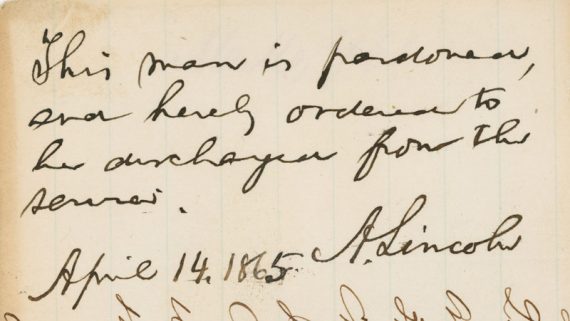

Abraham Lincoln ‘Last’ Official Document Forged

Thomas Lowry fraudulently altered the date of an 1864 pardon from Abraham Lincoln to make it look like it was written on the date of his 1864 assassination.

A fascinating announcement from the National Archives:

Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero announced today that Thomas Lowry, a long-time Lincoln researcher from Woodbridge, VA, confessed on January 12, 2011, to altering an Abraham Lincoln Presidential pardon that is part of the permanent records of the U.S. National Archives. The pardon was for Patrick Murphy, a Civil War soldier in the Union Army who was court-martialed for desertion.

Lowry admitted to changing the date of Murphy’s pardon, written in Lincoln’s hand, from April 14, 1864, to April 14, 1865, the day John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC. Having changed the year from 1864 to 1865, Lowry was then able to claim that this pardon was of significant historical relevance because it could be considered one of, if not the final official act by President Lincoln before his assassination.

[…]

In 1998, Lowry was recognized in the national media for his “discovery” of the Murphy pardon, which was placed on exhibit in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in the National Archives Building in Washington, DC. Lowry subsequently cited the altered record in his book, Don’t Shoot That Boy: Abraham Lincoln and Military Justice, published in 1999.

In making the announcement, the Archivist said, “I am very grateful to Archives staff member Trevor Plante and the Office of the Inspector General for their hard work in uncovering this criminal intention to rewrite history. The Inspector General’s Archival Recovery Team has proven once again its importance in contributing to our shared commitment to secure the nation’s historical record.”

National Archives archivist Trevor Plante reported to the National Archives Office of Inspector General that he believed the date on the Murphy pardon had been altered: the “5” looked like a darker shade of ink than the rest of the date and it appeared that there might have been another number under the “5”. Investigative Archivist Mitchell Yockelson of the Inspector General’s Archival Recovery Team (ART) confirmed Plante’s suspicions.

[…]

In the course of the interview, Lowry admitted to altering the Murphy pardon to reflect the date of Lincoln’s assassination in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2071. Against National Archives regulations, Lowry brought a fountain pen into a National Archives research room where, using fadeproof, pigment-based ink, he altered the date of the Murphy pardon in order to change its historical significance.

This matter was referred to the Department of Justice for criminal prosecution; however the Department of Justice informed the National Archives that the statute of limitations had expired, and therefore Lowry could not be prosecuted. The National Archives, however, has permanently banned him from all of its facilities and research rooms.

I’m not sure which is more amazing: that Lowry would go through so much trouble for such a minuscule amount of fame or that we’ve spent so much time and taxapayer money to correct the record. For that matter, even to my untrained eye, the forgery seems obvious. Why wasn’t it noticed years ago, when Lowry’s “discovery” was being vetted? Presumably, the difference in ink color was at least as obvious then as now?

From the excerpt you provided:

It sounds like the color probably matched at the time, but while the original ink continued to fade, the addition did not, thus leaving the difference in color that exists now.

Michael: That makes sense in the abstract but, geez, it’s only been 12 years. If the ink on Lincoln’s documents is fading that fast, they’re be unreadable within my lifetime. Don’t archives take precautions to ensure that sort of thing doesn’t happen?

As far as I know they do, but I’d imagine some documents (the Gettysburg address, for example) get higher/more expensive levels of preservation than this. This is probably just kept climate controlled and acid-free, but not in inert gases or anything like that..

Having seen some of Lincoln’s original writings, it wouldn’t appear that odd to me without looking for it. He sometimes pressed down on some letters, I suspect it might have to do with the lmitations of his “ink pen”

You asked why it wasn’t noticed until now. First of all, what makes you think that the discovery was properly vetted, as you say? Second, I’m also not convinced it’s a forgery. Look at the rest of the pardon. At the top it starts out quite dark. It then gets lighter. Perhaps this is a result of the ink in the pen emptying out. If it was a fountain pen, this would make sense. It would not surprise me, in fact, if President Lincoln re-dipped his pen before writing the ‘5’ in question, as his signature seems to be about as dark as that ‘5’. It could also explain the appearance of some excess ink on the page around the ‘5’ (currently assumed to be a concealed ‘4’).

You mean this didn’t convince you?

It would have convinced me if he had not recanted his confession.