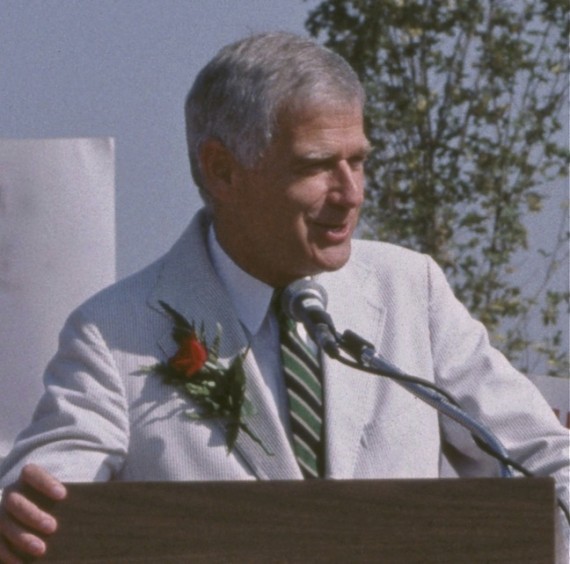

Mark Hatfield Dead at 89

Former Oregon governor and long-time US Senator Mark Hatfield has died.

Former Oregon governor and long-time US Senator Mark Hatfield has died.

Adam Clymer, NYT (“Mark O. Hatfield, Republican Champion of Liberal Causes, Dies at 89“)

Mark O. Hatfield, a liberal Republican who challenged his party’s positions on the Vietnam War and on a balanced-budget amendment to the Constitution during his 30 years as a Senator from Oregon, died on Sunday in Portland, Ore. He was 89.

His death was confirmed by Gerry Frank, a longtime aide.

Mr. Hatfield served in the Senate from 1967 to 1997, spending eight years as chairman of the Appropriations Committee. But he came out against the war even earlier, while serving his second term as governor of Oregon.

At a meeting of the National Governors Association on July 28, 1965, as his colleagues rallied behind President Lyndon B. Johnson, Mr. Hatfield said, “I cannot support the president on what he has done so far.” He complained that Mr. Johnson’s escalation of the war had American troops taking over South Vietnam’s responsibility “to win or lose.” Citing “the deaths of noncombatant men, women and children,” he said the American bombing campaign “merits the general condemnation of mankind.”

At the time, a few prominent Democrats, including Senator Wayne Morse, a fellow Oregonian, were opposing the war. But Mr. Hatfield was the first prominent Republican to come out against it.

By the time he reached the Senate, opposition to the war was growing. In 1970 and 1971, he worked with Senator George S. McGovern of South Dakota on unsuccessful efforts to set a deadline for withdrawing American troops. Mr. Hatfield said at a Washington prayer breakfast in 1973 that it was time for repentance for the “sin that scarred the national soul.” President Richard M. Nixon, who was in attendance, had just signed a cease-fire that ended the combat role for American forces.

Mr. Hatfield was a strong advocate of federal spending on medical research, motivated in part by his father’s suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and cancer among other relatives. For his home state he pushed for appropriations for the Oregon Science and Health University in Portland, and he backed bigger budgets for the National Institutes of Health and the creation of the institutes’ Office for Rare Diseases Research. Medical research, he wrote in 2001, is one of the very few things “the government does extremely well.” In March 1996, he told the Senate that with the end of the cold war, “the Russians are not coming,” alluding to the 1960s film comedy “The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming.” Instead, he said: “The greatest enemy we face today, externally, is the viruses that are coming, the viruses are coming.” Money being spent on defense should be shifted to human needs, he argued.

[…]

Those stands often put him at odds with fellow Republicans. His most serious breach with the party’s senators came in 1995, when he cast the only Republican vote against a constitutional amendment to require a balanced federal budget. His vote meant defeat for the measure, which had 66 votes — one short of the required two-thirds majority. Mr. Hatfield had voted for a balanced-budget amendment in 1982, but changed his mind in 1986 and opposed it. When he cast that decisive vote in 1995, young Republican senators demanded that he be stripped of his Appropriations chairmanship. But senior Republicans blocked that effort.

In 1982, he allied with Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts to campaign for a mutual, United States-Soviet freeze on nuclear weapons. “I see all life as a part of God’s creation,” he told The Christian Science Monitor, “and I think it’s rather audacious and presumptuous of humankind to consider that it has the right to destroy creation, to destroy all life.” But the Senate rejected the freeze in 1983 and again the next year.

Mr. Hatfield’s experience in World War II focused his thinking. A Navy lieutenant, he commanded amphibious landing craft that took Marines ashore — and carried the wounded offshore — at the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. When the war ended, he was sent to Vietnam to ferry Chinese Nationalist troops to fight the Communists. He wrote his parents of observing “squalor” and people begging for food, conditions he blamed not on the Japanese, but on French colonialism. “It has remained my conclusion that the Vietnamese people have been fighting for over 20 years for the cause of nationalism,” he reflected on that experience in a memoir, “Not Quite So Simple,” published in 1968. “They are fighting in the name of social, political and economic justice, and although we may believe their view of ‘justice’ to be false and devilish, it is a vision for which they are prepared to die.” He was next sent to Japan, where, he told Sojourners Magazine in 1996: “One month after the bomb, I walked through the streets of Hiroshima and I saw the utter devastation in every direction from nuclear power.”

As Nick Kristof observes, Hatfield was “the kind of liberal Republican who barely exists today.” In truth, they barely existed even in his own day. Motivated by his deep religious beliefs and the horrors of war, he was for all intents and purposes a pacifist and an advocate for a massive shifting of resources away from military power and toward humanitarian endeavors. Today, he would be on the liberal fringe of the Democratic Party in the Senate.