Democracy and Institutional Design I: A Basic Preface on Regime Type

The first in an occasional series.

I have long intended to write a series of posts about representative democracy and institutional design, but life being what it is means that time to do said writing often does not materialize. Still, I have wanted to have some posts to point back to when certain topics emerge to help better explain what I am trying to get at in a given post/comment thread. Recent discussions of gerrymandering (here and here) and political party behavior (here , here, and here) reminded me of this need. Certainly these are topics I have written about at length here over the years, but I want to be more deliberate and focused. And, hence, a series is born–hopefully I will be able to progress through it with some reasonable speed.

I have long intended to write a series of posts about representative democracy and institutional design, but life being what it is means that time to do said writing often does not materialize. Still, I have wanted to have some posts to point back to when certain topics emerge to help better explain what I am trying to get at in a given post/comment thread. Recent discussions of gerrymandering (here and here) and political party behavior (here , here, and here) reminded me of this need. Certainly these are topics I have written about at length here over the years, but I want to be more deliberate and focused. And, hence, a series is born–hopefully I will be able to progress through it with some reasonable speed.

I. A General Preface on Government

How do we manage human beings living and interacting together on daily basis? How do we manage their social and economic interactions? Raw power? Religion? Hoping for the best? I know that some will prefer anarchy (no state) or minarchy (a minimal state) as the way to go and that absent government, human being still form society (see, e.g., Thomas Paine). I am not going to try and deal with notions of anarchism, if anything because I think that functional anarchy is a utopian concept (whether it be the libertarian or Marxian versions). Note that the literal translation of “utopia” is “no place” because, well, it doesn’t exist. I think that government is inevitable (and necessary).

Madison correctly noted (in my view) in Federalist 51: ” If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

Human beings are not self-regulating, altruistic beings who never act out of mischief or self-interest (or who will self-regulate those interests). Humans, rather, have interests, needs, and desires that are often in conflict with others and therefore need management. Further, these conflicting interests do not have an obvious moral hierarchy–so how do we deal with conflicting claims of power and interest? Hence, the government needs to control the governed because, ultimately, human interaction requires rules. These rules need to be made and enforced as well as adjudicated when disputes emerge. I think it is not unfair to say that human history bears this out: there is no example of sustained human community sans structured rules (i.e., government) in the annals of the Earth. If government is a necessity (and it certainly is a reality), the question should be: what is the best kind of government for humans to pursue. The problem, of course, it what that control looks like (which leads us to question about regime type). In short, it is the age-old question of “who governs?”

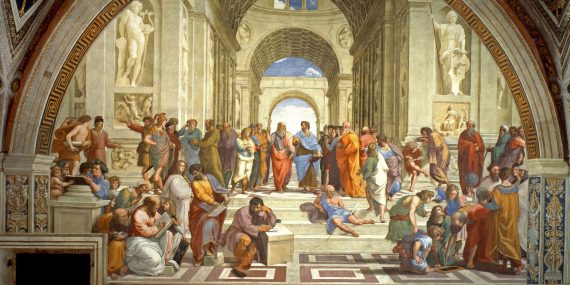

If we look back to the ancients, there was a debate over whether the one, the few, or the many should rule. Both Plato and Aristotle thought that the truly best form of government was some sort of monarchy, but with the assumption that the king would have to be wise and virtuous. On one level, they had a point: government by one person who knew what was right and just would be a pretty good kind of government–it is certainly more efficient than involving other people. The problem is, finding such a person is hard (if not impossible), and there is no guarantee that their progeny will be similarly wise. Plato came up with a complex eugenics program to produce a class of philosopher-kings and Aristotle acknowledged that there was a more practical solution which gave power to the middle class and balanced off the appetites of the rich and poor (which he called “polity” or “the constitutional regime” and really has no direct analog to contemporary politics–but that is a major digression I am not going to pursue). Both thinkers saw degeneration of superior regime types (in terms of their level of virtue) to be a possible, if not a likely, outcome of long-term operation.

Without trying to parse out the five regime types that Plato defines in The Republic and the six that Aristotle details in The Politics, the one/few/many distinction is useful. Finding the one wise and virtuous king is hard to do, as such beings are more gods than men (but that didn’t stop humans from trying this route for many centuries), and even an aristocracy made up of a superior few is not all it is cracked up to be. Indeed, once we (broadly defined) realized that the bloodlines of king and aristocrats were no different than those of the peasant, we started to figure out that rule by the one or few was not as virtuous as they were cracked up to be and hence started to sort out how to make rule by the many work.

If we skip to modern political theory, we can pretty much carve regimes into two broad categories: democratic and authoritarian. Democratic governments are (in simple terms) those which derive their power and legitimacy from the population in such a way that allows regular and significant input from the population about who governs. This takes the form of either republics (where popular sovereignty derives directly from the people) or constitutional monarchies wherein their may still be a hereditary figurehead, but where the government is selected by the population through the vote. These are all representative democracies (none are direct democracies, as such things cannot exist on the scale of a nation-state). Yes, this all touches on the false dichotomy that many raise in the US, i.e., the infamous “we have a republic and not a democracy” routine that I have written about numerous times, such as here, here, and here (and that I will likely further address in the next part of the series).

Keep in mind that while the word “democracy” is from the ancient Greek and that all the textbooks one reads talks about “Athenian democracy,” the reality is that “democracy” as we understand it is a relatively recent phenomenon that started at the national scale with, arguably, the United States, and really did not come into any reasonable form of existence until the mid-nineteenth century.* This is representative democracy of the modern type and the exact mechanics of a given democracy will vary, and that is something to get into later. A key feature of this regime type is some manner of taking into account the policy preferences of the population while also managing to protect political minorities in regards to some agreed upon set of basic rights. There is no such thing as a democracy that is simply rule by a bare majority (despite the caricatures one may encounter in some corners of the intertubes).

Authoritarian regimes are those that constrain power to likely some version of the few (e.g., the Communist Party in the USSR and the PRC, the clerical class in Iran, the military in Egypt, the royal family in Saudi Arabia and so forth).** We find that these regimes, for obvious reasons, tend to do a poor job of not only representing majority preferences in policy, but also trample minority and individual rights. As such, I will confess to a normative preference for democratic regimes, imperfect though they certainly are (being human constructs and all).

So, the purpose of this preface (which grew in the writing) is to note that there once we decide we are going to have a government (a decision that I think is inevitable) then a question immediately arises as to where power will be located. If we decide that power should be shared by the many, this takes us to discussing what democratic governance is and how it might work in its various iterations.

So, next up (as time permits), Part II: A Basic Definition of Democracy.

—-

* A really good source for a quick and easy read on this topic is Robert Dahl’s On Democracy.

**One of the best recent books on the general phenomenon of authoritarian regimes that I can think of it Milan W. Svolick’s The Politics of Authoritarian Rule (although it is not as accessible as the Dahl recommendation).

Thank you for taking on this project. I confess to having purchased your book some time ago, but not having actually tackled it yet. I am still looking forward to doing so, but am happy to have this primer as well as the discussions that will come from these posts. Political science is one of the departments that I regret having spent so little time exploring as an undergrad.

Thank you for this, Steven. I am looking forward to future installments.

I look forward to seeing the other entries in this series. Thank you, Steven.

Regarding this:

I’m curious as to how you would classify the Old Swiss Confederation. I believe it fits the definition of a democracy and goes back nearly a millennium.

I’m also interested in how you’d classify the U. S. today. Or Iraqi Kurdistan for that matter. When hereditary chieftains are routinely elected, is it really a democracy?

Off topic, but topical, NYT reports that Manafort and an associate, Rick Gates, have been told to surrender. Nothing on charges, but money laundering and failure to disclose lobbying would seem front and center.

Hopefully the first of a long perp walk parade.

On topic, I look forward to the rest of this series. Should be interesting.

I second what everyone else says. Sometimes it’s good to either refresh or (more in my case) start from first principles.

Even states that would be placed in the democratic side of the ledger are highly authoritarian. Capitalist institutions, whether government agencies or private corporations, are tyrannies in which the employees have no say whatsoever and are required to submit themselves and their rights to “the boss.”

A very small group of people decide for everyone else what is produced, how it is produced, how much is produced and where investment is made. The modern notion of democracy as a solely political phenomenon isn’t nearly expansive enough.

@Dave Schuler: It isn’t democracy unless the people who live within it have a say over the things that affect their lives. So even representative democracy is only marginally democratic.

@Ben Wolf: @Ben Wolf: I understand the argument you are making. However, I suspect you are going to disagree with most of the rest of this series.

I will try to address what you are saying in the next section.

In the time of citystates, perhaps. But the modern state is too complex to be run by a single person. Even if we had a benevolent autocrat, the resulting government would be a failure because they’d be incapable of assimilating the information needed to make decisions quickly enough.

@Ben Wolf: @Ben Wolf: My own feeling is that on the one/few/many scale, in practice the best you get is few. The best democracy can accomplish is to make those few at least partially take into account the needs and desires of the many. That said, Dr. Taylor said,

and I’ll be happy to discuss further within standard definitions of “democracy”

@Stormy Dragon: I’d allow a bureaucracy and still call it one man rule. I don’t think even the Greeks expected the guy to police the streets and haul out the trash himself.

@Stormy Dragon: Hence the “deep state”? 🙂

@Stormy Dragon:

Not that I am defending rule by the one, but even a complex state could have a rule-making body of one fused with executive power. And if that person were extremely smart and wise, and therefore would make the right decisions all the time, that would trump a legislature, etc. and the messiness of rule by the many.

(If you want to be extreme about it to make a point: if God was in charge, He would make the right choices–and I suggest that as a thought experiment, not a commentary on religion).

The point is, of course, this is impossible to accomplish, because no one is that smart and wise.

Not all hard power is authoritarianism. Just the police power.

@Dave Schuler: Authoritarianism is, ultimately, the idea that the many should be made to submit to the few. This is also the definition of liberty we see on the right: the right to submit and to be submitted without choice. The basic assumption being made, that the current system is the best we can do and just needs some reforms, are largely without merit.

Capitalism is not a natural system. It is a construct which has required centuries of experimentation, a massive government footprint and mass suffering not only to institute but to sustain and enforce. Laws and police power characterize the control employers exercise over their employees, over the profits, over the control of wealth. And because the relationships characterizing the process of production are at the foundation of our social organization, we would be foolish not to question whether this is an arrangement worth keeping.

@Ben Wolf:

No. It’s strongman government. The distinction between economic power and the police power is an important one and one that should not be conflated.

I hope this is an issue that Steven addresses in his series.

When it comes to government, sometimes it is difficult to separate out the moral ideal from the practical reality. So the way I tend to look at governmental systems is that #1, they must be capable of existing. A surprising number of strongly championed models fail this basic test. The early adherents of Marx’s Communist theories thought it was inevitable, yet reality has shown it never existed. (States call themselves Communist but these bear no relation to what Marx proposed.) Pure Libertarianism has never seen the light of day. Put another way, we tend to think of our forms of government as something we chose. But I suspect that we can only chose within very narrow constraints, given the conditions and other states that exist surrounding us.

The best form of government depends heavily on the circumstances. Early in human history, hunter gatherers could have relatively small, self contained social structures, but farming brought about the increase in value of specific pieces of land and ended the ability to just walk away from a fight. A Swiss Canton might have been able to organize a defense against another Swiss Canton, but if the army comparable to even a moderate Italian city-state decided to seize their land, they would collapse. And conversely, a Swiss Canton could not have sustained the standing army and infrastructure required by a city-state. Attempting to do so would have resulted in starvation and collapse. So, once farming exists, hunter gatherer is no longer a viable society. Sooner or later they will come into the crosshairs of the type of society capable of and beneficial to a farming community, one much more complex and specialized. Same for city-state vs. small town. (I heartily recommend Gwynn Dyer’s “War” if it is still in print.) And once industrialized societies existed, purely farming societies would eventually give way. Japan was able to stay feudal for a couple of extra centuries by literally barring all contact with the outside world, but once shipping technology increased to a certain level and Japan was seen as just another big island along the trade route rather than a mythical land at the end of the world, pressure from the more advanced states made that impossible.

So today we have extremely complex, extremely specialized social structures. Even small states increasingly find themselves aligning, voluntarily or by force, with larger structures (the EU, or the SSR’s), or collapsing.

Given these extremely large states, we have to ask: does democracy equal success and stability? While there seems to be a statistical relationship between successful countries and democracy, I would argue that it doesn’t seem to be causal. It seems to me that there are really three items that indicate success, and democracy isn’t necessary for any of them:

1) Rule of Law – meaning that what a citizen or business entity needs to do is made clear and when they do it they will not be harassed by the state

2) Low incidence of corruption – and by corruption I mean success is withheld until arbitrary and unpredictable payments or alliances are extorted

3) A non-violent and predictable method to change one ruling faction for another, at reasonable intervals (I would guess no more than 7 years, i.e. the length of time that a 25 year old might invest in lawful attempts to seize power rather than resort to violent revolution.)

@Ben Wolf:

Good point. So many people do seem to think free enterprise capitalism is some sort of god given default condition when it is, in fact, a creation of government, and requires a great deal of maintenance and support from government, as well as regulation. I suspect they also think capitalism is in the Constitution.

Capitalism is also not synonymous with, or necessary to, democracy; or vice versa.