Minority Power in the Senate

Senator Romney and the latest edition of the senatorial pro-filibuster op/ed.

Senator Manchin has tread this ground as has Senator Sinema, and now it is Senator Romney’s turn to add to the list of pro-fillibuster essays published in a major American newspaper. His entry was, like the others, in WaPo and was published last weekend: Filibuster or bust: Maintaining the minority’s power in the Senate is critical.

To the column:

The United States Senate is one of our vital democratic institutions. Since shortly after our nation’s founding, a single senator has been permitted to speak indefinitely, delaying and possibly impairing legislation favored by the majority, even if that senator were in the minority.

I suppose it really depends on the definition of “shortly” as it took multiple decades for what we now understand as the filibuster to evolve (indeed, I think that “shortly” makes it sound a lot more immediate than was the case). But regardless of how quickly, or not, the tactic evolved casting it simply as a normal part of legislating in the Senate obscures the reality of what the mechanism was used for for most of its history. I would refer readers to my review of Adm Jentleson’s book, Kill Switch (and, indeed, to the book itself) to examine the problem with blithely suggesting that the filibuster is just some early add-on to Senate procedure (and to pretend like it was used for normal legislation for most of its existence).

Allow me to quote myself in this regard:

According to Jentleson, “From the end of Reconstruction in 1877 until 1964, the only bills that were stopped by filibusters were civil rights bills” (108). Indeed, despite a lot of mythologizing (that continues to the present day) about deliberation and the rights of Senators to be heard, the filibuster has its origins as a tool for squelching the rights of the Black minority in the United States. This is not hyperbole and paves the way for some serious reevaluation of the procedure from 1964 back.

The current story of the filibuster is a more recent one linked to simple obstruction by the minority party, more often by the Republicans than by the Democrats. This stands to reason from a partisan POV, as “The modern Senate creates a structural advantage for conservatives because its rules have evolved to make it incredibly easy to stop legislation” (124).

But we can start with the title of the op/ed (specifically, “Maintaining the minority’s power in the Senate is critical”)and its expansion in the text of the piece. Let me be direct: the structure of the Senate is such that the minority of the country is over-represented Period. Full stop. Whether this is good, bad, or indifferent from a normative POV is its own debate, but it is nonetheless true. The very existence of a chamber that gives each state two seats regardless of their populations will, by definition, give a minority of voters more power than the majority. This is especially true when the parties are polarized and aligned as they currently are. This is zero empirical doubt that urban voters are under-represented in the Senate.

Indeed, I will note again this piece in NY Magazine: Republican Senators Haven’t Represented a Majority of Voters Since 1996.

And for the bajillioneth time, this is nonsense:

The power given to the minority and the resulting requirement for political consensus are among the Senate’s defining features.

This sounds great, but it is not true. It is wholly possible that Romney believes this (because it appears a lot of Americans believe it), but there is no evidence that super-majority requirements lead to consensus and compromise. Instead, they just give the minority a veto, plain and simple.

I have written extensively on this before, to name three occasions:

Back to Romney:

Note that in our federal government, empowerment of the minority is established in just one institution: the Senate. The majority decides in the House; the majority decides in the Supreme Court; and the president is a majority of one. Only in the Senate does the minority restrain the power of the majority.

Note that, as already noted, the Senate empowers the minority via seat allocation without the filibuster, so if that is his concern, the very existence of the chamber addresses minority representation. Note, too, that the Supreme Court is currently dominated by appointments from presidents who can win office with a minority of popular support, and was confirmed by the minority-dominated Senate. That they require 5 votes out of 9 does not make them exemplars of majority rule (and let’s not forget it takes only 4 of 9 to hear a case).

We are actually a lot closer to actual minority rule than we are to needing special protections for political minorities.

That a minority should be afforded such political power is a critical element of the institution. For a law to pass in the Senate, it must appeal to senators in both parties. This virtually ensures that a bill did not originate from the extreme wing of either party and will thus best represent the interests of a broad swath of Americans.

First, and I repeat myself, the Senate empowers the minority via seat allocation

Second, there is no good argument for why legislation needs support from both parties. There is a reason, after all, that the parties exist. They. Don’t. Agree. On. Policy. As I have noted before, and keep referring to, the period in US history during which bipartisanship was seen as normal was not because of institutional design, or that we used to be more prone to compromise, but because of the peculiar effects of Reconstruction on the party system.

Romney cleaves heavily to the bipartisanship myth:

The Senate’s minority empowerment has meant that our nation’s policies inevitably tack toward the center. As then-Sen. Joe Biden said in 2005: “At its core, the filibuster is not about stopping a nominee or a bill, it’s all about compromise and moderation.”

But this is not true and it wasn’t true when Biden said it in 2005.

Consider how different the Senate would be without the filibuster.

That’s easy: the majority would be able to pass legislation without playing games like reconciliation.

Whenever one party replaced the other as the majority, tax and spending priorities, safety net programs, national security policy and cultural interests would careen from one extreme to the other, creating uncertainty and unpredictability for families, employers and our partners around the world.

No, it would create a situation in which if a party could win the majority of the seats, it could then govern, which is the way that representative democracy is supposed to work. Such a circumstance also creates more clarity for voters so that they can see what happens when one party is allowed to govern and they could then respond accordingly at the ballot box.

The reality is that biasing the system to inaction favors Republican policy preferences and so that is why the GOP favors it. This is not some valuable mechanism that creates bipartisan compromise.

And look, if one wants to make an argument that national legislation should both have to be acceptable to the majority of the population through the House and the majority of the states through the Senate, that’s at least an operative theory of concurrent majorities. I think there are various flaws with the argument that I will not get into here, but such a theory does not also require a minority veto in the Senate.

The Democrats’ latest justification for eliminating the filibuster is Republicans’ unwillingness to pass partisan election-reform legislation. Democrats have filed these bills numerous times over numerous years, almost always without seeking Republican involvement in drafting them. Anytime legislation is crafted and sponsored exclusively by one party, it is obviously an unserious partisan effort aimed at messaging and energizing that party’s base. Any serious legislative effort is negotiated and sponsored by both parties.

This is nonsensical. Again, we have two parties for a reason, and that reason is that we do not all agree on policy, and that is okay. It is why we have elections.

Finally, consider a more immediate implication of eliminating the filibuster. There is a reasonable chance that Republicans could win both houses of Congress in the next election cycle and, further, that Donald Trump could be elected president once again in 2024. Have Democrats thought through what it would mean for them for Trump to be entirely unrestrained, with the Democratic minority having no power whatsoever? If Democrats eliminate the filibuster now, they — and the country — may soon regret it very much.

This is a frequent argument, but it is flawed.

Again: the GOP’s legislative agenda is more about blocking change and confirming judges. The legislative filibuster serves that agenda quite well. Meanwhile, Democrats want to pass legislation. The legislative filibuster makes that all the more difficult. So which party should want the legislative filibuster?

Note that the main reason the not-yet-passed big social spending bill is such a big bill is that it has to be a huge bill due to having to go the reconciliation route. They cannot break it down into more palatable pieces (that would also make messaging easier) because they know that even if they have 50+ votes for certain pieces, the filibuster would block them (and that can’t repeatedly use the reconciliation process).

So, for Democrats to be successful legislatively, they have to have control of the House, 60 votes in the Senate, and the presidency. (Or, at least 50+ votes and reconciliation for a handful of bills).

But, for Republicans to be successful (for the most part) they really only need 41 votes in the Senate. And for their judicial nomination wants, they only need 50+the veep there are well (or 51 or more to block a Democratic president from getting a vote on a nominee). Also, since their main policy goals are linked to taxes, the reconciliation route works to their advantage because it is linked to the budget (while things like the minimum wage or voting rights can’t go the reconciliation route).

Note, too that the legislative cycle is two years and only two years (and, really, less than two years because of the need to campaign, both for re-nomination and re-election). This, again, rebounds to the party that wants to block. Slowing the legislative process is easier than speeding it up.

All of this is about the probabilities of controlling institutions (House, Senate, White House) and what the party’s goals are. The GOP’s policy goals are fare more amendable to the filibuster than are the Democrat’s.

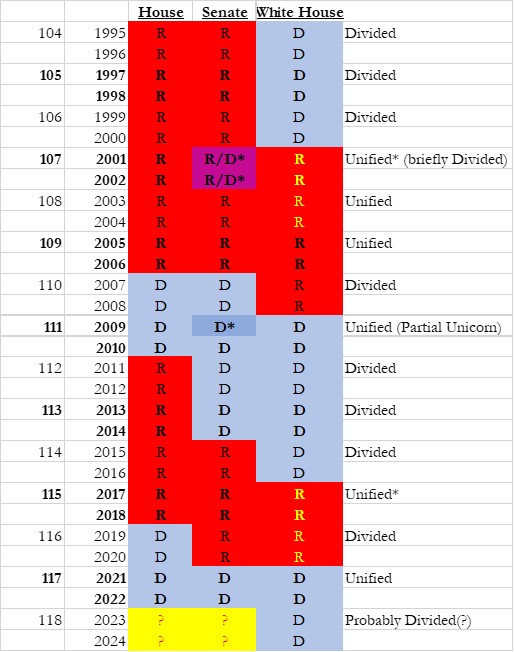

Some context to consider. The table shows partisan control of the House, Senate, and White House since the 1994 election (the “Republican Revolution”) and the start of the current party era. The left hand number is which Congress was in session (a Congress lasts only two years). The yellow Rs represent Republican presidencies that were the result of a popular vote/electoral vote inversion (which is also why Unified has an asterisk). The purple R/D* are cases in which control of the chamber went back and forth for various reasons. The darker blue D* is indicative of the unicorn that is 60 votes (which the Democrats had for part of 2009.

Divided government (8 congresses plus a likely additional one in 118th) was more prevalent than unified government (6 cases) during this period. Unified Republican governments (4) have outnumbered Democratic ones (2)–of course, if we had a national popular vote instead of the Electoral College, the number of unified Republican governments would have been one (the 109th)–all other things being equal.

So, the strategic choice for Democratic Party is this: does it wish to maintain the power to block Republican legislation during periods of united government or should it use the power to govern when it has it (which would require getting rid of the filibuster)? There are arguments for both positions, but if, as I argue above, the Democrats actually want to govern and the Republicans want to block change, then the filibuster works more to the Republican’s advantage than it does to the Democrat’s–especially when we consider that the deck is stacked against Democratic unified government.

All I can say is bravo.

The instant Republicans take back the Senate they’ll kill the filibuster and that jellyfish Romney will support the move.

Filibuster and Electoral College. Two things that need to go the way of the dinosaur.

Perhaps the United States should adopt a parliamentary system. Its rare for a governing party in a parliamentary system to represent over 50% of the voters. In fact they usually need only about 40% of the vote to gain a majority of seats, though even that is often hard to acquire leading to coalition gov’ts — however the parliamentary mechanism allows for actual governing even with less than 50% of the voters agreeing on a single party. Meanwhile, the American system seems designed to force people with widely differing political wishes into only two parties, and to then make actually passing legislation extremely hard. Its hard to see how that can be anything but a disaster waiting to happen (or in fact slowly happening).

Has the former governor of Massachussets considered any GQP senate majority leader can brush away the filibuster if he wanted to? Or that if they love the filibuster so much, the GQP can reinstate it when they take the majority?

Perhaps Republicans should take some of that donor money and buy themselves some agency.

@Michael Reynolds:

I don’t see that happening under McConnell. He’s had plenty of chances and has never opted for that option (even when Trump was putting significant pressure on him to do it).

Likewise, it would only be a useful option with a Republican in the Whitehouse. Doing it under Biden makes no sense as they would still have to deal with the veto.

@George:..Perhaps the United States should adopt a parliamentary system.

Perhaps.

Which of the two methods in Article V allowing for changing the United States Constitution do you think would facilitate the creation of a United States Parliament?

Looks like …no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate. is what I think is called boilerplate and can not be changed other than changing the number of Senators alloted to each state as long as all states have the same number of Senators.

How would this work in a United States Parliament?

@Mister Bluster:

I wasn’t seriously suggesting it could happen, I was mainly pointing out that its vital that an elected gov’t be able to legislate, even if it doesn’t represent 50% of the popular vote, let alone the 60% the filibuster rule seems to suggest.

Which is becoming less and less true due to sophisticated gerrymandering. Not as bad as the Senate, but still. I think I read something recently that the new Congressional map proposed for North Carolina will likely produce 11 Republican and three Democratic Representatives from a nearly 50-50 vote.

@mattbernius:

McConnell is not his own master, not since Trump. He’ll do whatever the ranting orange baboon tells him to do because push come to shove GOP Senators will fall in line with Trump, not Mitch.

@Mister Bluster:

While I don’t understand how you wouldn’t be able to change the senate if you changed the constitution but you could do what they did in the UK with the house of lords. Just strip it of any meaningful power.

They can have the power to hold up confirmations or legislation for thirty days provided that there is floor debate going on, and then it has to go up for a vote. Otherwise they can pass legislation and send it to the house, do their investigative thing, and pass proclamations to make it stamp day.

@Rick DeMent:

Tell us which 34 states will vote to amend the Constitution? There aren’t 34, therefore the Senate will remain what it is, subject to the senate itself changing the rules. It is not only the small states that would vote against it, but also large states like TX and FLA due to domination by the R party.

Even the northern New England states that are blue or purple won’t support such a change, even when Dems control the legislatures.

@Michael Cain: There are major representation problems for the House. I just didn’t want to get into them here.

My train of thought just now suggests the Constitution does not mandate any type of state government. Most states, though are like a miniature version of the federal government, complete with separation of powers.

I wonder if a state could change its government to a parliamentary system. Probably they’d have to massively amend or replace their constitution.

@Kathy:

The states can organize their government the way they want. While each state has a governor and a legislature, there are unicameral and bicameral legislatures, with some meeting only every 2 years, some state have governor’s councils that have responsibility approving judges, cabinet officials etc. So yes, a state could organize itself with a parliamentary form of government.

The way I read this only a State can consent to being deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate. The United States Senate has no role other than to accept a State’s action.

Not sure how this consent would come about. An individual State legislature pass bills in both chambers (unicameral in Nebraska) by simple 50%+1 majority? Supermajority of 2/3 ? 3/4? then signed by the Executive?

Crazy idea. How about a State (Illinois for instance) consent to the unequal suffrage that 3 United States Senate Seats would bring about.

Never mind. The other 49, two US Senate seats States would have to consent also as they would then all have unequal suffrage in the US Senate compared to the Land of Lincoln.

@Kathy:

Article IV, section 4 guarantees the states a Republican form of government, so gerrymandering to insure that Republican representatives outnumber Democrats is not only acceptable but Constitutionally mandated.

@Sleeping Dog: At least implicitly, the Constitution seems to require voting for representatives in a legislative body of some sort, and an “executive authority” in the 17th Amendment to appoint replacement Senators. A number of federal statutes assign some responsibilities explicitly to a “governor”. A prime minister would probably be acceptable for either.

@Michael Reynolds:

History doesn’t bear that out when it comes to the filibuster:

https://www.politico.com/story/2018/06/27/mitch-mcconnell-filibuster-trump-678817

https://www.newsweek.com/trump-calls-mitch-mcconnell-knucklehead-not-eliminating-filibuster-1611095

@mattbernius:

I don’t recall any major legislation the GQP tried to pass during Benito’s first two years, other than a repeal of the ACA, which they eventually tried to do on reconciliation. I recall El Cheeto whining about “60 votes,” as though he couldn’t recall or spell filibuster*, and McConnell keeping a stern face and wagging his finger “no.” But I don’t recall what it was about.

as to the ACA repeal, I recall the late Senator McCain arguing it should be done through “regular order,” meaning as a bill itself subject to a vote. I don’t recall he opposed the filibuster.

*Maybe it sounds as though it’s not a real word. Or maybe like a dirty one, as in “Oh, go filibuster yourself!”

@Kathy:

As memory serves it was all about the border wall and immigration.

@matt bernius: Except, they didn’t even have 50 votes, so I take that as McConnell being able to count to 50, but not able to get Trump to count to 50.

In 2012 Romney pretty well demonstrated he was the biggest liar to ever run for president, a title Trump took away from him in 2016. This op-ed certainly did no damage to his reputation as the second biggest liar in the Republican Party, and therefore likely in the world.

@Kathy: So I wrote up a lot about this…

…and then I ran into the Constitution.

So, my interpretation of what you’re suggesting is that US Senate seat apportionment by done in a parliamentary manner. And by “parliamentary manner”, I take you to mean “chosen by the national party, according to some set of allocation rules”. This is completely unconstitutional.

Amendment 17 explicitly requires that the votes for the Senator come from the represented state. This means there’s no room for an intermediating entity like a political party. Senate.gov actually provides a whole history lesson on the subject, most of which I didn’t know: https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Direct_Election_Senators.htm. Changing the method of choosing US Senators requires a Constitutional Amendment; it’s not up to the State. (Same with the House of Reps.)

If you were asking about the internal government of a state, then yeah, that’s 100% the state’s prerogative, but it kinda only matters to people who live in that state, or have some major tie to that state. Same reason we complain about CA’s governor-recall rules, but most of us don’t actually live there and can only pundit about it. The representation problems internal to states are a much smaller issue than the national problem, but we’re definitely already feeling the effects of the national polarization being reflected at the state level.

@David S.:

I meant the internal government of a state.

This is an absurdly dishonest claim made by supporters of the filibuster that can easily be tested against empirical evidence. Most US state legislatures operate on simply majority rule. To the best of my knowledge, ALL other democratic nations pass ordinary legislation by simply majority rule. Yet their laws don’t “careen from one extreme to the other” for the very good reason that most politicians won’t support extreme positions. Extreme positions are a good way to lose the next election. That’s why Bernie Sanders’ $6 trillion wish list has been hacked down to $1.75 trillion, with no guarantee even that will pass. That’s why nearly all the illegal immigrants Trump promised to deport are still in America.

Once political parties know they’ll be stuck with the consequences of their policy positions, they tend to become more circumspect about what they’ll try to accomplish in government. The filibuster is a kind of moral hazard, enticing the majority party in the House to pass wildly inflammatory bills knowing full well they’ll be killed by the minority party in the Senate. The presidential veto allows a party to indulge in similar performative irresponsibility when it controls both chambers. For that reason alone, both measures make for bad governance.

I kinda wish the Dems called their bluff when they were the minority early in the TFG era. “Go ahead and blow up the filibuster, Mitch. We dare you.”

@Ken_L:

Agreed. We saw, for example, that even using Reconciliation and with control of all three branches of government, the Republicans were not able to eliminate Obamacare/ACA.

Further, if the Senators were truely concerned about “Whenever one party replaced the other as the majority, tax and spending priorities, safety net programs, national security policy and cultural interests would careen from one extreme to the other” they would move to legislatively curtail executive power as this is exactly what happens today thanks to Executive Orders and Signing Statements.

@Sleeping Dog:

Sure, but you can say the same thing for changing the Senate in anyway, I’m talking about the idea that the Senate could ever be changed, even by constitutional amendment from a two seat per state institution. So if you buy into the idea that you can never change the Senate from being a two per state institution, you could deal with that by changing the powers an limiting their ability to obstruct. You would have to change the constitution in either case.