Politics And Gas Prices: In Chart Form!

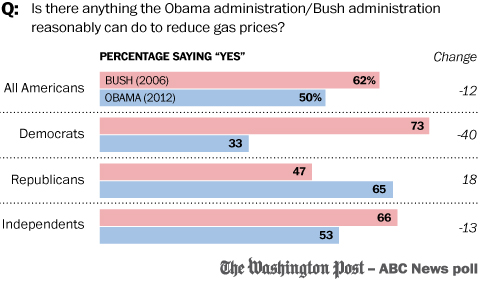

This chart setting forth the results of two different Washington Post/ABC News polls, one from 20o6 and one from 2012, raises some very interesting points:

- In 2006, the vast majority of Democrats believed that the (Republican) Administration could do more to do reduce gas prices. In 2012, only one-third of Democrats believe that there anything more that the (Democratic) Administration can do to reduce gas prices.

- In 2006, a majority of Republicans believed that there wasn’t much more the (Republican) Administration could to to reduce gas prices. In 2012, nearly two-thirds of Republicans say that the (Democratic) Administration could be doing more to reduce gas prices

As for independents and the population as a whole, I would argue that the major reason for the difference between the response six years ago and the response today has to do with the relative popularity of the incumbent. By 2006, George W. Bush’s approval numbers had already started to dip in to the low 30% range1 so it’s not entirely surprising that the public as a whole would have a more negative view of him when it came to a pocket book issue like gas prices.

To me, though, the more striking thing about the chart is two fold. First, there’s how clearly it demonstrates partisan bias. Obviously, Democrats are more likely to blame a Republican President for something that they may not actually have much control over than they are a Democrat, and vice versa for Republicans. From my perspective, that’s yet another argument against viewing the world through partisan blinders. Second, there’s the inherent silliness of polling voters on a question that can really only be answered by economists.Either the President can influence gas prices, or he cannot. What the general public thinks about it is important with regard to that President’s overall approval numbers perhaps, but it doesn’t change the underlying facts. You may as well be polling people on whether they approve of gravity.

1 According to the historical data from Gallup.

I think I would have said “no” both times, but we should note that partisan bias isn’t going to be the only factor. It’s also going to be related to feelings about the middle east, stability, war, etc.

Pair it with a question like “can the President reduce tensions in the middle east,” to extract things like that.

BTW, did you see that economic study which claimed to have extracted the price impact of speculation? That is more than I expected, I think.

@Doug:

Well, it is silly if one is actually looking for an answer to the question of whether presidents do, in fact, affect gas prices. If one is trying to provide empirical evidence for partisan behavior it is actually quite useful.

This is like the soundbite question: if one is simply critiquing people (i.e., they should/should not think X), that’s one thing, but if the goal is seeking to understand why they do what they do (or, in this case, find evidence to support a hypothesis–that opinions are shaped by partisan lenses) then it is helpful.

I wonder, too, if the top number (and the independent one) is because that the public, as a whole, is getting more used to higher gas prices. It is also possible that Bush was expected to have more influence over prices because he was an “oil man.”

@john personna:

This, too.

The middle east probably has something to do with it but the reality is the cost to extract oil is increasing rapidly. We’ve picked all the low hanging fruit. There were some reports out this week about huge reserves of “technically recoverable oil”. The question that I couldn’t find anyone asking is how much of that is economically recoverable?

As for current gasoline prices – the price is near or above $4.00 a gallon because that’s what the rest of the world is willing to pay for it. Even a deep recession or depression wouldn’t lower prices that much because anything below about $3.50 a gallon would not be economically worth the trouble.

There are a few ways you can look at the findings besides through the lens of partisan bias and the president’s overall approval.

The first is that the drop in “yes” responses simply shows that people are learning. The clear consensus among experts is that the most correct answer to the question, especially in the short term, is no. So people who answer yes have the mistaken belief that the president has more leverage here than he really does. And there are all sorts of reasons why people prefer not to think that we’re impotent (think of the Truthers). But a certain percentage can only be fooled once, or twice, and then start to wise up that this is something we don’t have a lot of control over.

About the partisan responses, it’s tempting to blame affiliation biases. But you can also look at it in terms of which levers you’re assuming the president is already using and which you think are effective. A Republican might think that the key to price is supply (drilling), and assume that a Republican president feels the same way and therefore must be doing everything supply-related that can be done; therefore in 2006 there wasn’t anything further the president could do to influence prices, but in 2012 the suspicion might exist that there is. Likewise a Democrat might, stereotypically, look first at demand. Obama would get the benefit of the doubt on encouraging carpooling, electric vehicles, etc, but back in 2006 the suspicion might exist that Bush wasn’t trying hard at all. So you can have an unhypocritical worldview and still answer the question differently in different years.

BTW, nearly every politician and the voters who voted for them since 70s are responsible.

The president has about as much control over gas prices as he does the weather.

Congress and the Federal Reserve, however? Well, those are completely different animals. I won’t kill off too much bandwidth here, but the reality is there are a multitude of measures which, over the long run, all other things being equal, significantly would reduce the relative price of gasoline at the pump: building more refining capacity, lowering or eliminating the federal gas tax and lowering or eliminating federal enviro fees on gas, reigning in loose monetary policies and thereby reversing the trend towards commodity-based inflation. There are others too.