Linda Brown, Plaintiff In Brown v. Board of Education, Dies At 75

A woman who was at the center of one of the most important Supreme Court cases in American history has died at the age of 75.

Linda Brown, who as a child was the lead named Plaintiff in what became one of the most important, historic, and groundbreaking Supreme Court decisions in American history, has died at the age of 75:

Linda Brown, whose father objected when she was not allowed to attend an all-white school in her neighborhood and who thus came to symbolize one of the most transformative court proceedings in American history, the school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education, died on Sunday in Topeka, Kan. She was 75.

Her death was confirmed on Monday by a spokesman for the Peaceful Rest Funeral Chapel in Topeka, which is handling her funeral arrangements. He did not specify the cause.

It is Ms. Brown’s father, Oliver, whose name is attached to the famous case, although the suit that ended up in the United States Supreme Court actually represented a number of families in several states. In 1954, in a unanimous decision, the court ruled that segregated schools were inherently unequal. The decision upended decades’ worth of educational practice, in the South and elsewhere, and its ramifications are still being felt.

Linda Brown was born on Feb. 20, 1943, in Topeka to Leola and Oliver Brown, according to the funeral home. (Some sources say she was born in 1942.)

Cheryl Brown Henderson, Linda’s sister and the founding president of the Brown Foundation, an educational organization devoted to the case, recalled her parents and others being recruited to press a test case.

“They were told, ‘Find the nearest white school to your home and take your child or children and a witness, and attempt to enroll in the fall, and then come back and tell us what happened,’ ” she said in a video interview for History NOW.

The neighborhood the family lived in was integrated.

“I played with children that were Spanish-American,” Linda Brown said in a 1985 interview. “I played with children that were white, children that were Indian, and black children in my neighborhood.”

Nor were her parents dissatisfied with the black school she was attending. What upset Oliver Brown was the distance Linda had to travel to get to school — first a walk through a rail yard and across a busy road, then a bus ride.

“When I first started the walk it was very frightening to me,” she said, “and then when wintertime came, it was a very cold walk. I remember that. I remember walking, tears freezing up on my face, because I began to cry.”

In an interview with The Miami Herald in 1987, she remembered the fateful day in September 1950 when her father took her to the Sumner School.

“It was a bright, sunny day and we walked briskly,” she said, “and I remember getting to these great big steps.”

The school told her father no, she could not be enrolled.

“I could tell something was wrong, and he came out and took me by the hand and we walked back home,” she said. “We walked even more briskly, and I could feel the tension being transferred from his hand to mine.”

In its ruling, the Supreme Court threw out the prevailing “separate but equal” doctrine, which had allowed racial segregation in the schools as long as students of all races were afforded equal facilities.

“To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race,” the court said, “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.”

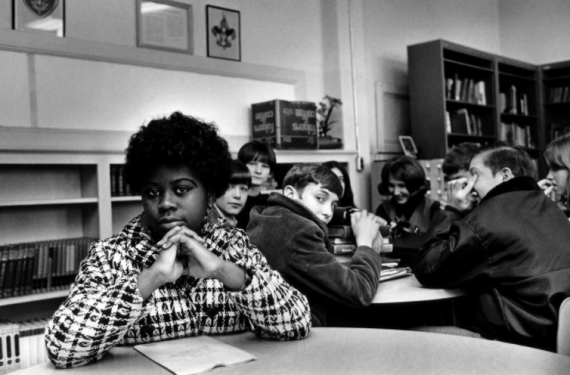

By the time of the ruling, Ms. Brown was in an integrated junior high school. She later became an educational consultant and public speaker.

Her family was among several that reopened the original Brown case in 1979 to argue that the job of integration in Topeka remained incomplete. The case resulted in the opening of several magnet schools.

Ms. Brown was married several times. The funeral home said her survivors include a daughter, Kimberly Smith, although it did not have a complete list of survivors.

Brown’s hometown paper, The Topeka Capital-Journal, had its own obituary:

Friends of Linda Brown recalled a quiet girl thrust into prominence who persevered to become a focal point of the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision ending school segregation.

Brown died Sunday. She was 75, according to the National Archives, though her date of birth has also been reported as 1942. An obituary is expected to be available Tuesday.

Her sister, Cheryl Brown Henderson, founding president of The Brown Foundation, confirmed the death. She said the family wouldn’t comment on her sister’s death. Peaceful Rest Funeral Chapel of Topeka will handle arrangements.

The Brown family long has emphasized the importance many plaintiffs played in Brown v. Board, saying their family has been given an outsized starring role.

Though Linda Brown often stayed out of the spotlight, friends, fellow Topekans and state lawmakers remembered her legacy Monday.

Carolyn Campbell, a lifelong friend of Linda Brown and a former Kansas Board of Education member, recalled to The Capital-Journal riding to Topeka High School together as teenagers.

“Linda was quiet. It was difficult for Linda to be pushed into the spotlight at a young age,” she said.

As she grew older, Linda Brown became more vocal, fighting segregation in schools again in the 1970s and traveling the country to talk about her experience in Topeka.

Carolyn Campbell, a lifelong friend of Linda Brown and a former Kansas Board of Education member, recalled to The Capital-Journal riding to Topeka High School together as teenagers.

“Linda was quiet. It was difficult for Linda to be pushed into the spotlight at a young age,” she said.

As she grew older, Linda Brown became more vocal, fighting segregation in schools again in the 1970s and traveling the country to talk about her experience in Topeka.

Linda Brown was in grade school when she was propelled into the growing civil rights movement.

Her father, Oliver Brown, became the lead plaintiff in the Brown v. Board of Education case after attempting to enroll the third-grader in 1951 in the all-white Sumner Elementary School near the family’s home in Topeka.

He was rebuffed and told his daughter had to attend the all-black Monroe School, about two miles from their home. The Topeka school district maintained 18 elementary schools for white children and four for black children.

Oliver Brown responded by joining a dozen other plaintiffs in the NAACP’s legal challenge of segregated schooling in Kansas. Cases from the District of Columbia and four states — South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware and Kansas — were consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in 1954 that “separate but equal” schools violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

(…)

In 1979, Linda Brown, now with her own children in Topeka schools, became a plaintiff in a resurrected version of Brown, which still had the same title. Topeka Capital-Journal archives indicate the plaintiffs sued the school district for not following through with desegregation.

Federal Judge Richard Rogers sided with the school district in a 1987 decision, but an appeals court reversed his ruling in 1989 and the Supreme Court chose not to review that decision. Rogers then approved a desegregation plan for Topeka Unified School District 501 in 1993.

At a 1989 reception in Topeka, Linda Brown introduced guest speaker Rosa Parks, who’d earned a place in Civil Rights history by being arrested in 1955 after she refused to give up her bus seat to a white person in Montgomery, Ala.

Linda Brown’s name will live eternally, the Rev. Jesse Jackson said at a Topeka church while visiting this community for the 50th anniversary of the Brown v. Board ruling in May 2004.

“God has a way of taking the ordinary people in sub-ordinary positions, exalting them to extraordinary heights and then they become the frame of reference,” he said. “So Topeka is on the map not because of the richest family in Topeka – nobody knows who that is nor does anybody care. Linda Brown’s name, and her father’s name, will live eternally.”

Patrick Woods, who serves on USD 501-s school board, said the Brown family shaped the country and made it a better place. They were ordinary people who decided to stand up for their rights, Woods said, and that’s a lesson for all of us.

“Her impact is so significant,” Woods said, adding that he believes the Brown decision was one of the country’s most monumental court cases.

Topeka activist Sonny Scroggins said he was grateful for Linda Brown.

“When I think about Linda, I think about a figure who was iconic in the evolution of the freedom of Americans of African decent,” he said. “I really appreciate the contributions she made.”

Linda Brown’s experience had a lasting impact on the world, lawmakers and state officials said Monday.

“Sixty-four years ago a young girl from Topeka brought a case that ended segregation in public schools in America,” said Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer.

Colyer said her life reminds us the most unlikely people can have an incredible impact.

Brown v. Board of Education, of course, was the first in what became a long line of cases from the Supreme Court and other levels of the judiciary that not only chipped away at the utterly discredited and legally weak “separate but equal” doctrine established by the Supreme Court’s 1896 ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson but also served in many ways as the impetus for the entire Civil Rights Movement itself which, slowly but surely chipped away at Jim Crow and the final legacy of the Civil War and slavery. What was notable about Brown, of course, is the fact that it originated not in the South or in the “Black Belt” states where discrimination against African-Americans was most virulent and proved to be the hardest to undo, but in a state that had been part of the Union since before the Civil War. In that context, of course, it’s worth noting that, before it became a state, Kansas was the battleground for what ended up being a precursor for the Civil War itself as forces that were for and against the expansion of slavery into what was then known as the Kansas Territory engaged in actual violence over the issue in a time that came to be known as ‘Bleeding Kansas.’ It was also, however, a recognition of the fact that segregation was a reality in areas all across the United States and wasn’t just confined to the former Confederacy. Indeed, one of the hardest and longest fought desegregation battles would come some twenty years after Brown in court and political battles over desegregating public schools erupted in Boston and resulted in rioting by opponents of busing as a solution to segregation and court supervision over the city’s schools that lasted for some fourteen years.

Brown herself, of course, was not the one who prompted the lawsuit that bears her name. As was typical of all of the cases involving children during the desegregation era, the case was brought by her parents and originated at least in part out of the strategy that had been implemented by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which was founded and at the time headed by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, that was meant to use the courts to undermine Jim Crow and other forms of segregation throughout the country. Marshall, of course, was the lead counsel in Brown v. Board of Education and went on to win 29 of the 32 cases he argued before the Supreme Court during his career. Subsequent historical work has shown that the Brown case, along with the companion cases that were part of the overall decision that the Court ultimately issued, was carefully selected by Marshall and his co-counsel, who had spent several years looking for exactly the right type of case to spearhead the legal strategy, supported by studies showing how segregation by race in public schooling was inherently and inevitably unequal, that they had spent so many years developing. In the end, of course, they succeeded perhaps even more than they had been expecting, with a unanimous Supreme Court not only ruling in their favor but also explicitly stating that the “separate but equal” doctrine that Plessy had established was incompatible with the Fourteen Amendment, thus fulfilling the prediction that Justice John Marshall Harlan, the lone dissenter in that case had made 58 years before:

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. It is therefore to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final expositor of the fundamental law of the land, has reached the conclusion that it is competent for a state to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon the basis of race.

In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case.

Harlan was right in 1896, of course, and the decision he dissented from has indeed become one of the most infamous cases in the Supreme Court’s history. Just as Dred Scott was the precursor to the Civil War, Plessy was the precursor to Jim Crow and the oppression that would come with the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in the early 20th Century. The fact that it took a half-century for the Court to overturn that decision is sad and unfortunate but that day did come and it was all because of one brave twelve year old girl and her parents.

Thank you, Linda Brown, for your contributions to justice and equality in our country. Your magnificent efforts deserve emulation as we continue the path toward a better world.

She was history. She’ll live forever.