A Mostly Good Jobs Report, And A Milestone Finally Passed (Sort Of)

The May Jobs Report was fairly good, and it marks the end of a jobs recession that started six years ago. But things aren't entirely rosy.

Coming after an April report that was among the best that we’ve seen since the Great Recession ended, it was unclear where things would be headed in May, which would give us a good idea of where they’d be headed in the summer and fall as we head toward the 2014 midterm elections. The last revision to Gross Domestic Product growth in the First Quarter of 2014, which actually showed the economy shrinking, certainly raised concerns among investors and economic analysts about what that might mean for the economy going forward. At the same time, underlying numbers for April and early May numbers seemed to indicate that the second three months of the year would be better. On the jobs front, we’ve seen initial unemployment claims shrinking slowly but steadily for the past several weeks as well. In the end, the May numbers, which showed 217,000 jobs created and the U-3 unemployment rate holding steady at 6.3%, was not as good as April, but still fairly decent:

Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 217,000 in May, and the unemployment rate was unchanged at 6.3 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Employment increased in professional and business services, health care and social assistance, food services and drinking places, and transportation and warehousing.

The unemployment rate held at 6.3 percent in May, following a decline of 0.4 percentage point in April. The number of unemployed persons was unchanged in May at 9.8 million. Over the year, the unemployment rate and the number of unemployed persons declined by 1.2 percentage points and 1.9 million, respectively. (See table A-1.)(…)

The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) was essentially unchanged at 3.4 million in May. These individuals accounted for 34.6 percent of the unemployed. Over the past 12 months, the number of long-term unemployed has declined by 979,000. (See table A-12.)

The civilian labor force participation rate was unchanged in May, at 62.8 percent. The participation rate has shown no clear trend since this past October but is down by 0.6 percentage point over the year. The employment-population ratio, at 58.9 percent, was also unchanged in May and has changed little over the year. (See table A-1.)

(…)

Total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 217,000 in May, with gains in professional and business services, health care and social assistance, food services and drinking places, and transportation and warehousing. Over the prior 12 months, nonfarm payroll employment growth had averaged 197,000 per month. (See table B-1.)Professional and business services added 55,000 jobs in May, the same as its average monthly job gain over the prior 12 months. In May, the industry added 7,000 jobs each in computer systems design and related services and in management and technical consulting. Employment in temporary help services continued to trend up (+14,000) and has grown by 224,000 over the past year.

In May, health care and social assistance added 55,000 jobs. The health care industry added 34,000 jobs over the month, twice its average monthly gain for the prior 12 months. Within health care, employment rose in May by 23,000 in ambulatory health care services (which includes offices of physicians, outpatient care centers, and home health care services) and by 7,000 in hospitals. Employment rose by 21,000 in social assistance, compared with an average gain of 7,000 per month over the prior 12 months.

Within leisure and hospitality, employment in food services and drinking places continued to grow, increasing by 32,000 in May and by 311,000 over the past year.

Transportation and warehousing employment rose by 16,000 in May. Over the prior 12 months, the industry had added an average of 9,000 jobs per month. In May, employment growth occurred in support activities for transportation (+6,000) and couriers and messengers (+4,000).

Revisions for the previous two months were minimal. There were no revisions at all to the March numbers, and a small reduction of 6,000 jobs in the April numbers. Over the past three months then, we’ve averaged 234,000 jobs created per month, for the first five months we’ve averaged 213,600 jobs created, and for the last six months the average has been 192,000. The fact that the monthly average is on an upward trajectory is, of course, a very good sign in that it suggests that we’re seeing the trend of job growth increasing, on average, rather than holding steady or decreasing. Assuming the economy continues to grow for the rest of the year, the job situation in the country should continue to improve, although there are still some indications that increased costs associated with the Affordable Care Act will hold employers back from adding new employees in the future unless those costs are outweighed by the revenue that could be generated by adding those new employees.

Nelson Schwartz of The New York Times strikes an optimistic note, and notes that we’ve passed milestone:

American employers added 217,000 workers in May, a bit more than the average monthly gain over the last six months and another sign that the economy may finally be gaining momentum after a weak start to the year.

The unemployment rate was flat at 6.3 percent, the Labor Department said Friday morning in its monthly report on hiring and joblessness.

The labor participation rate, which is closely watched by economists and the Federal Reserve as a yardstick for the overall health of the economy, was unchanged at 62.8 percent.

In recent months, the labor participation rate has been hovering at lows not seen since the late 1970s, a sign that increasing numbers of Americans have given up the search for jobs and dropped out of the work force entirely.

Over the last six months, employers have added an average of just over 200,000 people a month to their payrolls, with momentum rising recently after more anemic job gains in December and January. Average hourly earnings in May rose 5 cents, to $24.38, and are up 2.1 percent over the last 12 months. The length of the typical workweek, 34.5 hours, did not change.

The May figures do represent something of a landmark: Almost exactly five years into the recovery, total payrolls have finally surpassed where they were before the recession.

While the addition of nearly nine million jobs since hiring bottomed out in February 2010 is certainly good news, the number is still far from what is necessary to accommodate new graduates and millions of others who have entered the work force since payrolls last peaked in January 2008 at 138,365,000 jobs.

Private payrolls, which do not include public-sector workers at the federal, state and local levels, surpassed their prerecession level in March.

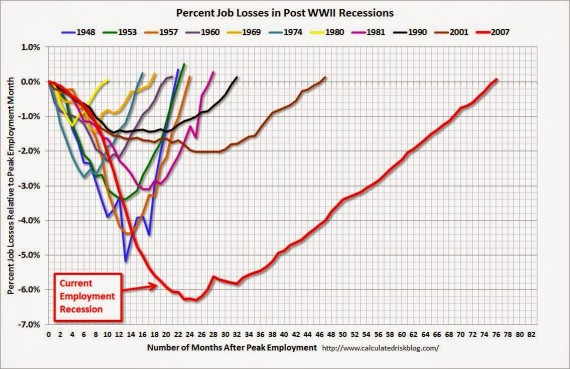

Indeed, it is the case that we’ve finally reached the point where we’re “gotten back” the jobs lost in the Great Recession as the so-called “Scariest Jobs Chart Ever” from Calculated Risk confirms:

So, the longest jobs recession in post-war history is finally over. However, I would’ve exactly start popping champagne corks. The fact that it took some 80 months for us to get back to where we were in 2007 is a measure of both how deep the Great Recession was and how weak the recovery that began in 2009 has actually been. There are still millions of people who have been sitting on the sidelines of the economy for years, and are likely to remain there for some time to come. Additionally, as CNN’s Annalyn Kurtz points out, the milestone doesn’t look as impressive once you factor in population growth:

It took two years to wipe out 8.7 million American jobs but more than four years to gain them all back.

That’s according to the Department of Labor’s latest jobs report, which shows the U.S. economy added 217,000 jobs in May. With that job growth, there are now more jobs in the country than ever before.

The last time we were near this point was January 2008, just before massive layoffs swept throughout the country, leading the unemployment rate to spike to 10%. The unemployment rate is unchanged at 6.3% for May, and much has improved since the worst of the crisis.

Yet, this isn’t the moment to break out the champagne. Given population growth over the last four years, the economy still needs more jobs to truly return to a healthy place. How many more? A whopping 7 million, calculates Heidi Shierholz, an economist with the Economic Policy Institute.

As of May, about 3.4 million Americans had been unemployed for six months or more, and 7.3 million were stuck in part-time jobs although they wanted to work full-time. Both these numbers are still elevated compared to historic norms, and are of concern to Federal Reserve officials, who will meet in two weeks to re-evaluate their stimulus policies.

Overall, this has been the longest jobs recovery since the Department of Labor started tracking jobs data in 1939. Economists surveyed by CNNMoney predict it will take two to three more years to return to “full employment,” which they define as an unemployment rate around 5.5%.

CNBC’s Jeff Cox meanwhile, points out that the jobs that have been created in the last four years aren’t exactly the same as the ones that we lost:

Nonfarm payrolls grew at a pace in line with recent trends, rising 217,000 in May as the unemployment rate held steady at 6.3 percent, according to numbers released Friday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Most of the job gains came on lower-paying industries as wages rose modestly, increasing 5 cents an hour to maintain the modest 2.1 percent growth over the past 12 months. Average hours worked came in flat at 34.5.

A broader measure of joblessness that includes those working part time for economic reasons and those who have quit looking remained elevated at 12.2 percent, though that was a low for the year and the best “U6” measure since October 2008.

Indeed, the internals of the report showed that while actual job growth continues in line with trends, there remains weakness in terms of job quality and other metrics.

Professional and business services along with health led the way in May, with both sectors creating 55,000 new jobs. Hospitality—primarily bars and restaurants—grew by 32,000.

Manufacturing and construction, by contrast, were about flat. Labor force participation, a key metric that whose sharp decline has played a major role in the falling unemployment rate, remained flat at 62.8 percent, matching the worst level since March 1978.

These are encouraging numbers, and it’s good to see the job creation numbers moving upward. Hopefully that will continue. But let’s not fool ourselves here. The labor force participation rate is at the same level it was when Jimmy Carter was President and the original Hawaii Five-O and Barnaby Jones were still on the air. Some of that is, of course, related to baby boomers retiring, but that doesn’t account for all of it. There’s a good segment of the population that has basically given up, and whether they are being supported by welfare, disability, or family, they certainly aren’t leading the productive lives they once were. Additionally, a lot of the jobs that have been created are in lower paying industries than in the past. And a lot of those higher paying jobs simply aren’t going to be coming back thanks either to offshoring, new technology, or increasing worker productivity that means that employers don’t need to hire as many workers as they used to. That’s all worth keeping in mind as we celebrate this milestone that we’ve finally reached.

Still muddling through. Things are less bad. They are still not good. This will continue unless/until policy changes. Policy will not change, at a minimum, until 2016. At a minimum.

@Rob in CT: Things are never again going to be like they were. As a society we have to figure out how to deal with that.

As for us baby boomers, we started leaving the work force over a decade ago. I was an engineer and lost my job to outsourcing in late 2001. Although I was only 56 at the time I like many others in my position didn’t bother looking for another job because I knew there were none.

No, things aren’t great. Where I live, though, they are looking up. In the last month or so I’ve seen five big construction cranes – four downtown and one in an upscale suburban location. It’s been years since the last time I’ve seen one around here, and most construction jobs are good jobs with living wages.

There’s a steel mill starting back up a few miles from my house – they have a big sign outside saying that they need electricians and millwrights, both well-paid trades. Of course, the minimum-wage folks are hiring as well.

Overall, things have improved quite a bit over the last five years.

The good thing is that the Republicans have run out of ways to sabotage the the economy, so now we’ll see a steady recovery . We could make it a better recovery, but the Republicans will block that.

What all this mean is that the economy will be on a (gentle) upswing for the fall, which will help Democrats overall.

Among one thing we see is that Republican predictions that OBAMACARE WILL RUIN THE ECONOMY! has been proven false. In fact, its kind of amazing how quiet the Republicans have gone on the ACA. It’s almost as if it’s working…

@Electroman: Steel mills have been reopening in the US for several years. With the increasing cost of bunker oil it is no longer economical to ship our crushed scrap cars to Asia and then ship it back as steel.

That’s the key to whole shooting match right there.

Public Sector jobs, as the BLS says;

The Socialist President is overseeing a job market that is adding Private Sector jobs hand over fist but not Public Sector jobs…which are down, on net, over 2 million or so.

Forget

I challenge you to show me that simply adding 2 million jobs wouldn’t radically change everything written above.

@Ron Beasley:

Well, sure, in some sense that’s true. Some of how things were was build on fantasy (ever-increase household debt can paper over problems indefinitely, yay!). The only way to get that back is to go back to the destructive fantasy (I fear this is entirely possible, btw), which would be bad.

As for boomers in the workforce, well I don’t know what the overall trend is. My mother is 66 and plans to hang on to her job “until they kick me out.” I hear stories from others about older workers doing the same, either because they feel they need the health benefits (this is a factor for my mother, who likes the back-up to medicare for my – older – father’s medical costs), don’t have enough savings to retire, or some other reason. So some folks are hanging on longer than they’d planned to, and those jobs are *not* going to some young person. I don’t know if it’s a major factor in the high youth unemploynment numbers, but it strikes me as possible.

Anyway, there are things that could be done at the federal level that would be both useful and prudent, but cannot be done because of political opposition. So we muddle through, with things getting better every so slowly.

None of the policy proposals the Dems cannot presently pass would be cure-alls, of course. And of course there are also the GOP proposals that cannot pass which strike me as actively harmful (though there is some reason to believe that if/when the GOP retakes power all the worry about deficits/debt will vanish and we’ll actually see stimulus. Past performance suggests this, but I’m not sure).

Private debt overhang has reduced some, though it’s still pretty godawful (in no small part because even if more jobs are added, most of ’em aren’t good jobs). We continue to run large trade deficits, which I see as a core problem to which neither party seems to have nuch of a policy response. Wealth disparity continues to grow.

Data on household debt levels:

http://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc.html#2014/q1

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/19/business/economy/an-ambiguous-omen-us-household-debt-begins-to-rise-again.html?_r=0

@Rob in CT: I like many of my peers had made good money and led fairly spartan lifestyles so I had a lot of money in the bank. Because of my position in hi-tech I had anticipated the bursting of the tech bubble and converted most of my investments into cash. In addition I owned my condo outright and managed to sell it while it was still a sellers market. I became the live in caregiver for my aging parents – the hardest job I ever had I might add. Most of us never dream that we might someday be cleaning up and bathing our parents. Fortunately my ex mother in law had taught me to cook. All of the companies I worked for are now gone and I have stayed clear of the stock market since 2001.

Doug,

By no standard other than that set over the last six years was this jobs report “decent”.

Solely due to workers giving up on finding employment at all.

This increase is due to credit expansion in a country already heavily over-indebted. Why? Because with a budget deficit scarcely above our current account deficit there is no other source for the financial assets necessary to increase the number and scale of transactions in our economy.

Which means we have made no progress in recovering any of the incomes lost in the wake of a global financial crises resulting from epidemic fraud.

There is no empirical basis whatsoever for the definition of full employment at 5.5%. In reality this means mass unemployment swept under the rug.

The disemployment rate for millenials says otherwise.

This is a junk explanation. Firstly, offshoring is not some law written into the fabric of the cosmos; we actively encourage and promote it to enrich a handful of capitalists by stripping away the country’s productive capacity. It’s policy and there is no logic or benefit in this at all for American society,

Secondly there is absolutely no evidence that technology (which is a euphemism for capital substitution) has played any significant role in net loss of high quality jobs. Technology creates more opportunities for employment, not less as evidenced by a post-WWII productivity rate and employment rate higher than anything experienced since the beginning of the Reagan Revolution and the rise of theo-classical economic dogma. In fact if technology were destroying employment, then China should be experiencing massive job losses, as the industries geared toward producing exports typically employ the latest technology available.

There is no excuse for the failure of this country to provide employment to anyone wishing to work and no way that the wealth we have chosen not to create is a net benefit, nor is it anything but shameful and self-destructive to abandon our young to despair and idleness.

@Ben Wolf:

Simply not true! I spent over 40 years in hi-tech manufacturing. I saw it going from point to point hand wiring to solder wave machines and industrial robots that that placed components. And then along came surface mount. And then came along surface mount technology, industrial robots that can place over 10,000 parts an hour and many of which are so small or the pitch of the IC’s is so small it would be impossible to hand solder them. The motherboard in the computer you used to make your post could not have been assembled by a human being.

@Electroman:

This reminds me of a weird phenomenon I’ve noticed lately that seems to be happening often enough that I think it must be some new trend: businesses that close for a few months, knock down their building, and then build a nearly identical building on the same spot.

Has anyone else noticed this? A lot of the buildings involved are only 5-10 years old anyways. Has it just come to the point that (due to pre-fabrication) it’s cheaper to build a cheap building that only lasts 5-10 years over and over than it is to build an expensive one that will last for decades?

@Ben Wolf:

I buy everything but this:

The question is not just whether technology caused the initial loss of a job, but whether technology renders unnecessary some potential new job. Maybe you got fired from flipping burgers because burger sales were down. Now burger sales are up, but if they have a robot burger-maker, you aren’t getting your job back. Technology has killed jobs that might otherwise have re-absorbed some of the unemployed.

The China is having its own economic problems and we have no reliable way of knowing what their employment picture is. But, no, they aren’t using the latest technology, they’re using manual labor because their manual labor is cheap. It’s not robots assembling iPhones, its people, lots of low-pay people. Those are hands-on, manual labor jobs that we can’t do because Americans can’t live on $2 an hour.

I think comparing the US 2014 to the US post WW2 is completely off the mark. Germany is not in ruins, Japan is not in ruins, the Chinese are not off the grid, we aren’t sitting on huge factories and a massive work force paid for by war bonds and by stripping the British Empire of all its assets. Work could not be easily off-shored in the post-war era. The world today bears no relationship to the world of the 50’s and 60’s. And for the last 20 years we’ve kept alive an illusion of wealth from inflating various bubbles and borrowing more than we can afford.

I would also suggest that there is a conflict inherent in saying 1) Too much off-shoring and 2) Technology isn’t the problem. Technology = offshoring. You can’t manage a massive chain of production encompassing China, India, Germany, South Korea and Silicon Valley without the internet, and that is technology. If a radiologist in India is reading an MRI from Cleveland, that’s technology killing an American job.

Rats, he beat me to it.

The article lists the sectors that added the most jobs, but it didn’t show me what I most wanted to see — namely, who are the losers? Which sectors did not add jobs, or continued to shrink?

I’ll note that the listed sectors with the most gains are almost all areas that require significant specialized training. Burger-flipping and waitressing are the main exceptions, and those hardly represent serious career options for the unemployed looking to change sectors.

Come, let us focus on important things – who is the richest billionaire of them all and what celebrity babes posted sexy selfies today?

The problem with blaming technology, which is just a word for rising productivity, is that it requires that something about the lower increase in productivity over the last thirty-five years be different from previous decades in which productivity rose at a faster pace and yet maintained full employment. We’ve been creating labor-saving machines for several-hundred years and yet employment has expanded with population.

Furthermore I would ask how Japan and Europe in ruins contributed to the post-war economic boom in the United States. Our trade deficits over that period were typically at or below one percent so we weren’t exporting our way into prosperity, we were consuming almost everything our own economy could produce because we took responsibility as a society for maintaining full employment.

I ask again: how does lower productivity growth now result in fewer jobs when higher productivity growth, in a world where we bought all the stuff we could make, happened along with full employment? And by full employment I mean typically around 3-4%, far lower than the ridiculous 5.5% “economists” are vomiting up.

Perhaps it has something to do with a president who declared in 2009 that he was an admirer of Reagan and a fan of Reaganomics?

@Ben Wolf:

The fact that a situation has existed previously for a rather limited period of time does not compel belief that it will continue indefinitely. For 90% of recorded human history pretty much everyone farmed, now very few farm. For 90% of human history man was essentially a beast of burden. Now man sits in cubicles.

If you think about it, it’s only natural that technology – created for the express purpose of doing things humans used to do with their hands and minds – would eventually take a toll on the employment of humans. It’s kind of the point. Technology totally did away with grooms, for example. No horse and carriage, no groom, a job killed by the automobile. In fact it would be shocking if technology didn’t replace some percentage of human workers. And assuming that new human-dependent jobs would always arise is a statement of faith.

@Ben Wolf:

As for the post WW2 world, we had effectively no competition anywhere. No one had money, except us. No one had factories, except us. No one was building ships or making machine tools except us. In addition, we had the only intact labor force in the developed world. WW2 was very, very good to us.

Those conditions are not really similar to our current situation where everyone has capital, everyone has a functioning labor force, everyone can potentially build cars, launch ships, build planes, make machine tools, etc… We had a near-monopoly on just about everything coming out of WW2, plus a big lead in technology. At the same time Russia, China and Eastern Europe were out of the system, off playing at communism.

Given this huge advantage it’s not surprising that we were able to sell lots of stuff and loan lots of money and make a lot of investments, all of which gave us a running start into the 50’s and 60’s.

Just look at cars. It’s fun making cars when no one else has any and no one else is making any. Come the 70’s and the Japanese and Germans were up and running, and they promptly started kicking our asses. We still haven’t recovered and car-making jobs ended up overseas.

Why did national unemployment not permanently increase after introduction of the automobile? Why did demand for cotton workers increase sfter the cotton gin made separating cotton fibers far easier and fsster? By your argument these things were impossible, because technology only destroys jobs.

The U.S. did not export enough to provide full emplyment and rising wages. Period.

Yes, and so we bought everything we produced ourselves. Whether another country had factories had no bearing whatsoever on our real wealth and living standards. Furthermore, if the world was broke then how could the U.S. have gotten rich by selling them things?

While the U.S. auto industry was certainly having some difficulties due to the stupidity of American executives, what crippled it was not some sort of foreign magic but skyrocketing interest rates set by the Federal Reserve. This caused the dollar to appreciate rapidly and made American exports uncompetitive in terms of exchange rates. That is why Detroit went to the government for a bailout, because government policy was responsible as it is responsible for current high unemployment.

@Ben Wolf:

“Perhaps it has something to do with a president who declared in 2009 that he was an admirer of Reagan and a fan of Reaganomics?”

I can’t argue with your economic points, but this is simply a bold-faced lie. Obama expressed admiration for Reagan’s political skills, and his ability to forge a governing coalition, not for Reagonomics.