Did The Supreme Court ‘Overrule’ Korematsu? Not Really

Contrary to what many people have claimed, the Supreme Court's decision in Trump v. Hawaii did not overturn one of the most controversial decisions in its history.

Yesterday’s ruling by the Supreme Court in Trump v. Hawaii, which will be the subject of debate and discussion for years to come, contained one bit of interesting commentary from Chief Justice Roberts that is leading some to conclude that the Supreme Court has overruled one of the most controversial decisions in its history:

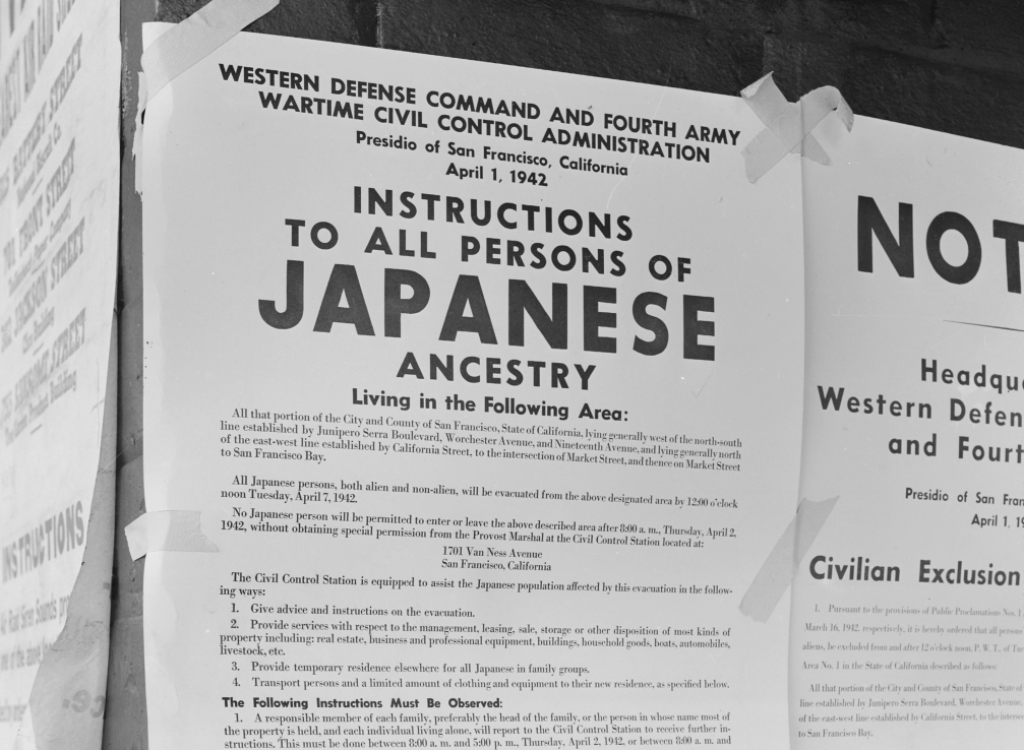

WASHINGTON — In the annals of Supreme Court history, a 1944 decision upholding the forcible internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II has long stood out as a stain that is almost universally recognized as a shameful mistake. Yet that notorious precedent, Korematsu v. United States, remained law because no case gave justices a good opportunity to overrule it.

But on Tuesday, when the Supreme Court’s conservative majority upheld President Trump’s ban on travel into the United States by citizens of several predominantly Muslim countries, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. also seized the moment to finally overrule Korematsu.

“The forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of presidential authority,” he wrote. Citing language used by then-Justice Robert H. Jackson in a dissent to the 1944 ruling, Chief Justice Roberts added, “Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and — to be clear — ‘has no place in law under the Constitution.'”

In a dissent of the travel ban ruling, Justice Sonia Sotomayor offered tepid applause. While the “formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue,” she said, it failed to make the court’s decision to uphold the travel ban acceptable or right. She accused the Justice Department and the court’s majority of adopting troubling parallels between the two cases.

In both cases, she wrote, the court deferred to the Trump administration’s invocation of “an ill-defined national security threat to justify an exclusionary policy of sweeping proportion,” relying on stereotypes about a particular group amid “strong evidence that impermissible hostility and animus motivated the government’s policy.”

The fallacies in Korematsu were echoed in the travel ban ruling, warned Hiroshi Motomura, a University of California, Los Angeles, law professor who has written extensively about immigration.

“Overruling Korematsu the way the court did in this case reduces the overruling to symbolism that is so bare that it is deeply troubling, given the parts of the reasoning behind Korematsu that live on in today’s decision: a willingness to paint with a broad brush by nationality, race or religion by claiming national security grounds,” he said.

He added, “If the majority really wanted to bury Korematsu, they would have struck down the travel ban.”

(…)

The travel ban case, however, brought Korematsu back to the forefront. It traced back to Mr. Trump’s campaign proposal in 2015 to categorically bar Muslims from entering the United States. At the time, Mr. Trump cited with approval Roosevelt’s actions, including wartime restrictions placed on Americans of Japanese, German and Italian ancestry, and said he was not going that far.

“Take a look at what F.D.R. did many years ago,” Mr. Trump said at the time. “He did the same thing.”

Over time, Mr. Trump’s call for a complete ban on Muslims entering the United States evolved into a ban on entry by nationals from a list of troubled countries, most of which were predominantly Muslim. Under the law, the president has the authority to bar groups of foreigners for national security reasons.

The issue of the parallels, if any between the Court’s decision on the travel ban and Japanese internment were raised by Justice Sonya Sotomayor in her dissent:

Today’s holding is all the more troubling given the stark parallels between the reasoning of this case and that of Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 (1944). See Brief for Japanese American Citizens League as Amicus Curiae. In Korematsu, the Court gave “a pass [to] an odious, gravely injurious racial classification” authorized by an executive order. Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña, 515 U. S. 200, 275 (1995) (GINSBURG, J., dissenting).As here, the Government invoked an ill-defined national-security threat to justify an exclusionary policy of sweeping proportion. See Brief for Japanese American Citizens League as Amicus Curiae 12-14. As here, the exclusion order was rooted in dangerous stereotypes about, inter alia, a particular group’s supposed inability to assimilate and desire to harm the United States. See Korematsu, 323 U. S., at 236-240 (Murphy, J., dissenting). As here, the Government was unwilling to reveal its own intelligence agencies’ views of the alleged security concerns to the very citizens it purported to protect. Compare Korematsu v. United States, 584 F. Supp. 1406, 1418-1419 (ND Cal.1984) (discussing information the Government knowingly omitted from report presented to the courts justifying the executive order); Brief for Japanese American CitizensLeague as Amicus Curiae 17-19, with IRAP II, 883 F. 3d, at 268; Brief for Karen Korematsu et al. as Amici Curiae 35-36, and n. 5 (noting that the Government “has gone to great lengths to shield [the Secretary of Homeland Security’s] report from view”). And as here, there was strong evidence that impermissible hostility and animus motivated the Government’s policy.

Although a majority of the Court in Korematsu was willing to uphold the Government’s actions based on a barren invocation of national security, dissenting Justices warned of that decision’s harm to our constitutional fabric. Justice Murphy recognized that there is a need for great deference to the Executive Branch in the context of national security, but cautioned that “it is essential that there be definite limits to [the government’s] discretion,” as “[i]ndividuals must not be left impoverished of their constitutional rights on a plea of military necessity that has neither substance nor support.” 323 U. S., at 234 (Murphy, J., dissenting). Justice Jackson lamented that the Court’s decision upholding the Government’s policy would prove to be “a far more subtle blow to liberty than the promulgation of the order itself,” for although the executive order was not likely to be long-lasting, the Court’s willingness to tolerate it would endure. Id., at 245-246.

Roberts responded to Sotomayor with this short piece at the end of the majority’s 38-page opinion:

Finally, the dissent invokes Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 (1944). Whatever rhetorical advantage the dissent may see in doing so, Korematsu has nothing to do with this case. The forcible relocation of U. S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority. But it is wholly inapt to liken that morally repugnant order to a facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission. See post, at 26-28. The entry suspension is an act that is well within executive authority and could have been taken by any other President—the only question is evaluating the actions of this particular President in promulgating an otherwise valid Proclamation.

The dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—“has no place in law under the Constitution.” 323 U. S., at 248

This has led many in the media and several legal pundits, such as George Washington University Law Professor Jonathan Turley, hailed Robert’s response to Sotomayor and took it as a sign that one of the darkest blots on the Supreme Court’s record had, finally, been overruled. As Scott Bomboy at the National Constitution Center points out, though, that really isn’t what Roberts did:

But can the Korematsu decision be overruled without a specific case about it appearing at the Court?

We asked our long-time friend and contributor Lyle Denniston, who has covered the Supreme Court since the late 1950s, for a ruling.

“While two dissenting Justices praised the Court for ‘finally overruling’ that 1944 precedent, the majority did not actually do so, for several reasons,” Denniston said. “First, there was no request by the parties in the case to do that in this case so that was not an issue before the Justices; second, the language of an explicit overruling was not used; third, the majority said that the ruling ‘has been overruled by history’ — which is not the same as an actual overturning of the precedent. The majority’s negative sentiments about it are what judges and lawyers call ‘dicta’ — statements made in a court opinion that do not affect the actual outcome.”

Dicta, however, can be understood to be powerful statements on their own. Two examples from the Court are the famous “Footnote Four” from the Carolene Products decision (about the Court’s rationale for declaring laws unconstitutional) and statements about the Alien and Sedition Acts in New York Times v. Sullivan.

Prior Justices haven’t been bashful about criticizing Korematsu. The late Antonin Scalia cited Justice Robert Jackson’s dissent as his favorite Supreme Court opinion of all time. Scalia said in 2014 he admired Jackson’s opinion for its writing style and for the fact that “it was nice to know that at least somebody on the court realized that that was wrong.”

About a year later, Justice Stephen Breyer told ABC News on Sunday he didn’t see mass internment of ethnic groups in the nation’s future, in a reference to Korematsu. “This country has developed a stronger tradition of civil liberties,” Breyer said about Korematsu’s legacy. “I think everyone I’ve ever run into thinks that case was wrongly decided.”

Although in 1983 federal courts overturned Korematsu’s original convictions, the Supreme Court never has had an opportunity to overturn the 1944 decision in an official way. Today’s statements by Roberts and Sotomayor may be the closest the Court will ever come to doing that in the near future.

On some level, I suppose, it is good to see the Chief Justice repudiate one of the Court’s most notorious decisions in its entire history, ranking right up there with Dred Scott v. Sandford and Plessy v. Ferguson in terms of not only the bad reasoning but also the rather obviously bad impact that the ruling had on politics and society going forward. A quick survey of American history makes clear why that is the case.

While some kind of conflict regarding the future status of slavery in the United States was probably inevitable regardless of how the Court ruled in Dred Scott, the ruling it handed down made that conflict inevitable and reinforced racist attitudes toward African-Americans that formed the entire basis for secessionist movement after the 1860 election and the racist basis on which the Confederacy itself was founded. Similarly, laws and other social norms intended to keep African-Americans from achieving the freedom and equality that were guaranteed to them by the blood spilled in the Civil War and the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment were in existence before Plessy was handed down but the Court’s decision helped to cement those laws and norms in place, neuter the Fourteenth Amendment for the better part of the next half-century, and lead to the rise of the Jim Crow State in the south that persisted until the Civil Rights Movement came along. Korematsu did not have the same long-term impact that those two decisions did, of course, but it legalized an action that was inherently immoral and racist, especially given the fact that the government at the time did not choose to treat citizens and residents of German or Italian ancestry in a similar manner notwithstanding the fact that they too came from countries that had declared war against the United States. Dred Scott, of course, was ultimately overruled by the fact of how the Civil War turned out and the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, while Plessy was overruled by the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. While Korematsu has been criticized as harshly as these other two cases, on the other hand, it has never been explicitly overruled. In no small part, this is because the issues it dealt with have not come before the Court again, although as noted above the decision itself has been repudiated repeatedly by sitting members of the Supreme Court and it’s clear that nobody considers it to be good law at this point.

All that being said, though, it’s technically not correct to say that Korematsu was overruled yesterday. The most important reason why is the one pointed out by Lyle Denniston in Scott Bomboy’s piece quoted above. In short, neither Korematsu nor the issues it raises were before the Court nor was it involved in the legal issues that were before the Court. Indeed, Roberts would likely not have even the mentioned the case had it not been for the fact that Sotomayor raised it in her dissent, and she did so as a rhetorical device against the majority opinion citing an argument raised by in an amicus curiae brief by a civil rights organization. As such, the Court’s language regarding Korematsu is what is known in the law as dicta, which basically means an opinion expressed by a Judge in a ruling that does not “embody the resolution or determination of the specific case before the Court.” (Source) As a result, even if one assumes that what Roberts said about Korematsu, it is not binding legal precedent. Despite this caveat, it is good to see the Court, through the Chief Justice, consign Korematsu to the dustbin of history so to speak. Even though it is really nothing more than a rhetorical flourish, it does count for something.

I’m troubled by the qualification. It implies one can throw US citizens, and for that matter immigrants and even tourists, into concentration camps so long as it’s not on the basis of race.

Further, if Korematsu still stands, doesn’t that mean any president still has the legal power to throw people into concentration camps, even solely on the basis of race, should they so desire?

But apparently a conservative Supreme Court will be able to justify any racist policy of this administration by simply being unable to see the similarities with Korematsu.

Not exactly a profile in courage.

I understand that the majority justices gave no weight to Trump’s public remarks concerning his proposed travel ban, but that seems to me to be a very narrow approach – has it always been the case that a president’s remarks concerning his requested legislation do not matter?

Korematsu was cool. Kirk didn’t believe in a No Win Scenario so he hacked the test! 😛

Ignoring the President’s clearly stated animus, and deferring to a vague statement of national security is a very dangerous precedent, and it’s the heart of this case and Korematsu.

It’s a tough balancing act — determining entry into the United States is typically an executive prerogative, and national security is as well — but where there is clear animus, I think Court review, and a higher standard than “President gets what he wants” is required.

We should have a clear accounting of what the criteria for inclusion are, what countries naturally meet those criteria, and what countries are being added/removed from the list for additional factors. We need that as a check on the clearly stated animus.

Part of the problem of this case is that congress is supposed to be doing oversight of the executive branch, and just isn’t bothering to do so, so the courts are being used to attempt to get that oversight.

@Kathy:

Yes. And despite John Roberts statements above, I wouldn’t count on “balls and strikes” Roberts to oppose it. They’d pretend it wasn’t race, or political persuasion, do a lot of hand waving about “security”, and somehow work free speech into it, and Roberts has just shown he can ignore any amount of evidence as to their real motives.