1968 Wasn’t 1984 (Which Wasn’t 2019)

It's reasonable and just to adjust our outrage based on the context of the time when incidents occurred.

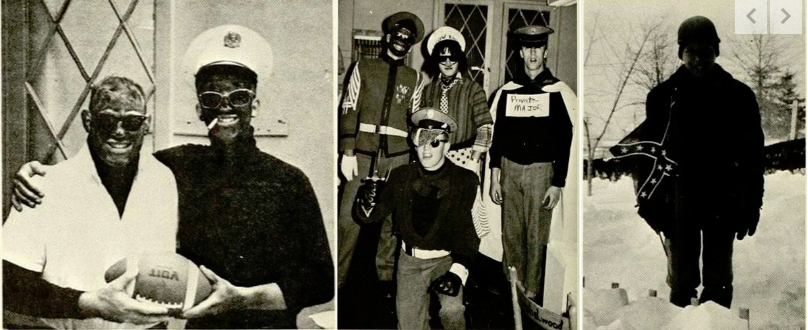

Doug beat me to posting about the news that Tommy Norment, the Republican Senate Majority Leader, was an editor of the 1968 Virginia Military Institute yearbook, which featured many racist quotations and photographs. We essentially agree on the fundamentals: 1968 isn’t 1984.

But an additional bit of context is worth noting: The Class of 1968—the seniors of the yearbook in question—was the last all-white class at VMI. One presumes that there was substantial animus in anticipation of the coming, forced-by-outsiders, integration. There certainly was with the integration of women into the service academies (West Point, Annapolis, and Air Force) in 1976. And when VMI and the Citadel were forced to go co-ed well into the 1990s.

Interestingly, the black graduates from the first class claim to have been treated as equals.

WaPo, Oct 5, 1997 “AT VMI, PIONEERS RECALL BREAKING EARLIER BARRIER”

In February 1968, Harry Gore opened the newspaper and, much to his surprise, read that he would integrate the Virginia Military Institute.

VMI officials had just told the media that they had accepted their first black applicant and that the applications of four other blacks were under consideration for the 1968-69 year.

“There was no name in the newspaper,” Gore recalled. “But I thought: Shucks, I was just accepted by VMI. I’m black. That’s me.’ ”

Without fanfare, lawsuits or federal monitors, VMI became the last public college in the state to integrate when Gore and four other young black men, all Virginians, enrolled on Aug. 22, 1968.

Today, three of those five — Gore, Philip Wilkerson and Richard Valentine — returned for their 25th-year reunion to a school that is again in the midst of change as it assimilates women.

Unlike the 30 women who broke VMI’s gender barrier this fall, the school’s first black cadets had little sense of their pioneering role. Wilkerson and Valentine, like Gore, said they decided to attend VMI before they knew they would be integrating the school. The three also said they believe that the assimilation of women on a campus known for its harsh physical and emotional abuse of freshmen is much more challenging than the adjustment they faced.

Yet they also remembered how their arrival on campus 29 years ago stimulated change for the better. Gradually, their presence — and quiet protests — sparked a debate over the place of Confederate symbolism at VMI and ultimately led to its elimination.

In 1967, then-Superintendent George R.E. Shell announced that VMI would accept black applicants. The U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare had threatened the state with a loss of federal funds if its colleges did not integrate, and one by one through the 1960s, they did.

Frank Easterly, First Class president of VMI’s Class of 1969, held a series of meetings with groups of students to stress that the tough initiation of freshmen, known as the Rat Line, would continue without favor or discrimination — a tiny forerunner of the mass meetings held this year to prepare students and staff for the arrival of women.

“There was a minority, a small minority, who had a strong negative reaction, and they were rather strident and not very tactful in the way they expressed their opinion,” said Easterly, now a Richmond businessman. “But there were no incidents, if that’s the word. It became pretty clear early on that it wasn’t going to be a problem.”

Valentine, who now lives in Jacksonville, Fla., and runs a consulting business, says integration at VMI, for the most part, “turned out to be a non-event.”

“In the Rat Line, everyone was treated {harshly}, and you don’t think it’s racially motivated because the white guy next to you is getting it too,” said Valentine, who grew up in Newport News, Va., and spent most of his career after VMI as an engineer at AT&T Corp.

But beyond the leveling rigors of the Rat Line, VMI was also an institution adorned with troubling symbols for a black cadet, as well for as some of its white students.

At a ceremony held in New Market, Va., each May to commemorate the valor of VMI men in a Civil War battle, the Confederate flag was flown, and cadets were expected to salute it. The regimental band played “Dixie.”

Confederate flags and the playing of “Dixie” also were common at sporting events. And cadets were obliged to salute as they passed Lee Chapel on the campus of neighboring Washington and Lee University, where Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, is buried.

Gore and Valentine balked at those traditions. Gore, who later spent 24 years in the Air Force and retired at the rank of lieutenant colonel, was then a drummer in the regimental band. When it came time to play “Dixie,” he simply stopped drumming — every time.

For all four years they were at VMI, Gore and Valentine refused to salute the Confederate flag. In fact, Valentine, as a First Class lieutenant, remembers giving the order to salute to his company and then not saluting himself. When they could, they took guard duty to avoid ceremonies replete with Confederate symbols. And they always avoided Lee Chapel so they would not have to salute.

“I had never in my life saluted a Confederate flag, and I was never going to,” said Valentine, adding that the school chose to ignore their civil disobedience.

Wilkerson, on the other hand, said he swallowed his resentments for the sake of military cohesion. By his senior year, he was a captain and company commander.

“In a ceremony, if the order was to salute, I saluted,” said Wilkerson, now an Army colonel who is moving to the Washington area from Fort Rucker, Ala., because of a transfer to the Pentagon. “Did I like it? No. But there were more pros than cons at VMI, many more. . . . VMI, in many ways, shaped the person I became.”

After 1968, as increasing numbers of black students enrolled, addressing the issue of Confederate symbols became more and more pressing. A growing number of black cadets tired of the administration’s nod-and-a-wink approach to their protests, and in 1973 they threatened to go AWOL for the New Market ceremony. The entire student body, in response, voted narrowly to eliminate the playing of “Dixie” and the display of the Confederate flag.

The VMI Board of Visitors then voted to change nothing in the ceremony. But the school nonetheless dropped “Dixie” and found ways to make it easier for black cadets to avoid saluting the Confederate flag. In 1974, for instance, the New Market ceremony was held after graduation when only a voluntary corps remained on post.

By the late 1970s, VMI had quietly and completely abandoned the Confederate flag. The New Market ceremony endures, and the tradition of saluting at Lee Chapel continues on a voluntary basis. Of the 460 freshmen who enrolled this fall, 34 were African Americans.

The other two black cadets to integrate VMI in 1968 were Larry Foster, who died in a drowning accident in the summer after his freshman year, and Adam Lawrence Randolph, who dropped out in 1970 and could not be reached last week for comment.

Gore, Wilkerson and Valentine all confess to having had qualms about whether women would disrupt VMI’s core traditions, which had seemed so bound up with the school’s all-male character.

“I wasn’t flat opposed to women going, but VMI has a system that works and nothing about the system changes when black men are introduced,” Valentine said. “VMI can adapt. It’s adapted before. I was just hoping that the arrival of women wouldn’t change the fundamental things, like the Rat Line.”

The three look back on their year in the Rat Line with the glory-days fondness of all its survivors. All three have stayed in touch over the years, although today was only the second time since 1972 that they have been together on post. Wilkerson, who grew up in Hampton, Va., and is the first black VMI graduate to make colonel in the Army, held his promotion ceremony at VMI two years ago to demonstrate his affection for the institute.

“VMI was an incredible bonding experience, and not just for the three of us,” said Gore, also from Hampton, who now lives in O’Fallon, Ill., and works for a defense contractor. “My roommate, Tom Hathaway, became like my second brother, and we’re still very close.”

Granting that the “survivors” of freshmen hazing rituals almost always look back on them with rose-colored glasses, it does look like the VMI leadership took extraordinary measures to ensure black rats were treated fairly. Frankly, much better than West Point did with the integration of women in 1976. Indeed, by my own plebe year eight years later, there was still open animus to women being at the academy.

It’s also interesting that Valentine not only had the remarkable courage to refuse to salute Confederate symbols but that his protests were apparently received with respectful understanding. Indeed, moreso than those of Colin Kaepernick and other African American NFL players almost half a century later.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out that the 1997 story on the reflections of VMI’s first black students coincided with the coming integration of women at the Institute almost exactly half a century later. Not only did those black graduates have, at best, mixed feelings about said integration (as did I at the time*), but the whole kerfuffle seems absurd with the remove of two decades.

Times change. Our social mores have evolved. It’s reasonable and just to adjust our outrage based on the context of the time when incidents occurred. Whatever Norment’s role in the 1968 yearbook, it’s essentially a non-story because of the time. Comparatively, Ralph Northam’s participation in a photo in which one person is in blackface and another in a Klan robe in 1984 is a real issue that had to be addressed. Neither, however, is anything like as big a deal as comments Donald Trump has made about Hispanics and Muslims over the last three years.

_______________

*Unlike 1984 James, 1997 James had long since reconciled himself to the notion that women belonged in the armed forces in leadership roles. Still, I had misgivings as to whether the Constitution required forcing the states of Virginia and South Carolina to gender-integrate VMI and the Citadel.

Interestingly, Citadel admitted blacks in 1966, two years ahead of VMI, and women in 1994, three years ahead of VMI. In both incidences, however, VMI managed the transition much more smoothly. One of the lessons that I learned in hindsight from the gender integration of women at West Point and later into such things as the ranks of fighter pilots is that there needs to be a critical mass, both to create an internal support system and to allow for the possibility of one to fail individually without becoming a symbol of women failing. The Citadel admitted a single woman in 1994, rather hastily in response to a lawsuit. She was woefully unprepared for the physical rigors of the training and failed out within hours of being admitted.

Bigotry never gets old:

James, although I believe that mistakes made in earlier years can and should be expunged by good behavior in later years, I think you are fundamentally wrong about Norment. If anything, in 1968 the issues were more clear and stark than in 1984. Blacks and their white sympathizers were being brutally and sadistically murdered for demanding equality, with the all-but-open approval of the government officials who should have been protecting these heroic people and bringing their torturers and murderers to justice. In 1968 there was absolutely no chance that wearing blackface was the poor choice of a completely unaware doofus. It was absolutely, without question, choosing sides.

So what about the intervening years? Norment has a m supported the outright racist Republican candidate of 2017. And he is a whole hearted supporter of Donald Trump, another out and out racist. In his favor, he came out with a vigorous statement condemning the Nazis in Charlottesville.

As far as has come out, Northam has no track record since 1984 of bigotry. Norment, on the other hand has definitely chosen to support racists for governor and president.

@MarkedMan: Seconded. In 1968, wearing blackface in the midst of a school integration controversy was a clear statement of support for racist policies, whereas in 1984 it could easily have been a juvenile attempt at transgressive humor.

I’m a medical malpractice lawyer. For the last twenty years I’ve represented people who were hurt by the negligence of doctors, nurses, hospitals, and nursing homes. For a decade before that I did medical malpractice defense work, hired by insurance companies to defend the same kinds of claims.

I tell potential clients this as part of the standard talk I give them when we first meet to discuss their case. I say that I think I’m a better lawyer for having lived on the other side, because I understand how that side thinks and what motivates them, but of course I would think that. I tell them that some people want a lawyer who has always been a true believer in their side of the case, and there’s nothing wrong with thinking that way. If that’s the way they feel, I’m not the right lawyer for them and I can give them the names of good lawyers who have never done defense work.

I’ve never had someone end the discussion and tell me they want those other names. People seem to understand that times change and people change, and who you were thirty years ago isn’t necessarily who you are today.

Thirty-five years ago the girl who became my wife warned me about her dad. He had grown up poor in southwest Missouri and had a lot of the racial attitudes that many people who came up the way he did have. She didn’t approve of things he said, but wanted me to understand him instead of just writing him off. I still wouldn’t exactly call him woke, but he voted for Obama twice and we can’t get him to shut up about how great the orthopedic surgeon who rebuilt his shoulder and knees is. Most of the time he doesn’t even mention the fact that the doctor’s black. He tells us he just can’t understand people who judge other people based on color.

People can change. Democrats need a tent that’s big enough to hold people who have changed.

I’m in my mid seventies and obviously was in my mid twenties in 1968. Skirt lengths and necktie widths have moved around, but fundamental principles of justice haven’t. Segregation was evil, but most people have a narrow focus and tolerate a lot of evil in their society. This is true throughout history. Most people did not want to make waves and kept their heads down. Some chose to protest and demonstrate, to cross the Edmunds Pettus bridge. They were heroes bringing light. Some were murderers who wore the robes and hoods of the KKK to oppose the forces of justice. Some supported the outright murderers by donning the garb without more overt actions. This was clear to many of us in the sixties. I thought so then; I thought so in the 1980’s when Reagan chose to start his campaign in Philadelphia, MS, the site of a heinous murder, and I think so now.

It doesn’t seem all that long ago to me.

A columnist at the KC Star has a column recalling the blackface scandal that engulfed the Senate candidacy of Gov. Mel Carnahan in 2000. The writer, though he covered that campaign, didn’t remember the controversy it blew over so quickly. I lived in Missouri at that time and I don’t remember it either.

Times change and what is a transgression today, may not have been 20 years ago or at least it was forgivable. Socially we have reached a point where the behavior of Carnahan and Norment could be put in context of the times and allowed to recede into history, while a similar offence by Northam can’t be excused because times had changed.