Does All-Volunteer Military Break the Social Compact?

Andrew Bacevich bemoans the social impact of the all-volunteer force.

In “Once a duty, military service recast as a right,” Andrew Bacevich bemoans the social impact of the all-volunteer force.

WHAT ARE the duties inherent in citizenship? For Americans, the answer to that question has changed dramatically over time. With regard to military service, the answer prevailing today is this one: No such duty exists. Service in the armed forces, whether pursuant to defending the homeland, advancing the cause of freedom abroad, or expanding the American imperium, has become entirely a matter of individual choice.

In that regard, the recent Pentagon decision to remove restrictions on women serving in combat hardly qualifies as a historic change. Instead, it ratifies a decades-old process that has removed military service from the realm of collective obligation and converted it into an issue of personal preference.

The really big change occurred at the end of the Vietnam War when, heeding President Richard Nixon’s request, Congress abolished the draft. In effect, the state thereby forfeited its authority, exercised in each major US war of the 20th century, to order citizens to take up arms on behalf of country and countrymen. That forfeiture proved irrevocable. Once surrendered, the government’s authority to mandate military service could not be reclaimed. That 18-year-old males still perform the ritual of registering for Selective Service — an action about as weighty as getting a flu shot — does not alter that fact.

So today, to fill the ranks of the armed forces, the state no longer issues orders. Instead, it dangles inducements. In that regard, we should credit the Pentagon with impressive success in its effort to rebrand military service. Once considered an imposition, it now signifies opportunity, offering prospects (depending on rank) of security, status, privilege, or even power.

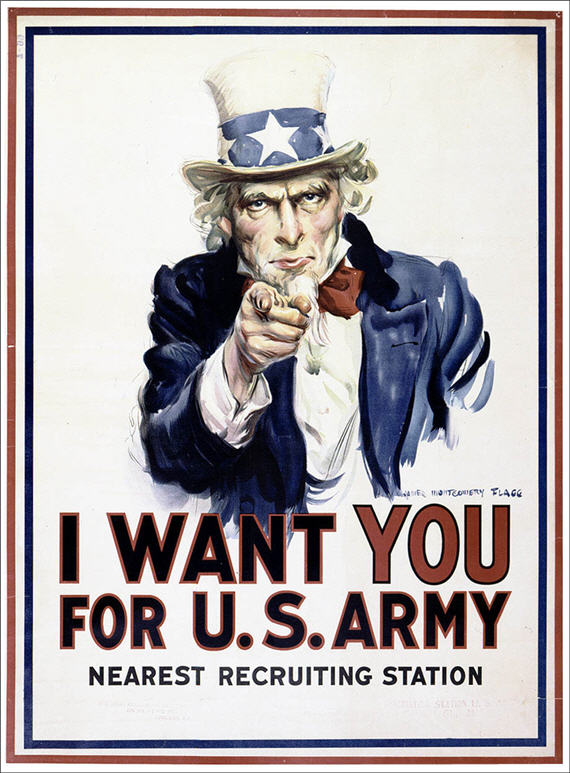

Nothing better captures the shift in emphasis than the iconic US Army recruiting jingle of the 1980s: “Be All That You Can Be.” To an extent that would have astonished the G.I.’s who fought in World War II, Korea, or Vietnam, military service has become a venue for individual self-actualization. In the recruiting sergeant’s office, as elsewhere in American life, the conversation centers not on “us” but on “me.”

[…]

On the surface, the transformation of military service from collective obligation to personal choice meshes nicely with our existing definition of democracy: It demands nothing while excluding no one. What could be fairer?

Yet probe beneath the surface, and the results are anything but democratic. Current arrangements have allowed and even encouraged Americans to disengage from war at a time when war has become all but permanent. Rather than being shared by many, the burden of service and sacrifice is borne by a few, with the voices of those few unlikely to be heard in the corridors of power.

Relieving citizens of any obligation to contribute to the country’s defense has allowed an immense gap to open up between the US military and American society. Here lies one explanation for Washington’s disturbing propensity to instigate unnecessary wars (like Iraq) and to persist in unwinnable ones (like Afghanistan). Some might hope that equipping women soldiers with assault rifles and allowing them to engage in close combat will reverse this trend. Don’t bet on it.

Amidst all the hand-wringing and lamentation for the soul of our society, the only tangible harm Bacevich points to is “Washington’s disturbing propensity to instigate unnecessary wars (like Iraq) and to persist in unwinnable ones (like Afghanistan).” But, of course, the reason that we abandoned the draft to begin with was because we forced millions to serve in and almost 60,000 to die in the unnecessary and unwinnable war in Vietnam. Indeed, with the dispassionate hindsight of history, the vast majority of America’s wars were unnecessary; whether we relied on volunteers or conscripts seems wholly unconnected to our propensity for bad wars. The difference, then, is one of choice: Anyone serving in Iraq or Afghanistan damn well volunteered to be there and was at least able to command a reasonable wage and premium benefits for their sacrifice.

Is it worth mourning that relatively few Americans feel as sense of “duty” to country, at least one that manifests in military service? I suppose. Then again, we have far more people under arms today than we need for any reasonable conception of the national defense under a volunteer system. Why would we want to displace some number of those who wish to be there in favor of those who don’t?

That “the state no longer issues orders” but instead “dangles inducements” strikes me as an unalloyed good. In some circles, we call that “freedom.” And, by almost all accounts, we have a better force because it’s staffed with people who choose to be there rather than are forced to by a coercive state.

Bacevich notes the dearth of accessions from Harvard and at least implies that the current system unfairly burdens the less fortunate. But when hasn’t that been the case? Surely, not during the Vietnam era that immediately preceded the move to an all-volunteer force. We’d decided that those capable or fortunate enough to get into college were too valuable to conscript as cannon fodder. Even during the present wars, when the increased risk of being killed would seem to outweigh the value of the inducements offered, we’re still fielding a force mostly from the middle three quintiles. The sons and daughters of the privileged are indeed mostly eschewing the risk in favor of safer, more prestigious endeavors. The sons and daughters of the poor, meanwhile, have a much harder time qualifying for service, since they’re less likely to be high school graduates and otherwise meet the relatively rigorous enlistment requirements.

It’s probably true that “Current arrangements have allowed and even encouraged Americans to disengage from war at a time when war has become all but permanent.” But, aside from World War II and perhaps the Civil War, when was it otherwise? The Indian Wars were essentially a state of permanent war; arguably, so was the Cold War. Nowadays, through the power of instant mass communications, it’s more possible than ever to follow our war effort. That most don’t isn’t surprising.

Similiarly, that “the burden of service and sacrifice is borne by a few, with the voices of those few unlikely to be heard in the corridors of power” is hardly a new phenomenon. Nor is it obviously a function of a volunteer vice conscript force; after all, we’d likely have the same number of families with sons and daughters in Afghanistan regardless of our staffing procedures. Unless Bacevich is arguing that we’d have vastly more troops there if we could simply order them up? But, surely, he wouldn’t see that as a positive development.

Editor’s note: I’ve appended “and daughters” to “sons” in the first two instances above; it was there originally in the third instance. While we’ve never drafted women and the men are still doing a disproportionate share of the dying, women do constitute some 13 percent of the force.

I think from general principles a democracy should have a military drawn from voters.

But I guess this also ties to our drones and robots future. The grunts will be carbon fiber, the operators will need more training than a 2-year hitch allows.

The choice is between a slave army and a volunteer army. If you don’t want a volunteer army, then you want a slave army.

I share Dr. Bacevich’s concerns about a volunteer army lowering the political costs for military adventurism. Special forces do the same thing. So does the use of drones.

The solution does not lie in the structure of the military but in the predisposition to interventionism. We have persistently elected leaders that supported interventionism. The choice in the last presidential was between two candidates, each of whom supported interventionism.

Until that predisposition and Americans’ support for it changes, changes in the military won’t make a dime’s worth of difference.

@john personna:

Indeed one of the arguments against a drat now, aside from Dave Schuler’s excellent point that it is, at heart, a slave army, is the fact that one simply cannot train-up a bunch of raw draftees in a short period of time like we did during World War II, Korea, and Vietnam

Wasn’t there a volunteer Army of sorts during the Vietnam draft era? If you volunteered for the Regular Army you served 4 years instead of 2 but were much more likely to be stationed stateside or in Europe.

Then there was Bob McNamara’s “Project 100,000”. The idea being you take poor and uneducated draftees, ones who might have been 4-F, and not screen them out so they can develop a sense of duty and responsibility in the military. The problem was they weren’t suited for much other then MOS 11B, infantry, and so most got sent to Vietnam and out into the bush.

@Doug Mataconis:

Gawd. Slavery is a lifelong and hereditary suspension of all civil rights. Let’s compare that to a 2 year hitch, where you still vote, and are only subject to military justice in a specific range of activity.

(You should have just said “Hitler!”)

There is also a certain perniciousness creeping into the all-volunteer services. Veterans are believing that they are more entitled than others who don’t serve. More entitled not just to benefits but to consideration and veneration. It is not a long walk to the belief they should also rule.

Being a twenty year veteran myself who still works in DoD, I see the signs everyday.

I am reminded of Robert Heinlein novel “Starship Troopers” where only veterans are entitled to vote because they are the only ones who know what is like to serve.

All in all this is a valuable discussion and worth bringing up.

@Dave Schuler: Yes, in today’s language anything that imposes an obligation on an individual in service to society is slavery. Laws, regulations, taxes… it is all slavery. Sorry, I don’t buy it.

@Scott:

I think only the movie version of “Starship Troopers” had that the vets were the only ones who can vote. The book said something about even if you blind and deaf the government would find something for you to do during your service term. Even if it was just counting furry caterpillars on bushes.

@john personna: I too think the slavery allusion might be a little overboard, but I am very sympathetic to Dave’s non-interventionist argument.

I have long thought that the military has become too insular. In some ways, it reminds me of a modern day Praetorian Guard. Elite. Influential. Privileged. This worries me.

James has touched on it before, but in modern America (at least the parts I am familiar with) we have a cultural view of the military as “heroes” that cannot do wrong and are above reproach. We tell people that if they haven’t served, they have no right to criticize. “Support our Troops” magnets are on everyone’s cars, but nobody really supports the troops in any meaningful way. There’s little doubt to me that the vast civilian element of society is far detached from an inward looking military that seems almost hereditary and culturally alien from the views of the mainstream.

I’m not sure that bringing back the draft is the way to remedy this. Has the all-volunteer force broke the social compact? No, but it has weakened it perhaps. Modern liberal democracies neither want nor need a conscript army.

At the same time (though the small government guy in me recoils) perhaps we could take a page from some of our allies. Sometimes I wonder if it wouldn’t be healthy for our Republic if young people WERE required to commit to some kind of service. I’m hardly the first or only one to consider the idea. Outside of military service, there are so many opportunities. Think of it as an expanded, better funded Americorps. Even better, a modern CCC or WPA.

@Scott:

Wow, Scott was writing something very much along what I was thinking AS I was writing my response.

@tps: I been many years since I read the book but on the other hand I never saw the movie. I’m sure someone with a better memory than mine will not hesitate to provide corrections.

@tps:

You know, I satisfied a general ed requirement at college with a SciFi course. It was kind of fun because the instructor knew people. For trivia, he said that Starship Troopers was written with a clear intention to support the war in Vietnam, and that The Stainelss Steel rat was another author’s response.

@aFloridian:

I think one answer would be national service for all 18 year olds, with military option. I think we could count on human nature to attract sufficient numbers too that option.

It would be foreign to us, but it would work. As a benefit, everyone gets health care for life, end of that problem.

You could view it as the draft broke the social compact by altering citizen-state relationship. The various drafts over our history produced an sentiment that a citizen could be compelled into government service against their will. Worse still, this attack on individual freedom was an imposition of the majority upon the liberty of the few and select, with almost always the privileged being able to avoid the draft. This was papered over with the sentiment of “civic duty”. But as a few could be compelled, the obligation of all citizens to rise to meet existential crises fell. Thus damaging the original social compact of a citizens duty to be the bulwark against threats that overwhelmed the “hired help”.

That we no longer force, or we could say tax, some citizens to serve in support of the majority’s goals is a good thing. The majority can still, however, proceed with their cause simply by paying more to attract the military force they require. Of course, then you have to tax in some manner to pay those inducements.

@john personna: I doubt that Starship Trooper had much to do with Vietnam since it was written in 1959 but you’re right about the contrast between Heinlein and Harry Harrison. Stainlesss Steel Rat was an early anti-hero going up against the establishment who would find an audience in the late 60s.

@JKB:

Such a market based approach risks turning the armed forces into mercenaries.

@Scott:

Interesting. I wonder if I’m remembering wrong after all these years of if that’s the way my instructor really spun it. I see wikipedia has some interesting stuff on ST and its use(!) in the military.

@JKB:

So this would have started say … 40,000 years ago?

There is something to be said for compulsory service in that all classes of people are forced to go through boot camp together. In our increasingly stratified society, that might be the only time a scion of wealth would ever get to know the son (or daughter – I thoroughly approve of adding women to the draft) of a retail clerk.

That alone might go some way toward amending the ‘makers vs. takers’ and/or ‘lazy rich SOBs vs hard-working blue collar’ myths that plague our political discourse and erode the social compact.

Random thoughts connected to this. I recall the draft was a disaster. Morale was low and widespread throughout the country and military. If women are allowed in combat, there will be a huge outcry when all women in a certain age range find out that they must register with the Selective Service.

I always thought that Bush should have got everyone involved in the war on terrorism effort. Here are some ideas I had to raise money, get everyone helping out, and offset the costs. Sell some kind of bonds. Schools, churches, and other organizations could sponsor a soldier:put out a jar and collect money. Let the public pay and fly on military planes, provided there are seats available. Corporations could pay and put their name on fighter jets and other military planes, also let people pay and write a message on a drone (mine would be “Do you feel lucky, punk?”. Send boxes to soldiers similar to those sent to other countries at Christmas. These could have cds, dvds, books, magazines, puzzles, and pens. Those are some ideas that I had.

Slavery does not have to be lifelong, hereditary nor suspend ALL civil rights. Slavery is a societal and/or governmental system where forced labor and/or involuntary servitude is enforced by the society.

I believe it is indicative that slavery, while unconstitutional in the US. is not banned by name under the laws. Involuntary servitude and forced labor are illegal. As are acts that facilitate slavery, such as trafficking, inducement, etc., since slavery can and does exist in other political/societal domains.

So, in effect, the Draft is the only involuntary servitude/forced labor sanctioned by US society and government and enforced by the society’s laws and, could therefore be considered slavery of a sort. Of course, far more like the historical indentured servant than the slavery abolished during the Civil War.

Well the last active draft was such piece of shat with its deferment policies and special treatment for connected families that it kinda poisoned the well. Personally I have no problem with national service, including but not just limited to the military.

Given the 11+ year grinder we’ve put our military and reservists through, I think it was a mistake not to activate a draft. There are added benefits. Let’s see if the neocons would really favor invading Iran if we dragged their kids into the infantry.

Well, I was thinking about the social compact created when that government, just four score adn seven years later was described as by the People and for the People was created.

But if you have examples from antiquity where people were not subjects but citizens, please offer them. Perhaps Rome?

I think a lot of nonsense has been written by the benefits of a “volunteer military” by well off people who have no intention of volunteering for said military. The reality is that many people sign up for the military because compelled by economic circumstance, not simply because they want to serve “God and country”.

People join because a guy gets a girl pregnant and has to marry her, or because they got a girl pregnant and don’t want to marry her, or because its the only way of out of a dead end job or dead end town, or its the only way to get ANY job, or because some judge somewhere gave them a choice between jail and the ranks. Are they really, truly , volunteering in those cases?

Also too, there is the class question. The WW2 generation saerved together, rich and poor alike. In the case of both the Iraq War and the Afghan War, those who sserved were sent to war by an economic class who didn’t serve, and neither did their children and relatives (They loudly “supported the troops” though). Its not a good thing to have a ruling class and a “dying because I have no better economic prospects” class.

Beyond a year or two of basic military training, perhaps as part of high school to prepare kids to be able to contribute in times of existential crisis in their nation or state, what purpose would national service serve beyond imposing a tax on citizens, collected through labor rather than exchange of money or assets?

Perhaps it could be imposed to pay for all that “free” compulsory schooling they received?

@Scott:

Given the ascendance of “private security companies” and our willingness (at a governmental level) to increasingly utilize them, it’s probably more a case of turning the armed forces into a training program for potential mercenaries with the same paymaster.

Yes, let’s remember that the draft is a historical aberration. Apart from the Civil War, WWI, and the period from WWII through Vietnam, we generally didn’t have a draft in this country. That’s a combined, what, 40 years out of 237? For the vast bulk of our history, the assumption and practice was that most men did not serve in the military.

@Rafer Janders:

In a sense accurate, but it sidesteps the fact that for the majority of our history, we didn’t have a standing army. We had militias, combined with compulsory militia membership and mandated training. (Militia Acts of 1792 ring any bells?) We can’t look at history without recognizing that we also can’t apply the historical environment of 237 years ago to today, at least not without setting aside intellectual consistency.

I think, on some level, that the idea of a universal (and by that I mean truly universal) draft merits consideration – if for no other reason than the fact that it tends to force us to be far more prudent with regards to the use of force. The average American, by and large, can easily get behind bally-hoos for war when he or she is exceedingly unlikely to suffer the consequences of war. That detachment makes it easy to commit to ridiculous excursions undertaken solely for political reasons – which defines the vast bulk of our conflicts post WW2.

There are two major glitches to the service-to-the-state-at-18 idea:

First, this would be an unconscionable burden to many 18-year olds: those who have physical or mental issues, those who are largely the breadwinner to their home; and those who are currently or are in the process of becoming parents.

Second, using these draftees as a CCC, etc. is exactly like the (much more pernicious, imho) drive to use convicts to drop labor costs. All the State would be doing is driving otherwise-employable citizens out of decent jobs (or, more likely, slashing their wages).

@HarvardLaw92:

No, that’s false. We’ve had a standing Army and Navy for most of our history, but they were much smaller than they are today, and the assumption was that they were for defense of the nation (or for smash and grab raids against weaker neighbors such as Mexico), not as occupation forces for a worldwide empire. The modern-day US Army was established in 1791, and the modern US Navy in 1797. Since that time we’ve never been without a standing military.

@Rafer Janders:

For further reference:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Navy#Origins

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Army

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Us_marine_corps#Origins

@Rafer Janders:

You’re missing the point about applying historical context. Yes, we had a standing army – one that could be measured in the thousands – which is to say essentially a non-existent force. In response to any legitimate threat, we had to call up volunteers through the machinations of various state governments. What we consider today to be the concept of a standing army didn’t come about until WW1, and even then only in recognition of the fact that the world – and the nature of warfare – had inexorably changed.

That said, as I noted, my concept of a universal draft makes it arguably more likely that a military thus obtained is less likely to be used for political reasons – precisely because the body politic is far more exposed to the consequences and therefore far less likely to support the rationale.

Throughout history there have been professional armies and there have been conscript armies. (I don’t accept the slave terminology, although there have indeed been slave armies. But that’s a separate thing.)

Generally speaking a professional army allows fewer men under arms do a better job with fewer casualties. Same way that you’ll get better results with a professional police force rather than a sheriff’s posse. So on a pragmatic level the issue is simple.

The idea of spreading the pain of defense is an artifact of an earlier time. It’s nostalgia. First, we have a population of 300 million people. We don’t need a significant proportion of that population to handle defense. So unless we’re proposing to draft people just to draft people, the burden is not going to be spread much more widely than it is now.

Second, warfare is no longer about lining up and firing a musket. It’s a complex, sophisticated business. Training draftees to the level achieved by professional soldiers is impossible. So we’d be drafting people, sending them to die unnecessarily and cause the deaths of professional soldiers in the process who’d find the grunt next to them didn’t know how to operate on the battlefield.

@stonetools:

I have a lot of sympathy for your position, but a lot of people in a lot of jobs suffer because they aren’t rich. You’re more likely to die working as a commercial fisherman than as a soldier. You can often end up crippled by repetitive motion injuries in processing chickens. You’ll get skin cancer picking strawberries in the sun all day. You’ll get black lung digging coal.

None of those things happen to lawyers or accountants or writers. Life is unfair. Not just to soldiers.

@michael reynolds:

The argument isn’t whether we need a significant proportion of our population participating in defense so much as need a much larger proportion of our population exposed to the consequences of war, IMO.

The decision to utilize military force should be a much more painful and considered thing than it currently is in this country. I would agree with Rafer that the proper function of a military is a defensive posture. As it is, we’re using it as a tool for the maintenance of hegemony.

In other words, we’re empire building without calling it an empire.

@HarvardLaw92:

No, I’m applying historical context. The world, and the nature of warfare, didn’t change so much as our conception of our place in the world. We didn’t have a draft because we didn’t need to garrison the entire world, or think of ourselves as a globe-spanning world policeman maintaining bases throughout Europe, Asia and Africa. But there’s nothing inevitable about that, it’s a choice we’ve made, and it’s a choice we can unmake.

@HarvardLaw92:

If we’re empire building we’re doing a piss poor job of it. We did build an empire throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century, during which time — without a professional or standing army of consequence — we rubbed out or displaced Indians, invaded and robbed Mexicans, beat up on defenseless Spaniards, beat up on defenseless Hawaiians, oppressed Filipinos and Cubans and various Central American folks. Most of what we now call the United States we took by force of arms, or bought from people who took it by force of arms.

But since WW2 what have we added? We have bases everywhere, but I think it would be stretching things to say that Japan is part of our empire just because we base troops there. We are the world’s sole superpower, more powerful relative to the rest of the world than any state since the days of imperial Rome. And I am at a loss to find our empire.

@Rafer Janders:

I think you are conflating the world at the outset of WW1 with the world in the aftermath of WW2, no offense intended.

WW1 was the naissance of mechanized, efficient killing on a large scale, and that is the historical context I am speaking of. Some 600,000 died in the Civil War. 16 million died in WW1 – over the same space of time. We went to conscription during WW1 for one simple reason – we couldn’t supply enough bodies via a volunteer process to maintain the fighting.

As for our garrisoning the entire world, I agree, and already did so above. We essentially replaced the Brits, post WW2, as the world’s empire builder. We’ve engaged in warfare since that time for political reasons – as an extension of political policy – and we do so precisely because it is so painless (in a relative sense) for the majority of the population.

“If you don’t want a volunteer army, then you want a slave army.”

False binary choice.

“Liberty is not the power of doing what we like, but the right of being able to do what we ought.”

Lord Acton

We ought to defend our country and serve in its military. A draft is just a lottery to determine who serves. There is nothing wrong with a draft, and it would make wars of adventure a bit less likely, or at least shorten them. The reason to not have a draft is that it makes for a weaker military should we need to fight.

Steve

@michael reynolds:

It’s economic and ideological. One need not install a raj in order to maintain an empire.

@HarvardLaw92:

Actually, I think one must install a Raj or at very least pick the leadership of a country to call it “Empire.” The word has to mean something, and it is not defined as having trade relationships, or treaties of mutual defense. Is the UK part of an American empire? Is France?

Because it would be wrong to let the individuals determine who serves by voluntary choice?

Of course, we could achieve that goal along with having a citizenry ready to serve when needed by having compulsory ROTC in 10th and 11th grades. Now, with our new women in combat policy, for all students in 15 and 16 years old. We could even accommodate those with most disabilities.

We could teach them to shoot, how to maintain an assault rifle by learning on semi-automatic replicas, orienteering, navigation, small unit maneuvers as both member and leader, self discipline, work skills like showing up on time, completing tasks, etc. Even manual arts training. Not to mention physical fitness and unarmed self defense.

Really, it’s the solution to all our problems. I propose right now, that every 15 and 16 yr old spend their summers in camps so that they can prepare to assume their duties as a citizen.

@michael reynolds:

Obvious US adventures in regime change and maintenance aside, I think you are focusing on semantics to avoid the larger point. If it’s easier, just substitute “hegemony” for “empire”. The end result is the same.

@michael reynolds:

I truly dislike the idea of a ruling class, exempt from military service because of wealth , privilege, and political influence, and a ” fighting and dying ” class that the ruling class sends to fight their wars. I note that well off conservatives love the idea of a volunteer military, since that means there is no way they or their kin have to serve in the military they loudly profess admiration for.

I feel that there should be no wars, but if there ARE wars, then everyone from all classes should be at least liable to serve.

@stonetools:

But the net result, setting aside the symbolism, would be that we’d send less-prepared men and women to war. More would die.

I do too, but when has that ever NOT been the case?

How do you figure? Stick to the class argument, stonetools. The one you are making now is pretty bogus, as the armed forces have a reputation of being relatively conservative from the top on down.

@aFloridian:

I’m thinking of Dick Cheney, Newt Gingrich, Mitt Romney, and all the many Republican chickenhawks who loudly pushed and cheerleaded for the Iraq War, after being multiply deferrred out of serving in Vietnam .

All classes served, for the most part, in the Civil War, WW2, the Korean War , and even to a large extent in Vietnam.

@HarvardLaw92:

If what you mean is that we are the world’s only superpower then yes, we are. Hegemon? Perhaps, but is that our fault? An empire is something wrested away from other peoples. We’re alone in our superpower status because other systems and other nations fell by the way side, (USSR, British empire) or aggressively overreached and were crushed. (Germany, Japan.)

We benefited less from imposing our will than by staying out of wars. We waited until the last possible minute to get into WW2, and then only when attacked, and as a result we suffered far less than our allies or opponents. And because our “empire” didn’t extend beyond a few minor holdings we never were trapped in a colonialist economy like the Brits and French.

Basically we are where we are because we made smart political and economic moves while our potential rivals made dumb moves. In any event it owes nothing to our professional military which, thus far has been used in minor wars that will barely earn a mention in history texts 100 years from now.

What strikes me is that we can be pilloried as villains in the 18th and 19th centuries when we stole land and crushed peoples left and right and had no professional military. But we look relatively clean through the 20th when we had a larger, standing army and became a true world power, and the 21st where we have this professional force.

@stonetools: My memories from the 1960’s seems to recall that it was mostly liberal politicians opposed the draft and conservatives seemed to favor it over the volunteer army concept, at least early on.

If there we get into these wars, we should have a plan to win and an exit plan. Occupations seldom succeed; look at the example in our own country of the disastrous “reconstruction” occupation of the southern states by the Federal army.

“No terms except unconditional surrender” General Grant.

@Tyrell:

Historically occupations worked pretty well. In fact there’s not a square foot of earth that wasn’t occupied by some force at the expense of another. But the successful occupations aren’t usually seen as such. For example, the Norman (French, more or less) occupation of England. It’s still in effect. The Normans were never expelled. They melded with the locals and formed anew thing.

The Arab/Muslim occupation of dozens of peoples seems to have held up. As did the American occupation of Indian and Mexican lands. No one’s giving Arizona back to either the Apaches or the Mexicans. (Although . . .)

Or more recently the American and allied occupation of Germany and Japan. Worked pretty well. Both nations are now thoroughly integrated into the western system and neither is a military threat.

So, actually, occupation often works just fine. And other times (US in Philippines, Serbs in Bosnia, Japanese in Manchuria) not so much.

@michael reynolds:

Case in point: Operation Ajax, in which we effectively overthrew the democratically elected government of Iran in order to install the Shah as an autocrat.

We did this in order to ensure the flow of cheap oil on our terms. In the process, we denied to the people of Iran the rightful benefit of their natural resources and subjected them to a police state.

There are many other similar examples. Pinochet. US & British attempts to control energy resources in Southeast Asia at Japan’s expense. Long term US interference in Nicaragua. Our installation of the Ba’ath party into power in Iraq (until it became more of a problem for us than a benefit). etc. etc. etc.

We have a long and storied history of interfering in the affairs of sovereign nations to our benefit, and I’m entirely convinced that the folks in these places would feel that things had been wrested away from them – namely self-determination, natural wealth, etc. I’d argue that we can trace much of the ill-will that exists against the US worldwide directly to this pattern of what can only (IMO) be called empire building.

Come to think of it – I guess it is necessary to install a raj, given how often we’ve felt justified in doing so.

No problem with the All Volunteer force. Nothing sucks ball$ like commanding men and women that dont’ want to be there. I DO believe however, that they should be a draft for 2 years in a national peace corps working on national projects to include community policing in area overrun with crime. Responsibility isn’t natural–you have to instill it in people. The only waivers would be for military service or advanced degrees in critical disciplines.

@michael reynolds:

Interesting question: do you believe that the Marshall Plan was intended to rebuild Europe so that they could compete with us economically (altruism), or you do believe that it was intended to facilitate their purchase of US products and services (self-interest)?

@ Tyrell

Actually, it was mostly the kids who did not want to go and get their asses shot off in Vietnam, and their girlfriends. And there were principled men like Muhammad Ali who refused to go and kill people that he correctly perceived were no threat to us.

@HarvardLaw92:

The answer is yes. Yes, it was altruism, and yes it was self-interest. I have yet to meet my first pure, singular, unambiguous motivation for anything.

@HarvardLaw92:

Yeah, yeah, Pinochet and the Shah and the rest, I know the whole litany. They amount to very little. It was marginalia.

Again, we are THE superpower. We possess 5,000 deliverable nuclear warheads. We have the ONLY world-class military. Yet the only examples you come up with are cold war meddling with third and fourth rate powers. Come on, that’s empire building? Please.

You want some empire building? 1846 we use a pretext to invade Mexico and walked away with half their territory, including NM, AZ, NV, parts of CO and CA. That’s empire building, and we did it when we were a regional power with a negligible army and a joke of a navy. To come anywhere close to that in modern scale we’d have to seize all of South and Central America and make them US states.

@ HarvardLaw92

You are missing a key goal of the Marshall Plan – to rebuild western european economies so that communism would not be an attractive option for their citizens.

@JKB:

In reply to the question by JKB:

Roman history is quite long and not easily summarized. I do know in the “good old days” of the Roman Republic (as Tacitus might consider it), when Rome was seriously threatened the Senate appointed a dictator, who had power to raise an army and use it. The dictatorships were typically for six months, though Sulla’s lasted five years (and was more of a purge than a war). In a word, martial law extended to the whole of society during a real, knock-em-sock-em conflict with a mortal enemy.

Later in Roman history, men were required to serve ten years in the army. The fact that the Romans allowed marriage to only one woman was no doubt crucial to the success of this policy: otherwise the men at arms would be without any means of procreation (the men not at arms would have taken all the women to themselves), and it just would not have worked out.

After Rome attained her greatness, moral laxity ensued. The army was paid with donatives. Eventually there were not enough citizens to fill the ranks, and one of the emperors at Constantinople issued a decree allowing generals to conscript barbarians (= those who do not speak either Latin or Greek) into the ranks.

The generals in the western part of the Empire filled the ranks with barbarians, and the difference in language and treatment was devastating to morale. (The barbarians insisted on and got better treatment than the Latin-speaking soldiers.) The phalanxes no longer fought as a cohesive unit, with disastrous consequences on the field of battle.

The generals in the East, where Greek was spoken, were too much filled with a sense of cultural superiority to allow barbarians into their ranks. (The Greek-speaking part of the empire believed in their own cultural superiority all through Imperial history.) A book I read attributes the fact that the West fell by 476, whereas the East continued as an empire until 1453, to this difference in recruitment methods.

I offer no morals to the story. I’ll leave each to his own interpretation how to apply these slices of history to the present day.

@michael reynolds:

You are missing the forest for the trees. If having 5,000 nuclear warheads makes us the only superpower, and we’re so amazingly awesome as a result, then why the need to expend so much time and effort interfering in the affairs of other nations?

@john personna: “You know, I satisfied a general ed requirement at college with a SciFi course. It was kind of fun because the instructor knew people. For trivia, he said that Starship Troopers was written with a clear intention to support the war in Vietnam, and that The Stainelss Steel rat was another author’s response.”

That would be ‘The Forever War’.

@JKB: Seconding JKB. Slavery *can be* hereditary and/or lifelong, but does not have to be.

@HarvardLaw92:

I don’t think you’ve made a case that we have expended much effort interfering in the affairs of other nations. In comparison to our capacity for doing so, we’re doing very little. In any event, the original question was about “empire” which shifted to “hegemony” and is now down to “interference.”

@ Barry

Joe Haldeman?

@michael reynolds:

That´s part of the problem. Since most Americans do not know any language other than English(Even Americans in the Academia) and since most Americans do not served in the Army most people overestimate the power of the United States and underestimate the cost of interfering with the affairs of other nations.

One could argue that such warmongers as John McCain served in the Military, but waging endless wars while only 1% of the population are fighting them is problematic.

I think it would never even occur to the overwhelming majority of our fighters to consider it a ‘duty,’ ‘sacrifice’ or ‘obligation’ to fight for America. I think they consider it an honor. A free army is the only moral way to defend a free country. I can think of no greater statist violation of individual rights than to order men to their death. And I’m speaking from a family whose every generation has volunteered for service and fought in wars, from Korea and Vietnam to both World Wars. Moreover, it’s the only practical way to win wars. Men pushed to the front lines won’t fight very hard or very long. If we are attacked, and there’s a need for soldiers, then any young man who values his rights and freedom should–and historically has–been honored to volunteer to defend them.

@JKB: We do have a huge prison labor market in this country, but you’d never know it unless you watch MSNBC.

@Oliver Wright:

There is this thing called conscientious objector status. In previous wars it was pretty badly managed. I’d open it to people who did not choose to fight so if drafted you may not fight but you will serve.

I can accept many people who serve voluntarily do consider it an honor. Too bad their service is often used for less than honorable applications. This is probably the main reason why I will not volunteer in the armed forces and the reason they wouldn’t want me. For example, I would not have gone to fight in Iraq. Operating in medical and emergency support I could justify but not armed conflict there.

I remember the draft Army. FTA grafitti everywhere. Not Future Teachers Association. Overflowing stockades. Detachments of MPs to haul in the AWOLs and deserters. More crime and violence generally.

The good thing was there were a lot of very good people brought in who would otherwise have never served. A good deal of the enlisted men in clerical positions in battalion headquarters were college graduates.

All in all I will take the volunteer Army any old time. I served in both and that the way I see it.

I wonder if all the people advocating mandatory service are personally willing to point a gun at an eighteen year old’s head to make them serve, force other people to point those guns, or simply rely on volunteers?