The Power of Partisanship and the Weakness of “Moderation” Arguments

Lee Drutman does the math.

I have been arguing here at OTB for quite some time that the key variable for understanding electoral outcomes in the United States is partisan identity, not messaging or the ideological viewpoint of candidates. While yes, candidate quality is a legitimate variable, it is not as important as most contemporary discussions of politics would indicate. This has become an issue of discussion of late because of the Welcome PAC analysis that I discussed last week.

Lee Drutman, a political scientist and democracy reform advocate, has done the math, and it rather dramatically backs up what I have been arguing. I would highly recommend his post, The moderation debate fiddles with 2% while democracy’s dimensionality collapses.

In a recent post, Stanford political scientist Adam Bonica argued that once you control for money and incumbency, the moderation advantage vanishes. But his broader point resonates with me: “the moderation advantage that once existed has faded… because the electoral landscape has changed.” That’s exactly right.

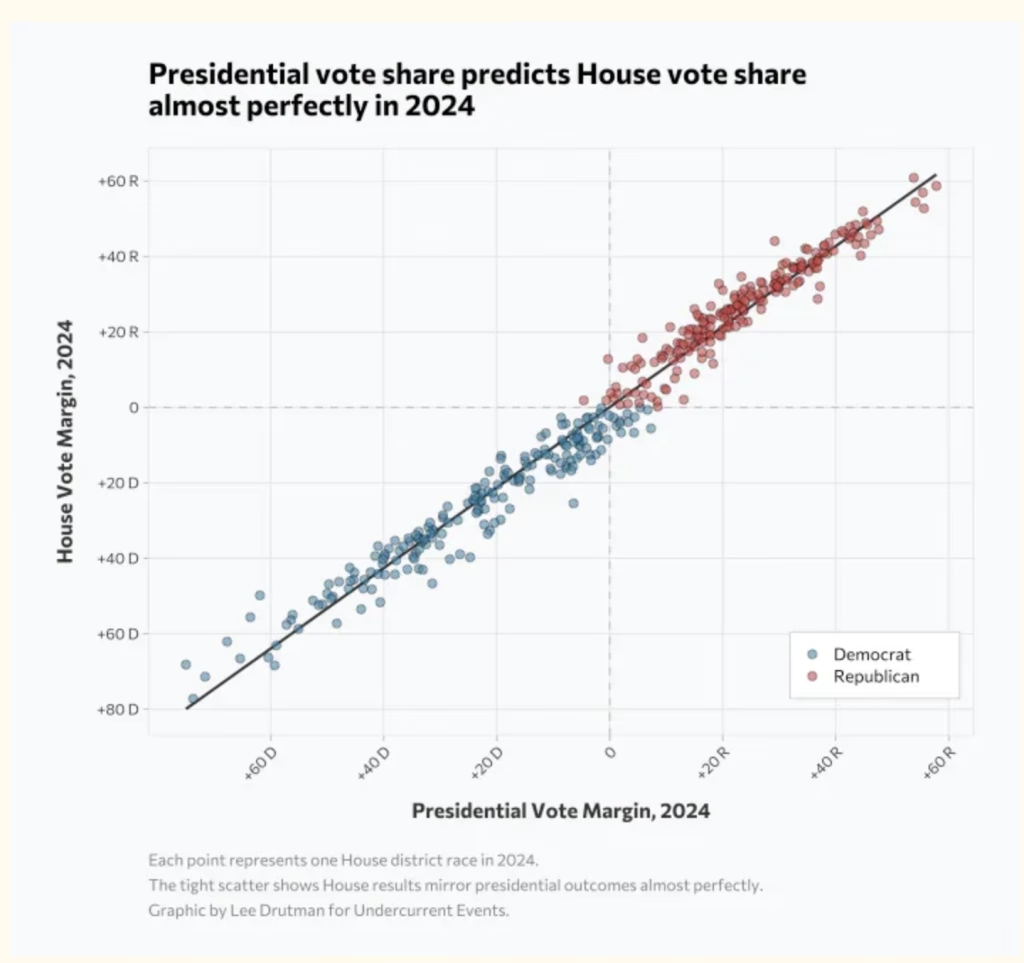

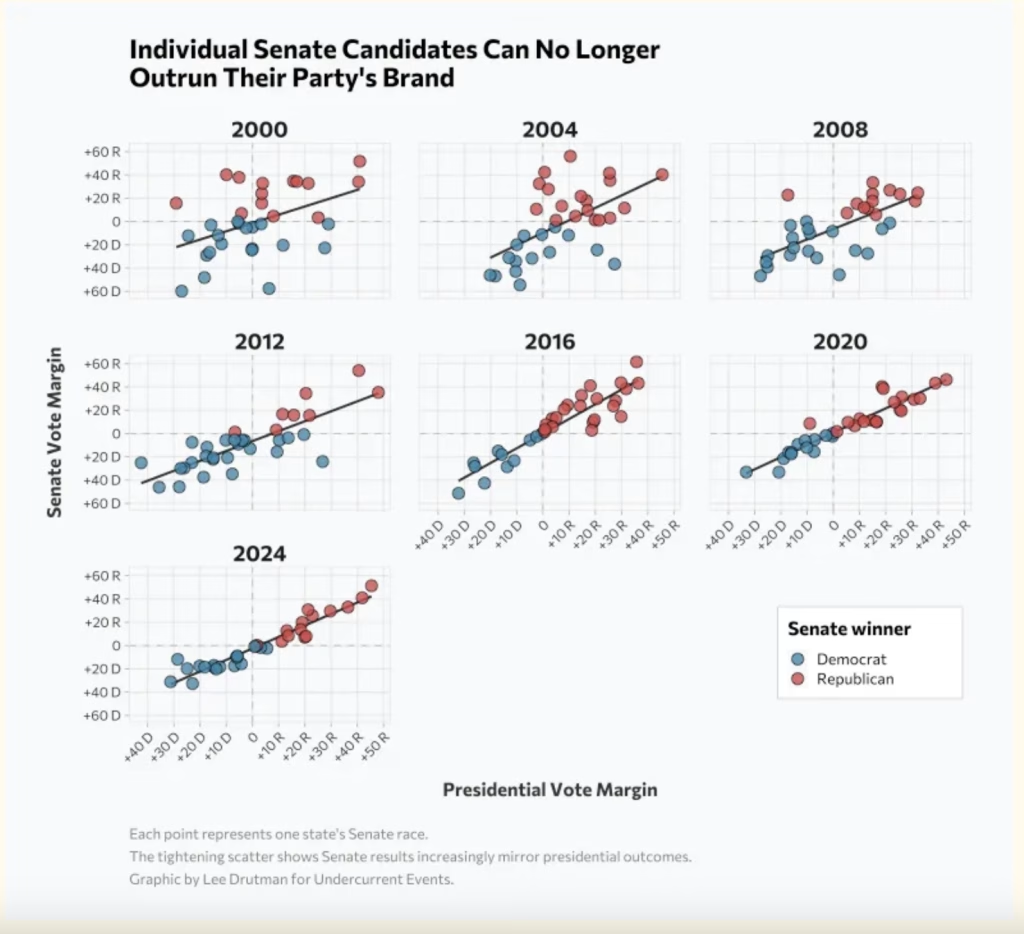

By my analysis (below), presidential vote share now explains 98% of House outcomes. In the Senate, it’s 91%. In 2000, roughly half of Senate races were competitive enough that candidate quality could flip them. By 2024, only 12% were.

[…]

Candidate quality, local factors, ideological nuance, local organizing forces—all those dimensions that used to create competition and accountability have been crushed down to near-irrelevance. In an age of hyper-partisan, hyper-nationalized voting and calcified politics, the big problem is that nothing matters.

This all intersects with my ongoing concerns about the competitiveness and responsiveness (or, in fact, lack thereof) within our politics.

He provides some stunning graphs.

For example:

He explains:

The big story: Presidential vote share determines House vote share with near-perfect precision. Or, more specifically, if you knew how the district voted in the presidential election, you could tell me with 98 percent accuracy how the district voted for the House. Yes, candidate quality matters, on the margins. But those margins are very very very very very tiny in today’s politics.

All those dots? They represent candidates of many different types of quality. And yet, they all hug the same line. Put another way: In today’s electoral environment, almost nothing individual candidates do matters. Only super-candidates can distinguish themselves from their party’s presidential candidate. And only barely.

Check out the evolution of Senate elections over time.

What does this mean?

Today, few voters consider the distinct qualities of the candidate. They are looking at the D or the R next to the candidate. Even the best candidates struggle against the crushing weight of partisan gravity.

[…]

In 2000, an R-squared of 0.20 meant that presidential vote share explained about 20 percent of the variance in Senate vote share across states. The remaining 80 percent of variance was attributable to candidate-specific effects and state-level factors.

Fast forward to 2024: the R-squared reached 0.90, meaning presidential vote share now explained 90 percent of the variance in Senate vote share. Less than 10 percent of the variance remained for the candidate effect or state-specific factors. Fewer states remained legitimately competitive.

Two big inter-related trends explain the collapse: partisan polarization and nationalization of politics. Party sorting means most voters now live in one coalition or the other. Fewer and fewer consider voting for the other side. Just Democratic voters and Republican voters.

This is all pretty damn compelling and illustrates why messaging and moderation strategies don’t impress me much.

I would note that this is also why I argue that the way our parties are run leads to substantial problems for our politics. Since a given president can come in and reshape what it means to be an R or a D without changing who is an R or a D in any mass way, it means we can get situations like Trump. And Drutman talks at length in this post about the authoritarian consequences of what he is observing.

All of this, too, speaks to the general deficiencies of our institutions.

Lee and I agree that the core problem is the party system, and we agree that the long-term solution is proportional representation. Lee makes an argument in the piece on fusion voting, which I do not oppose but am skeptical of in terms of party system evolution/any kind of solution to our current predicament. I will leave that for some future discussion.

I do recommend the entire piece.

To what extent was the high level of ticket-splitting in the later decades of the 20th century a result of Southern states and rural areas taking longer at the state and local level to catch up to changes that had already happened at the presidential level in those places?

The 2000 vs now comparison shows just how much the internet has changed the game. People are funneled and reinforced and now “convinced” and don’t change teams for any race. It’s done. I dont see it changing until the generation currently age 10-30 comes of age, even then who knows. The VA AG race tomorrow will be a good one to watch tomorrow. If Jones wins easily then it reinforces even further the whole nothing matters anymore. In the past his mishaps would have ended his campaign.

Lot of clarity here, to sort out what we are witnessing, and the implications are stark:

But this is not taking place in a vacuum. Rightwing media has been hammering hard on political contrast to the point of complete demonization of liberals/Dems for over 3 decades. During that time, Dems continued (for the most part) to play by established precedent and attempted to “reach across the aisle.”

Now, in 2025, the sheer amount of financial resources and bandwidth of media output at the disposal of the Right to shape public opinion, is beyond reckoning with. Quality in a Dem candidate or their platform cannot bear up under that pounding. I will argue that Dems only do as well as they do, as a result of the tenacity of their voters to cling to their long held ethical values despite the deluge of rightwing disinformation.

Who knows how this plays out as older generations fade with our corporate memories.

The medium is the message Who ever controls the medium controls the massage.

@Kylopod: This is all very much of a piece with the sorting of the parties along ideological lines (broadly defined–that statement needs some clarification if I was writing a longer response). I have written several posts about the resorting of the parties first at the presidential level, then congressional, and finally filtering down to the localities. 1994 is the pivotal election for national politics. It takes well into the 2000s for it to filter into the states.

We are almost totally sorting by partisan ID, ideology (again, broadly defined), and geographically (both in terms of states but also urban/rural).

@Jc: I suspect that the internet plays a role, but what I describe in my response to Kylopod starts well before the internet.

@Rob1: Nothing happens in a vacuum. I think you are making a causal argument that I do not fully agree with, but I can’t unpack now.

I would note that what comes first, the partisan ID or the Fox News Watching? For most people partisan ID leads to Fox, not the other way around.

Many if not most of the people on this blog – writers and commenters – are former Republicans who switched because of issues. Many current Republicans are former Democrats who switched because of issues.

The number of voters who may be swayed by issues or candidates or the state of their bowels is, let’s say, 4%. We lost in 2016 by 2%. We won in 2020 by a little over 4%. We lost in 2024 by 2.5%. The battle is not for the 48% ride or die Republicans, or their Democratic counterparts. We can have 48 to 48 races from now til the end of time, and that supports your and Mr. Drutman’s thesis. But that thesis is not predictive as to the 4%, and it’s that 4% who actually elect the winner.

That 4% has thus far managed to avoid branding themselves as Blue or Red. They will for the most part probably react to economic conditions. But if the economy is not a major factor, it comes down to issues and feels and race and gender. And enthusiasm, the motivation to vote.

We lost twice with female candidates by 2% margins. Did gender play no part? Not even a 2% part?

We need to capture the floaters and motivate the true believers. Maybe down the road we can do something about structure, but for now we just need to move a handful of voters. Right now nothing else matters.

This is really the old traditional wisdom that people vote based on a perceived tribal identification. Truer now than when I first ran across it years ago.

Given this, yes, messaging and policy positioning don’t matter much to individual candidates. BUT, there isn’t much else individual campaigns can do except messaging and positioning. So they’ll keep doing it. AND messaging and positioning do matter at the Party level, at least over the long term. The problem is that Rs have, over decades and at huge expense, built a strong tribal brand while Ds have lost whatever brand definition they had. BUT building a brand requires planning and coordination that the Party won’t have until it’s imposed by a prez nominee apparent.

What is wrong with moderation is everyone gets annoyed with you. James and Steven may still recall my blogging days.

I was called a moonbat by Michelle Malkin, A far-right nut job by somebody at Daily Kos, and middle of the road by Florida politics blogger James Johnson.

Those were the days. Now I get pummeled sometimes by people who are here but none of them resemble Malkin politically.

Reposting this from the Moday forum as it seems at least tangentially relevant to the topic:

The connection to this thread being, that despite the district being an obvious”Reform winnable” (age profile a bit older than average. 93% “white”, moderately prosperous but not rich, rather below average in educationa levels, etc) the LibDems managed to rally the “centre/centre-left” vote enough to win.

Albeit on a low turnout: 30%

Similar patterns have happened elsewhere: this voter group is increasingly inclined to vote tactically to block Reform (or in the last general election, dish the Conservatives).

How far that can be read over into a more two-party and partisan US is another matter.

But its one more little indicator, imho, that centrists CAN win,

And Sam Ammar ran on a combination of “stop Reform” plus local issues.

The thing about moderation is that Bob Guillaume is a handsome man.

@JohnSF: Have the LibDems managed to resuscitate themselves since they whored themselves out to the Tories and threw away all their credibility?

Informative and instructive analysis. Nevertheless it’s easy to overlook the truism that the past is not necessarily a reliable guide to the future. While we can indulge in informed speculation about the reasons partisanship has become so entrenched this century, few predicted them in 2020. In similar fashion, it’s impossible for us today to predict what will unfold by 2050 to alter the political landscape. What we can be confident of is that we’re unlikely to have entered a new quarter century in which things remain pretty much as they are now.

I continue to believe the route to future Democratic success lies not in “winning back the working class” but in convincing the six million barely-engaged voters whose only presidential election appearance was in 2020 that politics is truly important, and they need to come back and stay engaged.

@Jc:

I plead guily to not even considering ticket-splitting in national election(s).

Why? Because while I like some of these (so-called) moderate or centrist Republicans, these days, especially in these Trump times, I find that while they talk moderation or ‘concern,’ they end up voting with Trump nearly 100% of the time. So, I have no incentive to vote for these Republicans.

@al Ameda: Feel the same. Miyares is fairly moderate as far as today’s GOP is concerned. His biggest drawback to me is his abortion stance. You see his ads and nothing about Trump and all about “representing everyone”. (eyeroll) How can anyone believe that when you align yourself with Trump? If you ask these guys to say do you agree with Trump on this or that, the dance that ensues is painful to watch. Voting for Trump is an instant spine-ectomy. Why would I even consider someone like that for AG? You basically just admitted to being another AG stooge to your “Leader”. Long and short, even if you are an appealing moderate in the GOP, you are linked to the Republic killing machine that is the current President and I can’t support you regardless of how poor the other candidates may be.

@Ken_L:

Yes, past performance is not indicative of future gain, as the commercial used to say.

But these are stark patterns, and our understanding of how institutions interact with these behavioral patterns suggests that this is unlikely to change anytime soon and is likely to deepen.

And while an exact prediction from 2000 might not exist, there is actually a lot of analysis of the problems of the democratic deficit in American politics as linked to institutional design going waaay back.

I, for example, have been complaining about competitiveness and representativeness as well as the problems with single-seat districts for pretty much the entire 20+ years I have been writing here.

So sure, things may change, but the hope for change should not obscure our understanding of how things are.

@wr:

Not only “yes”, but in many respects it may have benefitted them.

The LibDem main vote harvest at the last general election was at the expense of Conservatives, with “upper middle” centrists abandoning the Conservatives post Boris/Truss, still dubious of Labour, and scornful of Reform as pack of populist chancers and Brexiteer dimwits.

As many of such voters regarded Cameron as the last acceptable Conservative leader, LibDem association with him does them no harm.

Hence the LibDems picking up 64 seats in 2024, mostly at Conservative expense.

And came second in 91; mostly Conservative held.

Mostly again due to both Labour and Conservative “centrist” votes switching : Conservatives out of anger, Labour at hope of toppling Tories.

This is the current Conseervative dilemma: their base inclines to view the Reform challenge on the right as the key, and the answer either to move right or ally with Reform.

But in many respects the “Blue Heartland” vote is more imperilled by the LibDems then by Reform

Reform a challenger more in the old “lower middle class” Con/Lab contested seats, where the larger right wing Con vote peels off to Reform, and Reform populism also attracts some Labour and floating votes.

But the Labour position is also problematic: it can lose protest votes on the left to the Greens etc, and working class/lower middle class votes to Reform, at the same time as Conservatives also may collapse to a Reform challenge in such seats.

So both Conservatives and Labour are in dire peril of getting squeezed in two very diffrent types of constituency.