An Observation about American Democracy

The ongoing Republican debacle and what it says about representative democracy in the US.

There are a variety of reasons to be unhappy with the current inability of the House Republican caucus to elect a Speaker of the House, including the rather obvious fact that electing a leader is one of the most fundamental legislative tasks for the majority party to perform. Indeed, it is a massive signal of the utter dysfunction of the party that they cannot organize themselves in this most basic of ways. In a rigid two-party system it is a national necessity that both parties be able to function at minimal levels at the very least. The lack of ability to cohere around a leader is made all the worse given a looming budget crisis and two international crises that require US attention, one of which emerged whilst party leadership (I use the term advisedly) continued to demonstrate an inability to count to 217.

I am disturbed not only by the general inability of the Republican Party to perform the minimal task of party existence, but on the macro level I also know that the likely democratic feedback needed to correct this behavior is going to be less efficacious than is we, as a country, need.

By this I mean, that if we had representative and competitive elections in the US, the chance that the GOP, especially some of its more problematic members would be exposed to having, at the very least, to explain themselves to the public as to why they can’t elect a leader (I keep harping on this because it is so very basic–we aren’t talking about fixing the tax code, addressing spending bills, or anything complicated here).

Indeed, they should have to explain how in the world they a) agreed to a plan that allowed a small minority of the party to blow up the chamber in the first place, and b) decided that a guy with practically no legislative accomplishment was chosen to be Speaker of the House designate (for a dew days, anyway).

Note this from WaPo a few days ago: Jim Jordan’s remarkably thin legislative track record.

Critics of Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) have increasingly pointed to this — most notably the fact that he has yet to get a bill signed into law since being elected in 2006.

[…]

The most oft-cited data on legislative success comes from the Center for Effective Lawmaking, a joint project of Vanderbilt University and the University of Virginia.

[…]

CEL data have routinely ranked Jordan near the bottom of the House when it comes to his effectiveness. To wit:

- Last Congress, only four lawmakers ranked below him.

- He has ranked in the bottom five among House Republicans each of the past four Congresses.

- He has ranked in the bottom quarter of House Republicans in every full Congress he served in.

- Before this Congress, its data don’t record any bills Jordan sponsored passing or receiving any action — whether in committee or on the floor.

Not to harp too much on Jordan, but not only does his legislative record somewhat explain his inability to get the needed votes for Speaker from his caucus (as well as the general folly of his approach to whip those votes) but it is a damning notion that the party tried (thrice!) to make a guy who barely legislates into the Speaker of the House, a job whose core job is moving legislation.*

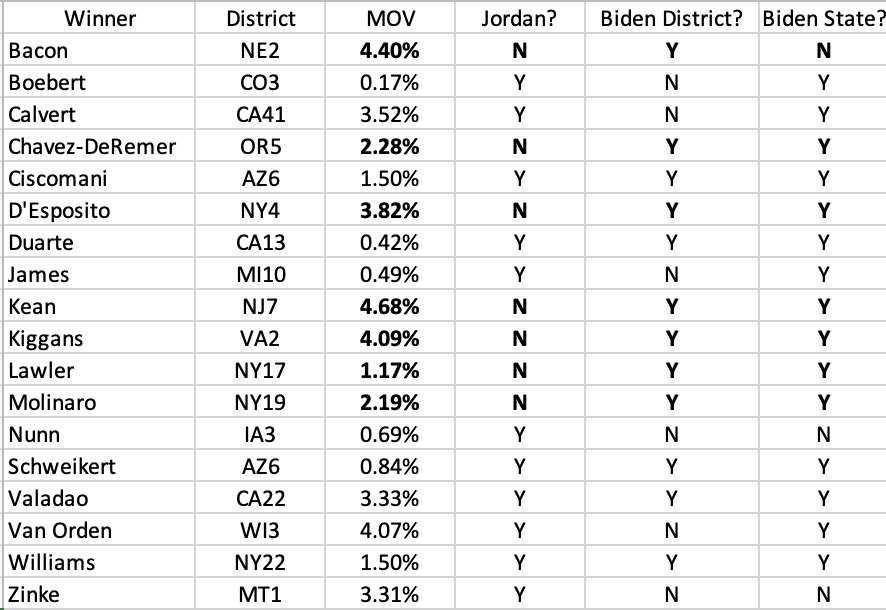

Setting aside the specifics about Jordan (who hails from a super-safe Republican district, having won re-election by almost 40 points in 2022), the problem with all of the poor behavior by the party is that, as I frequently note (for example), electoral competition in the US is anemic at best.

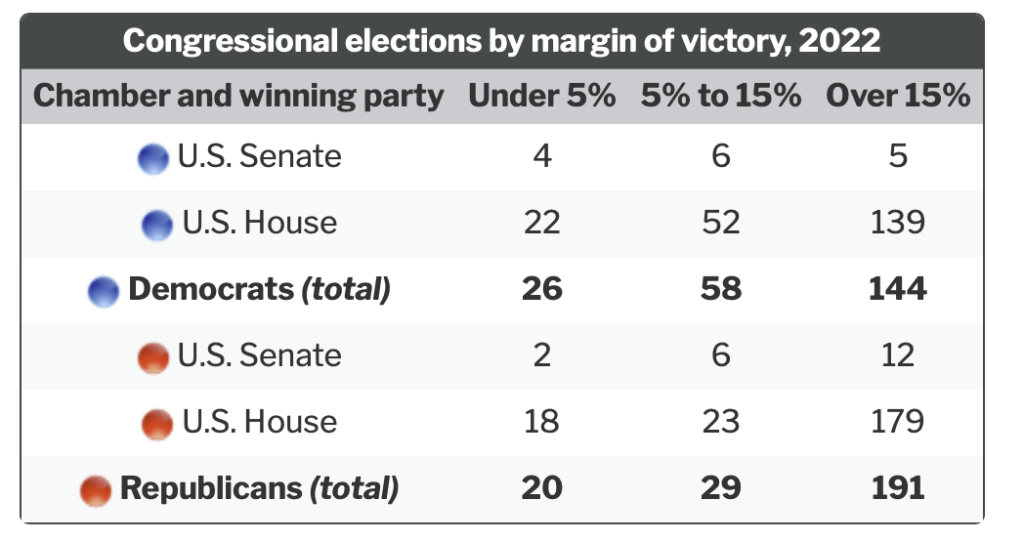

Here’s the breakdown (from Ballotpedia) of 2022.

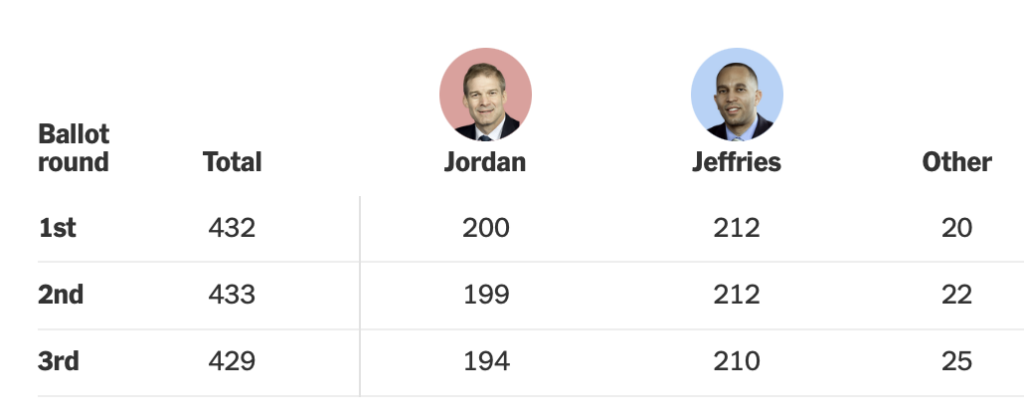

So, I don’t think it is a coincidence that the breakdown of competitive vs. noncompetitive Republican seats does look all that different from the votes for Jordan as Speaker (via the NYT).

I will note, that the correlation of competitive seats to votes against Jordan is not perfect. For example, Lauren Boebert won re-election with only 0.17% of the vote, and yet she has been a pro-Jordan vote. But, of course, she is not going to go into 2024 by trying to moderate. Her brand is what it is and so no amount of electoral competition will get her to change her tune.

But, in looking at all members of the House who won their election by five points or fewer, I would note the following when looking at Republicans. Seven of the not-for-Jordan votes (more than needed to stop Jordan’s acquisition of the speakership) were by Republican House members who won their seats by fewer than 5 percentage points. They also were from districts where Biden won in 2022 (and all but one was from a state Biden won). These are members who know that their re-election chances could very much be jeopardized by voting for a Speaker whom many/the majority of their constituents would likely view as unacceptable.

I would argue that these members, with clear electoral stakes affecting their calculations, formed the foundation for opposition to Jordan, which in turn allowed several other members of the caucus to also vote “no” knowing that he wasn’t going to win (although I do think it is possible that some of them also voted no for any number of principled and/or political reasons).** There were two additional anit-Jordan votes from Republican members who represented Biden-winning districts (Fitzpatrick from PA01 and Lakota from NY01) although they both won their seats by large margins (each almost won 12%, which might be enough to give them some level of comfort).

No doubt some of the narrow winners in my table above voted for Jordan for ideological or other reasons (perhaps they fear being primaried).

So, the good news is that we can see here some level of democratic feedback in action. The bad news, however, is that all of this is affecting individual behavior and not the party as a collective whole. While some members of the Republican caucus can see a direct link between voters and their political careers, the party as a whole is largely insulated from such feedback (again, 191 of them won their seats by 15% or more). Indeed, not only do not they fear their district’s electorates if they fear anyone it is the far smaller, and likely more radical, primary electorates in their districts. This is not a healthy democratic feedback loop.

At any rate, my overall point is that the general fear of electoral punishment for the party as a whole is low given the utter lack of competitiveness in most districts. This is owing to a combination of a too-small House, primaries, and the usage of single-seat districts to elect members (gerrymandering makes it worse, especially in some states, but it is not the main culprit).

A party that cannot perform basic functions should fear voter opprobrium, but there is nothing in our system that really would promote such correctives. Instead, we have to hope that the fortunes of a handful of members of Congress manage to send a message to the broader party. However since the system only sends signals primarily to individual members and not the collective whole, I am not sure if the right message will be sent.

And look, of course, there are plenty of Republican voters out there who are fine with the circus, not to mention a lot of voters writ large who don’t really understand the depth of stupidity/incompetence on display by House Republicans at the moment. But it is inalterably true that our overall electoral system and governing structures do not provide any way to provide electoral accountability for this mess. At a minimum, if the president had to be won by the party that got the most national votes it would be a start as it would give voters some ability to reward or punish parties who can’t get their basic act together.

But some form of proportional representation that allows for vote preferences to be truly registered in elections for the House is something we desperately need if we want real electoral accountability and parties that know they have to adapt to competition so as to win (this is key to healthy representative democracy). Further, we need a system that provides real incentives for new parties to form–especially since it is increasingly obvious that we have the basis for more than two parties. The Republican inability to coalesce around a leader demonstrates this fact pretty clearly.

* And I won’t even get into the bizarre political move (IMHO) of nominating a guy for Speaker who has been accused of ignoring sexual abuse while a wrestling coach at Ohio after having had a Speaker (Dennis Hastert) who admitted to serial sexual abuse while he was a high school wrestling coach. Not only is it, in my view, morally problematic (to put it mildly) for Jordan to be in the House, let alone in a position of leadership, but from a purely political POV, it struck me as simply dumb for the Republicans to allow part of the story of the Speaker of the House to be about molestation.

**WaPo does a pretty good job of detailing and categorizing the group of GOPers who voted against Jordan: The surprising group of Republicans who kept Jim Jordan from becoming House speaker.

Thanks for crunching the numbers on this, Steven, I’ve been looking for this.

How many other societies have a gerrymandering system like ours?

@Michael Reynolds: No prob.

@Kingdaddy: In theory, any FPTP system is gerrymandered to one degree or the other (in the sense that any single-seat district is going to be biased in some way). But because we squeeze the districts into state and because the House is far too small for our population, I think we are the main example.

I think that Hungary has some elements of this–I know that the rural districts are overrepresented.

I don’t know why Jordan’s record is regarded as a failure. He’s doing his job. Chuckles Koch ain’t paying him to pass legislation.

@ Steven

Fascism 101. Find someone who will trade blind loyalty and a willingness to employ violence to achieve political goals in exchange for being promoted to a position of power they could never, ever achieve on merit.

Maybe not the most original observation, but what we are seeing right now (IMO) in the House’s GOP caucus is the same lack of democratic accountability as in the broader political system.

The fact is that Scalise beat Jordan 113 to 99, and that this (the will of the majority) should have translated into the full House GOP caucus backing Scalise on the floor.

Except that Jordan said “IDGAF about the majority, I want to be Speaker regardless.” It’s the same thing that Trump did following the 2020 elections. And McConnell when he blocked Garland. And when people say “a republic not a democracy.” And even the very structure of the Senate and the overrepresentation of rural districts in the House.

The chickens have finally come home to roost, it seems.

No point in further argument so this just for the record: I haven’t seen any evidence that actual good governance corresponds to the ease of creating parties.

@MarkedMan:

The bottleneck isn’t so much creating new parties as giving them (meaningful) ballot access.

The US is really bad at this. This contributes to a set two-party system that is unresponsive to voter feedback.

ETA: The difficulty of gaining ballot access is perhaps the third factor (besides FPTP and weak parties) that contributes significantly to a particularly unresponsive two-party system.

@MarkedMan: That’s cool.

I just know that if there were more parties in the House there would be better pathways for a governing coalition to emerge.

So, for the record, I don’t understand how you look at this situation and think that is it as optimal a configuration as any other.

And, for the record, I have argued that more parties lead to better representation (among other things) and while I think that would lead to better governance, you are the one who always reduces to governance alone.

There are no guarantees, to be sure.

Side note: Poland may have reversed a slide into authoritarianism because it’s system does not simply reward the plurality.

@MarkedMan: why wouldn’t a democracy that created a more representative party system not be preferred?

I don’t get it.

@drj: ballot access is a problem, but it by no means the reason we don’t have more viable parties.

@drj: True. On the other hand, the “belief” in only two parties may well be so bone deep in the American collective psyche that the road to multiple parties and diverse representation could be nearly impossible to navigate. I know of no one who has suggested a path beyond “this might be a direction to go.” Sure, but how do we get there?

@MarkedMan: I’m not much of a student of history, but my crude study seems to show that good governance comes out of having leaders who serve (as opposed to merely ruling over) the people in the nation they lead. When those people serve as the electors of the leaders, the burden of concern for the ability of the candidates for service/leadership shifts to the voters. I can see that any partisan system will, therefore suffer from the same GIGO phenomena equally to the others. On the other hand, I can also see that systems that take discrete input from more sources have a better chance of finding the most workable compromises/solutions–even if only theoretically (GIGO still applying negative inputs).

(TL/DR: We have met the enemy, and he is us.)

There’s a potentially large price to be paid at the primary level for opposing Jordan. I’m wondering how many of the “yes” votes were cast knowing that he would lose, and that it was a free bit of red meat to toss to the rabid base.

How many secretly opposed Jordan, in their hearts, but saw no upside to putting it on the record, and only potential downside?

I think our system encourages change of the “gradually, and then suddenly” variety. And until that “suddenly” happens, there’s a lot of speculation that is basically reading tea leaves, and doing Kremlinology to figure out who is closest to Stalin in the photograph, and why are they wearing a hat and what that means about Poland.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Cannot believe that we a 100 years into the House Cap. What’s especially frustrating is that this is one of the few things that can be changed without the Amendment process, but neither party is interested in that.

@Steven L. Taylor:

True, I’m much more interested in good governance than representation for representation’s sake.

I don’t. I would really like to know what we can do to make better governance. But I t certainly doesn’t seem to me like there is any correlation to number of parties or ease of creating them, but I could be wrong.

I guess in the end I agree with some of the founders in that I find the fixation on parties is a negative distraction from the goal of good governance. Parties, and the sports team attitude they engender, or the extremism they can exacerbate in a multiparty system are problems to be managed. They don’t strike me as a solution to anything.

If I’m wrong, great. But as a layman I haven’t been able to find any research that connects a particular system of democratic governance to the quality of that governance.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Could you expand a little on this?

[Massive edit — I see what I was missing.]

Running as a third party candidate means certainly losing, even if getting on the ballot were easy. I agree with you that more viable active parties would solve a lot of problems, but I don’t see how to get there from here. The barriers to any attempt to create a new party are overwhelming.

More concretely: what is the minimum set of changes that you think would be needed to make it possible for there to be more than two parties represented in Congress?

@MarkedMan:

Parties are inevitable. The focus on them is out of necessity. If a proposed solution ignores their existence, that proposal can be dismissed out of hand.

@Kurtz:

Agree 100%. It’s just that I haven’t seen that having lots of them means a country, on average, has better governance.

Its a party problem but it’s just as much or more a voter problem. In a rational world the kind of aberrancy we see would get people voted out. Instead it makes them heroes with the voters in their district, especially the primary voters.

Steve

@steve: But you can’t discount the identity issue that is reinforced when there are only two teams.

@MarkedMan: Unless you want to say that the US is governed as well, or better, than most countries globally, I simply don’t understand your basic position. As I have demonstrated before, almost every other democracy in the world has more parties.

But the part of you positions that I do not understand is why you don’t think that more responsive politicians wouldn’t increase the chances of better governance

And BTW: if you think parties are inevitable, you are not subscribing to the views of the founders, who flatly did not understand parties.

@DrDaveT: The main change we need is to stop using primaries to nominate candidates because currently it is simply easier for a new politician to try and obtain one of the established labels than it is to try and build a new party.

@MarkedMan: I think part of the problem with our ongoing debate is that I cannot, as a political scientist, guarantee that X change will end up with better governance. Politics is just too complicated to make such claims. But I can with some significant confidence assert that X change has a chance of improving governance.

I think more parties, for reasons I have written about over and over, increase responsiveness, representation, and strategic possibilities. By definition, all of that increases the chances of better governance (but it does not guarantee it, because guarantees are impossible).

@Steven L. Taylor: I see Marked Man’s objection as more parties=/= (at least automatically) more responsive politicians. And I will agree on “automatically,” but also note that more parties = a greater likelihood of more responsive politicians. More parties could also yield a more responsive electorate as measured by levels of participation across all elections–local, primary, and general, but our participation in national elections seems high right now, so change might not be obvious there.

ETA: Or basically what you just said above, and I hadn’t read yet. [chagrinned emoji]

I’ll repeat what I’ve written so many times on various websites: to make an argument predicated on the assumption that Republicans want to find a way to make Congress effective is to misunderstand completely the mentality of the extremists who dominate today’s Republican Party. Far from regretting that the House “cannot perform basic functions”, the nihilists regard this as a major achievement. They are absolutely committed to the idea of burning it all down first, and worrying later about what happens afterwards.

Steven, I think the chief reason we don’t have responsiveness from politicians is Citizens United. Money in politics is the root of both the lack of competition in primaries and the lack of legislative responsiveness to the people a representative putatively serves.

What I find interesting about the Jordan debacle is why so many people thought his winning was practically inevitable before it went down in flames. Here’s an example from one of our commenters just a few days ago, following his first failure:

I get where the cynical “meh” comes from. We’ve lived through countless examples where so-called “moderates” within the GOP show no spine after pretending to do so. We also remember McCarthy attaining the Speakership after a bunch of failures.

But there were crucial differences when it came to Jordan. As mentioned, the holdouts have to worry about reelection in Biden-friendly districts. The belief that Republicans are more scared of primary challenges than being voted out in the general is true in large part because most House Republicans occupy safe, gerrymandered districts. The effect has never been as universal as some people imagine.

But what was truly remarkable about Jordan was how he did nothing to win over the holdouts. When McCarthy fought to get the nomination after several failures, he made real concessions to his holdouts. They were terrible concessions that would later come back to bite him, but making concessions of some kind is how Congress works, and has always worked. Jordan resorted to bullying and intimidation, but it was toothless bullying and intimidation. Maybe if he’d gone full fascist and literally started murdering his opponents, he’d have gotten somewhere.

I think it’s incorrect to view it as a matter of whether the holdouts showed spine; at the end of the day they were very much acting in their own self-interest, and Jordan and his allies gave them no reason to think their self-interest lay elsewhere.

@Kylopod:

Sure, why not… that is the mindset of most of the MAGA out there.

@Steven L. Taylor: @Just nutha ignint cracker: First, I am not sure what either of you mean by “responsiveness”. There are different ways to define that word in a political context. Here’s how I would define “responsiveness to voters desires”: How fast a political system enacts the will of the majority of voters.

Second, Steven, you accept that “responsiveness” is a good to be strived for, in and of itself. I suspect that there is an optimal amount of responsiveness, but “more responsive = better” is a very simplistic view of how systems of any kind work. In the physical domain, a system that is too responsive results in massive overshoots followed by undershoots and in extreme cases can lead to out of control feedback that renders the system useless at best and actively harmful at worst. I think it very likely that the same applies to political systems.

Third, the assertion that because I question whether more parties is a good in and of itself means that I think our current system is optimal or ‘the best’ is a ridiculous interpretation of what I’ve said. It’s just erecting a straw man argument around my actual words.

Fourth, I think you give way too much importance to parties as a means towards change. Party leadership and backbenchers are comprised of individuals. And more generally, government leadership are comprised of individuals. Ensuring those people are aiming at the right targets and are effective in their efforts is the most crucial thing. There are many ways to effect change and I simply don’t agree it is obvious the most effective way is to create a new party. Asserting it without proof isn’t going to change my mind, which is why I just put that original comment in “for the record”. I’m not sure what benefit we get from rehashing this argument, as I don’t think we are in any danger of changing each others minds at this point 😉

Fifth, you’ve never dealt with the concerns I’ve raised about multi-party systems. From what I can see, there are two types of parties: those that function primarily as teams in which the vast majority of members blindly cheer them on regardless of the actual governance, and much smaller special interest parties who have more focused membership but often have very harmful goals. Having 3 or 4 percent of the votes gives them a crucial tiebreaker role, allowing them to demand governance that is actively harmful to the country and to the vast majority of people. In a hypothetical world where, say, the Libertarians got four percent of the presidential vote, is there any doubt they would have cut a deal with Donald Trump in 2020?

Bottom line, I have no idea what makes the best form of democratic system in terms of outcome, in terms of governance. I’m open to the idea that messing about with parties, FPTP, ROV, etc can improve governance, and I would love to see actual research on how these things correspond to effective governance. And no, of course I don’t expect that tweaks here and there instantly transform into better government. But there are over 200 countries and there is such a thing as statistical analysis. Although I will say that when I look at the relative effectiveness of various governments and then look at the dramatically varying electoral systems the democracies have, it makes me think the importance of something like party formation vis a vis effective governance is a small factor.

@MarkedMan:

Perhaps you could understand why I find this to be a frustrating place for you to go. You argue with a lot of certainly, but then note that you really don’t know. And while I fully agree you do not have to accept a thing that I say or argue, but I am doing so from a position of multiple decades studying this stuff.

It makes for a weird dynamic.

Steve: “… it struck me as simply dumb for the Republicans to allow part of the story of the Speaker of the House to be about molestation.”

IIRC, there was a recent WaPo article which praised him. They ignored his failure to get the Speaker position, and didn’t cover his long track record in the House well.

They also pushed the sexual assault and insurrection down to the bottom.

IMHO, the GOP assuming that the ‘liberal’ MSM would cover for otherwise[1] disqualifying factors was and is a good assumption.

[1] meaning ‘disqualifying for a democratic politician’.

@MarkedMan:

See, I think I have been super clear about this. For example, when most of Congress doesn’t have to worry about re-election, that makes them unresponsive in a democratic sense. Surely I have been clear about this? And surely you understand that we (generically) should want elected politicians to be responsive to voters rather than being in a position to ignore them?

The whole point of representative democracy is that voters choose politicians to do X and if they don’t do X, then the voters have to decide that either not X was a good choice or that they should elect someone who will do X. That is basic democratic responsiveness.

We lack this in large measure in the US.

I would note that a key point in the post is that the GOP members who really have to address what their district wants rather than being able to ignore the voters are the ones that prevent Jim Jordan from being Speaker.

This strikes me a “good governance” outcome.

@MarkedMan:

No, it’s not. You constantly assert that you see no reason why more parties would be better, and that logically suggests that you think that the current two-party system is fine (or, as a minimum, no different than a multi-party system). You always push back on the notion that more parties would be an improvement. That is a weird double-down on our current system in my view.

You are pretty stubborn about theism in fact–to the point that even in a post that really isn’t about more parties directly you had to go on the record. How is this not at least a partial defense of two parties?

@Gavin:

While I think money in electoral politics is a problem, it is not in my view the main one.

MTG did not have a ton of money when she ran for the GOP nomination, certainly not a lot of PAC and outside money. But because there is no gatekeeper in American parties she was able to win the primary and then win in essentially an uncontested race. Same for Boebert and bunch of other crazies.

And right now most of the members of Congress do not need huge war chests to win reelection.

I am thoroughly convinced that the main two problems as it pertains to democratic responsiveness and accountability are:

1. Weak parties as driven mostly by primaries.

2. Most districts are utterly uncompetitive.

Declare Citizens United unconstitutional tomorrow and those conditions don’t change. Even if we one to public financing tomorrow, those things don’t change.

@Barry: Indeed. I am somewhat surprised that the allegations (and thematic connection to Hastert) seems buried.

@Steven L. Taylor: One doesn’t need to know the optimal answer in order to question any specific proposal.

You seem to be arguing from authority. I ask, what system results in most effective governance? You conflate responsiveness with effectiveness, and when I question that you respond that you have been studying this for a long time. Maybe it’s as simple as that: you feel more parties is the desired end goal because it that will increase the (as yet undefined) responsiveness, and that is the very definition of good governance. I view “responsiveness” as something to be altered in fine tuning a system. I don’t see how we can get past that without getting much more specific as to our definitions. For example, I proposed a definition of responsiveness above. Do you agree with it? If not, how would you define it.

@Steven L. Taylor: @Steven L. Taylor:

And this is why I have generally dropped out of these discussion, as you did an amazing job of ignoring what @MarkedMan: actually said. Repeating the rest of his comment following the sentence you “replied” to in your first comment, not merely none of which was actually responded to, but rather you somehow inferred the exact opposite of what he said, and responded by saying that it is axiomatically not true, rather than presenting the proof he is seeking.

“I’m open to the idea that messing about with parties, FPTP, ROV, etc can improve governance, and I would love to see actual research on how these things correspond to effective governance. And no, of course I don’t expect that tweaks here and there instantly transform into better government. But there are over 200 countries and there is such a thing as statistical analysis. Although I will say that when I look at the relative effectiveness of various governments and then look at the dramatically varying electoral systems the democracies have, it makes me think the importance of something like party formation vis a vis effective governance is a small factor.”

@Steven L. Taylor:

I do not. I concede that it could be true but have said repeatedly that I’ve seen no evidence to support it. I have looked. I will continue looking. As a layman, I don’t have the background you have and so don’t know where the research lies. But I assume somewhere a researcher has published a paper where they say, “Here is a definition of effective governance. Here is how we have ranked 220+ countries wrt the outcomes of their systems, and why. Here are the things associated with those that rank highly and here are the things associated with those that rank low.” I would be very interested in that and if there was a positive association with ease of party formation it would definitely change my thinking.

There are all kinds of hypotheses in the world. Asking for evidence in support of one is not the same as saying that I think it is wrong. You have repeatedly said that it is self evident and all I’ve done is given reasons why I don’t think it is self evident, at least to me. In any case, actual research, well done, would go a long way to settling the question.

@Steven L. Taylor:

FWIW, I think there is good evidence for this. The inability of party officials to have even moderate control over who their candidates are, coupled with the fact that something like 70-80% of the voters blindly vote for the “home team” (something you have supplied copious evidence for and explained very well, and has influenced the way I viewed our politics), makes it virtually impossible for a party to present a coherent platform and stick to it.

@Moosebreath: Thanks for that. Sometimes in this discussion I feel like I’m going crazy and maybe just ignoring the parts where Steven is responding to what I’ve actually said. I truly didn’t mean to restart the debate, but just wanted to point out that the “more parties are better” argument remains unproven, at least in the context of OTB. If Steven hadn’t responded I wouldn’t have added anything more. It’s his blog!

@Steven L. Taylor:

The question becomes what practical and achievable reforms can mitigate these factors (at the US federal level).

After reading I am fairly convinced of the diagnosis, however the frustrating open point is an academic blue-skying. Abstract preference for say Multi-party (which living in such systems I can not say that @MarkedMan is wrong as such on factors, the specific mechanisms parliamentary power balancing as well as political culture being I should think fundamental to whether parliamentary wrangling ends up being a positive compromise mechanism or ends up in Weimeresque paralysis and decredibilisation.

So rather than arguing over academic theoreticals that have zéro chance of occuring inside of the US system (barring some kind of major crisis and system refont), I would think that it is most useful to identify step-wise reforms that could be actionable within current system.

As, for example a question if it is practicable (practicable as in an actionable real world approach) to reform the primary system (which would seem to resolve either to less ‘democratic’ primaries with greater party élite control or non party completely open, if I have followed the prior exchanges).

Otherwise this all resolves to entirely impractical theoretical exchanges or the perhaps emotionally satisfying and perhaps quite merited but otherwise equally useless casting aspersion on the opposition party and all its members and sympathisers.

@MarkedMan:

No problem. I have sometimes felt the same.

@MarkedMan:

I am not saying “I am an authority, so I am correct.” But I am noting that this is legitimately an area of expertise for me. If this was a medical blog and I was telling you why I thought vaccines were better than ivermectin, would it be arguing from authority if I noted that I had been a medical doctor for thirty years?

@Moosebreath: The thing is, while I will admit that I have not produced a study that functions exactly the way MM wants, I have written thousands of words and, moreover, spend a lot of time in a good faith effort to discuss.

I am sure that I do not answer every single point. I have neither the energy nor time to do that.

I did realize (and noted in a new post) that I have already written a very lengthy multi-post discourse on the number of parties in a comparative perspective.

@Lounsbury: The argument about practicality does not change the fundamental analysis.

I truly believe that until a critical mass of people understand the true underlying issues that there will be no change.

I have written about this as well.

@MarkedMan:

Because it is literally sitting on my desk to my left as I type, Lijphart’s Pattern of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries, 2nd edition kind of does that, although not just for the number of parties (which is really not a singular variable, as I have tried to note, because I am arguing for the conditions that lead to multiple parties, not just more parties). Chapters 15 and 16 kind of fit what you asking for.

@Steven L. Taylor: I will endeavor to find more examples.

Again, as I have noted before, chapter ten of A Different Democracy does discuss policy outcomes in differing countries and the US does not rank as well as other, differently configured democracies.

@Steven L. Taylor:

One can gather from the responses including my own that contra the structure analysis/ argument you have been rather less successful in conveying clearly this part for the reasonable commentators. Or perhaps neglect in favour of the structural althoughthatvpiint seems to have successfully made. I have gathered by recollection that the Primaries are a particular reform area

@Steven L. Taylor:

If this was a medical blog and someone said, “it seems there are good reasons to think ivermectin might be beneficial (BTW, there are, but they didn’t pan out) and I haven’t been able to find any research on it”, it would be helpful if you referenced, say, the FDA recommendations on ivermectin or the Cleveland Clinics page on vaccine safety and efficacy.

That said, and reading your replies further down, I see you recommend chapter 10 in A Different Democracy. You have recommended this several times before and I purchased it, but if you pointed to chapter 10 specifically I missed it, and must admit I gave up when the first several chapters seemed to presume what I was looking for evidence for. I will, of course, now read chapter 10, and anything else in there you think touches on this discussion. And I just purchased Patterns of Democracy and will give that a go too. Thank you.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Thank you for your responses @Here and @Here. I will resume not commenting on these posts.