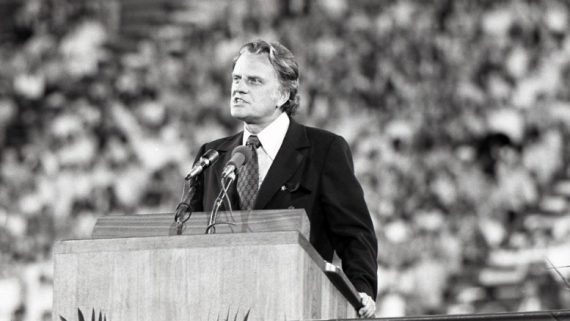

Rev. Billy Graham Dies At 99

Billy Graham was the son of a North Carolina farmer who grew up to become a counselor to Presidents, Prime Ministers, and even a Queen.

Billy Graham, the son of a North Carolina farmer who became a preacher who preached to stadiums full of people and became a confidante to Presidents, Prime Ministers, and even Queen Elizabeth II, has died at the age of 99:

The Rev. Billy Graham, a North Carolina farmer’s son who preached to millions in stadium events he called crusades, becoming a pastor to presidents and the nation’s best-known Christian evangelist for more than 60 years, died on Wednesday at his home. He was 99.

His death was confirmed by Jeremy Blume, a spokesman for the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Mr. Graham had dealt with a number of illnesses in his last years, including prostate cancer, hydrocephalus (a buildup of fluid in the brain) and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

Mr. Graham spread his influence across the country and around the world through a combination of religious conviction, commanding stage presence and shrewd use of radio, television and advanced communication technologies.

A central achievement was his encouraging evangelical Protestants to regain the social influence they had once wielded, reversing a retreat from public life that had begun when their efforts to challenge evolution theory were defeated in the Scopes trial in 1925.

But in his later years, Mr. Graham kept his distance from the evangelical political movement he had helped engender, refusing to endorse candidates and avoiding the volatile issues dear to religious conservatives.

If I get on these other subjects, it divides the audience on an issue that is not the issue I’m promoting,” he said in an interview at his home in North Carolina in 2005 while preparing for his last American crusade, in New York City. “I’m just promoting the Gospel.”

Mr. Graham took the role of evangelist to a new level, lifting it from the sawdust floors of canvas tents in small-town America to the podiums of packed stadiums in the world’s major cities. He wrote some 30 books and was among the first to use new communication technologies for religious purposes. During his “global crusade” from Puerto Rico in 1995, his sermons were translated simultaneously into 48 languages and transmitted to 185 countries by satellite.

Mr. Graham’s standing as a religious leader was unusual: Unlike the pope or the Dalai Lama, he spoke for neither a particular church (though he was a Southern Baptist) nor a particular people.

At times, he seemed to fill the role of national clergyman. He read from Scripture at President Richard M. Nixon’s funeral in California in 1994, offered prayers at a service in the National Cathedral for victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and, despite his failing health, traveled to New Orleans in 2006 to preach to survivors of Hurricane Katrina.

His reach was global, and he was welcomed even by repressive leaders like Kim Il-sung of North Korea, who invited him to preach in Pyongyang’s officially sanctioned churches.

In his younger days, Mr. Graham became a role model for aspiring evangelists, prompting countless young men to copy his cadences, his gestures and even the way he combed his wavy blond hair.

He was not without critics. Early in his career, some mainline Protestant leaders and theologians accused him of preaching a simplistic message of personal salvation that ignored the complexities of societal problems like racism and poverty. Later, critics said he had shown political naïveté in maintaining a close public association with Nixon long after Nixon had been implicated in the cover-up of the Watergate break-in.

Mr. Graham’s image was tainted in 2002 with the release of audiotapes that Nixon had secretly recorded in the White House three decades earlier. The two men were heard agreeing that liberal Jews controlled the media and were responsible for pornography.

“A lot of the Jews are great friends of mine,” Mr. Graham said at one point on the tapes. “They swarm around me and are friendly to me because they know that I’m friendly with Israel. But they don’t know how I really feel about what they are doing to this country.”

Mr. Graham issued a written apology and met with Jewish leaders. In the interview in 2005, he said of the conversation with Nixon: “I didn’t remember it, I still don’t remember it, but it was there. I guess I was sort of caught up in the conversation somehow.”

Mr. Graham drew his essential message from the mainstream of evangelical Protestant belief. Repent of your sins, he told his listeners, accept Jesus as your Savior and be born again. In a typical exhortation, he declared:

“Are you frustrated, bewildered, dejected, breaking under the strains of life? Then listen for a moment to me: Say yes to the Savior tonight, and in a moment you will know such comfort as you have never known. It comes to you quickly, as swiftly as I snap my fingers, just like that.”

Mr. Graham always closed by asking his listeners to “come forward” and commit to a life of Christian faith. When they did so, his well-oiled organization would match new believers with nearby churches. Many thousands of people say they were first brought to church by a Billy Graham crusade.

At the dedication of the Billy Graham Library in Charlotte, N.C., in June 2007, former President Bill Clinton said of Mr. Graham, “When he prays with you in the Oval Office or upstairs in the White House, you feel like he is praying for you, not the president.”

As a popular evangelist, Mr. Graham was by no means unique in American history. George Whitefield in the mid-18th century, Charles G. Finney and Dwight L. Moody in the 19th century, and Billy Sunday at the turn of the 20th were all capable of drawing vast crowds.

But none of them combined the ambition, the talent for organization and the reach of Mr. Graham, who had the advantages of jet travel and electronic media to convey his message. In 2007, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, with 750 employees, estimated that he had preached the Gospel to more than 215 million people in more than 185 countries and territories since beginning his crusades in Grand Rapids, Mich., in October 1947. He reached hundreds of millions more on television, through video and in film.

“This is not mass evangelism,” Mr. Graham liked to say, “but personal evangelism on a mass scale.”

William Franklin Graham Jr. — Billy Frank to his family and friends as a boy — was born near Charlotte on Nov. 7, 1918, the first of four children of William Franklin Graham and Morrow Coffey Graham. He was descended on both sides from pre-Revolution Scottish settlers, and both his grandfathers were Confederate soldiers.

Though the Grahams were Reformed Presbyterians, and though his father insisted on daily readings of the Bible, Billy Frank was an unenthusiastic Christian. He was more interested in reading history, playing baseball and dreaming of becoming a professional ballplayer. His worldliness, his father thought, was mischievous and devilish.

It was the Rev. Mordecai Ham, an itinerant preacher from Kentucky, who was credited with “saving” Billy Graham, in the autumn of 1934, when Billy was 16. After attending Mr. Ham’s revival sessions on a Charlotte street corner several nights in a row, Billy walked up to Mr. Ham to make a “decision for Christ.”

“I can’t say that I felt anything spectacular,” Mr. Graham recalled years later. “I felt very little emotion. I shed no tears. In fact, when I saw others had tears in their eyes, I felt like a hypocrite, and this disturbed me a little. I’m sure I had a tremendous sense of conviction: The Lord did speak to me about certain things in my life. I’m certain of that, but I can’t remember what they were.”

Returning home with a friend that night, Mr. Graham said, he thought: “Now I’ve gotten saved. Now whatever I do can’t unsave me. Even if I killed somebody, I can’t ever be unsaved now.”

After he graduated high school in 1936, Mr. Graham spent the summer selling Fuller brushes door to door before spending an unhappy semester at Bob Jones College, then an unaccredited, fundamentalist school in Cleveland, Tenn. (It is now Bob Jones University, in Greenville, S.C.) He then went to another unaccredited but less restrictive institution, the Florida Bible Institute (now Trinity College), near Tampa.

It was there, he wrote in his 1997 autobiography, “Just as I Am,” that he felt God calling him to the ministry. The call came, he said, during a late-night walk on a golf course. “I got down on my knees at the edge of one of the greens,” he wrote. “Then I prostrated myself on the dewy turf. ‘O God,’ I sobbed, ‘if you want me to serve you, I will.’ ”

“All the surroundings stayed the same,” he continued. “No sign in the heavens. No voice from above. But in my spirit I knew I had been called to the ministry. And I knew my answer was yes.”

After graduating from the Bible Institute, Mr. Graham went to Wheaton College in Illinois, among the nation’s most respected evangelical colleges. At Wheaton, from which he received a degree in anthropology in 1943, he met Ruth McCue Bell, a fellow student whose father was Dr. L. Nelson Bell, a prominent Presbyterian missionary surgeon who had spent many years in China.

Soon after marrying Mrs. Bell in 1943, Mr. Graham accepted the pulpit of the First Baptist Church in Western Springs, Ill., a Chicago suburb. (It later changed its name to the Village Church.) He imbued his sermons with the brand of interdenominational appeal that was to be his hallmark.

It was also in 1943 that he was invited to take over “Songs in the Night,” a Sunday hour of sermonizing and gospel singing broadcast by a Chicago radio station. The program introduced him to electronic evangelism. Its principal singer, the baritone George Beverly Shea, who died in April, would earn fame as a member of the “Billy Graham team.”

As time went on, Graham gradually evolved from preaching to small groups of people to the stadium-filling “crusades” that he became famous for all over the world. Graham also learned how to use technology to spread his word and his ministry and to attract people to come to the events that he would hold in their area. In time, his crusades would become regular staples on television even in parts of the country and the world where you’d be unlikely to find the kind of Evangelical Christianity that he was associated with. As his fame grew, so did his influence and prestige among world leaders generally and American Presidents in particular. While Graham never endorsed candidates for office, Presidents and candidates for the Presidency often sought him out for meetings and he soon earned the unofficial title of “Minister to Presidents” due to the fact that he frequently met with pretty much every American President from Harry Truman to Barack Obama (I don’t recall him having met with President Trump during his first year in office, but he may have) and he became a private spiritual counselor to many of those Presidents over the years and was even known to play a similar role with other world leaders, including Queen Elizabeth II, with whom he developed a long-lasting friendship that began during a visit to the United Kingdom in the 1960s.

One of the things about Graham that became noticeable as time went on was the difference between him and the way the generations of Evangelical Christain preachers that followed him have become far more political than Graham ever was. Even in the 1980s, the differences between Graham and people such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, who became the most prominent faces of the so-called “religious right” that became such a prominent voice on the right that Robertson would end up running for President and finishing in a surprisingly strong second-place position in the Iowa Caucuses in 1988. There was also an even more apparent difference between Graham and the televangelists that came to fame in the 1980s such as Jimmy Swaggart and Jim Bakker, both of whom ultimately saw their ministries essentially destroyed due to sexual escapades and other scandals. Graham himself largely stepped back from his ministry in the past decade or so, and especially after his health began to falter after his wife passed away, and that movement was largely inherited by his son Franklin Graham, who has proven to be far more political and, to be frank about it, far less Christian, than his father was. As a result, the kind of Evangelical Christianity that Billy Graham preached about appears to have been swallowed up by the political movement that Falwell, Robertson, and those like them helped create and which his son has become a willing participant. In many ways, that was an unfortunate development.

He was a stupid, hateful bigot and the world is now a slightly better place.

This (above) is how I first became aware of the Reverend Billy Graham, in his very public association with Richard Nixon. Now, I believe that Nixon used Graham as a prop and ultimately Graham paid a price for allowing himself to be used as such.

The Christian leaders who have followed – Falwell, Robertson, James Dobson, et al – have embraced partisan politics and have no qualms about being used as political props as along as it serves their larger purpose, which is marshaling Republican political support of a robust White Conservative Christian agenda.

I’m not sure that people like Falwell, Robertson or Dobson ever imagined that they would support a malevolent vindictive narcissist like Trump, but …. expediency, access to power, influence.

@teve tory:

That’s true, but he was also a white guy born in 1918 in the south. That was his world, and he had no desire to change it. However, he actually cared about the souls of common white people, as racist as that is. In his dim way, he cared about real temptation. His Christian descendants are scum who have ended up nihilists and fascists concerned about gay people, taxes, and restoring the glory of segregation.

Honestly, perhaps because his less-talented son long took over the operation, I thought he’d already passed.

Has anyone done the math on this grifter’s lifelong take? There’s no more profitable con in this benighted country than selling Jesus and bigotry as a package.

Graham was an enemy to black Americans, gay Americans, women who insist on equal treatment. He was an enemy to science, to reason, to human progress. He revived the most primitive and vile iteration of modern Christianity and did great and lasting harm to this country’s politics and, I would argue, to Christianity itself in the process. I don’t know whether he was a witting con-man as his son clearly is, or whether he was clueless enough to believe his own con, but either way, as @teve said, the world is a teeny, tiny bit better for this man shuffling off.

Oh and of course thoughts and prayers, thoughts and prayers.

What sticks in my mind about Billy Graham is the realization, when I was a kid, that my father couldn’t stand him.

“died at the age of 99”

While it tempting to say that the good die young, here’s a more balanced take from Eric Loomis of Lawyers Guns & Money.

Graham was typical of religious grifters. He talked long, hard and often about taking the hard road and suffering for one’s faith but in reality never asked anything difficult of his flock. He put a clean, well spoken face to their bigotry and prejudices and assured them they were the good people of the world. And while he did so he raked in the big bucks.

The difference between him and his lunatic son boils down to this: Franklin embraces Trump wholeheartedly and rakes in the bucks. Billy would tut-tut over some of Trumps language and meet with him occasionally to gently chide him to do better, and then rake in the big bucks.

@michael reynolds:

At the time of his death, Graham had a net worth of $25 million, making him the seventh-richest pastor in the U.S.

@CSK:

Twenty-five million? That’s about what Jesus died with, isn’t it?

Twenty-five million? That’s about what Jesus died with, isn’t it?

Well, if his mom saved all the gold, frankincense and myrrh that the three Kings brought him at birth and adjusted for inflation over 30+ years…maybe.

@al-Ameda:

To the extent that this is their goal–and I will agree that it is–I’m greatly relieved at the extent that they are the politically “played” rather than political “players.” They do get lots of lip service, but don’t have much in the win column.

I’ll leave it at that

I noticed he got married and got a radio show in like, 1943, but no mention of military service. Why didn’t he serve in World War Two?

@Bruce Henry:

I read somewhere that he planned to become an army chaplain, but “fell ill,” and didn’t recover until after the war ended.

…but no mention of military service.

I’ll bet he prayed for the troops at every Salvation Show during the war!

@CSK:

I should have noted that Graham “fell ill” in 1943, after he married, and recovered two years later, when the war was over.

@James Joyner: Me too. My first reaction to the news was, “Really, he was still alive.” And ‘less talented” seems to barely touch the surface in describing Franklin Graham.

@CSK:

Heel spurs?

I just checked Wikipedia. It says Graham “originally planned” to become an Army chaplain but soon after applying for a commission, came down with the mumps. When I was a kid, the mumps was still pretty common as a childhood illness and kept both of my older sisters, in turn, out of school for a couple of weeks each. I don’t know if the disease affects adults more seriously or not, or why it would keep a young, otherwise healthy young man 4F for two years.

@gVOR08:

That was my first thought.

@Bruce Henry:

Well, since he sired five kids, it apparently didn’t sterilize him.

I have to withhold my comments, as none are good. I will let others speak on this.

Billy Graham was on the wrong side of history

@Bruce Henry:

While I dislike bigoted religious numbnuts, mumps can be a serious disease and even have life-threatening complications.

@HarvardLaw92: I’ve seen the same line attributed to Moms Mabley. I wonder if there’s any way to find out what the original source is, or if it’s just lost in apocryphal history.

@liberal Capitalist: holy moly that is scorching. Wow.

@liberal Capitalist: Actually, for all I disagree with his policies, this actually helps confirm his status as an actual religious revivalist (as opposed to a grifter). It is perfectly consistent with his theology to think that saving individual souls today is far more important than avoiding the secular tragedies of racism and environmental catastrophe — after all, suffering in this world is temporary, but damnation is forever.

Of course, that’s the same mindset that the Spanish Inquisition rode to fame and fortune, but it is consistent, if not laudable.