on margins, increased costs and even directly competing with the independent amazon store, with amazon branded products.

Frankly, that isn’t healthy for the economy and the ebook/public library kerfuffle is minor it is representative of what amazon’s business plan is.

I’d be more concerned, but we’ve overestimated the Amazon effect before. It must have been close to 10 years ago I was giving a speech to independent bookstores and I made the prediction that while Amazon might kill Barnes and Noble, the hardy independents would survive. Cue applause.

No one believed me, but then again, I didn’t believe myself. For the record, I had no idea, I just pulled that out of the air because as usual I hadn’t really thought about the speech so I was pandering. But it turned out to be true – Indies are doing fine. I was a prophet by virtue of refusing to prepare a sensible speech.

Amazon did not kill the bookstore, Borders died by its own hand, and Barnes and Noble made a series of bad decisions so they could well go next.

One other small point: B&N also abused their near-monopoly power when they had it. For example, most people don’t know this, but B&N has veto power over cover design. When GONE came out in the US it had a godawful cover acceptable to B&N. When the same book came out in the UK, Waterstone’s let the publisher decide on the cover.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that B&N meddling cost me six figures at the very least.

@Michael Reynolds:

For about 15 years, Amazon has wielded a fair amount of clout over what publishers of print and audio books will and will not produce. Quite some years ago, I had an interesting conversation with an editor at an audio book house, and she told me that they couldn’t do certain books because Amazon said no. Now these weren’t controversial titles, just standard midlist fiction. Neither she nor I could discern any pattern to Amazon’s choices.

@Jay L Gischer:

Sure. But there’s no great societal loss if they’re unable to read them in the way that there would be if, say, Barack Obama’s latest book (also mentioned in the story, but as available) were being blocked.

@Sleeping Dog:

Agreed. I just don’t think a very strong case was made in the piece, even though I was hoping for one.

@CSK:

I find that surprising. Hmm. It’s bizarre because Amazon has some of our old series from the early 90’s still up, and they haven’t sold in years. Literally everything outsells the OCEAN CITY series, it’s a complete waste of cloud space.

@Michael Reynolds:

Beaverdale Books is perhaps my favorite retail shop.

@Michael Reynolds:

Well, it was strange, and, as I said, neither of us could discern the rationale behind the choices. Some of the books on the “no” list were ones that had sold quite well in hb and pb, and some weren’t. Nothing was what any reasonable person would consider objectionable.

I am concerned about Amazon and public libraries.

Amazon has a detailed history of anti-competitive Big Foot behavior.

The lending library model where you did not have to personally own a copy of a book, but could access it for the low, low price of signing up for a library card is astonishingly effective.

That library model, if it dies, would be a massive and hugely distorting move towards absolute ownership rights.

The article is classic bait and switch. Amazon “publishes” a tiny proportion of the ebooks it sells. For the rest, it has no say on if and how those are made available to public libraries (I self-publish my ebooks on Amazon and also via other channels that distribute to public libraries).

If anyone deserves criticism it’s the big publishing houses which are imposing a cost structure for ebooks on public libraries which is costing them significantly more than hard copy books.

@de stijl: Yes. But where’s the evidence that “the library model” is going away? If a library buys a physical book, it massively expands the number of people who can easily read that book–but still only one person can possess it at a time. With e-books and audiobooks, there has to be some sort of software coding that disables copying or, otherwise, it’s Napster from the 1990s—one person buys and thousands get it free. That’s not a sustainable content production model.

Trevor Noah or Mindy Kaling may not be salient to me, but either of them might well be the author that prompts someone to sign up for a library card for the first time. When we were kids, one of my brothers wasn’t interested in reading for pleasure at all, while my mother, myself, and my other brother were all voracious readers. The three of us would go to the library every two weeks and each bring home a stack of books and my nonreader brother would hang out bored.

Until he discovered YA sports biographies. Once he realized that he could read the life stories of his athletic heroes, it was a total game changer.

You can’t predict what will get people in the habit of reading.

@James Joyner:

The evidence that the library model is going away is publishers increasingly denying loan rights to libraries.

And the fact that one publisher has the funds to buy up all competitors on a whim on a Tuesday afternoon as an afterthought.

Is that practice likely to expand or contract given how content is now being peddled?

The current media model is inexorably trending towards rent over borrow. Pay for access.

Bezos should learn from Carnegie when it comes to libraries.

@James Joyner:

I have the privilege of owning books I treasure. Many do not.

You would deny knowledge and insight due to economic status.

Profit maximization may not be the optimal civic good.

“It not affecting me, so I don’t give a f**k.” Applying that same theory to voting rights, social policy, economic policy, etc., etc. brings us to “how the hell could 74 million people vote for Trump?” Keep up the good work!

Perhaps they have branched out, but my perception was that the “publishing” business Amazon is in is providing tools and channels for people who can’t get a deal, or a deal they like, with a traditional publisher to self-publish. For example, they don’t compete with the traditional publishers for the next big book from Stephen King, with advances and editing, and layout, or organizing promotional tours. Kaling’s “book” is a collection of stories, available to listen or read online. For free if you’re one of the 100 million Prime members. It does not appear to be available in any other format. She has a number of other Kindle-only titles for $1.99 — that’s the kind of Amazon publishing deal I’m talking about. She provides the content, Amazon provides a delivery channel for cheap, they split the modest price. The one Kaling title at Amazon published by a traditional publisher is $13.99 for the Kindle version.

I bought a couple of the $1.99 published-via-Amazon e-books. That was enough. They averaged an error that any sort of copy editor would have fixed about every other page.

@Michael Cain:

Amazon Prime is not free.

In at least two facets. Money. Privacy.

Without a proper library, my education would have been severely stunted.

I did not have the means to buy the books I read.

PS-prices on university textbooks are fucking outrageous.

Amazon Prime is not free.

Fine, I’ll rephrase. If you’re already paying for an Amazon Prime membership, Amazon will not charge you additional money to read or listen to the Kaling stories online.

@Michael Cain:

Pretty big distinction between “free” and “available if you’re a paid subscriber”.

@James Joyner:

It is a weak argument, but another example of how perfidious Amazon is.

@Michael Cain: ” For example, they don’t compete with the traditional publishers for the next big book from Stephen King, with advances and editing, and layout, or organizing promotional tours. ”

That’s just flat-out wrong. Yes, they have their self-publishing arm, which is a godsend for non-fiction with a small but very specific market and a graveyard for fiction, but they also are a full-service publisher. They stole Dean Koontz away from one of the Big Guys a few years back, and I guarantee they weren’t providing lower guarantees. On a much smaller scale, one of their imprints published a series of 28 books I co-created and edited a few years back, and they were by far the best publisher I ever dealt with.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl: As opposed to Archie-porn, which is something else entirely.

An unsung hero in books for the masses is Half Price Books retail outlets.

Decently priced. Knowledgeable staff. Good browse.

@wr: Thank you. Was not aware that they had gone into the mainstream publishing business.

@de stijl: My original statement was ” For free if you’re one of the 100 million Prime members.” I consider it common knowledge that “Prime member” means you’ve paid an up front fee for a variety of services.

@de stijl:

They are. One of the contributing factors to the success of Library Genesis. And either the Russian hackers are working it, or there are a lot of people in the US who agree.

A friend published a textbook in an odd field a few years ago. Never available to the public in e-form, only hardback. A few weeks after it was released, there was a PDF of it available through Library Genesis. I helped her with the comparison: it was a bit-perfect copy of the file that was sent from the publishing house to the printer. Including 300-dpi images for the front and back cover, plus the proprietary fonts the publisher had chosen.

@Michael Cain:

Let’s be done with being pissy at one another. We both had our jabs. Enough. No need to continue. You’re cool in my book.

@Michael Cain:

In no way am I advocating authors and publishers should be ripped off on textbooks, but the market is distorted and exorbitant. $1200 on top of tuition is mafia extortion rates.

Vox has an explainer on textbook prices.

There is a reason students go to extra-legal means to obtain low-res screen shots of textbook pages, let alone the sketchy PDFs from dubious sources likely larded with malware.

The base price is stupidly high. Unaffordable for many.

@de stijl:

Absolutely. Library Genesis grew out of the obvious fact that Elsevier’s and the IEEE’s prices put technical literature out of reach for a large majority of the planet’s population. What I find most impressive is that LibGen and their partners are not providing sketchy PDFs. Someone is providing absolutely clean copies to them in clear violation of their countries’ copyright laws. Or the hackers are good enough that we ought to be terrified about any critical systems run by for-profit entities.

I have a piece of code here that I really need to open source. It’s glue code to pull together a bunch of other open source software to do thematic maps: cartograms and prism maps. I started on it — geez, nine years ago now — because the commercial map software to do that particular task was more than the household research budget could afford.

@James Joyner:

I genuinely laughed out loud at this one, because I am much more likely to be annoyed — and perceive more “societal loss” — from not being able to get my hands on The Martian or a Michael Pollan title than I am by missing out on any book by a politician. Even that politician.

@DrDaveT:

Judged by Kaling’s tv writing, I would totally read her memoir.

And I know Koontz is obvious crap. But, he writes entertaining obvious crap. The likelihood of good boy or girl dog is ~ 70%. The likelihood of a developmentally disabled youngster having savant capabilities is ~ 40%. The likelihood of an excruciatingly icky “love-making” scene is nigh 100%.

Koontz is utter crap, but I kinda adore him.

I did genuinely actually like some aspects of the Odd Thomas series, no foolin.

I miss Pirate Bay. What wonderful years they were, when we could download virtually anything for free merely by committing a technical breach of copyright law which nobody was ever going to know about. Our grandchildren will never believe us.

@Ken_L:

I would never go for that route. Never did. Never will.

@just nutha: As should be obvious from the piece, I think Amazon has an enormous amount of power and I think we should be concerned with how they wield it. If they were buying up major publishing houses and denying libraries access to their books, I would argue for trust-busting even though I no longer borrow books from libraries.

Here, though, the only thing that seems to be being withheld are digital and audio versions of a handful of books. I’m struggling to find the harm. If the argument “but poor, blind kids rely on library audiobooks” — which occurs to me might be the case — were being advanced, I’d acknowledge the harm. But self-published books by various yahoos? Exclusive deals with comedians? Meh.

The author of the piece does a terrible job advancing their argument.

The library licensing terms for e-books and downloadable audiobooks are entirely out of wack when compared to physical media — they cost a lot more and they have very onerous restrictions on how many times they can be lent out. The cost per lend for digital media is much higher.

(If you want to go off into the weeds, you can measure the storage costs of a physical book and the maintenance costs of a digital book, but lets ignore that)

The piracy argument is a red herring — until the publishers figure out how to plug the holes on the consumer side to stop piracy, there’s no reason to believe libraries are the source. And the costs of piracy are always grossly overstated anyway.

So, that leaves us with this: do we care that digital copies of works are unavailable or less available through the public libraries?

There are digital exclusives — where there is no physical copy — but this is still a relatively paltry amount when measured by what people actually read. That’s a problem that might become serious in the future, but for now… we can skip it.

Do we care that the digital version of a NY Times bestseller is much more expensive for a library to lend out than a physical copy? Or the 500th best selling book of 2012? Is it important, or just a silly flourish for well-to-do folks to put something on their phone?

I care, because I’ve hit the age where the font size on physical books is often too damn small. If I’m reading something it has to be on a screen, or be one of the very small number of “large print” books. It’s an accessibility issue.

I’m more bothered that some works aren’t offered digitally at all though — not for individual purchase or for libraries. And significant things. Milan Kundera, Graham Greene, Bohimul Hrabal… things you can find in libraries, and which Amazon has the text of (if they have the “search inside the book” feature, they have the text), and they are unavailable. I have resorted to piracy there.

@Michael Cain: ” Was not aware that they had gone into the mainstream publishing business.”

If there is any kind of business anywhere, it’s a pretty safe bet they’ve gone into it…