A Comparative Note on Amendment Processes

We, as Americans, tend to have a limited knowledge of the institutional variation that exists across democratic systems around the world.

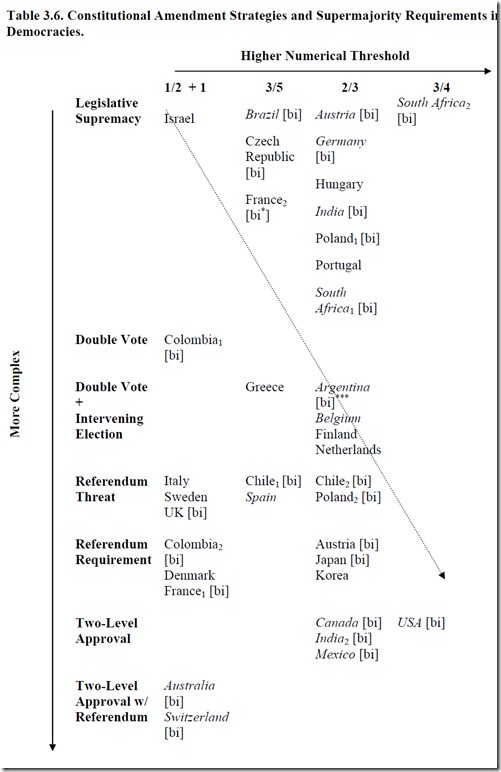

In the comment threads of two previous posts on this general subject (mine and that of Doug Mataconis) there seems to be some confusion as to the institutional options open for amending constitutions. Indeed, several comments seem to indicate an assumption that the options are between majority rule and super-majority rule. However, the reality is more complex than that. There is, in fact, a range in terms of theoretical, as well as practical, options. The table below is from the draft of A Different Democracy: The US in Comparative Perspective by Steven L. Taylor, Matthew S. Shugart, Arend Lijphart, and Bernard Grofman, which compares the US to 29 other democratic states in terms of basic institutional variables. It shows the amendment processes in thirty democratic states (in fact, in some cases it shows two processes, because some constitutions, such as that of India, have different procedures depending on which part of the constitution is being changed or, as in the case of Colombia, simply provides for different options).

One can see that there are multiple variable here, including: 1) role of the legislature, 2) bicameralism, 3) mathematical threshold, 4) number of steps, 5) role of sub-units in federal systems, and 6) the potential for a referendum.

From the text:

Procedures for amending a constitution vary in their numeric thresholds for approval, as well as the institutional complexity of the process. Thus we have two dimensions, where the numeric dimension refers to “how many must agree”, whereas the dimension of complexity refers to “who must agree”.

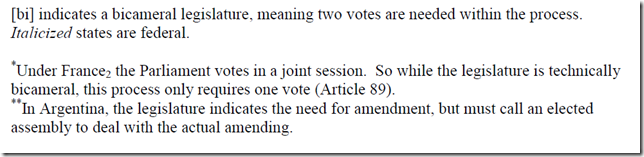

On the numeric dimension, we find that constitutional amendment processes often require some sort of supermajority of the legislature, although not all do. The range of supermajority provisions is from an absolute majority (half plus one ) up to three-quarters. Many constitutions also require a certain number of legislators to be present (a quorum). Numeric thresholds that make approval of amendments more difficult can also be applied to referenda, which are votes by the public–a possibility that brings us to the dimension of complexity.

The second dimension, that of complexity, reflects the number of actors/veto points in the process. In pure legislative supremacy in a unicameral setting, complexity is low, as the number of veto points is one: the legislature itself. However, most amendment processes go beyond just the legislature. Some require multiple votes, forcing legislators to take responsibility twice for voting for change, such as in one of the procedures under the Colombian constitution. Others required two votes, and an intervening election. Instead of one actor, a given legislative body, such a process includes three: the originating legislature, the electorate, and then a newly elected legislature chosen by those voters who will likely have had their vote influenced by their views on constitutional reform. Other systems require a referendum, which directly inserts the voters into the decision-making process, by having them vote for or against the proposed changes. Further, federal systems often include sub-unit legislatures, or have referendum provisions that take account of the states or other units. For example, Switzerland requires a majority of voters nationwide, and also majorities in a majority of sub-units (cantons). The complexity of such procedures is such that the combination of sub-units and super-majority requirement can empower minorities which can band together to block changes to the constitution. We tend to find that federal states have more complex processes for amending their constitutions, which are therefore typically more rigid than their unitary counterparts.

The dotted diagonal line in the table is the line of constitutional rigidity, moving from the least rigid (legislative supremacy with a 50%+1 process) to the most rigid (to a two-level approval process involving a referendum and a 75% threshold for passage). Of course, the most rigid arrangement within the confines of this model is a theoretical one, as none of our democracies have those provisions in place. Only one of our democracies fits in the most flexible category (Israel), with another example of this process existing in New Zealand (a democracy excluded from our study due to the smallness of its population). In the past the UK could also have been included in the least rigid category, but increasingly in the UK a referendum possibility has become the consensus position.

Among our 30 democracies, the United States is the only example of a constitution with a three-fourths supermajority requirement for all amendments. Indeed, it is only one of two cases that uses a three-fourths supermajority at all, as South Africa’s constitution employs it for amending some of the foundational aspects of its constitution. The much more common supermajority, found in most (18 out of 30) of our democracies, is the two-thirds majority—based on the idea that supporters of a constitutional change have to outnumber their opponents by a ratio of at least two to one.

In regards to the UK, there is a recent example: the move to change the electoral system from the single member district plurality system (like we use in the US) to the instant run-off (or alternative vote system) was submitted the population as a referendum (it failed).

The point here, by the way, is not to express a particular preference (although, I have noted that I do think that US system is too restrictive), but rather to provide a broader picture of what exists. Too often discussions about institutional variable in the US context are limited to what the US has and then some imagined single alternative. We, as Americans, tend to have a limited knowledge of the institutional variation that exists across democratic systems around the world.

In practice I’m not sure there’s that much difference between 34 (2/3) and 38 (3/4) of the states; I doubt there are many things that would garner majority support in 34 states but fail to do so in 38 (the ERA notwithstanding, although the ERA has been effectively constitutionalized anyway).

@Chris Lawrence:

I tend to agree. It’s also why I found Levinson’s argument, which I was responding to in my original post to be rather ridiculous. He was clearly pointing to State Constitutions that allow for amendment via legislative action and a simple majority in a referendum, so I must assume that this would be the Amendment process that he would prefer. That is, I think we would all agree, a ridiculous a silly idea that would put far to much power in the hands of eternally shifting majorities.

As for other options, there is, as you said, little effective difference between a 2/3 majority and a 3/4 majority so I don’t see any compelling reason to prefer the first over the second, especially since we’ve been operating quite fine under the second for awhile now.

And, of course, in order change the provisions of Article V you’d have to amend the Constitution as set forth in……….Article V.

@Chris Lawrence: Well, the ERA does show that the higher threshold can matter.

Of course, the real hurdle in our system is the first one: getting 2/3rds of both chambers of Congress to agree (I will ignore the convention option for the sake of discussion). Any measure that can make it through that hoop, especially these days, likely has sufficient public support nationwide that it can pass the 3/4th threshold. And the success rate is quick good: 26 out of 32 that have gone that route. Still, I think it matters insofar as it is easier for a dedicated minority coalition to assemble 25% instead of 34% (not to mention that each additional state means two votes, except in Nebraska).

@Doug Mataconis: Yes, but as a general proposition (and this is rather the point of my post): there are a lot of options beyond simply adopting say, the method used in Alabama and Texas (supermajority vote in legislature and then a referendum). I would agree that that would be a poor model for the nation.

And yes: we are unlikely (to put it mildly) to change this process. Still, for me, I am trying to note that a) we do have, comparatively speaking, a difficult process, and b) there are a lot of options that are worth at least thinking about.

Anyone who wants a constitution that’s easy to amend should take a look at what has happened in Hungary, where only a 2/3 super majority is required (which Fidesz, the ruling party, gained by winning 52.73% of the popular vote.)