A Comparative Note on Prisoner Voting

Sanders' suggestion is not as outside democratic norms as one might think.

As James Joyner noted earlier today, Bernie Sanders is arguing for the enfranchisement of incarcerated prisoners. This is, as James suggests, outside the mainstream of American political thought on the subject, especially given the fact that in many cases these individuals do not have their voting rights restored once they have served their time in prison.

Note the quote from Sanders in the article that James cited:

“In my state, what we do is separate. You’re paying a price, you committed a crime, you’re in jail. That’s bad,” he said. “But you’re still living in American society and you have a right to vote. I believe in that, yes, I do.”

Sanders is referring to the fact prisoner in Vermont (and in Maine) already have the right to vote from behind bars. As such, he is less proposing some wild new notion, as much as he is arguing for the expansion of a policy that already exists in the United States, albeit on a limited basis.

The National Conference of State Legislatures breaks down felon voting rights as follows:

*In Maine and Vermont, felons never lose their right to vote, even while they are incarcerated.

*In 14 states and the District of Columbia, felons lose their voting rights only while incarcerated, and receive automatic restoration upon release.

*In 22 states, felons lose their voting rights during incarceration, and for a period of time after, typically while on parole and/or probation. Voting rights are automatically restored after this time period. Former felons may also have to pay any outstanding fines, fees or restitution before their rights are restored as well.

*In 12 states felons lose their voting rights indefinitely for some crimes, or require a governor’s pardon in order for voting rights to be restored, or face an additional waiting period after completion of sentence (including parole and probation) before voting rights can be restored.

NCLS: Felon Voting Rights

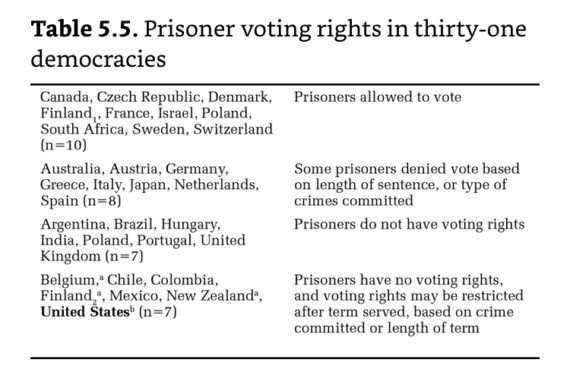

We can further go international:

So, it really isn’t unusual, in the grand scheme of democratic governance, for prisoners to be allowed to vote. Ten well established democracies allow it fully, and eight additional cases allow some voting rights. By the same token 14 cases deny prisoners the right to vote, with half of those having some post-prisoner strictures being possible. Most of those deny voting rights to those convicted of voting-related crimes (and even then, it is only temporary). The US is the only case wherein it is possible to have one’s right to vote permanently taken away.

The topic of prisoners voting is not one I have an especially strong opinion regarding, insofar as I can see the argument for cessation of a large swath of civil rights as a result of incarceration. Obviously, one is curtailed in one’s right to association in prisoner. Likewise free speech is curtails, and so forth. As such, stating that one cannot vote is not outside the general parameters of a prisoner sentence. (I do, however, strongly believe that prisoners should have voting rights automatically restored once a sentence is served).

Still, I can see the argument that elections will have consequences for prisoners, and that they are still citizens, even if curtailed ones. Indeed, one could easily connect my post yesterday on democratic responsiveness, as well as James’ post on the condition of Alabama prisons from last week and reach the not unreasonable conclusion that letting prisoners have some small voice might help at least draw attention to people who are otherwise forgotten about. The question of felons voting is very much connected to a broader question of what the purpose of a prison sentence is. We often talk the language of rehabilitation, but the objective reality is that we see it as punishment (and the way society often cavalierly jokes about things like prison rape underscores this fact). If we really want prisoners to emerge from prison and start acting like real citizens, it might not be a bad idea to give them some connections to broader society while in prison.

A related note to this is the degree to which our prison system is linked to racial issues. We know, for example, that African-Americans make up a disproportionate number of felons. According the Federal Bureau of Prisons, 37.8% of federal inmates are African-American as opposed to making up only 13% of the broader population. This certainly matters in terms of post-imprisonment, especially when felons are not automatically enfranchised again once their prison term is over.

We know that laws about felon disenfranchisement were linked to race. For an overview, see the Brennan Center report: “Racism & Felony Disenfranchisement: An Intertwined History.” Further, there was the practice of using arrest and imprisonment of African-Americans to press them into servitude from the late 19th into the early 20th centuries. See this review of Slavery by Another Name for the basics.

Fundamentally we have not come to gripes with the racial elements of prisons, let alone that of prisoner voting. Still, it is worth keeping in mind that Sanders’ proposal is not as radical as it sounds to most Americans if one looks at the global context and, further, we have to be aware of exactly how exceptional we are in this arena (and why).

Great post Steven. And I’m glad you noted that Maine and Vermont currently allow voting in prison.

Something that I mentioned in my response to James’ earlier post from this morning I think is particular worth considering is how prison populations accounting can be used to help preserve political power. In many states, one reason that smaller communities have political power are agreements to count the inmates as residents of that community versus where they came from. In New York State, at least, that enabled rural Republicans to have an outsize presence relative to their permanent populations for many years.

Does that mean, necessarily, that those inmates should be able to vote in local elections? I’m not sure. It does demonstrate how they are often used to prop up parties/candidates that are not necessarily representing their positions (and whose political power rests upon not changing status quo around mass incarceration).

That’s before we get into the entire race issue and the serious role that plays in disenfranchisement of over-policed communities.

@mattbernius: This is a great point: we count residents when talking about the apportionment of political power. That actually strikes me as a further reason to consider letting prisoners vote.

I do think this

is a useful point.

At the end of the day, I’m not sure I want murderers, rapists, and robbers having a voice in policy-making. Still, part of the problem here is that way too many of the people incarcerated in our prisons and penitentiaries aren’t guilty of those sort of crimes. Things like “three strikes” laws and “mandatory minimum” sentences have far too many locked up for relatively paltry offenses, most of which are drug-related.

@James Joyner:

On one level, I get that. On another, this is (as you somewhat note) that prison is not just a holding pen for the worst of the worst. This really gets to serious issues for criminal justice in the US: are prisons holes in which we throw people to suffer for their crimes (and to protect the rest of us from them, at least for a time) or are they supposed to produce people who can reintegrate into society? How bad of a crime is bad enough to say you shouldn’t have a say?

As I noted, I do not have a especially strong view on this. I tend towards maybe 60-40 in favor of letting prisoners vote. I am certain, however, they ought to be allowed to vote once their sentence is served.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Agreed.

Honestly, voting rights are pretty low on the list of concerns I have about the system. We lock up far too many people for whom some sort of rehabilitation, community service, or other program would be more useful. And the conditions in which we house people are pretty deplorable across the board. The prison rape is both so common as to be a joke and yet treated as though it’s, well, a joke is just shocking to me.

@James Joyner: I totally agree. Reading the reports about Alabama’s prisons is sickening. Worse, I already knew a lot of it, as our Center for Public Service did a survey project of men’s prisons for the DOC.

@mattbernius beat me to the basic point, but I wanted to say that this ties into the recent posts on how slaves were (partially) counted as people in order to give the South extra political power.

I started to write this in response to James’s earlier post but never quite managed to hit the post button:

Now hearing that some towns do in fact get to count local inmate populations as part of their own, then it seems like justice itself to allow the inmates a say in local affairs.

If I look at a generic prisoner, then I’m hard pressed to think of what mischief he might accomplish by weighing in on the choices presented on election day. If people are afraid that prisoners might actually sway the outcome, well that assumes that they are numerous enough to represent an oppressed class. That’s an interesting thought.

In Puerto Rico many years ago, it was found that prisoners voted in block for favors granted by politicians, enforced by violence. So no, I’m a progressive in most issues and support voting rights for all adult citizens, but allowing actual prisoners to vote is very perilous.

Couple additional thoughts…

In addition to looking at other country’s voting right for incarcerate people, its also worth looking at their sentencing practices (see for example: http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/sentencing.pdf). The reality is that we sentence a wider range of crimes to longer stays in prison. That really needs to be taken into consideration. Especially when we look at the racial vector and how that has the potential for swinging close races.

Also, its worth noting that “t0ugh on crime” laws have led to an increase in indirect “violent crime” convictions (i.e. places where an accomplice doesn’t even need to be immediately present to a murder to be charged with murder or the move to charge drug dealers or the people giving the drug with murder in cases of ODs).

@James Joyner:

I understand this perspective and the points you are raising. However, because criminal justice policy is set at the state legislative level, and often those elections are arguably where small numbers can make a really major difference. So while we often think primarily about national elections, state/local are really what matters when it comes to most CJ issues. From that perspective voting rights become really important (especially in states where up to 1/3rd of all black men cannot vote due to prior convictions).

Understood. Yet at the same time, the vast majority of those individuals will eventually be reentering society. And, unless exonerated, their past actions will always have happened. So at what point are they to be reintegrated.

Further, and this is admittedly very much a CJ move, but the key missing word in that sentence is *convicted* murderers, rapists, and robbers… The reality is, given the relatively low rate of solved cases, murderers, robbers, and especially rapists are always, already regularly involved in policy making (at least as voters, if not literally as policy makers).

@James Joyner:

If I’m reading the numbers right, there are 6 or 7 million Americans in prison or on parole or on probation. Let’s say conservatively 5 million additional voters. Let’s say they split 60-40 for one particular political party. That’s a delta of 1 million votes of popular vote margin. And I’m not yet counting ex-felons who have lost the franchise permanently. That sounds like a pretty big deal to me.

I keep waiting for someone else to make this joke, but apparently everyone else has enough common sense or self restraint not to…

@James Joyner:

Dude, we’re not talking about letting Mexicans vote.

——

I just can’t hear “murderers, rapists…” without hearing Trump. I just can’t. The man ruins everything, including, somehow, murderers and rapists.

I definitely think ex-cons should have their voting rights restored upon release, but voting rights while still in prison seems like a recipe for corruption and violence to me. Prison gangs, corrupt guards, etc. would have huge incentives and almost unfettered power to coerce prisoners to vote however the gang or guard(s) want.

While I get the corruption concerns, I think the fact that we have those concerns underscores the problems we have in out prisons. Corrupt guards should not be the default assumption, nor should gang dominance. And yet, they rightly come immediately to mind.

There is the also the question of how this works in Maine and Vermont.

Well, speaking as a Vermonter, I’d say it’s because we’re an unusually awesome state.

More seriously, I take your point that we shouldn’t simply presume that the existence of gang violence and official corruption would make voting rights untenable, nor should we accept that as a continuing state of affairs even if it is the present reality. That said, though, I would still argue that it’s a serious concern and should, at the very least, be carefully weighed and assiduously guarded against before enacting any prison voting program.

@R. Dave:

That’s a pretty simple recipe for corruption.

Corruption:

* add in corrupt guards

Serve while warm. Feeds entire prison population (if not the entire country).

If voting rights are fundamental, then a country’s corruption can hardly by an answer against.