Bongino to Resign

Spouting opinions is far easier work that governing based on facts.

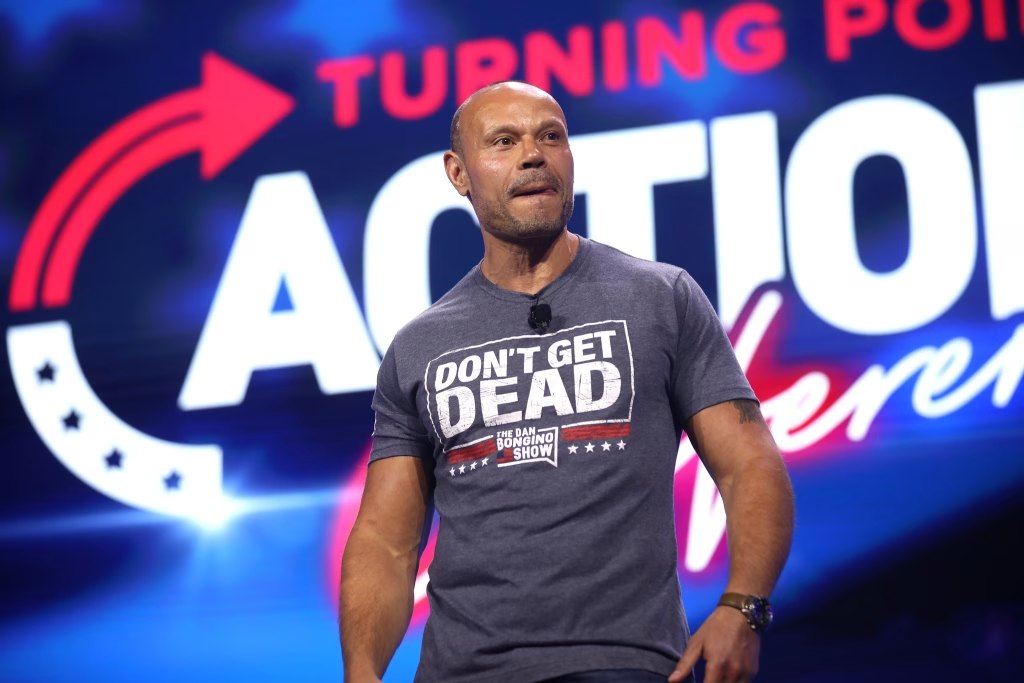

Via the AP: FBI Deputy Director Dan Bongino says he plans to resign next month as bureau’s No 2 official.

FBI Deputy Director Dan Bongino said Wednesday that he will resign from the bureau next month, ending a brief and tumultuous tenure in which he clashed with the Justice Department over the handling of the Jeffrey Epstein files and was forced to reconcile the realities of his law enforcement job with provocative claims he made in his prior role as a popular podcast host.

I am not surprised, given that roughly six months ago, he admitted to Fox and Friends he didn’t like the job. At the time, I wondered how long he would last.

“The biggest lifestyle change is family-wise,” Bongino lamented, explaining that he took the civil service job at the president’s behest.

“It was a lot, and it’s been tough on the family. People ask all the time, ‘Do you like it?’ No. I don’t,” he said. “But the president didn’t ask me to do this to like it — nobody likes going into an organization like that and having to make big changes.”

At one point during his Fox News interview, the former podcaster told an anecdote about a woman who said she missed his show.

Bongino said he told the woman, “I miss me too,” and then explained to his interviewers, “Part of you dies when you see this stuff behind the scenes.”

The video can be found here:

Tim Miller takes him to task in the video, which Bongino deserved at the time (and still does). In fact, I would recommend the video because Miller does a great job of detailing Bongino’s past statements and what he has to deal with as Deputy Director–note Bongino’s face when he was asked about the Epstein suicide. Miller also correctly called Bongino’s likely return to podcasting.

I am going to give Bongino credit for speaking the truth as to his former life versus his current life (and, I assume, his future life). Back to the AP piece linked above:

“I was paid in the past for my opinions,” Bongino said in a Fox News interview. “One day I will be back in that space but that’s not what I’m paid for now. I’m paid to be your deputy director and we base investigations on facts.”

This was a pretty candid admission. He knows he spewed something other than facts on his show. That means that he was okay, and probably still is, pretending like conspiracy theories and wild accusations are fine because they are just “opinions.”

He sounds like a poor undergraduate who thinks that having an “opinion” means it can’t be judged, but can only be accepted because, well, it’s just an opinion. A favorite gripe for students who get poor scores is that they just have a differing “opinion” from the professor. Even here on the site, sometimes commenters will counter with an argument bolstered by evidence and even assert that any disagreement is just a matter of opinion.

Side note: making a more sophisticated, analytical argument based on evidence hardl automatically makes one right, but there is a far site higher chance such an approach will be closer to right than simply making assertions because, well, that’s what one thinks is true.

A lot of unsophisticated thinkers categorize the world in “opinions” (personal views that are all equally valid) and “facts” (nuggets of information like the fact that a cow is a mammal or that the typical humanbody temperature is 98.6 degrees F). Such thinking ignores argument, analysis, and the careful deployment of evidence. It tends to reduce arguments to a version of Monty Python’s Argument Clinic sketch. He who says “No, it isn’t!” the most and the loudest wins!

One’s “opinion” might be that we should colonize the Sun, given the ample access to solar energy. The fact that such a statement is couched as “opinion” does not make it immune from criticism or shield it from being dubbed absurd and therefore dismissed.

Or, you know, you might assert that the basement of a certain pizza restaurant is being used to kidnap children, all the while ignoring the pesky lack of existence of a basement. Why clutter the head with facts and actually research when spouting opinions pays the bills and then some?

To pick a real academic example, I once had a master’s student who would literally roll his eyes when a certain International relations theory was mentioned in class. I told him that he was entitled to his view that the theory did a poor job of explaining state action, but he had to be able to demonstrate why, which requires more than just an “opinion” about the theoretical construct in question.

Likewise, we are awash with people with opinions, like Bongino (and Patel, Hegseth, RFK, Jr., etc.), who made a career out of rolling their eyes at things while not being able to actually explain much of anything.

Worse, people with provocative talk shows like Bongino’s often are barely even dealing in opinion, as much as they are trafficking provocation and fiction.

That is, of course, one helluva lot easier to do than be a serious law enforcement official who is bound by the facts.

I am going to again give Bongino some modicum of credit. He admitted that the job was hard, he had to face up to real facts like Epstein’s suicide, and he admitted (unlike some of his cohorts) that there is a difference between the “opinions” spouted by podcasters and the “facts” of being in government.

But that credit will be immediately withdrawn if (and, I think, when) he goes back to his old ways because the money is too good not to do so.

I’d love $5 for every time I’ve highlighted “I think” in a student’s assignment. I even have a comment saved in a folder along with numerous other common bits of feedback so I can copy/paste it for them: “Don’t tell me what you ‘think’. Make an argument based on evidence and logic, confident its integrity will be self-evident.”

Andrew Bailey, the man who will now be the only FBI Deputy Director, is a real piece of work. I expect he’ll be willing to do just about anything to keep Democrats out of power.

@Ken_L:

Does it not depend on the subject of the paper or the particular course? I could see some contexts wherein that advice would be sound.

But most interesting subjects contain a lot of unknown.

Facts:

-often few that are verified;

-subject to limits and interpretation;

-often lead down wildly differing paths depending on the above.

Logic:

-not one thing, there are multiple systems of logic;

-it may be unclear which form of logic is most appropriate and two different approaches may point to different answers;

-requires judgment encoding into a system via categorization/sorting, which introduces edge cases and bias;

-assumptions – hidden or known – galore.

I am willing to be persuaded about this, but it may take quite a bit. This is not equivalent to the idea that opinion is too often used as a cover for sloppy thought and poor justification.

@Kurtz: I didn’t use the word “facts”. I said “evidence”. Evidence is found in scholarly publications, which is what students are expected to read and use as the basis of their arguments. That’s the core function of a university: continuous expansion of the frontiers of knowledge by means of evidence-based research. Students are expected to demonstrate some understanding of the evidence relevant to an assignment, which is usually limited; sometimes inconsistent; seldom conclusive; and often open to different interpretations. Study guides point them to the minimum sources of evidence they’re expected to be familiar with. The better students find additional sources independently.

I don’t teach philosophy. “Logic” in my context carries the everyday meaning that arguments are justified by reference to evidence. The argument develops in a coherent manner in which each point is linked to an overall thesis. The final conclusion is consistent with the argument. It would convince a reasonable reader that the argument deserved thoughtful consideration, even if they ended up preferring a different argument.

@Kurtz: I didn’t use the word “facts”. I said “evidence”. Evidence is found in scholarly publications, which is what students are expected to read and use as the basis of their arguments. That’s the core function of a university: continuous expansion of the frontiers of knowledge by means of evidence-based research. Students are expected to demonstrate some understanding of the evidence relevant to an assignment, which is usually limited; sometimes inconsistent; seldom conclusive; and often open to different interpretations. Study guides point them to the minimum sources of evidence they’re expected to be familiar with. The better students find additional sources independently.

I don’t teach philosophy. “Logic” in my context carries the everyday meaning that arguments are justified by reference to evidence. Assertions must be verified, with whatever qualifications are appropriate. The argument develops in a coherent manner in which each point is linked to an overall thesis, which develops increasing persuasiveness as the argument progresses. The final conclusion is consistent with the argument. It would convince a reasonable reader that the argument deserved thoughtful consideration, even if they ended up preferring a different argument.

I’ll just ride one of my favorite hobby horses around the room again: we don’t teach people to think because teaching them to think will challenge existing institutions. Institutions like schools, political parties, businesses and churches. There is no profit in teaching people to think.

I’m working on a memoir. (Feel free to shudder, I understand). But it’s not just my life story, I write about writing. Not theory because WTF do I know about literary theory. I focus on what works for me, and what might work for others. I don’t prose on about muses, I prose on about the epistemology within the story. How does a character know something. Have you, the author, ensured that there is a logical chain leading to the character knowing. Is character A in the same universe of knowledge as character B. It is incredibly important when plotting to know which characters know what, and how they know it.

I tend to think of books I write in architectural terms. There’s a foundation. There are walls, some of which are just partitions, but many of which are load-bearing. There’s a decent possibility that a series I am a big part of (being evasive there, sorry) is going to be adapted for TV. I’ve watched a lot of adaptations and I see the same problem again and again: writers who don’t know the difference between a partition that can be removed, and a load-bearing wall that will collapse the house.

Peter Jackson understood. Tom Bombadil and the Old Forest were partitions. You want to tighten things up, they can be removed. But if he were to decide that Frodo didn’t need Sam the whole thing falls apart.

Opinion should be load-bearing. It should have a foundation, and it should be capable of carrying some weight. It should connect to other walls in order to enclose a space. It’s not that you’re not ‘entitled to’ your opinion, it’s that absent support and connection it’s just vapor. It means nothing. You’re just making mouth sounds. You are casting yourself as irrelevant, trivial, begging to be ignored. You’re not even a partition like Bombadil, you’re Fredegar ‘Fatty’ Bolger. If you don’t remember who that is, it’s because there’s no reason why you should.

@Kurtz: My interpretation of what @Ken_L is saying is that students will often proffer “I think” as the sum total of argument and evidence. Basically, “In my opinion, …”

But Ken can correct me if I am misunderstanding.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I think you’re correct. His reply to me fits that.

Ugh. Is it that common at the undergrad level? How long has it been this way?

@Kurtz: It was true throughout my career as a TA/grader and as a prof teaching undergrads, which would have covered ~1989 to 2016 (and encountering some of it as dean until 2024).

@Michael Reynolds:

We could do a much better job in K-12 of this, although I don’t think there is some conspiracy to stop kids from thinking.

I would state that a lot of people don’t want to learn to think, and specifically not how to construct an argument and assess evidence. Because that’s work.

It is the same reason, in some ways, people don’t learn plumbing or how to be an electrician–it requires a lot of work.

People tend to learn what benefits them in a more narrow lane of day-to-day life. This is less due to conspiracies to keep the masses in line and more due to the fact that most people, including students at universities, only want to put in the energy needed to get whatever it is that they are after.

Cs get degrees, as the saying goes.

It should not be a surprise that most people are average thinkers. It is how averages work (or to be even more specific, half of all thinkers are worse than the median thinker, and only half are better).

@Steven L. Taylor:

The conversation I had with @Ken_L is strange, considering one of my earliest comments was critical of the opinions cannot be wrong view. I think you and I have discussed it either in comments or privately.

I think I got hung up on the details of the first post and missed Ken’s point.

And I like to argue.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I was told not to think on several occasions when I was a kid. Most directly in Sunday School, but also at school school. Granted I was a pain in the ass, but in IIRC sixth grade, somewhere around there, when I was in Virginia schools getting the southern view of the Civil War. (Tariffs? The Civil War was fought over tariffs?) Then, maybe ninth grade? For some inexplicable reason they were trying to teach analysis of the transcendentalist writers. You can guess how that went. Also 10th grade debate club. There are plenty of examples I can think of. And when I was briefly in junior college in a philosophy class.

Yeah, there was quite a bit of, shut up Michael and just do the thing we asked you to do. In Sunday school I was informally but unsubtly invited not to come back. I have some sympathy for the poor woman who’d no doubt been dragooned into teaching SS.

My eldest carried on the ‘tradition,’ and even in a Marin County school in the 21st century (as opposed to the 19th, when I was in school) there was a lot of, please stop deconstructing everything. I’ve told this story before, but I was picking her up from school, 10th grade, Redwood High in Marin, and saw some teacher remonstrating with her, then, a few minutes later, slinking off. The guy had called her out for cursing and been treated to a compact, five minute lecture full of direct quotes from the school manual, various court cases and of course the constitution. And there was an earlier private school where she reduced a teacher to literally – not making this up – throwing a paper on the floor and stomping on it. The principal called us in actually thinking we’d discipline her. Dumb fuck.

School doesn’t teach you how to think. It’s not a conspiracy, it’s just a machine that wants to keep grinding on without being disrupted. And churches make no bones about telling you to stop thinking.

@Michael Reynolds:

You see, that is a different claim than:

One is specific, the other universal.

Not only that, one is personal, the other broadly societal.

I think this gets to the heart of some of our conflicts over the years, like the whiol cult thing. It is less that I disagree in whole, it is that I object to the way you make broader, universal claims (often based on your own personal experience).

Do I agree with you that there are people out there, maybe even a lot of them, who discourage thinking? Of course. Just like I agree that there are elements of MAGA that are cult-like, while still finding notions that Trump is explainable simply because the GOP is a cult is analytically problematic as a conclusion.

Were I feeling snarky (and I might just be), I would note that it is sloppy thinking to extrapolate universal conclusions from a handful of individual experiences. Further, it is unwise to make broader, universal statements about what is, or is not, happening in the wide world based on personal experience.

FWIW, I can share a similar story about my youngest, who used a mild curse–“Hell,” I think (we are, after all, oin Alabama)–and got called into the vice principal’s office, and it became a similar debate about school policy and the First Amendment, which eventually led to him being set free without punishment, but leaving the administrator quite flummoxed.

The main lesson I take from the combination of our anecdotes is to assert that it is probably not surprising that the children of writers and/or professors might have learned to be argumentative. Or, more likely, it should be no shock that your kid and mine know how to verbally tussle. 😉