The Psychology of Epstein’s Circle

Enough is never enough.

Despite the seemingly endless press coverage, I have paid only peripheral attention to the saga of the Epstein Files. While their namesake was clearly a monster, most of the commentary around his circle of celebrity acquaintances has struck me as wildly speculative and filtered through existing biases.

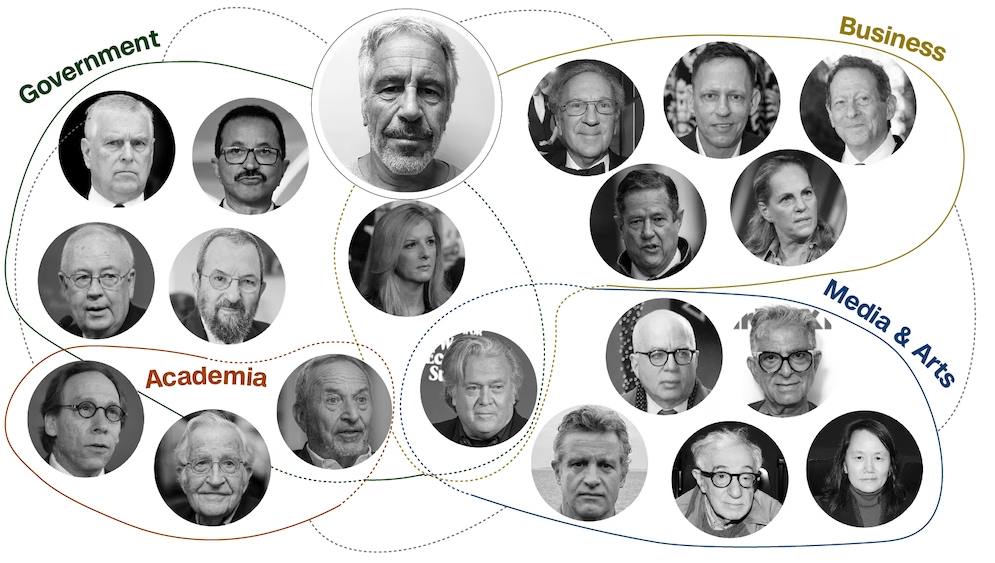

Still, I found the recent discussion between Ezra Klein and Anand Giridharadas on “The Infrastructure of Jeffrey Epstein’s Power” illuminating and worthwhile. The conversation is just shy of 90 minutes long and somewhat circuitous. I may post more on it separately but here, I want to focus on the vast web of powerful and important people who ingratiated themselves with Epstein, mostly to be part of his network, and thereby enabled him.

As Klein puts it early,

The most striking thing about the files is the range of Jeffrey Epstein’s elite network. You have someone here who is intimate at different times with not only Steve Bannon and Donald Trump but an Emirati businessman, Elon Musk, Noam Chomsky and Peter Thiel.

At the same time, it crosses ideologies. It crosses industries. It crosses professions. It is an extraordinary range of contacts — Republicans and Democrats, globalists and antiglobalists.

How is this one guy at the center of so many different kinds of people?

After a bit, he refers to an essay Giridharadas wrote for the NYT in November titled “How the Elite Behave When No One Is Watching: Inside the Epstein Emails.”

You wrote, in some ways actually movingly, about Epstein having a talent for friendship. He has a talent for being of use to people. He becomes an adviser to them. You can’t be a great con man without understanding human beings at a very deep level.

But there’s also just an endless transactionalism. An endless trading of information, money, connections, favor, powers — ultimately, women and girls. And what feels oftentimes like it is attracting them to each other is not always what I would think of as solidarity or a fellowship but: What can you do for me?

If you can be the one who finds it for them, that’s real power.

Giridharadas responds,

And it’s different needs, right? The money people may not need money, although they always want more of it. They often want to seem and feel smart. If you have met people in those kinds of worlds — finance people — even if you make a lot of money in it, they’re often very boring people.

I don’t say this as slander. They know it. I’ve had so many conversations with people in this world where there’s an insecurity about how boring they are. So they want something else.

Then there’s a bunch of academics. Academics, I think, really figure in this story in a way that feels surprising. It’s a tough era to be an independent thinker, so the academics want money and access.

Larry Summers, a former Treasury secretary asked Epstein, “How is life among the lucrative and louche?” He wanted access to a party scene that’s not available to him.

Everybody had something they needed. But his gift, if it can be called that, was understanding and mapping that so well.

Much later in the conversation, Klein observes:

But for some [his 2008 guilty plea to soliciting sex with a minor] was actually part of his mystique — that he was the one leading the life that they thought they had been promised.

Summers puts it in there: “lucrative and louche.” There are a lot of rich people — you’ve run into them, I’ve run into them — who made it to “lucrative,” and they thought at some point that would create “louche.” They were the grinds in school. They’re smart, they’re hard-working. They’re resentful. Maybe they had a tough time in high school. And they made it.

And all there was at the top was — I mean, there was money, which is great — but there are more meetings and more work and more work and more work. And that thing they were promised never showed up.

And here comes Epstein — and part of his whole mystique is that for him, it did. He has an island where there are parties, and those parties are legendary. Maybe you don’t really even know what goes on at them, but you’ve heard intimations — they’re pretty wild.

And that becomes not what is pushing people away from him, at least prior to the Miami Herald reporting. In these emails, what I see is it’s pulling people toward him. Because even that conviction is part of his loucheness. I mean, he describes it to people as he didn’t know she was underage.

But he’s living the life they do not feel themselves unleashed enough or capable of living.

To which Giridharadas responds,

Yes. For folks who haven’t spent time adjacent to any of these worlds, you might think that these people live in a kind of “Great Gatsby” fantasy. They don’t. Epstein was highly unusual.

This elite, as I described in The Times piece, is a kind of merito-aristocracy where they have aristocratic powers. But for most people, it’s not inheriting land or a family title that gets you into that world today. These are highly educated, credentialed people, for the most part.

[…]

So this is a group of people who, as it is in Washington, so it is across a lot of this American elite, that they work really hard and their life consists of not making mistakes. It’s conservative, it’s safe, it’s the straight and narrow. And they often lead quite boring lives.

[…]

So when Epstein came along — again, we talked about exploiting vulnerabilities — he offered these people, as you said so well, a life that maybe at some earlier point they thought would be the endpoint of making a lot of money in finance, but, in fact, they’re just sitting in some house in Connecticut, alone and scrolling X and maybe offering a toxic opinion on something. And this was this entree into something maybe different, maybe something they felt they were owed.

Klein follows this with a long soliloquy on powerful people, who seemingly have the resources and standing to stand up to President Trump—and in fact, did so in the first term–but have instead kowtowed this go-around.

Giridharadas agrees and explains it thusly:

I think we live in an age of — and there have been a lot of books about this — network power. That the way in which power works now has more to do with networks and the dynamics of networks.

And that has many implications. That means your connections are more of a source of power. If you go back a couple hundred years, the land you owned was a really big source of power.

I wonder if part of what is happening is, in an age of network power, courage becomes harder. Because if you think back to that person whose power came from being rooted in the community — they had some land, they were somebody in the town, maybe they were the deacon in the church on the weekend. They had multiple kinds of clout. They had some money they gave to the local civic thing. They maybe had a bunch of different things that might make them courageous about some other thing, so that if someone started to take over their political party who was a fascist, they would have support from their church community or from the sports league they were associated with — these other things.

A lot of those things have vanished. And your power really consists of your position and your number of connections and the density and quality and lucrativeness of those connections in the network.

[…]

I just wonder if courage is a value that has suffered in a network age, because to be courageous is to break ties. And the more valuable ties become — the more exponentially valuable more ties become — the more exponentially expensive it is to cut off that tie, to burn that bridge.

And it seems to me we are surrounded by elites who are much more afraid than their parents and grandparents were to take a stand to say: This crosses a line. Because maybe they fear, at some deep level, if you are out of the network, you go to zero very quickly.

It’s all very interesting, though I don’t think I’ve fully processed it.

The takeaway that most rang true to me is the degree to which even people most of us would find extraordinarily successful feel unfulfilled. Those who have made billions in business are often not famous and socially awkward. Movie stars may have money, fame, and invites to all the right parties, but they’re not necessarily respected for their brains.

A common theme is the degree to which the success just didn’t come with everything they dreamed it would bring. And here’s Epstein, a guy nobody ever heard of before the sex scandals, who got rich essentially as a con artist, who owns the most expensive house in Manhattan, has his own private islands, and parties as often as he wants to with whomever he wants to.

There’s no evidence that many, let alone most, of these people were pedophiles. But Epstein didn’t exactly go out of his way to disguise his predilections. Most of these people, at the very least, should have had strong suspicions. And, as both Klein and Giridharadas note several times, a whole lot of other luminaries saw Epstein for what he was and refused to have any part in it.

Is there a nonpictured prominent person missing from the panel of bad guys, fools, and criminals that provided oxygen to the Epstein family?