Notes on Discharge Petitions

Some notes on House process and how it relates to recent and ongoing political news.

The reopening of the federal government has included the swearing in of the newest member of the US House of Representatives, Adelita Grijalva, and therefore the last signature needed for a discharge petition regarding a bill to disclose more information on the Epstein matter, as James Joyner noted last week. A vote on that discharge petition in the House is scheduled for tomorrow. And, in a late-night move last night, Trump has now endorsed the release of the files. How much of this is to avoid embarrassment, and how much is because new investigations that he has ordered will eventually block the release of the files, remains to be seen.

I do think that this process is a useful example of how scheduling in the House, in particular, is a key power of majority leadership and the lengths to which those outside of leadership have to go to get a bill to the floor.* A discharge petition allows a numerical majority of House members (in this case, a coalition of mostly Democrats and some Republicans) to force leadership to put a piece of legislation on the floor for debate and a vote when leadership does not wish to do so.

It is worth noting that of the four Republicans who signed on with the Democrats are Nancy Mace (she of the Miss Congeniality Award), Marjorie Taylor (or is that “Traitor”?) Greene, and Lauren Boebert (whom Trump took into the Situation Room to try and convince her to change he vote). Politics, as they say, makes for strange bedfellows. The fourth is Thomas Massie, who co-authored the petition, and was personally attacked by Trump on social media for remarrying about a year after his wife died.

For a more detailed understanding and context, I would point readers to Sarah Binder’s** Brookings piece from 2023 for details on the procedure: Don’t count on the House discharge rule to raise the debt limit.

The discharge rule dates from the 1910 revolt against House Speaker Joseph Cannon (R-IL). Frustrated by Czar Cannon’s tight-fisted control of the House, Democrats and Progressive Republicans fought for a rule that would allow a majority to bring bills to the floor that were bottled up in committee, circumventing committee and party leaders. The House has tweaked the rule a few times, but its purpose remains unchanged: If a majority can meet the rule’s strict requirements, it can force a vote to discharge a measure that might otherwise not see the light of day.

In simple terms, most bills have to go through the committee process and then are placed on the legislative calendar, but to escape the calendar typically requires a special rule created via the Rules Committee to actually make it to the floor for a vote. (This is a bare bones description of a much more complex process.)

One of the reasons that I keep focusing on how important is it to be the majority party in the House (and why being the Speaker is huge) is that majority leadership controls the Rules Committee and therefore what bills get voted on or not. This is why I keep harping on the fact that if the majority party does not want a matter taken up, it won’t be in the House in particular.

The Epstein files discharge petition is driven mostly by the minority party, but it requires a handful of Republican votes to proceed. This is the building of a legislative coalition to get action via majority will (numerically) as opposed to something a minority of members could do alone.

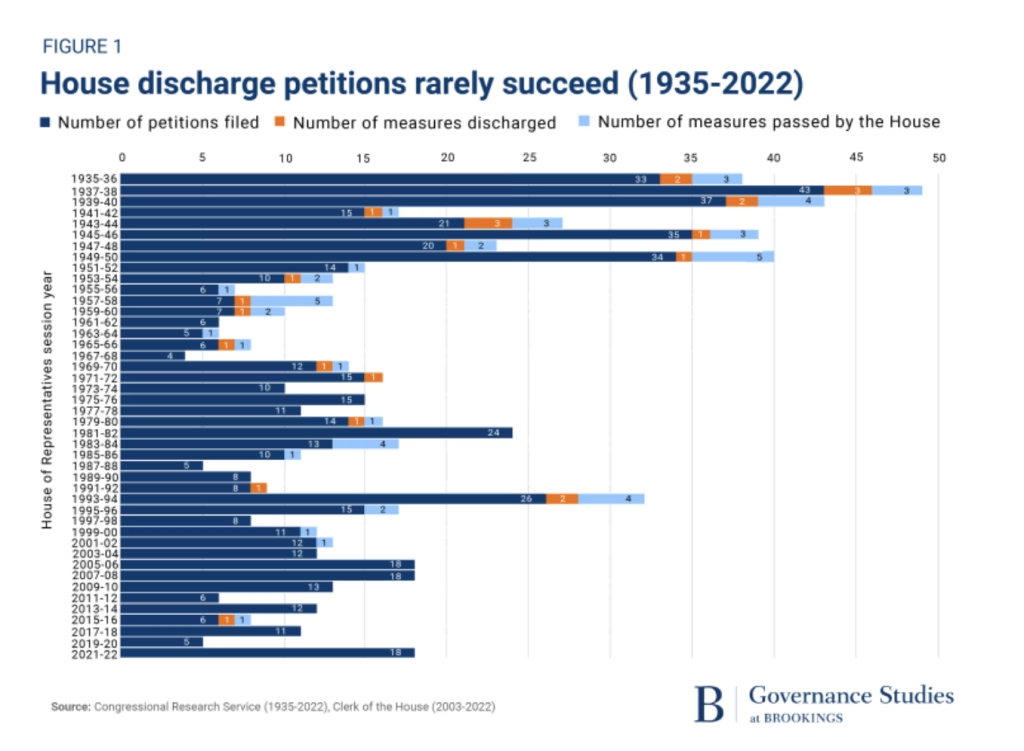

Here is a chart of attempted and successful discharge petitions (from the Binder piece). Note the poor success rate.

As it pertains to the discharge petition in the news, I would point readers to Jonathan Bernstein in terms of understanding what else could happen even after the discharge petition acquired the requisite signatures. Note that this was written last week, during which time Trump was still opposed to the files being released.

I’ve been saying here and elsewhere that reaching the magic 218 on the House discharge petition was mainly about internal House politics. Once they hit 218 – which the House did on Wednesday – that would appear to force a House vote, but in fact there appear to be a number of procedural options available to Speaker Mike Johnson to delay any vote for quite some time. Then even if it does get a vote (and win) it’s just an ordinary bill, which means it goes to the Senate, which can just ignore it. Or, if does come to the Senate floor for a vote, it would need to defeat a filibuster, which means 60 votes in a 53-47 Republican-majority chamber.

There’s more. Even if it has 60 votes, Senators could still add a poison pill amendment to it that might kill it in that chamber or back in the House. Or just any amendment at all to it, which would send it back to the House, where the Speaker could then block it from reaching the House floor. And if all that fails, Donald Trump would presumably veto the bill.

I bring all of this up to provide basic information on the process, and to note that just getting the final signature on the petition did not mean that the Epstein files will be released (as it seems some people think is the case). Trump’s TACOing of the situation may mean that some items are released, but again, if DOJ opens up new investigations, as Trump has ordered, what can be released is up in the air.

I also think all of this is worth contemplating for anyone who wants some insight into the legislative process. The proposed legislation (which is what the request to release the files is) is just a pretty straightforward action, and note how convoluted and complicated it is. The legislative process becomes substantially more complex the more complex a given piece of legislation is. And, also, it should help provide a little insight into why it is essentially impossible for a minority of Representatives to get a bill out of the House that the majority opposes.

I would stress something that may well be obvious, but is worth underscoring: while the discharge petition is mainly being driven, in terms of signatures, by the minority party (i.e., the Democrats), it still required the creation of a coalition between those Democrats and a very specific faction of the GOP that we usually associate with QAnon/fringe of the party (Boebert and MTG), an increasinlg vocal toublemaker (Nancy Mace), and a more libertarian-leaning type (Massie).

Note, too, that this is a request to discharge a specific bill, H.Res.581, from the Rules Committee. I expect that some people think that the petition is to discharge the Epstein Files, rather than to discharge H.Res.581.

While it now seems fairly likely that the legislation will pass and be signed, the real issue will be: what will actually be released and when?

Meanwhile, it just goes to show how one thing follows from another, and how the news cycle flows: if the government were still shut down, the tranche of e-mails from the House Oversight Committee would still be sitting on someone’s computer, and the last signature on the Discharge Petition would still be pending.

*Getting a bill to the floor means getting it out of committee, where it may be residing, or off the legislative calendar (basically a list of bills that have been reported out of committee), where it may be stuck. On the floor, there is a limited amount of time to debate (make speeches) and to amend the bill before a final vote. The time and parameters for amendment are dictated by a rule attached to the bill by the Rules Committee that dictates those factors. The conditions for floor action are not the same for every bill, and the rule can very much shape what kind of outcome is possible. Of course, the more complicated the legislation, the more things like amendment parameters can matter.

Legislating is a tad more complicated than School House Rock makes it sound, shall we say.

**Binder is an expert on Congressional procedure.

I seem to recall that if the Senate changes it — assume, for the moment, in a way the House majority that passed it doesn’t object to — there’s some form of privileged motion that can be made to concur with the Senate changes. If I’m remembering correctly, there’s no way for the Speaker to block such a motion and the required vote.

@Michael Cain: I believe that is correct.

And Walter Mondale isn’t around any more.

@Kathy: My state, like many in the US, has a part-time legislature. Many members forget some of the rules (and some never learn them). I had to learn all of them. One of my jobs was working committee meetings. Staff sat at the table during committee meetings, at the right hand of the chairman. Most of what we did was call the roll for votes, but sometimes we whispered procedural things in their ear. Asked about it once — “What did you whisper in the chairman’s ear?” — the answer was I was pointing out there was a motion already open, and he couldn’t ask for another motion w/o settling the first one.

The three years I worked as a budget staffer for the state legislature was highly educational about how law gets made.

@Michael Cain:

Now and then, we’re forced to remind acquisitions committees what the acquisitions law is.