Design Matters

UK 2024 edition.

In a Reuters report about the power transition in the UK, this passage struck me:

Despite Starmer’s convincing victory, polls suggested there was little enthusiasm for Starmer or his party. Thanks to the quirk of Britain’s first-past-the-post system and a low turnout, Labour’s triumph was achieved with fewer votes than it secured in 2017 and 2019 – the latter its worst result in terms of seats won for 84 years.

An Economist report (“How shallow was Labour’s victory in the British election?“) provides more insight:

The labour party, led by Sir Keir Starmer, scored a resounding victory in Britain’s general election on July 4th. Its majority is the largest won by any government since 1997. The party flipped seats in all corners of Britain, defeating Conservative candidates in constituencies that had been blue since the 19th century.

Yet this was not a popular triumph. In absolute numbers, the party attracted fewer ballots than it did under Jeremy Corbyn in 2019. Labour’s share of the vote, at 34%, is the lowest level for a governing party since at least the first world war (see chart 1). Instead of inspiring the masses, Sir Keir spearheaded a fearsomely efficient election-winning machine: it won 42 seats in Parliament for every 1m ballots cast, higher than any other major party in the past century. As a result, some argue that this was a shallow victory, even a hollow one. That goes too far.

It is true that Labour’s victory was as much the Conservatives’ defeat. The Conservative vote collapsed by 20 percentage points, the largest decline by any governing party in British political history. Voters abandoned the party in all directions—not just for Labour but for the Liberal Democrats, Reform UK and the Green Party. (Plenty also stayed at home: fewer than three-fifths of eligible voters turned out to vote, the second-lowest turnout in the past century).

Yet the implication of voting for other parties—ie, a victory for Sir Keir—was clear before the election. The Conservatives themselves hammered home the message that a vote for Reform uk or the Liberal Democrats would result in a Labour “supermajority”. Voters plainly thought this was no bad thing. The Conservatives lived by first past the post, now they had to die by it.

England has been using first-past-the-post systems for centuries and exported to many of its former colonies, including the United States and Canada. It’s what we’re used to. But it’s not exactly democratic.

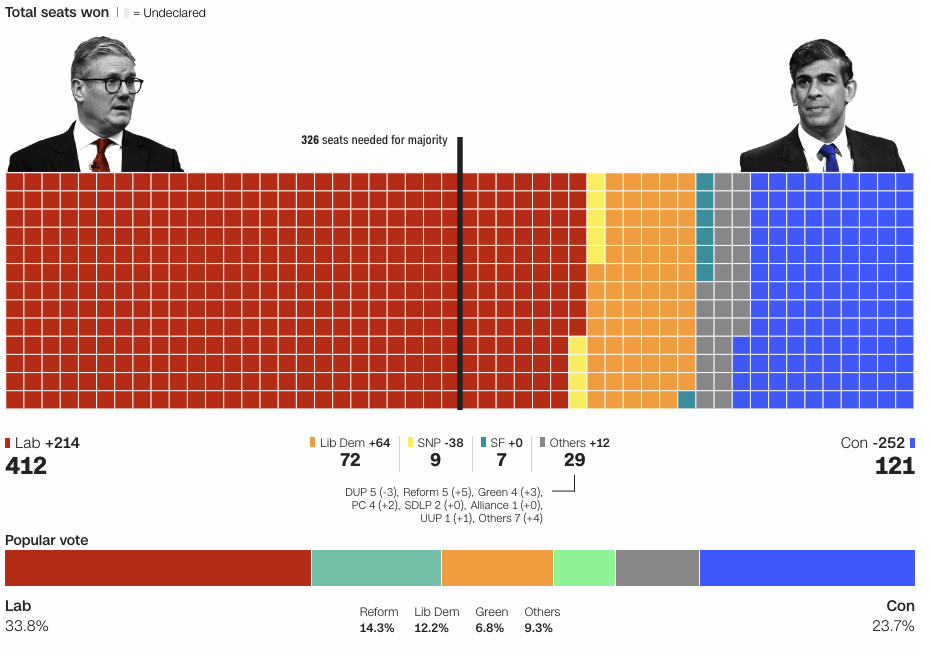

The election was clearly—and justly—a rejection of the Tories after years of poor governance. While the outcome was a Labour landslide, winning 412 of the 650 seats in the Commons (63.4%), they only received 33.8% of the votes.

CNN has this graphic:

CNN notes,

Because of its electoral system, Britain can see large discrepancies between the share of seats won by a party and its share of the popular vote.

If support for one party – or antipathy toward another – is spread fairly evenly across the country, it does not need to win a large share of the popular vote to win a huge majority of seats in parliament. Labour secured its landslide victory even as it won just about a third of the popular vote.

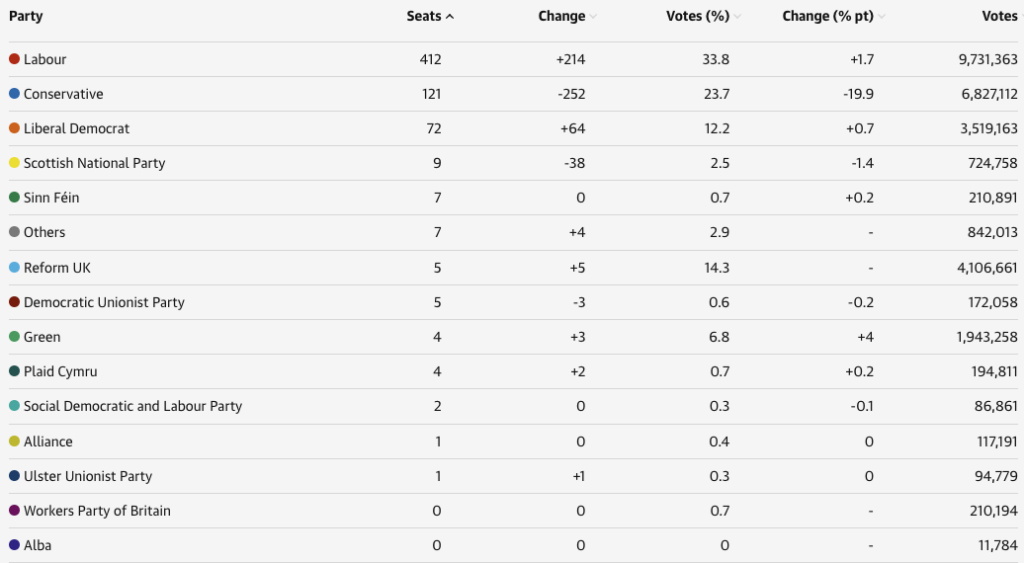

It works the other way, too. Here’s a different representation of the data from The Guardian:

Note how wildly the allocation of seats differs from the voting. Reform UK actually received considerably more votes than the Liberal Democrats, yet received only 5 seats to LP’s 72. Indeed, Sinn Féin, which received fewer votes than the delta between RUK and LP, got more seats than LP.

To be sure, this is a function of single-member districts as well as FPTP. But, unlike the US House, people are only nominally voting for their individual representative. Indeed, MPs are not required to live in their constituency and it’s quite common for senior members of a party to run for “safe” seats to which they have no personal connection. Voting for the Commons is more about selecting a Prime Minister than about one’s local MP.

I wonder how British voters would feel about ranked choice voting.

And then there is France…

@Kathy: They rejected it in a referendum in 2011.

Although the main solution is some type of PR.

@Andy: France uses a modified two-round process in single-seat districts. It will be interesting to compare first round vote share, to the second, to the seat count.

To the point of the OP, it is quite clear that FPTP elections doing a very poor job of actually representing the interests of voters.

There is also a typical lack of self-awareness in the CNN quote. We have the same system (although filtered through primaries, which makes it a kind of two-step process) and as a result, it happens on occasion that the party with the fewer voters gets the most seats.

But we rarely report it out the data the way the British do.

@Steven L. Taylor: For sure. The UK model is arguably worse in that sense than ours because they have so many more parties dividing the vote, rather than just about everyone settling for their least unfavorite of the two major parties. (Although, granted, that works both ways: several minor parties at least got a few seats.) And I do think a Westminster-style parliamentary system is fundamentally different in that legislative elections are effectively elections for heads of state.

@James Joyner:

Absolutely!

But, while certainly party behavior is affected by either parliamentarism and presidentialism, the fundamental effects of the electoral rules across cases is pretty clear regardless of how the executive is chosen.

Side note: I believe our party system would look a lot more like the UK’s if we didn’t have primaries and had, by extension, stronger parties that had control over candidate selection.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Can you clarify what you mean? Do you mean number of parties that win seats in Congress?

@Kurtz: Both competing for and winning seats, yes.

@Kathy:

I wonder how American voters would feel about seating bishops and hereditary peers in the legislative body. I marvel at the medieval anachronisms of UK governance.

Under the Australian system of preferential voting, the election would have been very close provided the Reform and Conservative voters exchanged preferences in disciplined fashion (i.e. R1, C2 or vice versa, with everyone else further down the ballot). The winner would probably have been decided by the preferences of the smaller parties. IMHO this would have been a much more accurate reflection of voters’ wishes, and allowed far more people to feel that their vote had mattered.

@DK: I’m not sure hereditary peers are any more subversive of good governance than political dynasties like the Bushes and Kennedys.

Franky, for the past decade they have been the most knowledgeable and sane actors in the system by far. Make of that what you will :D.

Ian Dunt has written a somewhat dry but very perceptive book about the whole mess.