Europe Becoming Poorer?

The Eurozone is falling further behind the United States.

Tom Fairless, who covers Europe’s economy for the WSJ, reports “Europeans Are Becoming Poorer. ‘Yes, We’re All Worse Off.’“

Europeans are facing a new economic reality, one they haven’t experienced in decades. They are becoming poorer.

Life on a continent long envied by outsiders for its art de vivre is rapidly losing its shine as Europeans see their purchasing power melt away.

The French are eating less foie gras and drinking less red wine. Spaniards are stinting on olive oil. Finns are being urged to use saunas on windy days when energy is less expensive. Across Germany, meat and milk consumption has fallen to the lowest level in three decades and the once-booming market for organic food has tanked. Italy’s economic development minister, Adolfo Urso, convened a crisis meeting in May over prices for pasta, the country’s favorite staple, after they jumped by more than double the national inflation rate.

With consumption spending in free fall, Europe tipped into recession at the start of the year, reinforcing a sense of relative economic, political and military decline that kicked in at the start of the century.

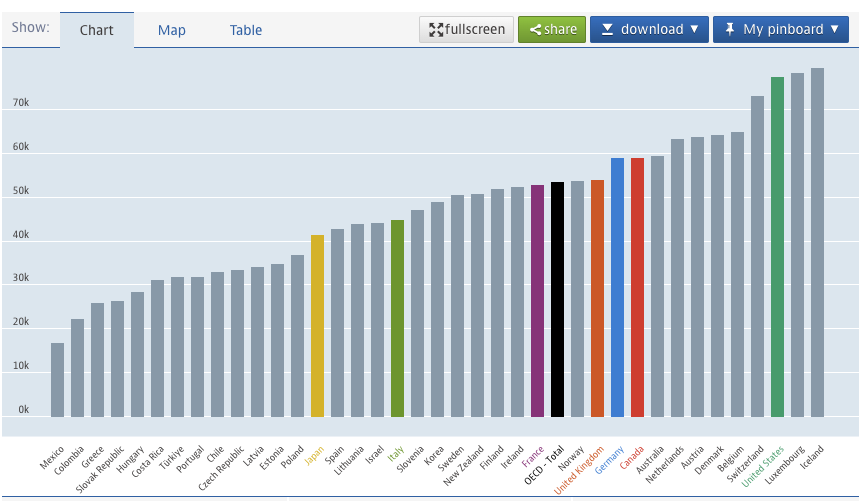

He supplies the following chart (interactive at the link):

Two things stand out: the average American wage is way higher than that even in Germany and France, which I think of as very rich countries. But, two, only Greece has suffered a significant decline since 2019 the others look like minor declines that you’d expect in a recession.

It’s noteworthy, too, that some of the richer countries are excluded. Here’s the chart presented atop the OECD average wage page:

Still, it’s remarkable that only Luxembourg and Iceland, both tiny countries, have higher average salaries than the US. (Is “average” the wrong measure?* Is the mean distorted by the extreme wealth at the very top of the income distribution here more so than in Europe?)

Fairless continues:

Europe’s current predicament has been long in the making. An aging population with a preference for free time and job security over earnings ushered in years of lackluster economic and productivity growth. Then came the one-two punch of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s protracted war in Ukraine. By upending global supply chains and sending the prices of energy and food rocketing, the crises aggravated ailments that had been festering for decades.

Governments’ responses only compounded the problem. To preserve jobs, they steered their subsidies primarily to employers, leaving consumers without a cash cushion when the price shock came. Americans, by contrast, benefited from inexpensive energy and government aid directed primarily at citizens to keep them spending.

Okay. But that’s a temporary blip, right? I don’t think there’s another massive “relief” bill on the horizon and the supply chain situation seems to be sorting itself out.

In the past, the continent’s formidable export industry might have come to the rescue. But a sluggish recovery in China, a critical market for Europe, is undermining that growth pillar. High energy costs and rampant inflation at a level not seen since the 1970s are dulling manufacturers’ price advantage in international markets and smashing the continent’s once-harmonious labor relations. As global trade cools, Europe’s heavy reliance on exports—which account for about 50% of eurozone GDP versus 10% for the U.S.—is becoming a weakness.

That’s a more serious issue, assuming China’s seemingly unsustainable growth has finally done what unsustainable things do. Germany, in particular, has long been known as a massive exporter.

Private consumption has declined by about 1% in the 20-nation eurozone since the end of 2019 after adjusting for inflation, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a Paris-based club of mainly wealthy countries. In the U.S., where households enjoy a strong labor market and rising incomes, it has increased by nearly 9%. The European Union now accounts for about 18% of all global consumption spending, compared with 28% for America. Fifteen years ago, the EU and the U.S. each represented about a quarter of that total.

This is quite interesting. Is this simply a cultural difference? How much of this is wealth versus profligate spending on credit? How much is a function of differential taxes on consumption?

Adjusted for inflation and purchasing power, wages have declined by about 3% since 2019 in Germany, by 3.5% in Italy and Spain and by 6% in Greece. Real wages in the U.S. have increased by about 6% over the same period, according to OECD data.

If the point is to compare the United States and “Europe,” then it would make more sense to point to the average of European OECD countries, not seemingly random individual countries. I don’t have the time this morning to do that calculation.

After a few paragraphs of anecdotal color, Fairless reports,

Weak spending and poor demographic prospects are making Europe less attractive for businesses ranging from consumer-goods giant Procter & Gamble to luxury empire LVMH, which are making an ever-larger share of their sales in North America.

“The U.S. consumer is more resilient than in Europe,” Unilever’s chief financial officer, Graeme Pitkethly, said in April.

The eurozone economy grew about 6% over the past 15 years, measured in dollars, compared with 82% for the U.S., according to International Monetary Fund data. That has left the average EU country poorer per head than every U.S. state except Idaho and Mississippi, according to a report this month by the European Centre for International Political Economy, a Brussels-based independent think tank. If the current trend continues, by 2035 the gap between economic output per capita in the U.S. and EU will be as large as that between Japan and Ecuador today, the report said.

Assuming that a consistent definition of “Eurozone” is used (most notably, the UK has left in the intervening period, so it would be absurd to directly compare 2008 and 2023 without accounting for that) this is startling, indeed. (And, as one with deep ties to Alabama, that even the Europeans can now say, “Thank God for Mississippi” amuses me greatly.)

Weak growth and rising interest rates are straining Europe’s generous welfare states, which provide popular healthcare services and pensions. European governments find the old recipes for fixing the problem are either becoming unaffordable or have stopped working. Three-quarters of a trillion euros in subsidies, tax breaks and other forms of relief have gone to consumers and businesses to offset higher energy costs—something economists say is now itself fueling inflation, defeating the subsidies’ purpose.

Public-spending cuts after the global financial crisis starved Europe’s state-funded healthcare systems, especially the U.K.’s National Health Service.

The US is one of the few exceptions within the OECD to the problem that rich people have fewer children which, combined with people in rich countries living longer, makes a generous welfare state difficult to sustain. There simply not enough working people to pay for a massive number of retirees. The US has mitigated the problem with not only a less generous welfare system—which is arguably a bad thing—but with high rates of immigration, compounded by the newer immigrants tending to have more children.

While I’ve skipped all the other anecdotes, this one is a doozy:

Noa Cohen, a 28-year old public-affairs specialist in London, says she could quadruple her salary in the same job by leveraging her U.S. passport to move across the Atlantic. Cohen recently got a 10% pay raise after switching jobs, but the increase was completely swallowed by inflation. She says friends are freezing their eggs because they can’t afford children anytime soon, in the hope that they have enough money in future.

Whether that’s representative, I haven’t a clue. And it’s quite probable that we’re over-paying our public affairs specialists.

With European governments needing to increase defense spending and given rising borrowing costs, economists expect taxes to increase, adding pressure on consumers. Taxes in Europe are already high relative to those in other wealthy countries, equivalent to around 40-45% of GDP compared with 27% in the U.S. American workers take home almost three-quarters of their paychecks, including income taxes and Social Security taxes, while French and German workers keep just half.

Which, of course, isn’t new and was long touted as why life in Europe was often better: they could afford everything from free healthcare and university educations to longer vacations. But, again, that only works when there are enough people in the workforce to keep feeding the system.

There’s a whole lot more but that’s the gist of the report.

It was presumably sparked by the recent release of OECD wage figures but I’m not seeing other reports in a similar vein. My natural instinct was “Well, this is the Wall Street Journal,” but we’re not talking about the editorial page. But there have been periodic reports over the last few years elsewhere (See, for example, the Feb. 2019 NYT report “Europe’s Middle Class Is Shrinking. Spain Bears Much of the Pain.“) so I don’t think this is just a pro-business paper poking at the welfare state.

____________

*Here’s how OECD is defining the metric: “Average wages are obtained by dividing the national-accounts-based total wage bill by the average number of employees in the total economy, which is then multiplied by the ratio of the average usual weekly hours per full-time employee to the average usually weekly hours for all employees. This indicator is measured in USD constant prices using 2016 base year and Purchasing Power Parities (PPPs) for private consumption of the same year.”

Drum has a piece out already debunking the whole premise of the article. As is typical of the WSJ opinion section, they neglect inflation when necessary to craft their narrative. Drum corrects for inflation showing very different results, basically that the US is doing better than most of Europe in a variety of measures but the Continent is still showing growth.

I’d be interested in seeing median wage rather than average wage, as I suspect a lot of the increased growth in the US is concentrated in a small group at the top of the income curve

There’s lots of truth here, but some of the analysis shows an ideological bias that the author appears not to reckon with. For example, how much of our bigger average salary is eaten up by our higher individual healthcare and education spending that is collectivized in some of these countries? Is that offset by the lower taxes Americans pay or not? The piece doesn’t delve into questions like these.

And what does “weak spending” even mean? My personal experience is that my European friends think I, as an American, spend way too much. The first thing I did –upon taking up a Danish buddy on his offer to host me at his Berlin apartment — was to start buying when I arrived: paper towels, the nuts and yogurt on which I subsist, wine for us, gifts for him, and extra bedding because his was threadbare.

He enjoyed that immensely, but he also said, “Ah, you are typical materialistic American consumerist.” I was offended!

I don’t know that my friends are representative, but they do not tend to spend a lot relative to Americans, despite having very good jobs. None of them buy paper towels, they do not own dish drainers, they do not run air conditioning, the bedding/sheets situation is always harrowing for me etc. What the WSJ calls “weak spending” they would probably call “sensible spending.”

As a point of clarification in re the Opinion piece

The UK was never and has never been part of the Eurozone. Eurozone =/= European Union as not all EU members have adopted Euro.

Otherwise WSJ opinion pieces should generally not be bothered with. If you wish proper financial news, and analytics that are not bizarre ideological fun-house mirror writing, The Financial Times is far superior.

@MarkedMan: Drum has a weak understanding regrettably of how to use Deflators and frequently thus writes nonsense on inflation (nonsense technically quite aside from his politics) – that said a quick perusal of his post, his points seem to be correct.

There could be a serious point here. Walking around Europe, I have noticed that the people are noticeably thinner. This probably reflects food insecurity. We use the extra income to spend on healthcare to get our exceptional life expectancy results.

@Lounsbury: Drum also definitely has a bias towards the “nothing to see here” analysis. I think he often jumps to that conclusion too early. That said, his hobbyhorse about including inflation is dead on. There is simply no legitimate reason not to include it in multi year wage/salary/purchasing type of information and failure to do so is a sign of either weak understanding of your subject or, as is all too often the case with the WSJ opinion section, an attempt to “lie by statistics”

Looking at PPP adjusted per capita GDP, it does seem like Europe has stagnated relative to the US since 2008.

Matt Yglesias recently had a piece on this and attributed much higher relative US performance to fracking, immigration, and silicon valley, among other factors. Energy and immigration are two areas where the US excels compared to Europe.

@DK:

My German in-laws are pretty much the same, except that after having visited us in the States a couple times they changed a couple things: now they do buy paper towels, and they installed window screens in their bathrooms and kitchen.

They don’t run air conditioning because they don’t have it, although with our rapidly heating world causing more heat in Europe that may change for a lot of Europeans. A couple days ago it hit 102F in northern Bavaria which was entirely unheard-of when I lived there in the early 1990s.

My wife and I have German bedding which we find far superior to the American sheets and blankets thing.

@MarkedMan: His hobbyhorse re inflation and using deflated figures willy nilly is applied in a fashion typical of people with partial understanding of a subject and thinking they have grand insights… as compared to normal journalists who are innumerates this is true.

It is overdone.

There is a real and legitimate utility to using deflated numbers over long time series of economic data as one reduces what we call “money illusion.”

That does not mean one runs around deflating every figure and then mix nominal analysis (inflation) with deflated analysis (as he does frequently and completely incoherently).

If the time series is over a long enough period, yes, it makes sense. Over 3 or 5 years to use a rule of thumb.

@Andy: the appropriate point of comparison relative to the subject is to use a deflated version. Constant 2015 for example (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?locations=EU-US). There is a divergence although variability within EU (and an issue of constance in benchmark from 2016 as UK is in EU zone for most period, a Eurozone based analysis would be more appropriate to control for UK effect including GDP underperformance post Brexit vote). (ETA a better view can be had via 2015 base dollars, and by members on GDP per capita: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?locations=US-FR-DE-NL-DK-ES-IT-BE-SE-PT)

There are of course important structural points, one should look at distribution within EU (quite skewed) and account for Eastern Europe expansion – the entity “EU’ is not constant in period contra USA which is; it is adding Middle Income members in Eastern Europe, most recently Croatia for example).

So you really should restrict peer to peer for comparison, W. Europe, in order to speak to divergence effects.

@Slugger: oh, that is some dry sarcasm. Well done.

The central problem of economics is reconciling unlimited desires and limited means. Europeans have perhaps more limited ‘unlimited desires.’ Maybe more of them are capable of saying, enough.

Years back I decided to pick an ‘enough’ point where, if I reached it, I’d start giving new income away. As I age I reduce that number – I ain’t living forever, so it’s mostly about leaving enough for the kids.

I made the transition from poor working stiff to not-poor author all too easily. I’ve spent a grand on a meal. (Well, that includes wine and tip). I buy nice cars and fly business class and stay in suites at excellent hotels, all that. But I never wanted a private plane or a yacht or, god forbid, a house big enough to require staff. WTF would I do with a Lambo except drive it into a wall? So, I decided if I have X, Y and Z, I’m happy. Because the object is to achieve happiness not just to grab more, always more. I don’t want to die with my arthritic hands grasping for another dollar.

TBH if I could escape the IRS and double taxation I’d already be living in Europe. I’d have bailed in 2016 if not before.

@Gustopher: It had a certain panache.

I’m skeptical about that reporting on the salaries. Is that pre- or post-taxes? When I was quoted my salary when working in Japan, it was in terms of what would show up in my bank account after taxes had been withheld.

Also, considering the number of obscenely rich billionaires we have in the US, it wouldn’t surprise me that the top 0.1% of Americans are dragging that statistic up. Give us the mean as well as the median salaries.

We pay more, because it’s a more in-demand field in the US. Every state has a State House, Governor, etc., and we have the same at the federal level. THEN, we have lobbyists for every conceivable US industry. Now layer in our ridiculous PAC structures and campaign expenditures.

There is a far, far, far more active public affairs field here in the US than the UK. Greater demand, higher salaries.

Signed,

A Former Public Affairs PR Person.

@Mikey:

With my chosen family in Deutschland — who are from all over the continent — they will admit they have access to superior product. They just decline to buy it.

I go could on and on about the things I “have” to buy when camping at one of their homes for a week, prompting appreciative thanks but also bemusement at my consumerist American ways. I managed to influence a couple in Charlottenburg, Berlin to start stocking yogurt and almonds but lost the paper towel battle. It’s not for them pleading poverty: one half is a doctor who runs a hospital psychiatric ward, the other teaches Norwegian and English to children of diplomats. They have a lovely, airy flat with hardly anything in it — perfect for the houseparties they often host.

So I can see why European consumers like these frustrate the business investors noted in the WSJ. I’m apparently a marketing drone like most Americans, I suspect many in the so-called Eurozone are impervious. I just now occurs to me hardly any of my friends own a television set, my ex in Barcelona being the one exception that immediately comes to mind. Every American I know own a TV (I barely watch mine…but I bought it). Would love to see actual data on that.

We maybe have something to learn from this minimalism.

@Lounsbury:

Hey don’t forget about those newcomers, Alaska and Hawaii…

@Michael Reynolds:

I agree with this, but it triggers a comment. I’ve been reading The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism by Martin Wolf. In his narrative the central problem is threading a needle between economic control of politics and political control of the economy. Between oligarchy and socialism. Oligarchy, the goal of the Kochtopus, or for real socialism, government owns the factories, not Swedish, or Bernie Sanders, Democratic Socialism.

Based on income distribution Europe has stayed further away from oligarchy. Which supports the question several commenters have asked – are U. S. numbers skewed by high inequality. One would assume they are. Mean, rather than average, numbers might tell a different story.

@MarkedMan: “in period”

@gVOR10:

Socialism can be a nebulous, amorphous term. I recall from high school history many variants of it emerged in the XIX century, largely as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution and the many excesses of early capitalism.

Forms of socialism went from simple reforms like a 40-hour workweek and decent pay, to Marx’s dictatorship of the proletariat (spoiler alert: that’s not what the Soviets ultimately did).

It’s still somewhat ill-defined. Except perhaps in the US, where it is whatever the GQP says it is. More seriously, it might be stripped down to government regulation of the economy. But that goes back a long way, and it was even advocated by prominent socialists like Adam Smith 😉

In countries other than America, state-owned companies are rather common. At one time in Mexico the state owned not only the oil company and the electric utilities (there were two), but also the phone company, an airline, all newsprint manufacturing, TV networks*, steel mills, mines, and lots more. Much of that has devolved to private ownership. Oil and electricity remain near-total government monopolies.

But there’s always been a private sector involved in commerce, manufacturing, mining, and services.

This state of affairs was often called a mixed economy. It has rarely been called socialism.

*There was always private TV stations and networks, and since the 70s cable as well. Plus the federal government sold off its networks. There still remain some stations owned by individual states, and one network owned by a public university (and it’s been years since I watched either).

@Kathy:

Capitalism has the same problem. In the same way that the state didn’t “wither away,” the rising tide of prosperity has never managed to raise all the boats equally effectively, nor has the wealth from productivity gains and all the various incentives to the producers of wealth ever managed to trickle down to every level of society.

Still, the owners of capital are doing fine and isn’t that what really matters?

Just on some of the comments wondering if the super rich are distorting the US average wage in those graphs: the super rich don’t collect a monthly salary. Billionaires don’t get paychecks, and they’re not typically employees. They own assets that appreciate in value and collect dividends or rents from them, so they’re probably not having much of a distorting effect and the graphs are likely a reasonably accurate reflection of reality.

Just noticed this bit:

That’ll be because that 50% includes intra-EU trade.

To get an comparable statistic means counting trade between US states as exports.

The actual figures are around 20%.

Sloppy.

@MarkedMan: This wasn’t an editorial, it’s a report from their World section.

@Stormy Dragon: I noted that possibility in the OP. Unfortunately, OECD tracks the average, albeit in a rather odd way.

@Lounsbury: I knew that! Because of the way the piece was framed, I just naturally translated “Eurozone” to mean “the European members of the OECD.” It’s one of the problems of the piece, I think: it doesn’t use a consistent group for comparison.

@MarkedMan: Again, not the opinion section. And these are inflation-adjusted numbers straight from the latest OECD report (which I linked and screenshotted in the OP).

@Just nutha ignint cracker: the mixture of incorrect and invented.

,

“equally effectively” is not a claim made for private markets or “capitalism” for “rais[ing]” boats, that is economic benefit, that being a Leftist framing not an internal claim, unlike State withering away.

So an invented apple-orange comparison based on conceptual claim not actually occuring on one side

This is quite simply and evidently untrue, the poor of wealthy OECD are clearly objectively more resourced than the poor in low income countries – starvation and famine no longer occur. Further the enormous reduction globally in absolute poverty over the past three decades, as summarised and available in World Bank data do indicate a broad effect.

Now without doubt private market capitalism has not met Socialists and other hard Left’s goals of a leveled society, but they are not the internal goals of private market economics. Of course if you set Capitalism up as if it were an ideology like Communism and set as performance metrics those of the socialist Left, well… you will achieve insights worthy of the persipacity of the Wall Street Journal opinion pages.

@James Joyner: ah not an editorial. Well then sloppy journalism as it is comparing unlike things and the EU as either its broad membership or by Eurozone sub-definition is not the same entity in 2000 as in 2008 as in 2023 in terms of geographic coverage, notably important being the progressive addition of Eastern European members.

One needs to compare like to like, which for this kind of purpose really should be the highest income long-term EU members (as like https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?locations=US-FR-DE-NL-DK-ES-IT-BE-SE-PT) where one does seem some effect along these lines but an important differentiation between the North ex-German and the relative south. The point may be made here that it is frequently observed that the Nordic (or one could say Nordic-Dutch) model of great market flexibility than the control oriented French model (applicable to the ‘Latins’ generally in broad terms) combined with strong but targetted social support is more effective economically.

Certainly the French system as seen by recent riots is one that does a poor job of integration and job creation for new job entrants – something observed really since the 1980s. The weaker Latins performance in growth is likely heavily due to this economic model choice, their similarities in form of labour code, other non-market friendly interventions are in contrast with the Nordics

@Stormy Dragon: on memory the data do reflect an overweight although not as narrow as Lefties like to present nevertheless a concerning overweight particlarly my recollection the lowest quartile have not seen real wage growth in decades while the next quartile has rather weak real wage growth.

That is not simply to be shrugged off as it is dangerous politically – the differing internal geographical impacts of this likely go quite the long way to explaining the MAGA phenomena in combination with the social effects that come along with this plus other social change.

@MarkedMan: Exactly. Americans as well are putting off children and are unable to buy homes and we don’t have that robust social services net…

@Andy: Wage averages and industrial productivity are fools metrics when you consider the extreme wealth inequality that exists in the USA (not to speak of my own dear United Kingdom, where we are wrestling with an apocalyptic combination of severe inequality AND low output).

The notion that people are getting ‘poorer’ in the Eurozone is laughable when you look at the sheer scale of the decline of the American middle class – or the frankly appalling conditions that those living precariously are forced to suffer due to an inadequate social security net. All this is downstream of an oligarchic 0.1% and their enabling servants that lead the professional class.

I’d suggest Americans get their own house in order before critiquing the European economic model. It’s an apples vs. pears comparison argued on the proviso that we all buy into the well-debunked Hayekian arguments in favour of deregulation and free market extremism. Perhaps compare the totals for deaths of despair or the correlated stagnation in US life expectancy to see how rich ‘the people’ truly are.