United States Less Democratic Than it Used to Be

Multiple indicators point to a decline in the representativeness of the American system.

In this morning’s open forum, OzarkHillbilly draws our attention to a Guardian report headlined “US sinks to new low in rankings of world’s democracies” that is simultaneously worth taking stock in and deeply flawed.

The report is based on the latest release from Freedom House, the granddaddy of these indices.

The US has fallen to a new low in a global ranking of political rights and civil liberties, a drop fueled by unequal treatment of minority groups, damaging influence of money in politics, and increased polarization, according to a new report by Freedom House, a democracy watchdog group.

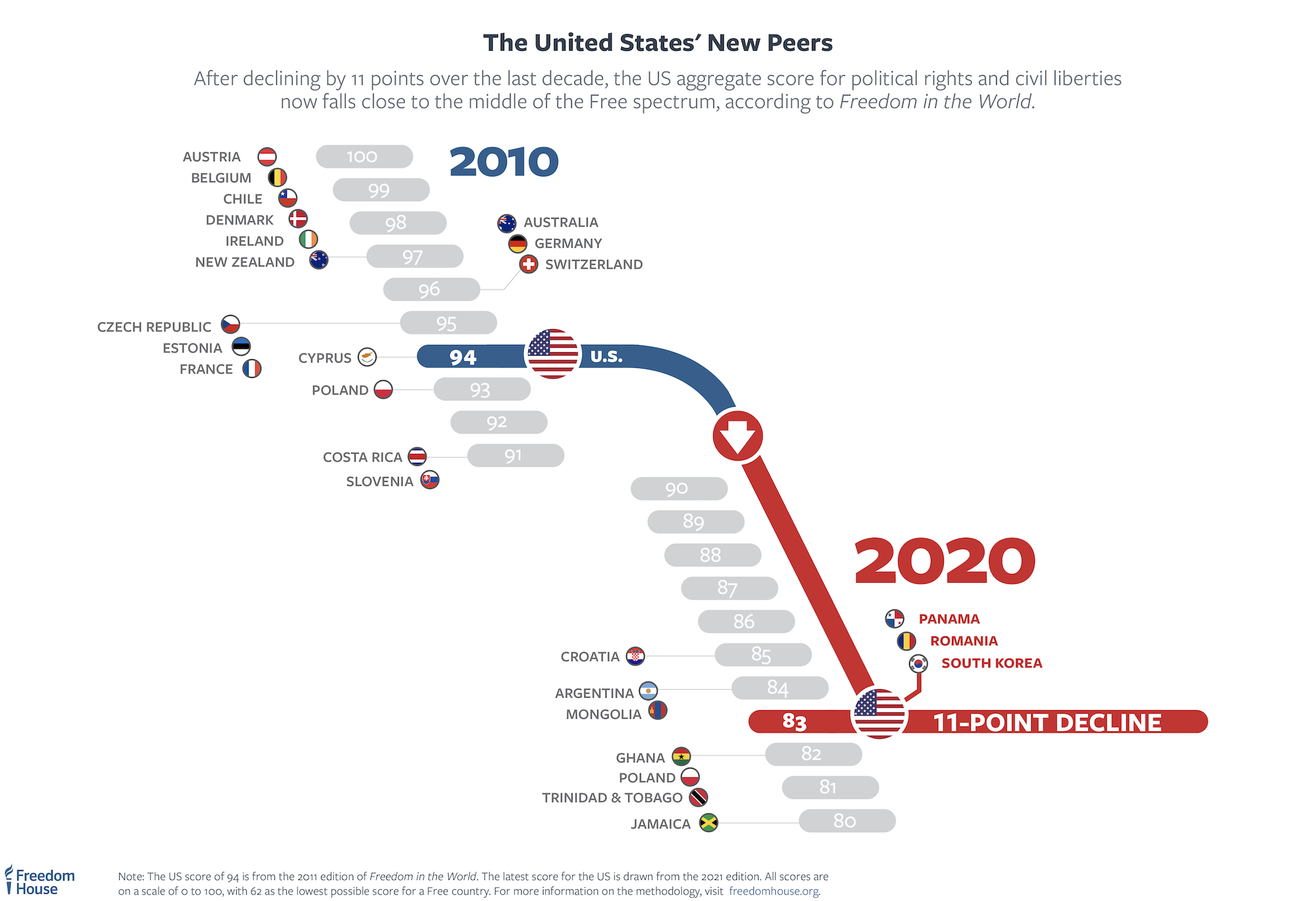

The US earned 83 out of 100 possible points this year in Freedom House’s annual rankings of freedoms around the world, an 11-point drop from its 94 ranking a decade ago. The US’s new ranking places it on par with countries like Panama, Romania and Croatia and behind countries such as Argentina and Mongolia. It lagged far behind countries like the United Kingdom (93), Chile (93), Costa Rica (91) and Slovakia (90).

That there are new threats to American freedom since the last rankings were released is quite plausible. That we’re behind any of these countries, aside from maybe the UK, however, is laughable. Indeed, they have us sandwiched between Mongolia and Ghana—and just two points above Poland, which has descended into autocracy:

How do they justify this?

“Dropping 11 points is unusual, especially for an established democracy, because they tend to be more stable in our scores,” Sarah Repucci, Freedom House’s vice-president for research and analysis, told the Guardian. “It’s significant for Americans and it’s significant for the world because the United States is such a prominent, visible democracy, one that is looked to for so many reasons.”

While Freedom House has long included the US in its global ranking of freedoms, it traditionally has not turned an eye inward and focused on US democracy. But this year, Repucci authored an extensive report doing just that, a move motivated by increasing concern over attacks on freedoms in the US.

The report details the inequities that minority groups, especially Black people and Native Americans face when it comes to the criminal justice system and voting. It also illustrates that public trust in government has been damaged by the way rich Americans can use their money to exert outsize influence on American politics.

And it points out that extreme partisan gerrymandering – the manipulation of electoral district lines to boost one party over the other – has contributed to dramatic polarization in the US, threatening its democratic foundations. Gerrymandering, the report says, “has the most corrosive and radicalizing effect on US politics”.

So . . . these issues are real. But they didn’t emerge last year. Racial inequalities in criminal justice have certainly been highlighted by recent events but they’ve been with us since the beginning of the Republic and are surely better than they were in the 1970s, when the report launched. And, yes, gerrymandering has gotten more sophisticated. But the current set of Congressional districts were drawn a decade ago; literally nothing in this regard changed in between this year’s report and last to justify a radical drop.

What Repucci and company have done here is not an objective ranking but the use of their platform to take an ideological stance. Which is just fine—indeed, I largely agree with the stance—so long as we understand what we’re looking at.

Nor am I attacking the integrity of the project because I don’t like how they’ve ranked the US this year. These flaws are well-documented.

Back in 2017, political scientist Sarah Bush (then at Temple, now at Yale) wrote a piece titled “Should we trust democracy ratings? New research finds hidden biases.” for WaPo’s Monkey Cage. The research was her own:

[A]s I show in a new article, these rankings are not only rating democracy but also defining democracy for certain audiences. Commonly used ratings can tell us as much about the rater as the countries being rated.

There are more than 180 ratings that evaluate country performance in various issue areas, ranging from human rights to economic policy to democracy. These scorecards influence countries in significant ways, often prompting them to improve their behavior.

One of the first organizations to develop a rating system for states was Freedom House, an American nongovernmental organization. Freedom House launched its “Freedom in the World” report in 1972. Since then, the organization has reported on countries’ political rights and civil liberties — essentially, their levels of democracy — each year. In these reports, countries are given ratings on a seven-point scale and overall assessments of “free,” “partly free” or “not free.”

[…]

Although these rankings draw considerable attention in international politics, it is not immediately obvious why certain scorecards have become trusted and widely used.

When Freedom House began issuing its reports, it used methods that many academic critics found lacking. In the 1970s, one social scientist — Raymond Gastil — essentially produced the reports and ratings “alone,” although his wife, Jeanette, provided uncredited assistance. A team took over in 1990, and today the ratings use a much more transparent methodology, though critiques remain.

Gastil himself resisted the idea that the ratings were a precise or scientific exercise. In 1990, he described his approach as relying on “hunches and intuitions” and “a loose, intuitive rating system for levels of freedom or democracy, as defined by the traditional political rights and civil liberties of the Western democracies.”

[…]

Scholars, policymakers and citizens all want to know how democratic countries are. In the United States, an ongoing debate considers whether or not the country is exhibiting signs of democratic erosion.

Choosing whether and which democracy rating to use requires a judgment about the underlying concept in question. To what extent does democracy depend on the quality of elections vs. factors such as political trust?

Although country rankings give the appearance of neutrality, they involve subjective decisions about how to define key concepts. The most influential ratings often are powerful precisely because they reflect the value judgments of the powerful.

Journalist and democracy activist Ilya Lozovsky looked at the index in January 2016. The subhed summarizes his thesis admirably: “Freedom House’s index of freedom in the world is flawed — but the story it tells is indispensable.”

Over the last decade, political scientists have produced a wealth of literature documenting the annual reports’ biases and methodological problems. Their conceptual basis is flawed; the data collection is opaque; the results are overly simplified; Freedom House has a neo-liberal bias. Jay Ulfelder, a political scientist and independent consultant, has convincingly disputed Freedom House’s overall findings — that freedom in the world is steadily declining — for two years in a row.

And yet, flawed as they may be, Freedom House’s ratings still matter. They are a crucial tool for pro-democracy activists. They drive dictators crazy. And, perhaps most important of all, they get worldwide attention. The reason is simple: Unlike the number crunchers, Freedom House knows how to tell a story. And in the world of international human rights advocacy, one good story is worth a thousand finely tuned disaggregated indicators.

There is good reason to treat the critics’ complaints seriously. Start with the obvious: how do you assign a number representing an “amount of freedom” to every country on earth? One social scientist — who has worked on several Freedom House reports — put it quite simply: “The numbers are bullshit.”

The problem is that each country’s scores aren’t really a measure of anything concrete — they are, in essence, assigned by feel. The people Freedom House hires for this job are generally experts on both the country in question and on democratic processes, so it’s not a question of competence. Rather, the problem is that awarding 0 to 4 points for each of a country’s 10 political rights indicators and 15 civil liberties indicators is, by definition, an arbitrary exercise.

Take just one of these indicators, which are phrased in the form of questions: “Is there open and free private discussion?” So what’s the score going to be? Two? Or three? What, exactly, does either choice mean? And are the dozens of researchers assigning scores to other countries interpreting the scale in the same way? The problem is compounded by the fact that Freedom House doesn’t release these subscores individually; only in the aggregate. As a result, “scholars laugh at how bad the measure is,” said the social scientist (who declined to be named to preserve a good relationship with Freedom House), adding that graduate students who try to use the scores in a study get a “polite but firm talking-to.”

But there’s a more fundamental problem that no review committee can address. No matter how carefully or systematically the scores are assigned, first you have to decide what you’re going to measure — and on this there can be no widely accepted consensus. Do you think “free trade unions and peasant organizations” and “effective collective bargaining” are as important as an “independent judiciary”? Freedom House does. But when these subjective judgments are collapsed into just a few numbers — which are then treated as authoritative, impartial measures of something called freedom (or democracy; the distinction is often blurred) — the result is something of a conceptual mess.

There’s a better way:

To try to resolve these issues, or at least address them in a different way, a host of alternative indices have been devised in recent years. The problem is that, unless you’re a democracy scholar, it’s a safe bet you haven’t heard of any of them. Perhaps the most ambitious is one of the most recent: faced with the impossible task of creating a single scientifically rigorous measure of freedom, the V-Dem index doesn’t attempt to do so at all. Instead, it divides “democracy” into seven high-level principles, each of which are subdivided into about 400 minute and highly specific indicators with precise definitions and scoring guidelines, all of which are made publically available. This makes this index much more useful to academics than the Freedom House scores, which, in any event, were always meant more for advocacy than research.

Alexander Cooley, a political scientist who has recently co-authored a book critiquing the spread of international rankings, has a broader criticism. Why, he asks, do we need to “delegate our understanding of a particular country’s democratic trajectory to Freedom House? Why is it that we let these indicators and these scores about countries be a shortcut for our own judgment for grappling with these issues?”

Lozovsky answers his own question:

There’s a simple answer. It’s because people who are not democracy scholars (including diplomats and policymakers) can only pay so much attention to complex topics outside their areas of expertise.

In their most extreme act of simplification, Freedom House’s reports boil down a host of complicated phenomena into a single value for each country: “Free,” “Partly Free,” or “Not Free.” Yes, it’s a shortcut — but people need shortcuts.

Journalists need them when they’re trying to understand a country on deadline. Activists need them when hammering home an important point to a bored politician. Diplomats need them when pressing a reluctant government to open the window of freedom just a crack wider. And, in our schizophrenic, distracted age, we all need them to make sense of just what in the hell is actually going on.

The most effective shortcut of all is a story — and this is where Freedom House really excels. Unlike any of the other indices, Freedom in the World comes with an overview essay that paints a portrait of what happened over the previous year. The full version of the report also includes a detailed narrative for each country, noting the most important developments and providing context for the raw numbers. The reports are illustrated with colorful charts and maps. And with the full might of a 75-year-old organization behind them, they reach audiences around the world. A document published by V-Dem itself notes that the Freedom in the World index gets almost 367,000 Google hits. The next-most popular, Polity IV, gets just a fifth of that number, and none of the others come close. It’s telling that, while producing these reports constitutes just a small fraction of Freedom House’s budget, they are, by far, the main thing the organization is known for.

That’s largely right, I think. So long as what we understand what the Freedom House index is—the work of an advocacy group promoting a particular version of democracy—it’s fine. When a country makes a major move up or (especially) down the rankings, it’s going to get attention. To the extent you agree with Freedom House’s view of democracy—and I by and large do—it’s great that it draws attention to injustice, corruption, and repression.

The problem is that it’s often taken by journalists and others to be a work of social science. Failing to understand that Repucci is trying to send a message with her massive downgrading of the United States and credulously reporting that we are now behind Costa Rice and “on par” with Mongolia is a disservice to readers.

Aside from the propaganda value that Freedom House’s accessibility provides, it’s better to look for trends across the various indices rather than at any one. And here’s the thing: The United States is simply becoming less democratic across any number of them.

Back in January, the Center for Systemic Peace, which publishes the gold standard Polity database, announced:

The USA has dropped below the “democracy threshold” (+6) on the POLITY scale in 2020 and

is considered an anocracy (+5) at the end of the year 2020.Users of the Polity data series should be aware that Polity measures patterns of authority demonstrated and observed in political behaviors involving interaction events between and within state and non-state entities. Polity measures political practices rather than proclamations. In 2016, CSP changed the coding for Political Competition in the USA to Factional (or polarized) Competition; this coding change dropped the USA’s POLITY score to +8. According to the PITF Global Model, this change to “factional competition” placed the USA at high risk of impending political instability (i.e., adverse regime change and/or onset of political violence). In 2019, CSP changed the USA code for Executive Constraints from 7 to 6 due to the executive’s systematic rejection of congressional oversight. In 2020, the coding for Executive Constraints fell another two points due to the executive’s systematic purge of “disloyalists” from the administration, forceful response to protest, villification of the main opposition parties; and undermining public trust in the electoral process, reducing the USA POLITY score for 2020 to +5 (anocracy).

The Economist dropped us from “democracy” to “flawed democracy” just after President Trump’s inauguration, explaining:

AMERICA, which has long defined itself as a standard-bearer of democracy for the world, has become a “flawed democracy” according to the taxonomy used in the annual Democracy Index from the Economist Intelligence Unit, our sister company. Although its score did not fall by much—from 8.05 in 2015 to 7.98 in 2016—it was enough for it to slip just below the 8.00 threshold for a “full democracy”. It joins France, Greece and Japan in the second-highest tier of the index. The downgrade was not a consequence of Donald Trump, states the report. Rather, it was caused by the same factors that led Mr Trump to the White House: a continued erosion of trust in government and elected officials, which the index measures using data from global surveys. In total, it incorporates 60 indicators across five broad categories: electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, democratic political culture and civil liberties.

Now, to be clear: France and Japan are pretty damned democratic by world historical standards. But, yes, we’re more fractured than we have been in generations and it has damaged our democracy. So, no, we’re not Mongolia. We’re not anywhere close to Mongolia. But we’re not the World’s Greatest Democracy anymore, either.

Updated to add the graphic from Freedom House.

Thanx James. I posted this mostly as a reaction to recent efforts by the GOP to put even more barriers up between certain American citizens and their right to vote, which the article didn’t even refer to.

It seems very plausible to me that America is behind Costa Rica. People travel to Costa Rica and actually like the normal life they see. Point me to any person who goes to America and comes away impressed with American health care or public transportation. You scratch the surface of any normal thing in America and you find horror story after horror story. And instead of trying to make things better, which a normal society might try to do, American democracy spends all of its time trying to appease white people who just can’t stop voting for the party that says real America will always be #1.

Just to be contrarian: perhaps America’s score had been artificially inflated by reputation, and this is a correction.

Also, the electoral college being out of whack with the popular vote is a lot more noticeable now than a decade ago.

The Senate and the filibuster are getting a lot of attention as flaws in our democracy. Digby has a post up extensively excerpting an article by political scientists Hacker and Pierson. They’re taking McConnell and others’ bluster as a sign of real fear that the Ds will remove or modify the filibuster. ‘By God, we’ll obstruct everything if you dare take away the tool we use to obstruct everything now.’

They point out the asymmetry, that Ds want to do things while Rs want only to pass tax cuts, which they can do under reconciliation, and appoint judges, for which McConnell killed the filibuster.

They talk of the workings of the Senate being opaque to most voters. Commenters here have some level of understanding of the filibuster. Less engaged voters couldn’t tell you who their Representative or Senators are. McConnell failed in making Obama a one term president, but was a realistic plan, and he’ll try it again with Biden. Voters only see that nothing is being done, but as the current workings of the filibuster are largely hidden, they blame the most visible office holder, the President. Obama was able to do anything only because Ds very briefly had 60 votes in the Senate.

They demonstrate why reverting to a talking filibuster would be a huge improvement. They depend on the anonymity of the current filibuster, a talking filibuster would force them to put a Republican face and Republican name on their obstruction. Some increment of voters will punish GOPs for their obstruction instead of punishing Biden and the Ds for it.

Digby’s post is a bit long, but well worth reading. Or the whole Hacker and Pierson piece at The Atlantic.

I ask this sincerely – what’s wrong with Mongolia’s democracy that you would claim we aren’t anywhere close to them?

I know very little about Mongolia’s current political situation, but I couldn’t find any news reports of citizens storming their capitol or their governing party blinding protecting their leader from charges of corruption and incompetence. Their democracy is quite a bit newer than ours, but do you have information that indicates they are as anti-majoritarian as the US? They don’t have our history of slavery, so do you discount that they don’t have as much systemic racism as we do?

As Gustopher notes, as the world’s longest standing democracy, couldn’t we have been graded on the curve in the past and that’s harder to do now that the curtain has been pulled down? Say what you will about the various biases in these indices, America has not been all that for some time now. And, I submit, our national knee-jerk defensiveness when this is pointed out is one of the reasons we’ve taken so little corrective action to address our decline.

This really sounds like a bit of implicit western-white bias. How much do you know about the politics of Mongolia, Chile and Costa Rica? Or even Slovakia, the backwards cousin of the Czech Republic, where the people are white, but not so western?

The US has done a better job of promoting democracy than practicing democracy, so it wouldn’t surprise me if some of these countries were doing better than us. Parliamentary democracy is pretty much the model used by a lot of countries, and generally better than our weird and broken system, so… yeah, the newer democracies will surpass us.

This is either an ominous warning, or a sign that the dude isn’t updating Poland’s score regularly.

I do applaud your trolling of Teve with the lack of apostrophe. If you write “were a Republic, not a Democracy” you can troll Teve and Steven Taylor at the same time!

Yeah, those other countries didn’t have a violent mob try to disrupt the transfer of power resulting from an election. They don’t have anti-democratic institutions like the Senate and the Electoral College, either. They don’t have a structure in the House of Representatives where one party needs to get 55 percent of the vote to get 50 percent of the seats, unless they lean into gerrymandering as hard as they can.

So I think a drop in our ratings is entirely appropriate.

Setting various point systems aside, we are clearly less democratic, less representative. For example, we did not used to have presidents refuse to accept elections, or send mobs rampaging through Congress. And the GOP is desperately trying to stop people voting. Yes, they’ve been against people voting for a while now, but they didn’t used to call people from the Oval to demand the overturning of an election. None of this is normal. A cult of personality is not democratic.

@Gustopher may be right that we got points we didn’t deserve in the past, but because we are who we are we deserve to be graded harshly. This isn’t Venezuela, FFS, we’re a 200 year old democracy with money and power and a well-fed if not well-educated population facing problems that are pitifully by comparison with most of the world.

We’re not just less democratic, we’re pathetic.

@Modulo Myself:

Those are not measures of democracy by any reasonable definition.

@Scott F.:

It’s essentially one-party rule, with multiple competing institutions but dominated by a quasi-dictatorial president who has all but removed the judiciary as an independent actor.

@Jay L Gischer:

It was an awful spectacle but it was a relative handful of people that posed zero actual threat to the transfer of power. It was a riot.

These have literally been features of our Republic since its founding. I think it’s reasonable to downgrade us vis-a-vis some other democracies for these issues. But it’s absurd to downgrade us via the 2011 version of ourselves.

@Michael Reynolds:

Absolutely! And, again, I think Freedom House calling attention to this is useful. But the thing is: they’re literally comparing us to Venezuela using the same scale. If they’re doing that, then the numbers should add up.

@gVOR08:

I’m not sure I know my Senators and Representative. They’re all Democrats, I know that… Patty Murray, Prialla(?) Japal(?) and another woman Senator, I think.

(google, google)

I forgot Maria Cantwell’s name, and I butchered Primala Jayapal’s name. Of them, I know Patty Murray wears sneakers or something, and that Rep. Jayapal is pretty good on civil rights, but honestly, none of them really speak to me other than being reliable Democrats.

@Gustopher: 😛

I actively try not to get annoyed at this, and (Condescending rest of sentence deleted)

@James Joyner: James, they had to delay the counting of electoral votes for several hours. This seems pretty darn significant to me. I mean, what if they had to delay for a couple of days. One could imagine people thinking that there are “possibilities” and “contingencies”.

Not to mention several people within that chamber endorse the idea that the election was stolen. If you believe them, that’s a downgrade to our democracy grade, and if you don’t believe them, it’s still a downgrade.

I don’t have time to really comment, but I will say this as it pertains to the US and these indices, especially FH: we were almost certainly ranked higher than we deserved in objective terms for a while, i.e., our starting spot before the 11 point drop was almost certainly inflated (because, as James notes, a lot of our anti-democratic features are not new).

FWIW, here’s some time series data for the Polity index over the past few years for some countries that might be intuitively easy to compare the US to. Hugely negative scores like Afghanistan and Syria were left off the list. Complete historical data are available (though only through 2017 for most countries) at their website. That’s why Poland and Hungary don’t look bad yet.

year 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Australia 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 n/a n/a

Brazil 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 n/a n/a

China -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 n/a n/a

Germany 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 n/a n/a

Hungary 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 n/a n/a

Israel 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 n/a n/a

Korea North -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 n/a n/a

Korea South 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 n/a n/a

Mexico 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 n/a n/a

Pakistan -5 2 5 5 6 6 6 7 7 7 7 7 7 n/a n/a

Poland 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 n/a n/a

Russia 6 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 n/a n/a

Saudi Arabia -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 -10 n/a n/a

South Africa 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 n/a n/a

United Kingdom 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 8 8 8 n/a n/a

United States 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 8 8 8 7 5

Venezuela 5 5 5 -3 -3 -3 -3 4 4 4 4 -3 -3 n/a n/a

Vietnam -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 -7 n/a n/a

@James Joyner:

See, Mongolia is a Republic and not a Democracy. [sarcasm, not aimed @james]

It does seem interesting that the party that the party that started two wars, using in part of the justification, the promotion of democracy, should be seeking to stifle democracy at home.

Something jumped out at me:

Sadly that isn’t the case. Thanks to factors like mass incarceration, three-strike laws, the use of police in schools, the racially disproportionate impact of drug laws, over-policing, and many other factors (including the expanding long term impact of having a record and how that limits job and housing possibilities) things are actually worse than in the 1970’s. And that’s with significant steps that have *decreased* racial disparities from their peak in the early 2000s.

To be clear, the above should not be taken to say that the Criminal Legal System was good for Blacks and other POC in the 1970’s. It’s just that it got much, much, MUCH worse during the 80’s, 90’s, and early 2000’s.

@mattbernius:

Thanks for pointing this out. I think that a lot of white males (including myself) default to thinking that everything has been getting steadily better for everyone, with respect to justice and equality and representation — just maybe not fast enough. As you note, that isn’t true. Progress is not only not automatic, it’s not monotonic. Backsliding happens. That’s a big part of what is so pernicious about the GOP demonization of accurate reporting of both history and the current state of affairs as anti-American.

@DrDaveT: i upvoted you for ‘monotonic’.

@mattbernius:

@DrDaveT: Yes, that’s fair. I was thinking in terms of the things that led to BLM, not the other, systemic issues. While we’re far more aware as a society of the degree to which Black citizens are afraid of being assaulted by police, they’re almost certainly objectively less in danger now than they were in 1971. But, yes, we’ve likely undone the benefits that accrued from decreased racism among cops (and, indeed, the hiring of Black cops) by over-policing, etc.

@DrDaveT: Interesting. Although the pictograph is from Freedom House’s current numbers, not Polity’s. (In fairness, FH dropped Poland, too.)

So many of these discussions remind me of Sorkin’s opening sequence to newsroom.

That speech remains with me yet

@James Joyner:

(Sorry, I just can’t resist.) Wa! For a brief moment, I thought you were writing about the Senate.

@James Joyner:

Yes, but I believed you when you said that Polity’s index is the gold standard, and that FH’s is… not. I thought it would be interesting to see what they were saying about the relative standing of the US over time.

@DrDaveT: Ah. Gotcha.

@James Joyner:

Oh, James.

The flaws in these attempts to quantify complex human systems is neither new or surprising. I don’t really have anything to add to that.

Rather, I’ll just register my objection to the tendency to use “freedom” and “democracy” as interchangeable or synonymous terms or assume that they are linearly related.

@DeD:

Thank you for saying that better than I can.

@DeD:

What @Mattbernius said.