More on Social Policy and Comparisons

Mostly about how not to do it.

I have to confess that I made a mistake. That mistake was being sucked into reading Brett Stephens’ column in the NYT, Biden’s Plan Promises Permanent Decline. I mean, with that kind of prediction, how could I not be intrigued?

I will start with two legitimate points that Stephens makes.

First, he makes a common, and legitimate, conservative point that there may be unintended consequences and costs for these programs. This is undoubtedly true and is often a caution that prudent conservatives offer off up as a consideration about the limits of human reason and its limited ability to foresee the future. Of course, it is also often a seemingly wise admonition that has the result of nothing happening, which is often the conservative position to begin with. As such, it is often difficult to decide whether this proclivity to worry about the unforeseen is wisdom or just a handy excuse to forestall change. Although I will allow that regardless of motivation, it is a thought worthy of some level of consideration.

Second, he notes that once social services are expanded, taking them away will be very difficult for Republicans to accomplish down the road. This is certainly true (see, e.g., “repeal and replace” efforts and the ACA as a recent historical manifestation of this fact). But, it does raise a question that contradicts the thesis of the title (and of the piece): that these proposed changes are a net negative for the country. Why is it that changes that conservatives allege will lead to ruin (such as, in the past, Social Security, Medicare, and the ACA, to name three) end up not only not leading to ruin, but end up becoming so popular that getting rid of them becomes politically impossible?

Could it be that these predictions of doom are inaccurate?

To quote a former Republican President, “‘Fool me once, shame on…shame on you. Fool me—you can’t get fooled again!“

Setting aside the track record of conservative doom and gloom in these matter, let’s look at the content of Stephens’ column, which is an attempt to make some comparative points.

He starts with an anecdote:

Years ago, Alexis Tsipras, the party leader of Greece’s Coalition of the Radical Left, surprised me with a question. “Here in the United States,” the soon-to-be prime minister asked me over breakfast in New York, “why do you not have this phenomenon of passing money under the table?”

The subject was health care. Greece has a public health care system that, in theory, guarantees its citizens access to necessary medical care.

Practice, however, is another matter. Patients in Greek public hospitals, Tsipras explained, would first have to slip a doctor “an envelope with a certain amount of money” before they could expect to get treatment. The government, he added, underpaid its doctors and then looked the other way as they topped up their income with bribes.

Now, as a comparativist with some passing knowledge of Greek politics (although I am no expert), my first thought upon reading this was, “Greece has a known corruption problem, doesn’t it?”

Indeed it does.

I looked at Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index and noted that, in fact, Greece doesn’t score all that well, especially for a European democracy. Greece scored a 50/100, which ranked it 59 out of 180 cases. Indeed, it had improved its score by 14 points since 2012. So, Greece doesn’t score well in this realm now and it scored worse “years ago” (probably circa 2015, based on how it is described above).

For what it is worth, if you look at the CPI list, the US is tied for 25th (with Chile) with a score of 67. The number one slot is a tie between Denmark and New Zealand with a score of 88. Note they both have universal health care, as do almost all, if not all, of the countries that rank ahead of the US (there are a couple of cases I am not sure how to classify in that list). The average score for Western Europe and the EU is 66 (the highest regional average in the world).

So, while Stephens is right to note the following (the basic thesis of his piece), there is precisely zero usefulness in equating Greek problems with corruption to the presence of universal health care:

Take a close look at any country or locality in which the government offers allegedly free or highly subsidized goods and you’ll usually discover that there’s a catch.

But, of course, there is a catch (defined as some imperfection or cost) in any choice made. There is a “catch” for the current US system of health care, just as there is with any other system. There is a “catch” to full market solutions and a catch to government intervention in the market. Governance is about balancing the catches.

The true main problem with all of Stephens’ evidence is that he identifies a “catch” without asking whether the catch in his example is better, worse, or the same as the catches in the US.

He provides, for example, a golden oldie: wait times and universal health care:

In Britain, the National Health Service is a source of pride. Except that, even before the pandemic, one in six patients faced wait times of more than 18 weeks for routine treatment.

This one always gets trotted out, but first, note that the NHS is just one version of universal health care among many (and is almost certainly not the type that will come to the US if one ever does). But, here’s a catch that citizens of the UK don’t deal with: bankruptcies due to medical costs (to name one).

Beyond that, I would like to know a) what are wait times for similar procedures in the US? And, more importantly, b) what is the percentage of citizen access to comparable procedures across the two countries? (I would also like to know what wait times are in other systems, of which there are several different types across a host of countries to compare).

Above all else, in terms of slam-dunk, oh my gosh! kinds of stats, is noting that 16.7% (one in six) of patients face long waits supposed to be impressive?

He cites other examples:

France’s subsidized day care is, by all accounts, fantastic for working parents who get their children into it. Except there’s a perpetual shortage of slots. In Sweden, a raft of laws protects tenants from excessively high rent. Except wait times for apartments can be as long as 20 years.

Ok, maybe the shortages of slots and wait lists for apartments make those systems not worth pursuing. Or maybe there are fixes that are needed. But you can’t just assert these problems without trying to put in context what isn’t working in the US. In other words, is the US system of day care sufficiently superior to France’s for us to dismiss it as a model? Perhaps the answer is yes, but you can’t get there by just point to a single negative example of their system.

The entire column is made up of this kind of “argument.”

Look, I am not saying that everything we do in the US is horrible and that everyone else does it perfectly and all we have to do is be like X. But it is also true that there are successful social policies in other places that are worth closer examination. I am especially noting that it is poor rhetoric, and even worse social science, to point out a problem or two about something else without providing actual comparisons.

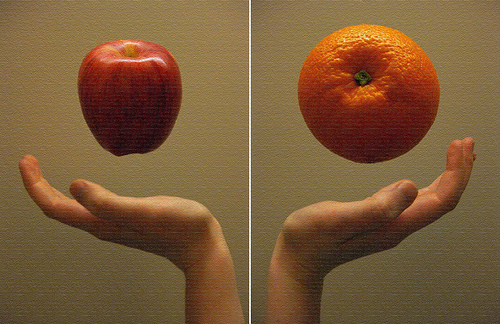

It may be true, for example, that the car you are thinking of buying gets worse gas mileage than you would like. But if the alternative is the old car with a busted transmission, the gas mileage issue becomes more than a manageable objection. I know that is a clearly extreme example, but the point is: it takes data from both sides of the comparison to allow for an actual assessment. Approaches like Stephens’ are intended to make the reader assume only the best about the US contetx while being turned off by his litany of problems in those places with all those terrible social programs.

All policies have up sides and down sides, and an honest assessment has to be willing to take it all into account.

And look, while it is clearly the case that I am sympathetic to increased spending on social policies of the type under discussion, I am more than amenable to a real evidence-based argument as to why we should, or should not, do X, Y, or Z.

Back to Stephens:

What will America get for the money? The progressive bet is that it will be things Americans like and want to keep, like universal pre-K and paid parental leave. Progressives also bet Americans won’t mind that the Jeff Bezoses and Elon Musks of the world will pay for all of it.

Maybe those bets will pay off. And conservatives would be foolish to dismiss the sheer political appeal of the progressive pitch. But before the U.S. takes this leap into a full-blown American social-welfare state, moderates in Congress like Senator Joe Manchin or Representative Jim Costa ought to ask: What’s the catch?

All well and good. But they should also ask what the catch is for not engaging in the spending. Stephens pretends like the status quo has no cost.

His conclusion, which circles back to the title is, well, drivel:

But investments like these, once made, are almost never reversed. The spending will become permanent. Beyond the gargantuan cost, Congress should think very hard about the real catch: transforming America into a kinder, gentler place of permanent decline.

He makes no case for “permanent decline” in the piece. None. In fact, the word only appears in this paragraph and in the title. He implies possible negative outcomes, but there is no systematic argument constructed.

I assume his point is that the sum total of all the bad things he has cherry-picked about other countries will lead to US decline, but he doesn’t actually make that case. That there is a catch for everything is not proof of decline.

The closet he comes is stuff like this:

The real catch is that massive government spending has hidden costs that are difficult to capture in numbers alone.

Take another look at Europe. Why does R&D spending in the European Union persistently lag that in the U.S., to say nothing of places like Japan and South Korea?

This is where I note that Japan and South both have universal healthcare and extensive social safety nets, especially Japan. As such, none of this makes sense in terms of staking out a coherent claim.

Ultimately, I feel like I have read some version of this column my entire life and I am to the point of being utterly tired out by the poor argumentation of it all.

One of the things that rarely gets mentioned is the cost of NOT making a change.

For example, homelessness. Virtually any proposal to deal with it will be subjected to a barrage of queries about how much it will cost, how the funds will be raised, etc.

All good questions, but all based on an assumption that to do nothing is cost-free.

But as with most problems, homelessness imposes a massive cost in terms of emergency services, and the decline of property values.

It can be conservatively estimated that the drop in property values in major urban areas adds up to billions of dollars yearly.

This is a tax, a hidden siphoning off of wealth from the property owners. Yet it is ignored when evaluating a proposed policy change.

Poor argumentation is what you resort to when you have nothing substantive to offer. Stephens is just attempting the scaremongering of “The liberals are cancelling the Dr. Seuss & Snow White you love.” – or – “Voting Democratic means you’ll have to eat lettuce every day.” He’s dressed his scaremongering in the trappings of a policy discussion, but it’s the same old BS.

Quite a coincidence. If we’re going to, as Stephens does, reduce all criticism to one data point, I came across a doozy today:

A 30-year-old American is three times more likely to die at that age than his or her European peers. In fact, Americans do worse at just about every age. To make matters more grim, the American disadvantage is growing over time.

Doesn’t that about trump it all?

He doesn’t think he needs to. “People increasingly pay collectively and efficiently for useful infrastructure instead of paying a la carte for expensive special services” is his idea of decline, which he thinks is obvious, and the fact that people tend to discover that they like infrastructure and wish to keep it makes it permanent.

None of these goobers ever seem to realize that the ‘arguments’ they muster could just as easily attack the original proposals for public schools, the US Army, non-toll roads, police and fire departments, water treatment plants, the New York subway, the internet, the US Mail, etc. If having those things is ‘decline’, then yes please, make it permanent.

I love the conservative obsession with the “unintended consequences” of liberal initiatives. Typically these are second order effects. Maybe you raise the top marginal income tax rate. As a first order effect you take in more money, but maybe less than expected because as a second order effect, tax avoidance increases.

But so many conservative initiatives don’t even produce their claimed first order effects. Trickle down has never worked. The Iraq war blew up the Middle East. The Afghan war didn’t get Bin Laden until Obama had to do it. Their voting laws don’t increase election security. And…and… sorry, I’m failing to come up with anything else they’ve actually done. (OK, this isn’t quite right because they lie about what they’re trying to do. Rich people did get their tax cuts, the Iraq war got Iraqi oil back on the market, Afghanistan got W reelected, and their silly voting laws are firing up the base.)

You take the author to task – and quite well – for not writing the article you wanted him to write. But I suspect he did indeed write the article he set out to write. Which has nothing to do with competent social science or a considered perspective on the trade-offs of various social policies.

This makes me think that your “mistake” wasn’t so much reading his column (annoying as it is), but rather spilling so much ink refuting it…..or rather, pleading for the column he didn’t write. Then again, maybe this was your way of atoning for the first mistake? Regardless, your mistake(s) is to my benefit, because I enjoy reading remote grumpy Dean – much more than I enjoy listening to local grumpy Dean talk about enrollment numbers

Look on the bright side, Steven. He didn’t make the other argument that usually accompanies the wait times objection. “People come here from countries with socialized medicine because we provide best health care in the world.”

Nobody bothers to look at how many Americans travel abroad in for health care. The answer? The outgoing traffic outnumbers the incoming traffic. And when surveyed, the majority of those Americans traveling abroad cite…cost.

I’m by no means opposed in principle to expanding social programs, but I think the gorilla looming in the corner is the failure to adequately plan how to pay for them.

That’s not a situation unique to the US. I’m loathe to keep referring back to France as an example, but in this instance it does shed light. There are some amazing social programs here, and they arguably and demonstrably improve the life circumstances of the entire population, but paying for them has historically been (and remains) a problem. The programs as a whole run in the red to the tune of billions of euros every year, but adjusting taxation (which is already onerous) to adequately underwrite their cost causes nasty consequences. On the other hand, proposing adjustments to control costs causes (caused) riots, so it’s a catch 22 that has evolved because the funding structure was essentially adequate when it was first proposed (shortly after WW2), but over time has become decidedly inadequate.

Should you ever wish a practical demonstration of the meaning of the phrase “howls of derisive laughter,” simply suggest to an European that whatever implementation of universal health insurance exists in their country be replaced by how America does it.

There is a reason he’s known as the Brettbug.

@DrDaveT: The arguments against federal control of ‘improvements’ goes back to at least the Eire Canal. The Jeffersonians refused to allow federal participation. So a compact of states built the waterway and NYCity surpassed Philadelphia.

Maybe this time will convince them, eh?

@Mimai:

🙂

@Chip Daniels:

Meh… not so much that doing nothing is cost free as that doing nothing imparts no direct and immediate costs to me. (And in passing, I would note that major cities such as Seattle and Portland, OR have amazing homelessness problems that don’t seem to have impacted property values to any great degree. It may depend on how you manage the homelessness–diverting it to freeway medians, overpasses, etc.)

@Kurtz: While I was in Korea, I had the chance to read an advertisement for medical tourism to Jeju Island–a farming and resort area off the coast–promising American-trained doctors working in state-of-the-art hospitals with extended recovery opportunities at a resort hotel.

The target audience of the ad was American HMOs and the payoff was that the fee for service in Korea was less than in-house treatment at the HMOs own hospital–including the extended recovery, which is frequently an out-patient service here.

Yes, Brett Stephens is talking nonsense, but it’s no different than the nonsense conservatives peddled for many decades. Conservatives are always wrong. Always. Everything from freaking out over Elvis Presley’s hips to trickle down economics, they are never right. The intellectual bankruptcy of American conservatism, going back at least to Goldwater and Reagan, is the reason the GOP was so easily diverted by the Tea Party and then taken over completely by lunatics.

Ideally we’d have some genuine intellectual conflict between Right and Left because I don’t entirely trust the Left. But after decades of conservatives being consistently wrong on everything from social justice to economics to foreign policy, the remaining political battles are not between Left and Right but between sane and crazy.

Picking at one particular part, while agreeing with much of what you said – health care frustrates me because the plural of anecdotes is not data, but those of us who have lived in or who have family in countries with universal health care are pretty familiar with the effect rationing has on them. It’s still rationing in the US, just based on money and employment instead of the funding for a province, postal code, or health district.

In our case: My Canadian mother in law waited 13 months for an oncologist, and a further 6 months for a procedure. When they went to execute the procedure, they determined that that they were just barely too late to save her life – that particular cancer is very treatable (nicknamed “Jellybelly”) if it’s caught in time. She died two years later. It took 48 hours for my sister in law, a professor in the US on a state-funded health plan, to see an oncologist and less than a week for exploratory checkout. Is that data? No. But my kids would really like to have their grandmother back.

Canadian grandmother wasn’t allowed to stay overnight in the hospital after her third heart attack, because she was over 75, and they told her she was past her sell-by-date. They wouldn’t approve further heart medications for her. She died four months later of a sudden heart attack.

Canadian father in law was taken to the hospital for a malaria relapse. The “hospital” had 21 beds and one doctor – not one at a time, not one per shift, one. In a stroke of luck, though, he’d just immigrated from a country with significant malaria problems, so he knew something about it. He’s still alive, and happy that at 75, he was eligible for a COVID vaccine, since his older sibling was told that at 77, they were saving the shots for people who had more life to live.

Had a friend told that her compound fracture wasn’t severe enough to rate weekend ambulance service in the UK, but they’d be happy to pick her up on Monday.

@Gawaine:

There are several public healthcare systems all over the world. Not all work equally well, or equally poorly. The thing is to see how they work, how they adapt, or can be adapted, to one’s country, and then implement it.

Mexico’s system is a mishmash of agencies at various levels, mostly state and federal. Where you get care depends on whether you work in the private sector, the federal government, the state government, the informal/underground economy.

There’s also a private system, ranging from walk-up clinics attached to discount pharmacies, to doctors who have their own offices and have deals with private hospitals to admit patients. This also includes charitable clinics and hospitals.

I can tell you little of the public system, because I’ve never used (though I do pay for it through payroll deductions). I know people who have, and they had few complaints about the quality of their care. There are wait times, and often shortages of medications.

@Gawaine: American here. When I needed to see an orthopedist for a knee injury, I had to wait six weeks (this was about 25 years ago, with private employer insurance). In 2019, I had three close family members who all needed surgery, two of them for cancer. With three different types of insurance (employer, Medicare, and Tricare), and living in three different states, they all to wait 3-6 months between diagnosis and the scheduled surgery. On the other hand, when my husband went to the ER for heart problems about 15 years ago, he was scheduled for surgery the next day.

So I don’t think it’s universal in the US that you don’t have wait times, even when insured.

@Monala: @Gawaine:

Oh yes, and in the last decade, my daughter got referrals from her pediatrician for ADHD testing and allergy testing. Again, I have employer insurance. In both cases, it took four months to get appointments with a behavioral psychologist and allergist.

American here. My wife has mental health issues that require prescription drugs from a psychiatrist. Her psychiatrist retired. Both our insurance company and her primary doctor say it’s up to her to find a new psychiatrist, and we can’t find one accepting new patients within 50 miles. We found one a bit further than that, but she can’t get an appointment for 3 months. Her prescriptions are legally limited to 30 days at a time.

We live in a mid-size American city.

You want to know panic and rage? Watch your wife lose access to the medications that keep her sane, while apparently no one thinks it’s their responsibility in our system to even TRY to help. We’re on our own, trying to figure out how to best stretch out the remaining pills because we don’t have a new 30-day prescription for something she’s been on for over a decade.

F*** the US system.

@Monala: Yet another anecdote point. In February, my hepatologist needed to reschedule my appointment. Next available date: May. Fast forwarding to May, the clinic forgot to remind me of when my appointment call was scheduled, so I was unable to answer the phone when the call came. It would have been nice to have been reminded because then, I would have rescheduled, but it turned out not to matter because the next available time for a call is in August.