2022 is a Midterm Year

In case anyone was wondering (and the GOP's prospects are good).

The Cook Political Report has a good (with some caveats explored below) piece on why the 2022 mid-term elections are likely good news for Republicans: Why 2022 Rhymes With the Previous Four Midterms. The headline is a reference to the alleged Mark Twain bon mot, “History never repeats itself but it rhymes.”

It has been known since the results of the 2020 elections were tallied that the likelihood was that the Democrats would lose control of Congress in the mid-terms. It is a long-standing pattern in American politics. A major reason for this, as we saw in the 2021 Virginia governor’s race, is that the electorate shifts in non-presidential elections in a way that tends to help the party that does not control the White House.

The piece notes four factors:

- One Party in Power

- President Biden’s Low Job Approval Ratings

- Enthusiam Gap

- Independent Voters

In regards to the first time, the trends are pretty clear:

The last president to hold onto both the House and Senate majorities post-midterm was Jimmy Carter in 1978.

[…]

The last three midterm elections which featured one-party control of the White House, House and Senate were 2006, 2010, and 2018. In all three cases, the president’s party lost the House. In 2010, Democrats lost seats but managed to hold the Senate.

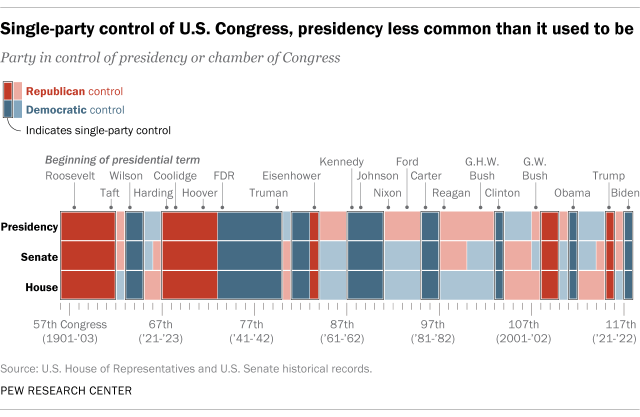

Along these lines, the piece references a Pew study that notes:

Although a single party in charge in Washington is common at the beginning of a new president’s term, there has only been one presidency since 1969 where control has lasted beyond the following midterm election. That was during Democratic President Jimmy Carter’s one term in office, when Democrats retained leadership of the House and Senate in both the 95th and the 96th Congress (1977-1978 and 1979-1980).

Pew provides this useful graphic:

The list is really all linked to the same issue, in my view: once a president is elected, support will wane. An electorate selects a given president for a myriad of reasons. By definition, a given president will fail to deliver on a large number of those reasons. For one thing, voters (irrationally) expect a new president to come into office and change things, well, immediately. This never happens, at least not at a level to make most people happy. So there is a built-in strike one. Then, any president has to rely on Congress to enact major policy changes. Under ideal conditions, this is possible (which would include things like unified caucuses in both chambers and a little thing we like to call a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate), but more likely the tall orders linked to campaign promises combined with a very short window of opportunity makes making people happy unlikely. And, more important than any of that, are conditions largely outside the control of a given president (e.g., things like oil prices, pandemics, and the general state of the economy not to mention global strife). While, yes, policy matters for such things, it matters almost certainly less than people think, and even when it does matter, it sometimes takes years for its effects to come to pass.

To put it more succinctly: even with perfect conditions in Congress and in the world, the actual impact of policy is unlikely to be seen in the first few months of an administration, yet people start deciding if they approve of the president pretty much by late afternoon of Inauguration Day.

This is especially true since presidential approval ratings are essentially a proxy for “how are things going?” and not really an especially great metric of performance (made more complicated by the fact that partisans automatically dislike the president of the opposite party, not to mention that most people really don’t know how governing works).

As such, turn-out and results in a mid-term are driven by a climate that is automatically unfavorable to the sitting president. Further, the out-party is automatically more prone to show up to vote (back to the CPR piece):

there’s a fundamental truth that’s been very consistent over the years: Angry people vote, and complacent or disappointed people don’t.

This, more than anything else, is why the ‘out’ party has an advantage in midterm elections. Their voters are confronted with the consequences of losing the last election every day. That keeps them frustrated, angry and engaged (think, #resistance or #letsgobrandon movements). It’s much harder for the winning side to keep their voters engaged. This is especially true for someone like Biden, whose appeal to many voters wasn’t as much who he was as who he wasn’t.

This point is elaborated on in detail in the piece, to which I refer anyone interested. This is also true of the issue of independents, which is really just a subset of enthusiasm (at least as linked to turnout) and approval ratings.

Let me note that while a negative outcome for the president’s party is not guaranteed, it is nonetheless highly likely. Moreover, I would note that the nature of this pattern points to structural aspects of our political system far more than what a lot of “analysis” is going to say in the coming year (i.e, that it is about messaging or specific policies). There will be a lot of “If only Democrats had done X” or “Why did Democrats say (or not say) Y?” There will be plenty of “Dems in disarray” pieces. And while, sure, message/policy success are factors, they don’t matter as much as other variables such as the partisan makeup of districts.

One major thing the piece misses is the lack of competitive seats to begin with. There is, in my view, an ongoing problem with most discussions of American politics: the assumption that each election starts off with all competitors equally situated at the starting line and then the outcome of the competition is predicated on which party has the best message, the best candidates, and/or “does politics” better. The reality remains that the results in most districts (whether House districts or states as it pertains to the Senate) are largely knowable today. We don’t need to know anything about the quality of candidates or of campaigning to know which party will hold the seat. This needs to be discussed more than it is because the dominant narrative (even from people who would acknowledge this if the issue is raised) is such that it creates the illusion that electoral outcomes are about how well the parties compete, not other factors.

Let me stress: for that to be true (competition being more about policy than structure), we would need a wholly different system that actually allowed voter preferences to translate into seats. That is, we need some form of proportional representation.

Instead, our elections are less about the general preferences of voters and far more about how lines on the map dictate outcomes. This leads to a lot of non-competitive races that simply are not a function of message v. message.

Here’s the Senate forecast at the moment, as summarized by Ballotpedia:

Note out of 34 contests, a maximum of six are truly competitive (and Larry Sabato only has four that as competitive) with another four (at best) that might be non-blowouts. Note, of course, especially as it pertains to the “message” narrative, that only 1/3rd of the Senate is up for re-election at a given moment. This means that the post-election make-up of the Senate cannot be understood to be a function of how well the sitting president nor the current party in power is doing because 2/3rds of the chamber was elected under a different president and a differently constituted congress.

It is not possible to have a complete assessment of House races at this point, as not all the maps are finished, but the Cook Report currently has a grand total of 14 toss-up seats, with another 17 in the “leans” category. (Of course, the fact that the maps are needed for this discussion underscores the problem of single-seat districts: the lines are more important than the voters.

It also cannot be forgotten that the way our elections are scheduled (presidency every four years, but House and 1/3 of the Senate every two) is that we create very different electorates for presidential v. mid-term elections. This fact is simply not fully appreciated/accounted for in these conversations. Presidential elections draw more voters and create a different electorate (partly for reasons noted above) than do mid-terms. Regardless of anything else, this makes the narrative that elections are primarily about competing messaging miss the mark.

Yes, there is some influence of message, policy success, and candidate quality that matter, but not as much as it is made to sound in a typical discussion of American politics. If you ask two different sets of people their opinions, even if there is some commonality between those groups, you will very likely get different answers.

Indeed, it is a strange design to elect a president, and then give them less than two years to perform before deciding to give people a chance to revoke control of the legislature (especially given the electorate churn that I noted). It would make more sense, from a democratic accountability point of view, to structure elections in a way that aligned the interests of the electorate and control of government for a specific term of office. It is noteworthy in the chart above from Pew that the pattern of late has been to give presidents unified government at first but to swiftly then take it away. Given that policy is hard and takes time, that makes little sense if one wants efficacious government (however one might define that).

At a minimum, we need to stop talking like every election is about open competition over sets of ideas. We have to recognize that the outcomes of most races are essentially pre-determined and that only a handful are competitive. We tell ourselves a fictional story that elections are reflections of how well a given party has governed, when, in fact, they don’t tell us that at all–certainly not as as the democratic feedback loop we like to pretend is the case. This is exacerbated by the short amount of time we give presidents and congresses to achieve anything.

Indeed, the lack of significant democratic feedback and, hence, democratic accountability is a major reason why I am a critic of our current institutional configuration.

Yes, it’s bad.

But then there’s this:

All the people referring to Biden as the next Jimmy Carter are actually a little bit reassuring now.

People often put too much emphasis on the number of seats flipped during a midterm cycle, and not on the total number of seats a party has at the end. It’s very unlikely we’ll see the R’s gain 63 seats the way they did in 2010. That’s not because I’m being a rosy optimist. Part of what made the Dems so vulnerable in 2010 is that they held so many reddish districts. Currently there are only 7 districts that voted for Trump but have a Democratic representative. But the R’s don’t need a 63-seat shift to reach the same ends: without getting into the effects of gerrymandering, a pickup of just 29 seats would leave them with the same number of total seats (242) as they had after the 2010 elections. The new redistricting probably puts them even closer toward that goal, requiring even fewer net pickups.

In re COVID and midterms, Darwin may be our only hope.

Let’s go,Darwin!

@Gustopher: There are plenty of examples of presidents being reelected after a bad midterm–Obama, Clinton, Reagan, Eisenhower, Truman, FDR (in 1940). Conversely, presidents who have lost reelection often have suffered relatively small losses–Bush Sr. only lost 8 seats in 1990; Carter 15 in 1978. This has led some people to speculate that a president is actually helped by a bad midterm (in other words, there’s an inverse relationship between a president’s first midterm and the following presidential election). My personal opinion is that there’s no relationship one way or the other. Presidents tend to suffer bad midterms, and they tend to be reelected; that’s all there is to it.

@becca:

As catastrophic as the death toll from Covid has been, it’s still a statistical blip in the overall population. Even if it disproportionately kills off Republican voters at this point, I’m very skeptical it’s enough to make a difference in the upcoming elections.

@Kylopod: My comment is both snark and aspirational. I’m fully aware of the odds against it.

@becca: That’s fine, it’s hard for me to tell because I definitely have seen this point of view expressed in dead earnest (no pun intended). I also am a little annoyed that it seems to reflect a mistaken understanding of Darwinism. (Even now, it still remains the case that most people dying from Covid are older folks who aren’t likely to be having children. They aren’t removing themselves from the gene pool, they’re removing themselves from the planet.)

While it doesn’t change anything in the analysis, the Cook claim that “The last president to hold onto both the House and Senate majorities post-midterm was Jimmy Carter in 1978” is only technically true. Bush gained control of the Senate and increased his lead in the House in 2002. But, of course, that was the first post-9/11 election.

I’d honestly say they’re better than good. Unless something drastically changes, we will have a GOP controlled Senate after November, at a minimum. It’s looking more likely that they retake the House as well IMO.

@HarvardLaw92: I think you’ve got the relative probabilities backwards. It seems almost inevitable they’ll take the House, whereas Dems have at least a fighting chance of keeping the Senate, largely due to a favorable map.

@Kylopod:

Last I checked that’s definitely looking the case. Though the odds for the Dems keeping the Senate, while better than the house, are not great.

Yet, in the case of 2022, it is critically important that we make this election a competition over a set of ideas. Because of the particular set of ideas at play this year – democracy or not – these midterms must not be treated like every other election. This year needs to be treated as the existential battle it will be. If the Republicans take Congress, voter suppression goes federal. The anti-majoritarian inequities of our current institutional configuration will be cemented for our lifetimes.

Our national challenge is to make Trump’s hold on the GOP the central issue of the coming two elections. Engagement should come if people understand our futures rest less on what the Democrats are not than on what the Republicans are.

@Kylopod:

They only have to flip one seat to take control of the Senate. Every Dem toss-up seat is in an R+ electorate, while every Republican toss-up is in a R+ electorate and Dems don’t have Trump to run against in this cycle while Biden’s favorables are in the toilet. I think you’re being overly optimistic.

@HarvardLaw92:

All but one of the toss-up seats listed by Cook are from states Biden won in 2020. The three held by Dems (AZ, GA, and NV) are incumbents seeking reelection. One of the R-held seats is open (PA) and another may yet be (WI, for Johnson has not yet announced whether he’s running again).

What I said was that Dems have a fighting chance of keeping the Senate. If you think that is overly optimistic, you’re implying the Dems don’t have a chance in the world, that the Senate’s gone and they might as well pack their bags. Yet your previous comment seemed to suggest you think the Dems just might have a chance of holding onto the House. All I can say is that this is a wildly unorthodox position; there isn’t a single prominent election analyst who agrees with you. The current consensus holds that the Dems are in trouble and could well lose both houses, but there isn’t a single analyst I’ve run across who thinks the Dems’ chances in the House are better than in the Senate.

@Kylopod:

Actually, I didn’t. I believe the Dems will lose both houses, but the math is easier in the Senate because it only takes a net gain of one seat and the Dems are fighting an uphill battle there. Kelly likely loses to Brnovich. Warnock is a dead man walking – zero chance he gets elected for a full term. Maggie Hasan is a 50/50 shot, likewise Catherine Casto. The GOP will retain NC. PA will likely be Bartos v Fetterman, I think Bartos wins. Wisconsin – who knows? I think you’re putting far too much emphasis on states that Biden won in 2020 without considering his drawing power with Trump off of the table in 2022. As I said, his favorables are in the toilet, and we’re about to have a nice contraction in the capital markets along with rate hikes. It’s not exactly a good hand.

Irrational exuberance and best case scenario annoys me to tears.

@HarvardLaw92:

Way way off. Warnock is going to breeze by Herschel Walker. At least in Georgia, Trump is no more off the table in 2022 than he was on Jan 5, 2021 when Warnock breezed by Kelly Loeffler. Walker is a even disastrous candidate for the Georgia electorate than she was — an inarticulate, wife-beating, carpetbagging Trumper with MPD up against the most gifted Christian orator Georgia politics has seen since MLK.

Just returned from Atlanta for Christmas, and according to local talk radio, chatter, and print news, the Georgia GOP Civil War (over Trump and his minions like loony Marjorie Taylor-Greene and unpopular David Perdue) is, if anything, worse now than it was in Dec-Jan 2021. GA Republicans are divided and depressed, while GA Democrats are unified and energized. The dynamic there is the flip of what we just saw in Virginia.

Candidates still matter, especially in swing states.

@David Kelsey:

I respect your opinion (although I think you might be more than a little biased given your post history), but I continue to disagree.

As I said though, it only takes a net gain of one seat. If it somehow isn’t Georgia, it will be somewhere else.

@James Joyner:

The difference being that Carter started with and retained unified government. Bush started with divided government and then obtain unified government.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Technically, he began with marginal Senate control (50-50 with Cheney as the tie-breaker) and therefore started with unified govt in much the way Dems have now. But then in Apr. 2001, Jim Jeffords left the GOP and began caucusing with the Dems, giving them control of the chamber. In the following midterm the GOP regained the Senate and retained the House.

@Kylopod: 50-50 tie with the veep is “control” of the chamber, but as I often note, the word “control” isn’t quite accurate.

BUT, 50+veep beats 49.

(And actually control of the Senate, i.e., 60 votes, almost never happens).

@David Kelsey:

While I think that Warnock’s incumbency + Walker’s various problems + Abrams’ skill at turnout means that Warnock has a good chance at re-election, I would not count on him breezing to re-election.