There Was No Great Resignation

The media has been awash for months in stories about millions of Americans quitting their jobs in the wake of the COVID pandemic, with countless analyses arguing that workers have taken stock of their priorities and decided that the old rat race just wasn’t worth it. Alas, the distinguished economist Bart Hobijn reports, nothing unusual happened.

The record percentage of workers who are quitting their jobs, known as the “Great Resignation,” is not a shift in worker attitudes in the wake of the pandemic. Evidence on which workers are quitting suggests that it reflects the strong rebound of the demand for younger and less-educated workers. Historical data on quits in manufacturing suggest that the current wave is not unusual. Waves of job quits have occurred during all fast recoveries in the postwar period.

The labor market recovery since the depth of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020 has been the fastest in postwar history. This historic rebound is evidenced by the steepest decline of the unemployment rate and the fastest growth in payroll employment on record (Hall and Kudlyak 2021).

At the same time, the share of workers quitting their jobs—either to take new jobs or to exit the labor force—has also hit its highest level since 2000, when the data began being collected. This recent spike in quits has been referred to as the “Great Resignation.” Some have interpreted it as a wave of resignations, driven by people reconsidering their career prospects and work-life balance, that is drastically altering the labor supply. In this Economic Letter, I provide two pieces of evidence that cast doubt on this narrative and, instead, suggest that the high rate of quits is simply a reflection of the rapid pace of overall labor market recovery.

First, I find that the increase in the quits rate is driven by young and less-educated workers in industries and occupations that were most adversely affected by the pandemic. This is also where payroll employment growth has been high recently, offsetting the job losses incurred in 2020.

Secondly, the Great Resignation is not so great after all. Historical data on the quits rate in manufacturing point to waves of quitting being common during fast recoveries when employment growth was high. Thus, it is not an anomaly, but instead fits the pattern of many past rapid recoveries.

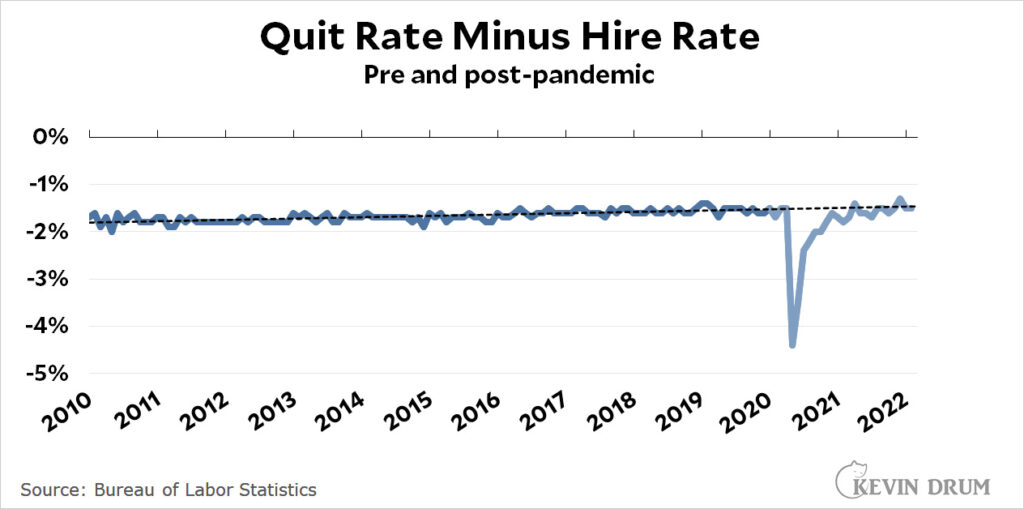

There’s a whole lot more but that’s the upshot. Kevin Drum, who pointed me to the piece, observes, “I continue to wonder where this narrative ever came from in the first place.” He produces this graph:

and observes,

The quit rate dropped precipitously at the start of the pandemic for obvious reasons: workers were being laid off by the millions and no one in their right mind wanted to enter a job market like that.

But that turned around shortly and the quit rate went back up. Critically, though, the quit rate merely rebounded to its old Great Recovery trendline. It may be that 3% is a “record” quit rate, but it’s only very slightly above trend.

He amplifies this with a second chart:

and observes,

This chart shows the difference between the hire rate and the quit rate. As you can see, it’s very, very stable. The quit rate during the Great Recovery has been consistently about two percentage points below the hire rate.

Bottom line: There was never really anything to the Great Resignation theory. Quits and hires spiked and rebounded during the pandemic year of 2020 but were back to normal by the start of 2021. I’m not sure why you need anything more than this to understand what was going on.

Among the many problems with daily journalism and punditry is that they essentially force half-baked analysis based on incomplete information. It was perfectly reasonable to treat the massive economic upheaval caused by the pandemic as unique rather than an ordinary recession. And the fact that people seemed to go back to work slowly—or not to be looking for work at all—once governments gave the green light to reopening reinforced that belief.

This is compounded by the biases of the type of people who predominate in journalism and punditry, who tend to be highly educated and to view wage labor as something one would do only under coercion. (I remember, for example, some Ezra Klein podcasts arguing that it was unjust to force people to choose between mundane jobs that weren’t self-actualizing and the inability to afford the basic necessities of life.) That a suddenly-empowered proletariat was throwing off its chains while sounding a barbaric yawp was an impossible-to-resist feel-good story. And the reliance of anecdote over data—another characteristic of most daily journalism—made it really easy to tell this story over and over using specific examples.

Interesting to balance this against the many, many (generally conservative) talking points about ‘People don’t want to work any more!’ and ‘People are just sitting at home enjoying their benefits!’.

I suspected this might be the case, but it’s disappointing. I much preferred the casting off chains narrative.

Absolutely true. It’s funny because I’m happy being a NYT bestselling author – that’s a lifelong title one is entitled to tattoo on one’s forehead – but I was also happy waiting tables. I’m proud of my ability to churn out a 400 page book in six months, but I have to tell you, I’m equally proud that I can put out a Caesar salad for two, using 13 scratch ingredients, at table-side, in two minutes flat, while keeping up the banter.

Squeeze half a wrapped lemon in the salad bowl. Add anchovy and crush with two forks. Add garlic clove and crush. Half teaspoon of Dijon, an ounce of vinegar, swirl Worcestershire sauce, one egg yolk, and here’s the showbiz: do a high slow pour of two ounces of oil while whipping with twin forks to create an emulsion. Add the Romaine, toss with salt, pepper, croutons and parmesan. Serve on chilled plates.

I’ve squatted in public restrooms to scrape shit stains, and I’ve stood on stage before a thousand kids who thought I was Jesus. Same guy. There are no unimportant jobs. If someone is paying you it’s because they need you. Your sense of yourself should transcend your job, there’s your job, and then there’s you, not the same thing. Easy to say, hard to do.

From memory, so possibly suspect, but I recall a fairly lengthy stretch when the recovery was just starting where the initial jobs reports each month were (a) really depressing and (b) quite wrong. Writers were trying to explain why people weren’t going back to work, when the actual story was why are the first month statistics so consistently wrong? Of course, no one knew that the statistics were so bad until six months to a year after the fact.

I have long said that anyone who writes a story/column based on the initial job reports should be prosecuted for journalistic misconduct of some sort.

There’s gotta be a narrative, no matter how hard they have to strain for it.

Re

It is a problem of Anectdote as analysis and journalists in their narrativization recasting “a bunch of people I know or was introduced to” as some representative sample. Combined with the general innumeracy of almost all journos.

Essentially the misapplication of one tool inappropriately to another subject.

The recasting of anectdotes of a bunch of people I talked to before deadline into grand trends and observations is rather dangerously wrong when one is writing about things that are not inherently driven by a small group of actors. It works perfectly fine for I suppose stories focused on a small pool of actors (as perhaps a political or business or labour organisation elite or other decison-making group), but for any kind of comment on a mass development of any kind, it is a failure and active self-deception for both journo and reader. (See e.g. Afghanistan narratives).

Large society trends require real statistics for any kind of chance to be properly informative.

I first became painfully aware of this back in my Mashreq days in the midst of the US Iraq war on coverage deriving from my little geographic spot, as I noticed that in certain high profile Anglo media I knew exactly who they were talking to and recognised the narrowness of the sourcing (as their sourcing tended to concentrate in a certain social circle of oppositionally minded English speaking Arabs who happened frequently to be my alt-socieity pub drinking companions I liked to escape from my PE world. Even more weird was a few occasions when I realised I was the source of the journos arty, but my rather narrow expat PE fund perspective was being recast in some broad fashion – of course I would agree with my own opinions but it was very weird to see recast into a broader narrative.)

Still recognise this now when there is reporting on my current geographical focus….

@Michael Reynolds: I know a woman (back home) who works as a flagger for a county road crew. She loves it. She’s outside, and doing something valuable and meaningful (repairing roads, which she drives on, along with everything else).

The idea that manual labor isn’t self actualizing is deeply flawed, for sure.

Two notes on this:

* I’ve definitely seen many unusual things, in the DC area, in the technology industry, and the statistics for us and our peers are more anomalous than what the totals show.

* We aren’t the whole industry.

The article above seems to say “there was no Great Resignation! Because national statistics don’t show it,” but I’d want to see focused cross-tabs – because my suspicion is that the people who’re talking about the situation are, like me, looking around at a subset of the total, and the people who’re talking about the statistics are looking at things that are summarized.

In the technology industry, at least, you can have some interesting second and third order effects when you have uncertainty in a few core businesses and locations, because it affects the availability of resources elsewhere.

@Michael Reynolds:

Doesn’t that take three hands? If so, your avatar picture doesn’t do you justice…

@Lounsbury:

There is the stereotypical NY Times “About Town” lede, “Why is the Monocle Making a Comback?”, based entirely on a deadline challenge reporter having recently seen an eccentric wearing one and then asking three friends about and one of the friends kinda sorta thought they might’ve seen one once. Somewhere.

I don’t know — people have been leaving where I work in droves. If it isn’t a great resignation, then it must just be that it is a terrible job.

Here’s how a meeting went not to long ago:

PM: And it’s with a heavy heart that I announce the departure of one of our own.

A: I didn’t know it was public yet, but it’s been great…

PM: I was referring to B

C: I’ll miss all of you, I’m moving on to such and such at the end of the month

PM: No, not C, B

B: uh, yeah, I’m out of here on the 20th.

At this point, my boss jokingly asks if anyone else is leaving, and I regret not taking the opportunity. But I didn’t want to quit suddenly in the middle of a meeting at another job.

@MarkedMan:

Nah. Hold two forks in your right hand and beat while you do the high pour with your left. Gotta have some showbiz in tableside. More fun doing flambées, which can be made dramatic if, after you’ve caught the brandy alight, you hold a teaspoon of superfine sugar high above and sprinkle it down in a sugar cloud. You can cause quite a nice little explosion. Cherries jubilee, crepes suzettes, bananas foster, they’re all more fun with singed eyebrows and panicky looks from your manager.

The best though was tableside spinach salad. All the same stuff as the Caesar but while you’re doing that you’re also cooking lardons of bacon on a burner. Add the bacon when crisp, a bit of sugar, and you’re all set. And there’s nothing like the smell of frying bacon to catch the interest of the other diners.

@Gustopher:

Both my wife and I have walked out of restaurants mid-shift. I handed my tickets to another waiter, the manager said, you can’t, and yet I did. Bye bye and then there was cool, clean outdoor air on my face. Almost as good as sex. My wife walked out with a loud, ‘take this job and shove it up your ass.’ She wishes she could edit that into something more original.

@Gustopher:

We’ve had a lot of people leave. However… there’s good reasoning behind a lot of it. In mid-2020, height of COVID, our company looked at ways to conserve funds while not laying anybody off. They offered early retirement to those who were close, and a “buy-out” of up to $50k (based on longevity with the company) for anyone else.

In one fell swoop, we lost about 10% of our employees A significant number were planning on retiring soon anyway, so this just hastened it. The other large portion were young people who saw several grand as a nice bonus, knowing that they’re hot-shot programmers and engineers and could find work elsewhere fairly easily.

And, of course, there were a small few whose “call back from furlough” was… umm… “delayed for a while”. 🙂

I’m betting a fair number of companies did the same thing, giving an artificial boost to the immediate “quit” numbers–which returned to previous levels when normal business resumed.

Our issue now, is hiring on new people. Assembly is down about 20% from pre-COVID numbers, Tech Support is down 3 positions out of 12 (two moved up into new roles, and 1 actually moved down within the company because he couldn’t handle the stress). Custodial is down (one person quit, another moved up within the company). Marketing lost one to retirement, and another to job shifting.

Those positions will be filled eventually, but we’re still playing cautious with the finances until we’re fully back on our feet.

@MarkedMan:

You’ve figured out his secret. Michael Reynolds is actually a Motie.

And here, Michael Reynolds, is what separates you from “foodies” who insist on dropping whole anchovies on top of the salad for show. Served thus, they are merely salty oily little annoyances; crushed into the dressing, they are lovely enhancements to the other ingredients.

@Gustopher:

Same. Huge turnover in the last year compared to a relatively stable decade.

I’ve had 4 people on my direct report team leave in the last year – one was anticipated due to near retirement and one we knew was a flight risk due to be unhappy that her career wasn’t skyrocketing as expected but the other 2 were out of left field. In teams we work with closely, one was completely wiped out as 3 out of 3 left within a month of each other and another had over 4 go unexpectedly as well. Some made sense – a spouse moved and they didn’t want to do remote, others were head-hunted and we couldn’t counter-offer enough to keep them. Some have hated the chaos, disruption and extra work left behind when all their coworkers leave and want to go….. and I’ve always wondered what they thought when they arrive at a new place in chaos because you’re replacing someone else who peaced out for that same reason.

We’re a decent place to work – pay’s pretty good with decent benefits (unlimited PTO you can actually use without complaint!). However, there’s a “I can do better fever” sweeping through the place with folks seeking 6 figure pay or higher status titles, especially among the younger Millennials and Gen Zers. You know that college student that thought they were gonna score $100K+ right out the gate? Now they can and they’re jumping on it. It’s almost contagious – I’ve watch a resignation happen among a peer group or circle of friends and suddenly everyone’s doing it to the point we can accurately guess who’s next.

People are definitely moving around. Perhaps it’s just hitting businesses and trades that didn’t see such high turnover before but to say it’s fairly normal? Pfft – tell that to my company that’s seen more resignations in the last year then the last decade combined.

@Michael Reynolds: @Joe: I remember Mom making Caesar Salad in the 60s, especially when guests came over. I also remember it had to be a wooden salad bowl. It was a production.

Also, just realized that the anchovies were the umami flavor before umami became a thing in the West.

@Michael Reynolds: Mine was less immediately dramatic.

In a planning meeting, I was asked what I thought, and so I said what I thought — “I think I should just give notice.”

This caught people by surprise. They were expecting “I think this will take longer than you’re expecting” or “Does this really add value?” or really anything other “I think I should just give notice.”

I was talked into staying on a bit longer to help transition, then dragged that out until a stock vesting cliff (enough money to pay off my house), and then got myself on a performance plan so I could give the severance check to local food banks.

(A benefit of a large corporation is that they have a very rigid process for letting people go, and that deviating is very hard and requires someone to be a threat — you should always ask about the severance package when interviewing somewhere)

The great fun was the coaching plan in the last few months, which was a mixture of “why are you still here?” (“you asked me to stay longer.”) and “why haven’t you done X?” (“Because you’ve given me bad incentives, and now if I fail your coaching plan I get a severance check which I will give to a food bank, combining spite and altruism.”)

My boss thought I was somehow joking about my plan to get fired for charity, kept setting up very clear, measurable goals, and I would make sure to fail them while entertaining myself by doing other things that really did need to get done (solved a variety of long standing problems, actually), which just gave him hope that he could steer me into a productive employee.

He was very confused and increasingly angry with me. Eventually his boss wandered by and asked me why I was still there, so I explained it to him. He asked if I had told this to my boss, and I explained that I think my boss thought I was joking. Grandboss sped the process along.

Grandboss did ask “what the hell is wrong with you?” and I explained that if you give someone bad incentives, they will behave badly.

My boss seemed to forgive me after I sent him the donation receipts from the food banks.

All in all, my spontaneous quit took five months to complete, which I thought would be a record epic slow-quit.

Less than a year later, though, a friend beat my record by giving notice, and then getting in a car crash, being in a coma for a while, months of rehab and the company keeping him on so he would have health insurance and disability insurance. He even started working there again part time, and then full time, and then they fired him. They even gave him severance.

I still think “getting fired for charity” was better than “getting crushed in a car crash and spending months in a coma,” at least so far as I don’t walk with a limp.

@MarkedMan: Yes precisely for all that one can easily understand the practical constraints that generate this (both at Journo level and publication level). But it does render such reporting generally useless, mere noise.

@Gustopher and @KM: And so illustrates the exact audience for such usless journalism, the own-experience confirmation. Of course as the journos and the main readership will tend to align to certain broad sociological profiles (urban, uni educated, not labour but office / non-manual labour focus), becomes a house of mirrors.

Of course it may very well be very true that certain specific sub-sectors and professions are indeed seeing elevated turn-over (certainly my malingering US side has in comparison to historical, but then that would fit precisely the journo-scope biais, their profile). However that does not of necessity translate into majority of employement profile. The general statistics rather indicate that in fact the anectdotal analysis applies to a very journo and journo majority readership visible set of segments.

@Joe:

Exactly, the anchovies are part of the dressing, they aren’t just slimy croutons.

@Scott:

Umami, sadly a concept that did not exist at the time when I tried to explain to customers that yes, they did want the anchovies. But why, I don’t like anchovies, wah. STFU and eat the salad I give you – is what I did not say.

@Gustopher:

Good lord, that must have been a fun time, still at the job after telling them to shove it.

But a nice move donating to a food bank. I might have gone with ‘a portion of the proceeds.’ What portion? Um. . .

@Michael Reynolds:

I’ve never walked out mid-shift, but I have quit from three restaurants with no notice. One I sorta gave notice. I let them know that I had interviewed for a touring job–I didn’t know that the new job would give me 1 day to get my ass to Hershey, PA.

The one before that was working at the Olive Garden, washing dishes. I went through the entire hiring process–including the idiotic corporate “training” videos–showed up for my first day, and at lunch break got told I would have to shave my beard in order to work there. I quit, but finished the shift (no other dishwashers on duty, and I wasn’t going to do that to the wait staff).

The first time, I was 15. Amazing little Victorian restaurant. The owner sold to a crew from Chicago who seriously fucked the place up–on the first night! There was a meeting after we closed and the owners said “Anyone who doesn’t like our way of doing things can quit.” I quit. Within 2 weeks so had the entire rest of the staff–including the 3 sons of the previous owner.

@Gustopher:

That must have been a while ago. Now, most big places call in a security guard and give you a box the moment you hand in your notice. IT gets a call and all your access to everything is turned off at that moment. You still get paid for your 2 weeks, but you’re not allowed anywhere near the building.

@Michael Reynolds: I’ve found that the best time at any job is once you have given notice — you just do what you want, and there are no consequences or stresses. You take each day as it comes, and when you’re done for the day, you’re done. You tell people why you think their ideas won’t work, how they can test it beforehand, and if they do or don’t… whatever, dude.

It leads me to a variation of the famous scene from Glengarry Glen Ross:

ABQ: Always Be Quitting

Also, it was easy to give the whole severance to the food banks — it was way, way less than the stock vesting. Plus, I got paid the entire time I was working towards getting fired.

—-

I’ve given notice at my current job because “I don’t think this is a particularly good use of my time… on Earth.” Nothing particularly dramatic though. Just in the coasting out the door phase. So far, it’s the best part of the job.

(There was a conversation a few months ago, where my boss said “If you want to have a greater impact, there are a bunch of vacancies above you, and we could start giving you some of those tasks to see if you like it and do well…” to which I responded “The vacancies above me are because those jobs suck — all responsibility with no actual ability to change anything. Why would I want that? Previous people clearly didn’t…” so I’ve clearly been in quitting phase for a while)

@Lounsbury: There are a number of segments of the economy showing increasingly high turnover, and they are pretty broadly distributed.

Tech and “unskilled” trades are likely having the biggest turnover, as the unemployment rate is low and the skills are either in very high demand or easily transferable. It means that workers don’t have to put up with as much shit, or at least they can go find different shit to put up with elsewhere.

Once you have journalists noting that there is a lot of resignations in a few unconnected sectors, and if they’re looking at the early jobs numbers which magnified it, it’s pretty easy to build a narrative. It’s not that the journalists were in their bubble, but that when they looked outside their bubble there were enough stories to appear to confirm it.

And, given that graph that shows a slow and steady increase in job turnover, each month is a new record even with good data. The narrative causes the media to see what has been slowly happening for a while.

There’s a general realignment in areas where workers can exercise more power — unionization campaigns are succeeding at the low end (Amazon warehouse, Starbucks), and workers are demanding (and getting) more at the higher end.

If you’re interested in more stories along these lines, check out Reddit’s Antiwork site.

https://www.reddit.com/r/antiwork/

Many tales of bad bosses and the how workers respond.

@Joe: Clearly, you’ve never had dried anchovies drizzled with gochujang and sesame oil served as a side dich at any Korean restaurants you’ve gone to. You put a pinch of it on top of the rice and bulgogi (or bulgalbi or samgyapsang) that you roll in a lettuce leaf (or sesame leaf if you’re me). I get mashing up the anchovy in the dressing of the salad, but I’d be okay with them sprinkled on top, too.

Then again, I make Caesar salad with bottled dressing at home and have never been willing to pay what the show costs at a make-it-at-your-table restaurant. I’m sure the show is as spectacular as the one at Benihana, though. (Which I have also never been to, btw, I’m going by what people have told me and the John Belushi SNL skit.)

@Scott: “Also, just realized that the anchovies were the umami flavor before…”

So the article that I read recently by the chef who admitted that the principle effect in “umami” taste is “salty” was correct? Good to know.

@Mu Yixiao: “Now, most big places call in a security guard and give you a box…”

That’s been the procedure I’ve known about everywhere I worked with office staff since the 1970s. The only place I’ve ever seen situations where a terminated/resignation employee finished out some fixed span of time have been education and healthcare. (Though, when I tendered my resignation at Food Services of America, I was asked to stay on one more week–so that they wouldn’t have to pay a permanent employee extra for working the skeleton Friday-night shift that week.)

@Arnold Stang: Thanks! Those posts were hilarious! (In the “if you can’t laugh at them you’d have to get a gun and start shooting people” sense, that is. 🙁 )

@KM: “…and I’ve always wondered what they thought when they arrive at a new place in chaos because you’re replacing someone else who peaced out for that same reason.”

That can be a problem, but you would be getting a sizeable raise. If a company has the attitude that they’ll pocket the departing worker’s salary and make the others do the work, then staying is clearly and openly a bad game.

I never accepted the ‘Great Resignation’ theory, because it was clearly ridiculous. Unemployment, even with COVID supplements, would only cover the living expenses of a few people.

IMHO, what was happening was:

1) The pandemic + immigration + difficulties in childcare knocked out a segment of the work force.

2) Many, many people had had no raises in years.

3) Once the movement started, that freed up more openings, and gave more people hope.

The last is important, because our system is built on 50% or so of the work force being powerless, and nothing frightens the elites and their wh*res (e.g., the MSM) like peasants being uppity.

@Barry: Look at the graph. In the past decade, the percentage of people quitting has doubled.

“The Great Resignation” is the media noticing this longer term trend, and assuming it all changed in a two month span.

Something has been happening.

@Gustopher: I have seen longer-term graphs, and quits are highly cyclic with the economy. Which has been improving for a while.