Too Many Laws?

A Supreme Court Justice says our laws and regulations are out of control.

Justice Neil Gorsuch and his former clerk Janie Nitze take to the Atlantic to argue “America Has Too Many Laws.” While I think they’re probably right, their argument is unconvincing.

Our country has always been a nation of laws, but something has changed dramatically in recent decades. Contrary to the narrative that Congress is racked by an inability to pass bills, the number of laws in our country has simply exploded. Less than 100 years ago, all of the federal government’s statutes fit into a single volume. By 2018, the U.S. Code encompassed 54 volumes and approximately 60,000 pages. Over the past decade, Congress has adopted an average of 344 new pieces of legislation each session. That amounts to 2 million to 3 million words of new federal law each year. Even the length of bills has grown—from an average of about two pages in the 1950s to 18 today.

The world is a radically more complicated place than it was a century ago and considerably more so than even forty or fifty years ago. It’s not surprising, then, that we need laws now that we didn’t then. Complicated matters require more detailed legislation (unless one wants to leave the details to experts in the bureaucracy, which I’m given to understand Gorsuch does not). Further, there has been a growing tendency, for a whole host of reasons, to pass omnibus bills rather than standalone measures.

And that’s just the average. Nowadays, it’s not unusual for new laws to span hundreds of pages. The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 ran more than 600 pages, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 almost 1,000 pages, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021—which included a COVID-19 relief package—more than 5,000 pages. About the last one, the chair of the House Rules Committee quipped that “if we provide[d] everyone a paper copy we would have to destroy an entire forest.” Buried in the bill were provisions for horse racing, approvals for two new Smithsonian museums, and a section on foreign policy regarding Tibet. By comparison, the landmark protections afforded by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 took just 28 pages to describe.

An omnibus budget bill is going to be much more detailed than a standalone measure. And I’m not sure the Civil Rights Act is a great example to emulate, given that we’re still litigating what it means six decades later.

These figures from Congress only begin to tell the story. Federal agencies have been busy too. They write new rules and regulations implementing or interpreting Congress’s laws. Many bear the force of law. Thanks in part to Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, agencies now publish their proposals and final rules in the Federal Register; their final regulations can also be found in the Code of Federal Regulations. When the Federal Register started in 1936, it was 16 pages long. In recent years, that publication has grown by an average of more than 70,000 pages annually.

Meanwhile, by 2021 the Code of Federal Regulations spanned about 200 volumes and more than 188,000 pages. How long would it take a person to read all those federal regulations? According to researchers at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, “over three years … And that is just the reading component. Not comprehension … not analysis.”

Even these numbers do not come close to capturing all of the federal government’s activity. Today, agencies don’t just promulgate rules and regulations. They also issue informal “guidance documents” that ostensibly clarify existing regulations but in practice often “carry the implicit threat of enforcement action if the regulated public does not comply.” In a recent 10-year span, federal agencies issued about 13,000 guidance documents. Some of these documents appear in the Federal Register; some don’t. Some are hard to find anywhere. Echoing Justice Brandeis’s efforts, a few years ago the Office of Management and Budget asked agencies to make their guidance available in searchable online databases. But some agencies resisted. Why? By some accounts, they simply had no idea where to find all of their own guidance. Ultimately, officials abandoned the idea.

Again, I’m sympathetic to the idea that we have too many laws and regulations. But mere page counts don’t tell me anything useful. My general preference would be to have fewer, simpler laws and regulations so that it’s easy for ordinary citizens to know what the rules are. But the fact of the matter is that things like the tax code and workplace safety laws and regulations are incredibly complicated—made more so by powerful people hiring armies of lawyers to skirt their plain intent and thus requiring a cat-and-mouse game where more laws and regulations are added to close loopholes.

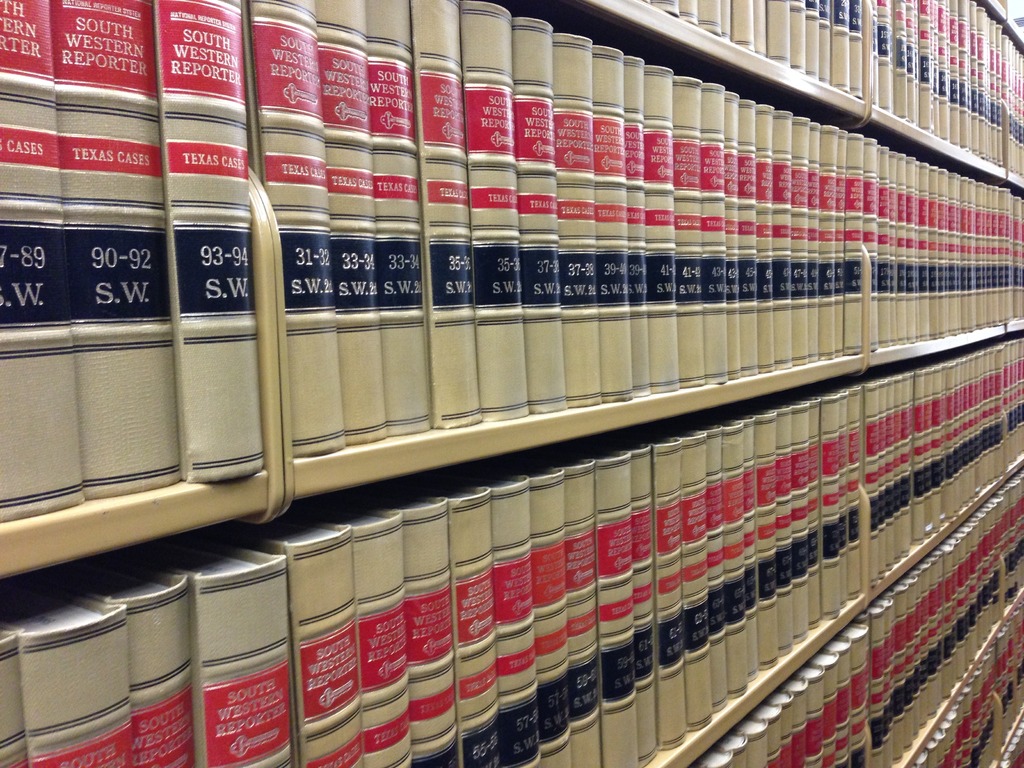

Judicial decisions contain vital information about how our laws and rules operate. Today, most of these decisions can be found in searchable electronic databases, but some come with high subscription fees. If you can’t afford those, you may have to consult a library. Good luck finding what you need there: Reported federal decisions now fill more than 5,000 volumes. Each volume clocks in at about 1,000 pages, for a total of more than 5 million pages. Back in 1997, Thomas Baker, a law professor, found that “the cumulative output of all the lower federal courts … amounts to a small, but respectable library that, when stacked end-to-end, runs for one-and-one-half football fields.” One can only wonder how many football fields we’re up to now.

So, I haven’t the foggiest idea how many of those cases shouldn’t have been heard or whether those opinions were verbose. But, again, it contributes to the problem that there’s simply no way for ordinary citizens to know what the law is.

As you might imagine, much in this growing mountain of law isn’t exactly intuitive. Did you know that it’s a federal crime to enter a post office while intoxicated? Or to sell a mattress without a warning label? And if you’re a budding pasta entrepreneur, take note: By federal decree, macaroni must have a diameter between 0.11 and 0.27 inches, while vermicelli must not be more than 0.06 inches in diameter. Both may contain egg whites—but those egg whites cannot constitute more than 2 percent of the weight of the finished product.

Everyone knows about mattress warning labels, actually. And, given that post offices are federal installations, it stands to reason that there are federal laws governing conduct there. As to the size of pasta noodles, one could certainly argue that consumers can simply look at them and decide for themselves whether they’re too big or small. On the other hand, there’s rather substantial value in standardization so that one knows what one is buying when there are shelves and shelves of competing products.

Further, this gets to a point that applies to many of the complaints here: the overwhelming number of laws and regulations apply to a very narrow sector. I don’t know how long the portions of US Code or the Federal Register pertaining to pasta are but am reasonably confident that I’m not going to run afoul of them since I’m not in the business of manufacturing or distributing pasta products.

If officials in the federal government have been busy, it’s not as if their counterparts at the state and local levels have been idle. Virginia prohibits hunting a bear with the assistance of dogs on Sundays. In Massachusetts, be careful not to sing or render “The Star-Spangled Banner” as “a part of a medley of any kind”—that can invite a fine.

So, this is simply silliness unworthy of someone of Gorsuch’s stature. There are surely lots of antiquated laws on the books at the state and municipal level that seem quite silly. Presumably, they had a rationale at one point. But, unless they’re actually being enforced, it’s not obvious what the harm is.

On the other hand:

The New York City Administrative Code spans more than 30 titles and the Rules of the City of New York more than 50. In 2010, The New York Times reported on the regulatory hurdles associated with opening a new restaurant in the city. It found that an individual “may have to contend with as many as 11 city agencies, often with conflicting requirements; secure 30 permits, registrations, licenses and certificates; and pass 23 inspections.” And that’s not even counting what it takes to secure a liquor license.

Much of this, presumably, was considered necessary because people who opened restaurants were doing things that were harmful to their customers or employees. But, almost certainly, it could be streamlined to make things less onerous.

To appreciate the growth of our law at all levels, count the lawyers. In recent years, the legal profession has proved a booming business. From 1900 to 2021, the number of lawyers in the United States grew by 1,060 percent, while the population grew by about a third that rate. Since 1950, the number of law schools approved by the American Bar Association has nearly doubled.

This is an odd sleight of hand. The first statistic simply reflects what we’ve already discussed: the world is a lot more complicated now than it was before the invention of the airplane and the computer. The second actually contradicts the first: the population has more than doubled since 1950, so we’re arguably actually under-growing law schools.

Our legal institutions have become so complicated and so numerous that even federal agencies cannot agree on how many federal agencies exist. A few years ago, an opinion writer in Forbes pointed out that the Administrative Conference of the United States lists 115 agencies in the appendix of its Sourcebook of United States Executive Agencies. But the Sourcebook also cautions that there is “no authoritative list of government agencies.” Moreover, the United States Government Manual and USA.gov maintain different and competing lists. And both of these lists differ in turn from the list kept by the Federal Register. That last publication appears to peg the number of federal agencies at 436.

One suspects this is as much a matter of coding as counting. There are dozens of agencies within the Defense Department alone.

Reflecting on these developments sometimes reminds us of Parkinson’s Law. In 1955, a noted historian, C. Northcote Parkinson, posited that the number of employees in a bureaucracy rises by about 5 percent a year “irrespective of any variation in the amount of work (if any) to be done.” He based his amusing theory on the example of the British Royal Navy, where the number of administrative officers on land grew by 78 percent from 1914 to 1928, during which time the number of navy ships fell by 67 percent and the number of navy officers and seamen dropped by 31 percent. It seemed to Parkinson that in the decades after World War I, Britain had created a “magnificent Navy on land.” (He also quipped that the number of officials would have “multiplied at the same rate had there been no actual seamen at all.”)

I haven’t the foggiest idea why the Royal Navy grew so much during that period (although it included what we no know as World War I) but I’m not sure that it has much bearing on whether the United States has “too many laws.”

Does Parkinson’s Law reflect our own nation’s experience? In the 1930s, the Empire State Building—the tallest in the world at the time—took a little more than 13 months to build. A decade later, the Pentagon took 16 months. In the span of eight years during the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration built some 4,000 schools, 130 hospitals, 29,000 bridges, and 150 airfields; laid 9,000 miles of storm drains and sewer lines; paved or repaired 280,000 miles of roads; and planted 24 million trees.

Compare those feats to more recent ones. In 2022, an op-ed in The Washington Post observed that it had taken Georgia almost $1 billion and 21 years—14 of which were spent overcoming “regulatory hurdles”—to deepen a channel in the Savannah River for container ships. No great engineering challenge was involved; the five-foot deepening project “essentially … required moving muck.” Raising the roadway on a New Jersey bridge took five years, 20,000 pages of paperwork, and 47 permits from 19 agencies—even though the project used existing foundations. The Post reported that in recent years, Congress has required more than 4,000 annual reports from 466 federal agencies and nonprofits. According to the lawyer and author Philip K. Howard, one report on the printing operations of the Social Security Administration took 95 employees more than four months to complete. Among other things, it dutifully informed Congress of the age and serial number of a forklift.

The extent to which comparing emergency situations like the Great Depression and WWII to ordinary ones is useful is less than obvious. But it’s doubtless true that the proliferation of regulations has made it much more difficult and expensive to build.

There’s a whole lot more to the article but it’s mostly anecdotal. But, overall, the piece doesn’t do a good job of selling an argument to which I’m naturally sympathetic.

Unfortunately, Justice Gorsuch comes across as a very silly man. Basically, the reason we have regulations is so that we have definitions and don’t have to go to court every time there’s a question. And considering that we’re a Common Law country, we’d end up in the same place, only with having taken N more years to get there, with a lot of damage done during the way. Does Justice Gorsuch realize it took 10 years before a private cause of action was made possible under Hatch-Waxman?

This is pretty rich coming from a guy who overturned Roe.

Especially since his (and his buddies’) argument was pretty much “there is no right to abortion, so feel free to make up all the new laws that you want.”

The hypocrite.

Yeah, I’d love to eat at a restaurant in where they just hook up everything on their own with no inspection. Gas, freezers, ovens, electricity–you name it. What can go wrong? Just find the cheapest contractor and run with it, I say.

Why do Republicans say all the time that they support small business? Because it sounds better than admitting they support giant multi-national corporations.

Why does Gorsuch say he’s concerned about the effect of regulation on small businesses and consumers? Because it sounds better than admitting he’s paid to worry about the effect of regulation on giant multi-national corporations and Chuckles Koch.

I think we could make room for a few new laws, for example laws outlawing the open corruption of the court on which Mr. Gorsuch sits.

“The world is a radically more complicated place than it was a century ago and considerably more so than even forty or fifty years ago.”

I immediately knew this is where this argument would go. Talk about unconvincing: technologically more complicated does not infer some sort of linear (or exponential) correlation with legally more complicated.

But then:

“Further, there has been a growing tendency, for a whole host of reasons, to pass omnibus bills rather than standalone measures.”

And:

“..made more so by powerful people hiring armies of lawyers to skirt their plain intent and thus requiring a cat-and-mouse game where more laws and regulations are added to close loopholes.”

Which I think pretty much hit the nail on the head. Regulatory capture schemes and the natural organizational tendency for bureaucracies to expand their scope, power – and budgets – is not exactly earth shattering news. Those are no doubt the prime culprits. And I find the antiquated law argument to be trivial, and fixable: sunset provisions.

We have way too many laws. We have way too many unproductive people trying to throttle productive people. We have way too many people trying to game the system of laws.

Anyone in business knows that, depending on venue, trying to get any project through regulatory processes is a nightmare, and largely anti-growth. Mostly a tool for one side or the other. Given that our real unemployment rate is probably in the 8% range we ought to be thinking long and hard about that.

@drj:

No, the argument was it was not provided for in the Constitution, and was remanded to the States.

Am I supposed to take someone seriously who chooses not to understand why inventories of government assets are important?

I am inclined to think we probably have too many laws. Special interest groups dominate, especially wealthy ones. Rich people and corporations have enough influence that they can have laws written to benefit them. Someone should probably point out to Gorsuch that his tribe passed Citizens United to make this worse.

That said, the griping about the number of pages in a law really bugs me. First, if the laws were actually adequately written with enough detail we wouldn’t see so many suits going to federal courts so that they can interpret “what they mean”, which often means that the judges just decide stuff according to their own political beliefs. Second, as you point out James, stuff is more complicated, the nation is larger and we do have more lawyers. Take health care, my sector. Laws passed regarding health care 100 years ago didnt need to be long since health care didnt really have that much to offer. Now the science, technology, pharmacology is huge and complex.

If anything, Gorsuch should be complaining about poorly written laws. He should acknowledge that under his court he claims that courts have the expertise to rule on highly complex science and technology issues, not needing the help of agencies with true expertise. He should acknowledge that courts now accept as experts people with no true expertise, just a political POV that meshes with what judges want to believe. Why not more attention to SLAPP suits?

Steve

@Jack:

Yeah, what I said.

Except, of course, that there is a due process clause in the 14th Amendment, which for many, many years has been understood to include such a thing as substantive due process in addition to procedural due process. (There is, of course, also such a thing as the 9th Amendment.)

Substantive due process means that the government needs to have a compelling interest in order to prohibit something, i.e., no prohibition against blue clothes because a legislature decided it didn’t like that color.

Dobbs, of course, doesn’t specify any compelling state interest in regulating abortion access. It all boils down to “We don’t like it, so let’s allow state legislatures to outlaw it.”

But since you adore a wannabe dictator, you obviously don’t care about personal liberty and could care less if the state restricts personal freedoms. We see what you are.

There are a lot of good points that Jack brings up.Cleaning up laws (by updating, eliminating, retracting, etc.) is not fun and is just grunt work. Therefore, it is not done. I agree with Jack. Sunset provisions would go a long way to help there. But it is not done. Why?

@Jack: There are a lot of good points that Jack brings up.

However, it all depends on one’s perspective and place in the national ecosystems. What I think which rules and regulations are important is much different than what Gorsuch thinks are important. Gorsuch is a Westerner and has a rural (vice urban) perspective and is son of Ann Gorsuch, whose leadership of the EPA had, let’s just say, issues.

@Jack:

Let’s say you live in a condo in a Manhattan tower. On the ground floor there’s a restaurant. Would you not want the city to inspect – to take an example from above – the gas lines? How about the fire suppression equipment in the restaurant and the building itself? How about the elevators? Should the builder save money by dispensing with emergency stairwells? If you have to use one of those stairwells, do you think maybe there should be a reg requiring that door to be openable? If you step out onto your balcony and lean against the rail, would you not hope that had been inspected? Or, as you fell to earth would you pray to Ayn Rand for rescue?

New tech requires new regs. Example: drones. Is it OK with you if drones buzz cars on the highway? Is it OK if they hover just outside your window? If drones are used for delivery, would you like someone to look at the question of how much they can carry over people’s heads? Should I be allowed to strap a 12 gauge to a drone and zoom through the school playground?

Here in Vegas, Elon has managed to convince the powers that be that his subterranean tunnel filled with EVs driven by minimum wage kids, doesn’t need emergency exits. When you’re fleeing down a dark tunnel gasping from the toxic fumes of a battery fire, only to realize you’re trapped by the next Tesla, do you think maybe a regulation requiring a way out might be a good idea?

People like you, Drew, only have one belief: me me me, more more more, mine mine mine. Ideology makes people stupid. Greed makes them stupid and toxic.

@Grommit Gunn:

Someone should ask the Russian generals whose tanks have been stripped, often by the generals themselves, whether we should have a reliable inventory system for government vehicles.

@drj:

“This is pretty rich coming from a guy who overturned Roe.”

It’s even more rich coming from a person who voted to overturn Chevron. The entire point of Chevron was that Congress should not be expected to pass detailed laws, and instead should defer to the administrative agencies. The response to overturning Chevron would be to make legislation longer, not shorter.

So I did just read an interview of Gorsuch in the NY times. He comes across as a little myopic with anecdotes of the little people getting swept up by complex laws meant to prevent bigger companies from abusing all sorts of things. Yeah, there are laws to prevent animal cruelty at circuses that have apparently been applied to a self-employed magician who pulled his own pet rabbit out of a hat. Ok, that’s unfortunate that he had to go through a bunch of red tape, but do we want animals to be abused or not? To sound like a nosy do-gooder, yes I think “there oughtta be a law!”

But I do agree with Gorsuch that complicated laws, especially around taxes, tend to benefit the rich who can easily afford to find the loopholes. He doesn’t offer a solution other than burn everything down (I’m paraphrasing :). I don’t have a solution, but I’m pretty sure that’s not it.

Don’t fall for red herrings.

Sorry, but that’s one of those things people like to make a fuss over, and is almost entirely meaningless. If your macaroni is of a different size, you can still sell it, just not call it macaroni.

For instance, do you know in Mexico you cannot sell milk that’s not 100% cow milk, or fruit juice that’s not 100% juice?

See, that’s wrong. You can sell such things. Only not label them as milk or juice. Say you make a product that’s mostly milk, but contains vegetable fats as well. Then it’s labeled as “milk formula” (not an exact translation). Or apple juice that’s juice, water, and sugar. It can be sold as “apple nectar” (exact translation), or “fruit drink.”

There’s a problem with simplifying laws and regulations, namely that they may omit important aspects of the law. Also they may limit required or fair exceptions.

As to needs, before the pure food and drug act, the issue with adulterated foods, risky or dangerous preservatives, and snake oil drugs, was HUGE. I mean things like chalk and water with maybe some animal or vegetable fat passed as milk. That’s why we have tons of laws dealing with food.

He thinks there’s too many laws, but then overturns Chevron and pushes the major questions doctrine, both of which require more laws and more complicated laws.

What he really means when he says there’s too many laws is actually that he thinks there’s not enough impunity. He wants a world where people like him can do whatever they like and all the people harmed in the process have no recourse but to accept the injury.

Discussions like this drive me absolutely nuts.

I like to point out that laws and regulations don’t drop out of thin air…someone has either already abused the public trust, or it’s anticipated that they will. Period, full stop.

Mattresses have tags to ensure they conform to industry standards. Why? Because you don’t want a cut-rate mattress filled with old shirts and fleas, that’s why. It was VERY COMMON to use unsanitary filler material in mattresses before there were consumer protection laws.

Businesses will get away with as much as they can. As a baker, one of the top of mind examples was an effort a number of years ago by US bulk chocolate manufacturers to replace cocoa butter with vegetable oil. Why? Because they could separate the cocoa butter from the cocoa solids, sell that to the cosmetics industry for a lot of money, then use vegetable oil as a replacement in the edible chocolate. Now, because there were US regulations on what constitutes chocolate, manufacturers were required to essentially petition the FDA to make this change, which was posted to the Federal Register for comment. Companies that use chocolate, along with consumers, provided enough feedback that the change was not made (mass market US chocolate is allowed to use vegetable oils, but still must contain a certain amount of cocoa butter).

Greed, or maximizing earnings…no matter what you call it, businesses will push to the extremes. Regulations are necessary because of this.

Remember: If you’re an industry that doesn’t want to be highly regulated, don’t act like an industry that NEEDS to be highly regulated.

I wonder if it occurs to a “textualist” as Gorsuch proudly claims to be that part of the reason for the massive expansion of laws is way lawyers split hairs and how the Federalist Society in particular has made a fetish of fighting things not explicitly called out. Laws and codes can be a lot simpler when you allow juries and judges to exercise judgement and apply “common sense.” But we don’t want that.

Actually, I don’t wonder at all if Gorsuch realizes he and his entire legal focus is part of the problem.

@Stormy Dragon:

More laws and more complicated laws may be necessary but the Senate being what it is, we won’t get them.

Mission accomplished.

There is no legal philosophy, there are no principles. It’s all about impunity – for the right people, of course.

@Jack: so you’re quite happy to let the normal fire department deal with putting out a fire involving 1kg of sodium?

…guess we didn’t need that end of the Chemistry building anyway…

(Based off a story I heard from my father many many years ago.)

There is also the fact that we have 50+ different regulatory states that make trying to do business in several states a nightmare. Do we really need 50 different takes on all the different forms of insurance??? Ditto traffic laws, incorporation laws, and 50 different criminal regimes (including the court systems that all run differently)?

I understand that the holy founding fathers set it up that way and to be fair trying to deal with this on a national basis in the waning decades of the 18th century may have been too much of a hum dinger to manage, but today it would be much less so. As for the augment that the States are the laboratory of Democracy the only real difference I can see over the last 240 + years is slavery and no right turn on red. So I don’t buy that at all.

James wrote:

I was immediately struck by this as well. It seems like he wants to have it both ways.

100% this, which is also tied to another comment James made a little further down:

This in fact is why short bills are so difficult to write. As we have seen with the various Civil Rights acts, there have been a host of issues that have been raised in recent years as to what different aspects of the law “meant.” Heck, we’re still arguing to this day about another critical and short legal document: The Constitution.

Which gets back to the initial point, if you cut out the role of bureaucratic/expert interpretation then you need to make laws exceptionally detailed in an attempt to “future proof” them and that’s a really bad way to operate.

Gorsuch seems like a guy who throws away half the resumes for aspiring law clerks because he doesn’t want to hire anybody unlucky.

@Stormy Dragon:

I’m repeating your truth for emphasis.

I’d only add the adverse also applies. To wit, Gorsuch is perfectly happy with a world where people NOT like him can’t do anything that might not so much as inconvenience him that provides no recourse for his ilk to punish them.

@Rick DeMent:

States regulate insurance and it benefits consumers, particularly as it relates to homeowners insurance. Risks in California do not look like the risks in New York, the risks in Wisconsin don’t look like the risks in Oklahoma. You want to have regulators who understand the specific risks within a state, and how that risk ripples across different business lines and different buildings.

This same argument–that states understand the risks inherent to the state–holds true for health insurance (the health risks in Alabama are not the same as Massachusetts), and vehicle insurance (because weather is a factor, along with driving distances, so Texas is going to look different than, say, New Hampshire).

I’m not even sure how one would go about nationalizing insurance, it’s so, so tied to local factors.

If Gorsuch doesn’t want to deal with so many laws, he chose the wrong profession.

Not only is the world a more complicated place, but mankind really has been innovative in finding new ways to fuck each other over and we need laws to protect against that.

Until about 20 years ago, Washington State didn’t have a law against bestiality. Now we do. What do you think happened?

@Jen:

Can you elaborate on this?

People are people. The rates might be different based on locale and the relative risk (Florida has high sun, old people and Florida Man, while Washington has Enumclaw and horse related accidents), but what is covered and how should be the same. And Medicare is a national program that seems to work. The state-by-state implementation of Medicaid seems to be a genuine problem.

What am I missing?

@drj: @Rick DeMent: The Federalist Society explicitly wants to overturn what are known as the Slaughterhouse cases. The cases revolved around whether the state of Louisiana could legislate to force slaughterhouses to move from upstream of new Orleans to downstream. The problem being that when the river flooded, the streets were filled with offal and excrement. The 14th Amendment was written to ensure freed slaves and other Blacks were granted citizenship rights equal to anybody else. The slaughterhouses argued that the amendment meant they couldn’t be regulated any more stringently than slaughterhouses in other states. They lost. The FS, or more correctly the wants the Slaughterhouse decision overturned, in effect saying that 49 states would have to reduce their regulation of whatever to not exceed the most lenient state.

This is what the Federalist Society was astroturfed to do. To destroy the “regulatory state”. The gun and abortion stuff is just part of the populist facade. For gawd knows what reason WAPO (gift link) chose to publish a column by Mitch McConnell attacking Biden’s proposed Court reforms. “Originalism” is big o property rights. McConnell’s column comes down to saying the Kochtopus et al, via Lennie Leo and the FS, bought the Supreme Court fair and square and they’re entitled to keep it.

@Gustopher: Sure–first, part of what I was getting at were rate differences, so:

is definitely part of it. Medicare is premium-adjusted based on location, in no small part due to the existence (or absence) of provider competition in an area. There are also geographic cost factors to consider (costs of care are not identical across the country), along with the general health of the population. A state with a high percentage of Type 2 diabetics (e.g., WV), will need a health care system that looks different than, say, a state like Colorado. Basically, a state’s health care “mix” will impact its health care systems. A state with an aging population needs to have systems in place–including nursing home beds–that will differ from a state with a younger population.

I agree with you that what is covered and how should be the same–it’s taking into account what is needed (which will vary) that is what I’m trying to get at.

The Law!

@gVOR10: Hmmm… I’m not finding a disconnect in the owner of Amazon publishing a Republican screed attacking the regulatory state. Or did I misunderstand your comment?

@Franklin: “So I did just read an interview of Gorsuch in the NY times. ”

Oh, that was an interview! Explains a lot. I was wondering why I was watching one of their right-wing columnists give Gorsuch a blowjob in the editorial pages…

Sounds like Grampa on the Simpsons.

Grampa Simpson: Dear Mr. President, there are too many states these days. Please eliminate three. I am not a crackpot.

@drj:

Quite frankly, that is a really stupid comment.

@Grumpy realist:

Incoherent. But thanks for the effort.

@Michael Reynolds:

That’s just dumb, M Reynolds. Based on your comments I would have hoped for something more intelligent.

There is no need to go to schoolboy-style extreme arguments/examples. There is just a need to observe that law/regulatory expansion has far exceeded technological advance, and recognize regulatory capture and the tendencies of organizations.

I gather you are a writer. Apparently that’s beyond you.

@Jen:

Yeah, I’m not buying this (it’s the argument I would have used I guess). But you could say the same thing about anything. Hell, some states have 6 or 7 different and distinct areas where local knowledge is crucial, but we don’t break up big states over it. You would have to convince me that the various differences in regions and situations for insurance providers are fine being controlled by Austin but Washinton is a bridge too far. I think the idea that the expertise required to develop actuarial data can be done only at the state level is arguable.

I think the country would benefit if a lot of those things are, at the very least, more uniform or outright worked out on a national; level. Others need to be the same (traffic and different traffic laws can be the root cause of accidents, for example, the chartering of corporations is another).

50 different regulatory jurisdictions are an unnecessary tax on the people of the United States.

@Lucysfootball:

Well, we know one those states was Missouri. Grampa will be dead in the cold, cold ground before he ever recognizes it as a state.

People who talk about “too many laws/ regulations” always sound like Grandpa Simpson, i.e., a crank.

They can never point to more than just a few oddball regs that need to be trimmed, instead they just bluster and wave their arms.

Also, it should be pointed out, that a lot of the regulations that govern commerce were developed and promulgated by businesses themselves because hey, guess what, businesses want the safety and assurance that the products and materials they buy are safe and effective and not going to blow up or collapse when used.

Justice Gorsuch and his flunky:

I am offended that a Justice on the Supreme Court would reference this (or co-sign a reference of this), without pointing out that it is a violation of the 1st Amendment’s free speech language.

Or a likely violation, if they don’t want to be accused of prejudging a hypothetical case, but I think you would be hard pressed to find any dispute on the matter.

Overall, this is a nutter op-ed that is dancing around what he wants to say: now that we’ve gotten rid of Chevron deference, let’s get rid of laws too. Which laws? Dunno, but it’s not related to anything they are writing about.

@Michael Reynolds

@Jen:

@gVOR10:

It is really odd how people cannot grasp that a modern market capitalist economy absolutely requires legally bound and binding regulation to simply function.

Beyond that, it can be social-democratic (Scandinavia), capitalist welfarist (US, Germany, UK under several parties), or “state directional” (Japan, Korea, France).

But all serious parties realised in the late 19th century, classical liberalism was entirely inadequate to operating a functional urban-industrial society.

FtloG, that’s why the Tories in Britain supported the Factory Acts, the Liberals sgifted from laissez faire doctrine, the Republicans in the US adopted “progressive” regulation and “antitrust”, etc etc.

@Jen:

@JohnSF:

I’ve chanced upon a lot of late XIX to early XX century history lately, in particular US history of the period. It boggles the mind what kind of things businesses got away with absent specific laws and regulations.

You see a lot of things like adulterated food, child labor, dangerous and unsanitary working conditions, low wages, unsafe products, excessive pollution, etc.

Of course, businesses boomed and made lots of money. We call part of that era the gilded age.

I don’t quite see the same thing happening today, but it’s close. People do learn from history. Today, big corporations try to find moral justification for their excesses. They’re job creators. They’re focused on shareholder value. And so on.

It took two world wars to really change things, and the changes didn’t stick.

@JohnSF:

There is a whole history to it. In brief, the way I think about it, there was a concerted campaign by manufacturing associations and other capital-oriented organizations to persuade the public that government is intrinsically bad.

This, rather than turn the public against the government completely, switches the default from petitioning the government to solve problems to viewing the government as being the problem.

@Rick DeMent: I am not sure what you are arguing here…that the risks in California (earthquakes, wildfires) aren’t different from Texas (hail, hurricanes)? Or are you saying that it doesn’t matter what the regulatory bodies understand about how those risks affect localities?

It seems really obvious to me that different weather events impact states in various ways, and insurance drills down to the zip code level so I am trying to comprehend what your objection is to state regulatory authority.

That doesn’t even touch things like the use of credit scores in the determination of premium costs, which is allowed in some states and not others.

@just nutha: You’re right. I had in mind WAPO of reputation, not the Quisling WAPO of the last couple years.

Having not read the post, I can only say our not so supreme court justices are out of control.

The dude cited the length of the ACA for his argument. The ACA created a whole new federal structure, how could it not be long. And most of the provisions in it are things that ordinary citizens don’t have to know about. Insurers need to know about them, but they can pay people to read it and figure it out. The cost of hiring people to do this is probably not even material to what they do – it’s pretty much negligible.

But no, it’s terrible. I’m sure Gorsuch doesn’t like the ACA, because what conservative does? How could that legislation do its job without being that long, though?

Lord, his credentials suggest he is not stupid, but man, this is a dumb argument. I expected more from him.

@Kurtz:

The odd thing is that in Europe, Japan, Korea etc most business’, large and small, have realized a stable regulatory and market-upholding legal system is benefial, both commercially, in avoiding monopolistic dominance and/or a “race to the bottom”, and politically, in avoiding mobs with pitchforks and torches, tar and feathers.

Even in the US that seems to be the consensus.

It’s just for some reason in the US the fringe of anarcho-capitalists and disgruntled gougers retain considerable wealth and political heft.

Exactly why is a bit puzzling.

Perhaps relating to the political sociology of reaction to the New Deal and the post-war state?

(Racial factor?)

While other countries had moved to state regulation of markets half a century earlier?

Dunno.

It’s an area of comparative history that needs a more heavy-duty mind than mine to analyze.

@Jack:

I think you know deep down that the regulations aren’t made just to slow people down. To what end? It makes no sense. I know it’s dogma to the invisible hand people, but it’s really just a willful misunderstanding or a childish lashing out over a disagreement on the role of government.

Now, if you had pointed out some specific case like slowing down the decimation of forests, okay we can discuss whether that is slowing “productivity,” but most any tree hugger would be able to win that argument in their sleep.

The fact is, almost every regulation is a response to something negative that has actually happened. So the question is, how would the free market extremists solve problems? As I’ve mentioned occasionally, I was a libertarian when I was young and naive, so I already know the answer.

@Jack:

@Franklin:

If the problem is “unproductive people”, you might want to look at the socio-economic conditions that prevent a fully productive/creative society.

Things like educational failure, debt traps, conditioned limitation of aspiration, lack of secure employment, etc etc etc.

There seems no reason to suppose an inherent division between productive and unproductive.

Basing society on such premises was the fatal flaw of most pre-modern civilisations: tribal, ancient Middle Eastern, Classical, Medieval feudal, Islamic, classical Chinese, Indic caste, etc etc.

But assuming that, as of now, a non-regulated economy will produce Utopia seems to me naive.

Somalia is almost entirely free of governance; much good has it done it.

@Gustopher: Which brings me to my original question when I first read the post*:

To what end have he and his former flunky/minion written this piece? Whose agenda are they promoting? What do they want done?

*Haven’t looked up the article. I’m tired of The Atlantic suggesting that I need a subscription. If I’d wanted to keep my subscription, I wouldn’t have cancelled before my auto renewal was triggered at year’s end.

@Jay L Gischer: I suspect he’s making the argument (again, what’s the agenda for the piece?) to stupid people–MAGAts. There’d be no purpose in wasting an intelligent argument on MAGAts; they wouldn’t understand it, and it wouldn’t enrage them to action as a dumb but resonant (the gubmint is FWKT!!!) will.

Why this appears in The Atlantic is another point altogether. It may be for rebroadcast on RWNJ talk radio as the voice “of intelligent people who agree with us,” but that’s just speculation.

@JohnSF:

Except that those aren’t bugs here; they’re features.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: The Atlantic prides itself on publishing all viewpoints (as long as they are written well, which I think refers to grammar and style, not logic and cogency). So they do this.

Meanwhile, I’m wondering about the seemliness of a Supreme Court Justice writing an op-ed using a classic Republican talking point. I mean, they supposed to be above politics, right?

It’s weird. Both Kavanaugh and Gorsuch went to the same high school, but I always took Gorsuch to be the serious one, and Kavanaugh the party-boy political soldier. I may have to rethink that. But maybe Kavanaugh is savvy enough to understand how bad it looks.

I read the article, assuming that since the man is on the Supreme Court, at least he’d say something thought-provoking, even though I assumed I’d disagree with it. Maybe he’d change my mind. Instead, I’m just left with a line from “Billy Madison”:

“Mr. Madison, what you’ve just said is one of the most insanely idiotic things I have ever heard. At no point in your rambling, incoherent response were you even close to anything that could be considered a rational thought. Everyone in this room is now dumber for having listened to it.”

Especially given that he was one of the people who ended Chevron, and made up the Major Questions doctrine, in which the Supreme Court said that we need more laws, not fewer.

I do agree with the issue of laws not being easily accessible; it’s why I donate to Public.Resource.org.