Yes, Presidential Approval Matters

An explanation to a question you likely weren't asking.

FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley explains “Why You Should Still Pay Attention To Joe Biden’s Approval Rating,” even though, if you’re reading OTB or FTE you likely hadn’t considered doing otherwise.

His premise:

When it comes to presidential approval ratings, the days of big swings in opinion and sky-high ratings are gone.

Consider that former President Donald Trump’s approval rating mostly hovered between 40 and 45 percent, earning him the distinction of having the steadiest approval rating of any president since World War II. In fact, one way Trump embodied the nickname “Teflon Don” so early was by how little his approval numbers moved in response to the many controversies swirling around him.1 Former President Barack Obama also saw small fluctuations in his approval numbers.

Well, sure. We’re hyperpolarized and sorted in a way that we haven’t been in decades. But that is a fact of life that, unless changed, limits how much Presidents can get done.

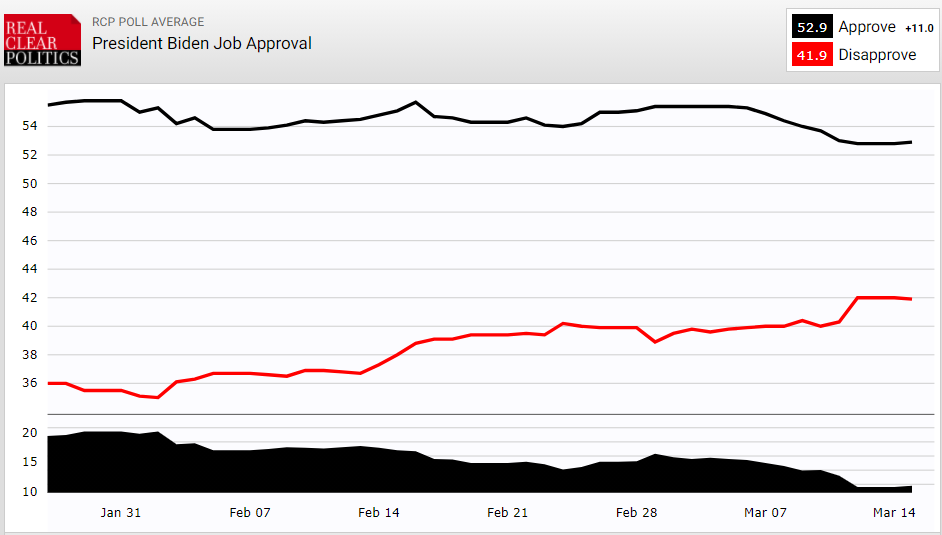

Further—and this is why I’ve been paying attention to the polling numbers—we can see that President Biden is considerably more popular than his predecessor. According to the RealClearPolitics polling average, Biden’s approval is at 52.9% with a disapproval of 41.9%.

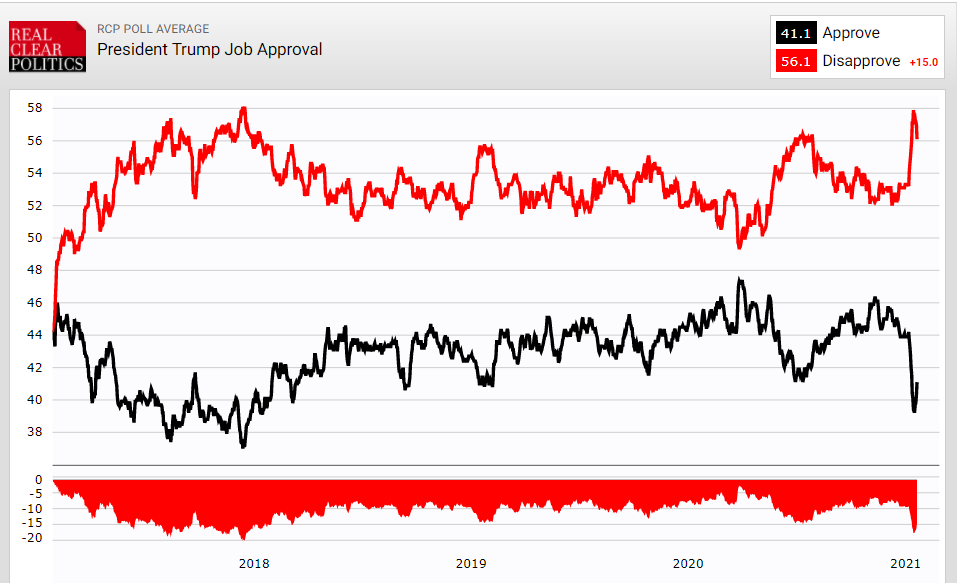

That’s significantly more popular than Trump, who never got above 46 percent approval and spent all but the first few days of his administration underwater:

Surely, that tells us something about how the public perceives their comparative performances, notwithstanding that most are viewing it through partisan lenses?

You’d think. But Skelley instead compares it to other eras:

It’s early yet, but President Biden’s initial approval marks aren’t all that impressive, either. Or at least that’s true when compared to past presidents’ ratings in the first few months of their presidency, often referred to as the “honeymoon” period. (According to FiveThirtyEight’s presidential approval tracker, 53 percent of Americans approve of Biden’s job performance,2 whereas at this point in the presidency, most new presidents’ approval ratings have usually been closer to 60 percent.)

Well . . . okay. But looking at Skelley’s own charts, we see that this hasn’t been true in a long time. Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Ford, and Carter all had serious “honeymoons.” In that era, only Nixon enjoyed less than 70 percent approval. Beginning with Reagan in 1981, none started with even 60 percent approval until Obama—who only barely exceeded that before slowly receding to the 50-50 mark by about a year in.

Regardless, approval is approval. If half the country doesn’t approve of a President’s job performance because they’re partisan poopyheads not giving him a fair chance . . . they don’t approve of the President’s job performance.

Which, after that bizarre setup, is more or less Skelley’s position.

So if the new normal is presidential approval ratings that don’t change all that much, is it time to abandon them?

Not so fast. On the one hand, we do need to recalibrate our expectations of presidential approval ratings. They’re just not going to move that much in our hyper-polarized political climate. But that doesn’t mean approval ratings aren’t a useful window into how the public broadly views a president’s performance. Or that they can’t still signal a change in political fortunes. And once we move past the presidency, approval ratings of other American leaders, such as governors, see wider ranges of support largely because partisanship isn’t quite as baked in at the state level.

Which just tells us that, as much as we’ve nationalized and presidentialized American politics, a lot of politics remains local. California remains a one-party state who will vote for the Democratic nominee in 2024 absent circumstances so extraordinary that I’m unable to conjure it. But Democrat Gavin Newsom’s management of the COVID crisis has nonetheless been wildly unpopular. Almost certainly even moreso with Republicans—but unpopular all the same.

The rest of Skelleys’ post digs further into the ways in which Presidential approval ratings are relatively more bounded than they once were. Which is perfectly interesting in a polling geek or political science sort of way. But the answer to the opening question remains self-evident.

@James Joyner

That’s just not true. He still remains in net positive territory on his handling of the pandemic, and still has a positive net approval rating.

Here would have been a more accurate statement: But Democrat Gavin Newsome’s management of the COVID crisis has nonetheless been wildly unpopular among the right wing nutjobs in the state.

As Eddie said, Newsom’s approval ratings aren’t that bad. He’s down from the 60+ % he had in May, but still right around 50%. His handling of the pandemic in it’s early stages earned him high marks. He’s back to about where he was before.

To the larger point, even if we only consider approval from the president’s own party, those numbers do tell us how well he’s doing with the voters whose support he needs. You know that’s something every politician will keep a close eye on.

@EddieInCA: @Kari Q: Fair enough, although he’s still danger close in a recall effort in an overwhelmingly-Democratic state.

@James Joyner:

The rules for a recall in California mean that a small group of highly passionate voters can trigger one. It only requires 12% of voters to sign the petition to trigger a recall. The election will probably occur because Republicans really hate him, but that doesn’t mean California voters generally think it’s a good idea.

That’s a good illustration of how the term “Teflon” when applied to political leaders has been stretched to the point of meaninglessness. Back when it was applied to Reagan, what it signified was not just a certain immunity to scandal or controversy, but massive popularity in its own right, enabling him to win two big landslides, and to end office with high approval ratings even after Iran-Contra.

Even then, the effect was somewhat overstated. Reagan’s popularity fluctuated throughout his presidency. Early on, it was pretty low, which contributed to a poor first midterm. He entered office with just 50% approval. The Hinckley attack led to a temporary spike in his popularity, but the economic recession eventually caused it to collapse, which is where it stayed for the next couple of years. It increased in time for reelection amid a strong economic recovery, but in his second term it took a hit following Iran-Contra, even though it recovered later on. This suggests his political success depended to some degree on timing rather than on any intrinsic quality of his. Popular mythology always overstates the importance of personality in defining a president’s political fate, and Reagan is no exception.

When the Teflon concept is applied to Trump, it is even further from making any sense. Imagine a decade ago that I told you there would one day be a president who had consistently mediocre approval ratings, who suffered a brutal midterm, and who was voted out of office at the end of his term–and that this president got the “Teflon” nickname. Your response would probably be, “Huh?”

The rationale is always based on the assumption that no matter how badly Trump performs politically, he’s still doing a lot better than he “should” have. You don’t know how many times I’ve heard the remark, “If any other president did X they’d be finished.” This is usually said without any evidence, since it mostly concerns things that literally no other president has ever done. It also fails to consider how much of Trump’s survival may be a reflection of the broader GOP rather than Trump himself.

@Kari Q: @James Joyner: I’m a California Democrat and I have to admit some disappointment in the governor’s performance with COVID. I just expected better than middle of pack performance from CA’s response to the pandemic considering how smart and skilled a politician Newsom has shown himself to be previously.

Nevertheless I would reference some polling from the KTLA story James links to: “time for someone new” accounted for 58.3% of respondents, while 41.7% said they’d vote to re-elect Newsom. Even if Californians have cooled a bit on Gov. Newsom, that doesn’t mean the “someone new” they’d give their support to would be a CA Republican.

Heh:

As does Texas, and so many others. Excuse me, but doesn’t that mean that in some states at least, partisanship is the defining characteristic of all politics within them?

@Kylopod: I accept that “Teflon” is an odd label to affix to a politician that never broke 46% approval.

But Trump also never fell below 36% approval either, so perhaps we could coin a term for a leader that can sustain that kind of steadfastness from his supporters despite large scale corruption, ineptitude, and general grossness. “Dumb Numb Don” perhaps?

@Scott F.:

So I guess we need to decide when “some disappointment” becomes “wildly unpopular.”

Gray Davis’s handling of the energy crisis was “wildly unpopular.” His approval was in the 20s. Schwarzenegger’s handling of the Great Recession was “wildly unpopular.” His approval rating was in the 20s. With approval ratings in the high 40s to lower 50s, I’d say Newsom is “mildly disappointing” rather than “wildly unpopular.” In fact, at that link you mentioned, a higher percentage of respondents approved his handling of COVID than approved his job overall.

It’s interesting to me that approximately the same percentage of Republicans did not approve the recall (14%) as Democrats who did support it (11%).

@Kari Q:

The longer the RWW (Right Wing Wackos) wait to recall Newsom, the harder it will be. Los Angeles is opening up today – Gyms, indoor dining, yoga studios, bars, and theme parks – with restricted attendance, but it’s opening. The mood in the city is certainly improving. Even if they get the signatures in time, Newsom is going to beat the recall – easily. It won’t be close.

The GOP in California has proven that it can’t govern. Until we purged the GOP from Statewide offices, we coudln’t get anything done. Since then, it’s been budget surpluses and accomplishments – even in the year of an international pandemic.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-08/california-weighs-how-to-spend-surprise-windfall-in-a-pandemic

Meanwhile, apartments and condos are going up everywhere. Housing prices are still skyrocketing. Michael Reynolds bought a house in Silverlake a few years ago, and I’m guessing he’s up 30-40% since then. My little ranch house in the valley and doubled in value, literally, in seven years.

But… California is a shithole and everyone is leaving, right?

I think California/Florida comparisons are ridiculous. I’ve been pretty much everywhere in coastal Cali from San Diego to San Jose—and literally everywhere in Florida since its my home state.

Florida is not set up anything like California. People are spread out and multi-generational households aren’t really a thing here beyond a small group of working poor and farm workers. Covid main attack vector is to get into the house and infect everybody–which is why the Chinese pulled people out of the house. We can’t do that (forcibly) here in America but that’s not a dynamic Florida has baked into its vulnerability profile.

The best apples to apples comparisons amongst the States are going to nursing homes and managed care facilities since they are set up the same pretty much everywhere. If you wanted to broaden out comparisons of States you’d have to control for multi-generational households because States with a larger number of these household configurations have greater vulnerability baked-in regardless of policy.