Is the UN to Blame for its Failures?

Joe Nye, the premier soft power theorist, defends the United Nations from its critics from the Right, arguing they don’t understand the value of international legitimacy.

Joe Nye, the premier soft power theorist, defends the United Nations from its critics from the Right, arguing they don’t understand the value of international legitimacy.

After the failure of the League of Nations in the 1930’s, the UN was designed to have the Security Council’s permanent members act as policemen to enforce collective security. When the great powers agreed, the UN had impressive hard power, as demonstrated in the Korean War and the first Gulf War. But such cases were exceptional. During the Cold War, the Council was divided. As one expert put it, its permanent members’ veto was designed to be like a fuse box in an electrical system: better that the lights go out than that the house burn down.

Well . . . Security Council action in Korea was possible only because the Soviets boycotted and the Chinese seat was occupied by Taiwan. The First Gulf War was indeed fought pursuant to Resolution 678, with the abstention of China and the reluctant acquiescence of the collapsing Soviet government. Regardless, the fighting was done by coalitions of the willing.

But, yes, the idea behind the Security Council was to give the then-great powers a mechanism for working together when they chose without the institution collapsing when they disagreed.

Despite those limits, the UN has considerable soft power that arises from its ability to legitimize the actions of states, particularly regarding the use of force. People do not live wholly by the word, but neither do they live solely by the sword. For example, the UN could not prevent the invasion of Iraq in 2003, but the absence of its imprimatur greatly raised the costs to the American and British governments.

Absolutely. Of course, that’s as much an argument against the UN as for.

Some American leaders then tried to de-legitimize the UN and called for an alternative alliance of democracies. But they missed the point: Iraq policy had divided allied democracies, and, with its universal membership, the UN remained an important source of legitimacy in the eyes of most of the world.

It’s true that an alliance of democracies wouldn’t have worked any better in 2003 than the UN. That doesn’t, however, make it a bad idea.

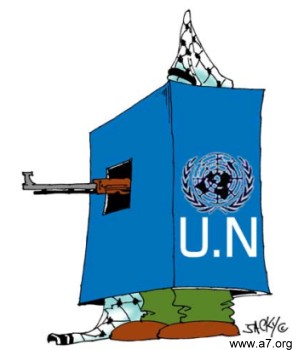

The greatest damage to the UN’s legitimacy has been self-inflicted. For example, in recent years the internal bloc politics among its member states produced a Human Rights Council with little interest in fair procedures or the advance of human rights. Likewise, administrative inefficiency has led to poor performance of high-profile efforts like the oil-for-food program.

This rather strongly understates the UN’s inherent corruption. It’s a creature of its member states and far too many of them don’t share modern views of propriety.

In the aftermath of the 2006 Israel-Lebanon War, states turned once again to UN peacekeepers, as they have in dealing with the problems in the Congo and Darfur. But, while there are currently more than 100,000 troops from various nations serving in UN peacekeeping missions around the world, member states are not providing adequate resources, training, and equipment. Moreover, governments have found ways to delay effective international action, as has been the case in Sudan. It remains to be see whether China, concerned that its oil trade with Sudan might jeopardize the 2008 Olympics, will decide to exert more pressure.

Similarly, while the General Assembly may have agreed that states have a “responsibility to protect,” many members agreed only in a very limited sense. Many developing countries, in particular, remain jealous of their sovereignty and fear that the new principle could infringe it. For example, in the aftermath of the recent government crackdown in Myanmar (Burma), the Secretary General was able to send a representative to the country, but with powers limited to reporting and attempted mediation. That may be enough to influence some governments, but the Burmese junta recently expelled the UN’s representative after he warned of “a deteriorating humanitarian situation.”

That would seem to mitigate against the soft power argument, no? There’s no doubt that the UN imprimatur can add legitimacy to collective action. But Member states routinely ignore this soft power when it conflicts with their interests.

In such cases, it makes no sense to blame the UN. Soft power is real, but it has its limits. The fault lies not with the UN, but with the lack of consensus among member states.

But the lack of consensus among member states goes to the essence of the UN project. Its entire purpose is to build international consensus. Sixty plus years in, it’s no closer to achieving that than at the founding.

Ezra Klein takes on Nye’s piece from the Left,

He’s right to distinguish the institution’s hard and soft power, and right to note that its paralysis isn’t endemic to the body but the result of disagreement amongst member states, but that’s exactly what the so-called “realists” loathe. They don’t think American power should be constrained by disagreements with other states. That’s their point.

While Ezra’s right that “voluntarily restraining our power works to further our overarching interests,” it’s an almost impossible sell in the context of an institution in which the voice of the United States counts the same as that of Burundi.

“an institution in which the voice of the United States counts the same as that of Burundi.”

Oh, get real. Our voice counts the same as Burundi in the General Assembly, which is not the body that has any ability to restrain our power, or to do much of anything. Our voice is extremely powerful in the Security Council, given that it can do nothing without our assent.

“Its entire purpose is to build international consensus.”

Actually, not really. Its entire purpose, or at least its core purpose, is to provide a forum for diplomacy that could reduce the risks of another World War. That was the central motivation for the LON after WWI and the even more pressing motivation for the UN after WWII.

Consensus is great. But the most important goal is to give antagonistic powers every avenue possible for a peaceful resolution of their conflicts.

The world’s nations are not democratic, by and large– at least half have some form of dictatorship, or total control by way of adding religion to government. This means that at the government level we have antithetical, amoral or immoral voices working against the common good within the UN much of the time, and constantly focused on how to capture more money– from the US–legally, or not.

To give up any part of our sovereignty to such a gang is playing the fool. To fund this mess is also foolish, in my opinion. Corruption in the UN has become an art form, it seems.

Of what good was the UN to us in the case of Iraq? Tell me what good it has served in the GWOT. Of what good has it been in the case of Iran and its thrust for nuclear weapons? Of what good would it be if China decided to invade Taiwan, or Russia went into one of its former nations? My take is that it would be zero. Huge discussions, votes and sanctions in the UN Security Council would not change the facts on the ground, even if they had a quorum on the issue.

We delude ourselves that UN approval of our actions conveys legitimacy, when the members themselves are not actually legitimate, in the sense of being rational, relatively altruistic players, and democratic in their very nature.

We delude ourselves that having such a forum prevents war. It didn’t prevent the Korean War; it didn’t prevent the Vietnam War, and it didn’t prevent the first or second Gulf Wars. The UN most certainly does not prevent a nuclear war, if it comes to a major conflict between two nuclear powers. The power to halt such a conflict, by diplomacy and threats of retaliation, comes from each major nation acting in its own interest and banding together at the time. Normal diplomatic channels serve this end quite well, and they are not cluttered with tens and hundreds of pipsqueak diplomats from amoral nations that want a say, or want a delay for their own benefit.

The UN is a failure, and its participants are at fault, including the US, for giving their trust to gangsters and thieves for handling massive sums of money that simply disappear without adequate accounting.

The UN wants to extend its control over the US, if my reading of their proposed gun control measures and their LOST treaty are any indication.

I vote NO!