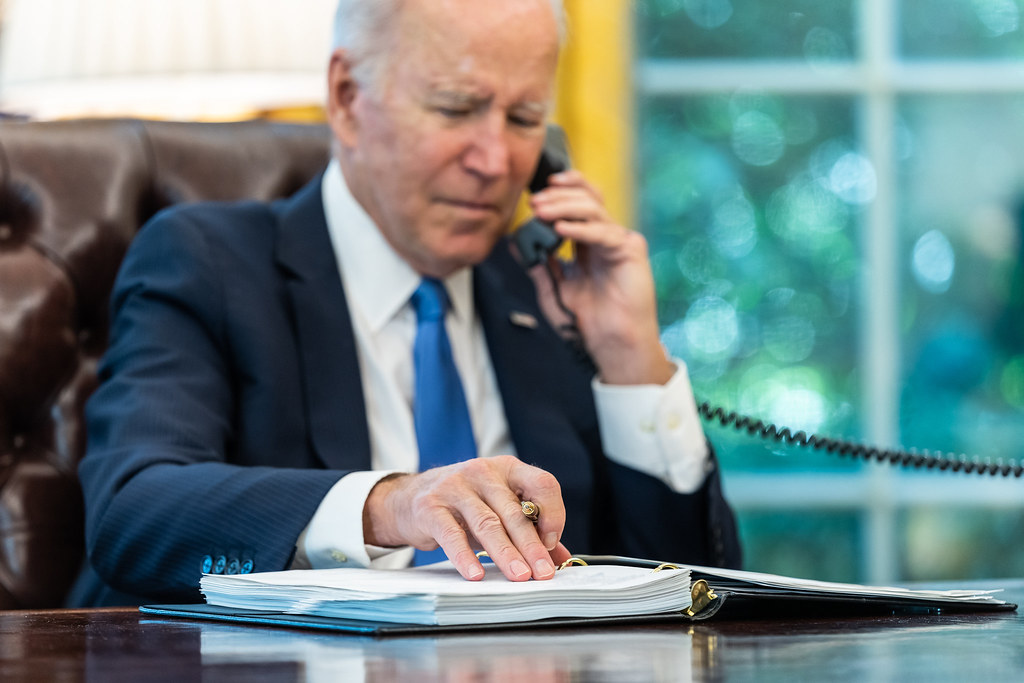

Biden Continuing Trump Foreign Policy?

Normalcy is not a bad thing.

A piece in today’s NYT from diplomatic correspondent Edward Wong headlined “On U.S. Foreign Policy, the New Boss Acts a Lot Like the Old One” treats the normal operation of the US government as though it were an anomaly.

A fist bump and meeting with the crown prince of Saudi Arabia. Tariffs and export controls on China. Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. American troops out of Afghanistan.

More than a year and a half into the tenure of President Biden, his administration’s approach to strategic priorities is surprisingly consistent with the policies of the Trump administration, former officials and analysts say.

Well, yeah. While Trump is far and away the most erratic and unorthodox American President in my lifetime, he was nonetheless the American President, sitting atop a massive diplomatic and national security apparatus that runs our day-to-day foreign policy. Further, as President Obama liked to say, the presidency is like a relay race, in which one runner takes the baton from another and keeps running the race.

Saudi Arabia has been an uncomfortable US ally for generations. We have been ratcheting up our competition with China since the turn of the millennium and, certainly, since Obama’s “pivot to Asia” in 2011. Biden would almost certainly not have moved the US embassy in Israel to Jerusalem but he sure as hell can’t unmove it. And, even if Biden wanted to keep US troops in Afghanistan—which he didn’t—that die had already been cast by his predecessor.

Wong demonstrates the key ways in which Biden has put his own stamp on our diplomacy:

Mr. Biden vowed on the campaign trail to break from the paths taken by the previous administration, and in some ways on foreign policy he has done that. He has repaired alliances, particularly in Western Europe, that Donald J. Trump had weakened with his “America First” proclamations and criticisms of other nations. In recent months, Mr. Biden’s efforts positioned Washington to lead a coalition imposing sanctions against Russia during the war in Ukraine.

And Mr. Biden has denounced autocracies, promoted the importance of democracy and called for global cooperation on issues that include climate change and the coronavirus pandemic.

Those are important things! It’s a return to normalcy. And, with the exception of some counterproductive public swaggering by subordinates, Biden’s response to the Ukraine crisis has been simply masterful: simultaneously bolstering the Western alliance, weakening and humiliating Putin, and avoiding escalation.

But in critical areas, the Biden administration has not made substantial breaks, showing how difficult it is in Washington to chart new courses on foreign policy.

That was underscored this month when Mr. Biden traveled to Israel and Saudi Arabia, a trip partly aimed at strengthening the closer ties among those states that Trump officials had promoted under the so-called Abraham Accords.

In Saudi Arabia, Mr. Biden met with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman despite his earlier vow to make the nation a “pariah” for human rights violations, notably the murder of a Washington Post writer in 2018. U.S. intelligence agencies concluded that the prince ordered the brutal killing. Behind the scenes, the United States still provides important support for the Saudi military in the Yemen war despite Mr. Biden’s earlier pledge to end that aid because of Saudi airstrikes that killed civilians.

“The policies are converging,” said Stephen E. Biegun, deputy secretary of state in the Trump administration and a National Security Council official under President George W. Bush. “Continuity is the norm, even between presidents as different as Trump and Biden.”

“As time has gone on, Biden has not lived up to a lot of his campaign promises, and he has stuck with the status quo on the Middle East and on Asia,” said Emma Ashford, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

As noted previously, I would have preferred that Biden avoid the fist bump. But there’s only so much leverage that we have on the Khashoggi matter. I am frustrated that Biden has continued backing the kingdom’s brutal war in Yemen. My strong suspicion, however, is that President Biden knows something that I and Candidate Biden did not.

The bottom line, though, is that, once they’re in the big chair, Presidents tend to walk away from moralistic stances on foreign affairs issues they took from the responsibility-free zone that is the campaign trail.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have had to grapple with the question of how to maintain America’s global dominance at a time when it appears in decline. China has ascended as a counterweight, and Russia has become bolder.

The Trump administration’s national security strategy formally reoriented foreign policy toward “great power competition” with China and Russia and away from prioritizing terrorist groups and other nonstate actors. The Biden administration has continued that drive, in part because of events like the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The Biden White House has delayed the release of its own national security strategy, which had been expected early this year. Officials are rewriting it because of the Ukraine war. The final document is still expected to emphasize competition among powerful nations.

Mr. Biden has said that China is the greatest competitor of the United States — an assertion that Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken reiterated in a recent speech — while Russia is the biggest threat to American security and alliances.

China’s rather rapid rise over the last 30 years and increasing assertiveness, if not outright belligerence over the last 20 are simply facts that had to be considered in the crafting of American foreign policy. The personal styles and preferences of the occupant of the White House matters considerably at the margins but the world situation is the world situation and the strategic competitor, to paraphrase an old saying, gets a vote.

Some scholars say the tradition of continuity between administrations is a product of the conventional ideas and groupthink arising from the bipartisan foreign policy establishment in Washington, which Ben Rhodes, a deputy national security adviser to President Barack Obama, derisively called “the Blob.”

But others argue that outside circumstances — including the behavior of foreign governments, the sentiments of American voters and the influence of corporations — leave U.S. leaders with a narrow band of choices.

“There’s a lot of gravitational pull that brings the policies to the same place,” Mr. Biegun said. “It’s still the same issues. It’s still the same world. We still have largely the same tools with which to influence others to get to the same outcomes, and it’s still the same America.”

Among many other things, the so-called Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 required the President to submit a National Security Strategy to Congress on an annual basis. Over time, the frequency has reduced, such that we now get one per presidential term (which is a reasonable interval). That period spans the closing years of the Cold War, a long period of relative unipolarity and peace, the Global War on Terror, and the return of great power competition (which many argue never really left). But there’s nonetheless a remarkable continuity in that our macro-level interests—security of the homeland, economic prosperity, and a stable world order—have been constant.

Rhodes’ frustrations with “the Blob” notwithstanding, we don’t live in a world where the President can just wish the circumstances he would prefer and the world magically changes to meet his desires.

Could we get tougher with Middle Eastern despots like Mohammed bin Salman? Sure. It would almost certainly make us feel better about ourselves. But they would then be much more likely to sidle up with Russia and China. Professional diplomats are stuck with hard choices and, quite often, they will counsel sacrificing tertiary interests in order to make progress toward achieving vital ones.

Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden have advocated a smaller U.S. military presence in conflict regions. But both hit limits to that thinking. Mr. Biden has sent more American troops to Europe since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and to Somalia, reversing a Trump-era withdrawal. U.S. troops remain in Iraq and Syria.

“There’s deep skepticism of the war on terror by senior members of the Biden administration,” said Brian Finucane, a senior adviser at International Crisis Group who worked on military issues as a lawyer at the State Department. “Nevertheless they’re not willing yet to undertake broad structural reform to dial back the war.”

Mr. Finucane said reform would include repealing the 2001 war authorization that Congress gave the executive branch after the attacks of Sept. 11.

“Even if the Biden administration doesn’t take affirmative steps to further stretch the scope of the 2001 A.U.M.F., as long as it remains on the books, it can be used by future administrations,” he said, referring to the authorization. “And other officials can extend the war on terror.”

This strikes me as a silly criticism.

The Russian escalation in Ukraine was both a humanitarian crisis and an opportunity to achieve our national security interests. The March National Defense Strategy correctly identifies Russia as “an acute threat,” continuing the Trump NDS’ policy of ranking Russia as secondary to China in terms of long-term risk to US security interests but ahead of the rogue states (Iran and North Korea) and violent extremist organizations. All recent security and defense strategies have stressed the importance of allies and partners.

So, again, Russia’s invasion created a demand signal for American action that had not previously been anticipated. Biden stepped up and has bolstered the NATO alliance, convincing long-recalcitrant members like Germany to massively increase their defense spending and getting Sweden and Finland to sign on. Meanwhile, Russia is being humiliated and suffering tremendous losses.

Symbolically, I would like to see the GWOT AUMF repealed. Realistically, though, presidents are loathe to give up power. Further, GWOT is all but over except on the margins. We no longer have massive troop deployments in support of it.

On the most pressing Middle East issue — Iran and its nuclear program — Mr. Biden has taken a different tack than Mr. Trump. The administration has been negotiating with Tehran a return to an Obama-era nuclear agreement that Mr. Trump dismantled, which led to Iran’s accelerating its uranium enrichment. But the talks have hit an impasse. And Mr. Biden has said he would stick with one of Mr. Trump’s major actions against the Iranian military, the designation of its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a terrorist organization, despite that being an obstacle to a new agreement.

Trump truly screwed the pooch on this one and Biden is trying to unscrew it. That’s no easy task.

ds out as the most vivid example of continuity between the two administrations. The State Department has kept a Trump-era genocide designation on China for its repression of Uyghur Muslims. Biden officials have continued to send U.S. naval ships through the Taiwan Strait and shape weapons sales to Taiwan to try to deter a potential invasion by China.

Most controversially, Mr. Biden has kept Trump-era tariffs on China, despite the fact that some economists and several top U.S. officials, including Treasury

It does, indeed, seem counterproductive. China is an increasingly belligerent force and it makes sense to decouple our economies. The decades-long hope that we could trade our way to them becoming more open and democratic has proven empty. But it’s not clear what we’re achieving.

Mr. Biden and his political aides are keenly aware of the rising anti-free-trade sentiment in the United States that Mr. Trump capitalized on to marshal votes. That awareness has led Mr. Biden to shy away from trying to re-enter the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade agreement among 12 Pacific Rim nations that Mr. Obama helped organize to strengthen economic competition against China but that Mr. Trump and progressive Democrats rejected.

Analysts say Washington needs to offer Asian nations better trade agreements and market access with the United States if it wants to counter China’s economic influence.

“Neither the Trump nor Biden administrations have had a trade and economic policy that the Asian friends of the U.S. have been pleading for to help reduce their reliance on China,” said Kori Schake, the director of foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. “Both Biden and Trump administrations are to some extent over-militarizing the China problem because they can’t figure out the economic piece.”

Kori, as is her wont, is exactly right. But the politics are the politics. TPP was a no-brainer but, by the time the 2016 campaign got into full swing, Hillary Clinton—who had helped negotiate the agreement—had backed away from it. So, no matter who won that election, it was likely not going to be implemented. (And that’s to say nothing of almost certain rejection in the Senate.)

It is in Europe that Mr. Biden has set himself apart from Mr. Trump. The Trump administration was at times contradictory on Europe and Russia: While Mr. Trump praised President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia, criticized the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and withheld military aid to Ukraine for domestic political gain, some officials under him worked in the opposite direction. By contrast, Mr. Biden and his aides have uniformly reaffirmed the importance of trans-Atlantic alliances, which has helped them coordinate sanctions and weapons shipments to oppose Russia in Ukraine.

Again, this is a massive difference! Going from being a Russian stooge trying to shake down Ukraine to spending billions backing Ukraine’s play, to devastating effect on Russia’s military, is a complete 180.

“There’s no question in my mind that words and politics matter,” said Alina Polyakova, president of the Center for European Policy Analysis. “If allies don’t trust the U.S. will uphold Article 5 of NATO and come to an ally’s defense, it doesn’t matter how much you invest.”

Ultimately the biggest contrast between the presidents, and perhaps the aspect most closely watched by America’s allies and adversaries, lies in their views on democracy. Mr. Trump complimented autocrats and broke with democratic traditions well before the insurrection in Washington on Jan. 6, 2021, that congressional investigators argue he organized. Mr. Biden has placed promotion of democracy at the ideological center of his foreign policy, and in December he welcomed officials from more than 100 countries to a “summit for democracy.”

“American democracy is the magnetic soft power of the United States,” Ms. Schake said. “We are different and better than the forces we are contesting against in the international order.”

It stands to reason that Biden, who supports democracy at home, is more supportive of it abroad than Trump.

Biden and Trump could not be more different as leaders. Biden is a normal President whereas Trump was an aberration from all that went before. That even Trump was frequently constrained to act according to America’s interests is a testament to the strength of our institutions. That Biden is hamstrung in his ability to prioritize human rights in all instances is, at worst, a sad reality. It is not, however, evidence that he’s just like Trump.

As an undergrad taking international politics courses, the concept of continuity and change was beaten into our overhung, heads. Events that cause a major shift in a countries FP, typically are unanticipated and forced on the country from the outside. So it is no wonder that parts of Biden’s FP resembles TFG’s.

TFG was different than most prez in that he cares little for ‘normal’ procedure, so he did smash the furniture, some of which there was broad agreement that needed breaking, i.e. Afghanistan. But at the end of the day, our power to shape the world to our liking, is limited to our ability to influence and cajole, all the rest is campaign trail blather.

Great analysis James. I have to say my two greatest frustrations with Biden’s foreign policy to date are out continued tacit support of KSA’s immoral war in Yemen and the surprisingly (though sadly not unexpected) hawkish approach to Iran. I had hoped the nuclear deal would have been salvaged by now, but it just doesn’t appear to be a priority for the administration (or rather they just can’t seem to figure out a way for the US to put the deal back in place and save face at the same time).

@Matt Bernius:

I suspect Jared’s Abraham Accord lowered the priority on the Iran deal because we now have a much better (if I may go all mil-speak) kinetic solution available: Israeli Jets + Emirati (and shhh Saudi) airfields.

@Michael Reynolds:

On a related note, Saudi Arabia recently opened up its airspace to all commercial traffic. This means El Al, and other Israeli airlines, can now traverse Saudi airspace on any route that requires it, and that all airlines traveling to Israel can do so as well.

Prior to this, Air India was the only one granted overfly rights en-route to Israel. Israeli airlines were allowed only on flights to and from the UAE and Bahrain.

This would make a flight or six of IAF F-15s and F-35s, not to mention drones, a bit less conspicuous.

@Kathy:

I worry that the Iranians are not reading the handwriting on the wall. I wonder if they’ve bought into the various voices pooh-poohing the idea that we can take out their nuclear facilities. That would be very stupid. Saddam thought we couldn’t hit his bunkers, and before Iraq 2 we couldn’t. And then we could. The USAF is very good at blowing up static targets and if we don’t want to do it ourselves, I expect we can enhance Israeli and Saudi capabilities pretty quickly.

@Michael Reynolds:

The Iranians ought to be more concerned about Israel than America.

Israel took out Saddam’s big reactor at Osirak, and a nuclear site in Syria. The impressive part is each took only one strike.

and I seem to recall something about a virus and other types of sabotage at Iranian facilities.