‘Affirmative Action for the Rich’ in College Admissions

After other controls are applied, household income is still a huge advantage.

NYT/The Upshot (“Study of Elite College Admissions Data Suggests Being Very Rich Is Its Own Qualification“):

Elite colleges have long been filled with the children of the richest families: At Ivy League schools, one in six students has parents in the top 1 percent.

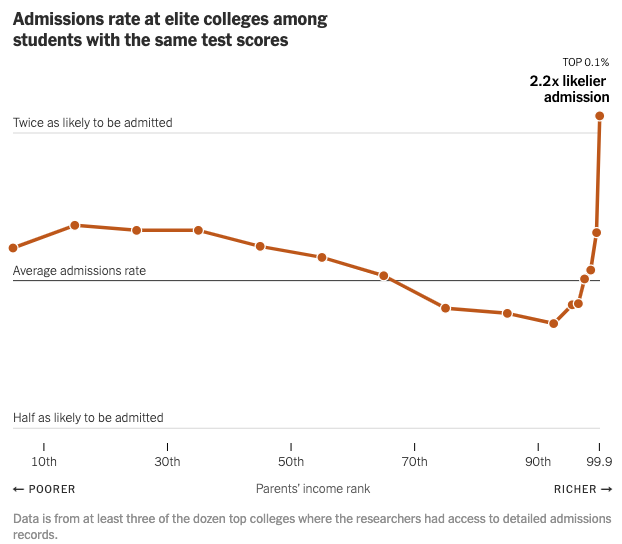

A large new study, released Monday, shows that it has not been because these children had more impressive grades on average or took harder classes. They tended to have higher SAT scores and finely honed résumés, and applied at a higher rate — but they were overrepresented even after accounting for those things. For applicants with the same SAT or ACT score, children from families in the top 1 percent were 34 percent more likely to be admitted than the average applicant, and those from the top 0.1 percent were more than twice as likely to get in.

The graphic is rather stark—and shows a somewhat different picture:

So, having very wealthy parents is, in and of itself, seemingly a huge advantage even apart from all of the advantages that otherwise accrue to those children in terms of private schooling, test preparation, the ability to pad resumes with extracurriculars, etc. At the same time, those in the six lowest deciles also have a significant—albeit not nearly as large—advantage, while those from the upper middle class and moderately wealthy households are actually punished slightly.

The study — by Opportunity Insights, a group of economists based at Harvard who study inequality — quantifies for the first time the extent to which being very rich is its own qualification in selective college admissions.

The analysis is based on federal records of college attendance and parental income taxes for nearly all college students from 1999 to 2015, and standardized test scores from 2001 to 2015. It focuses on the eight Ivy League universities, as well as Stanford, Duke, M.I.T. and the University of Chicago. It adds an extraordinary new data set: the detailed, anonymized internal admissions assessments of at least three of the 12 colleges, covering half a million applicants. (The researchers did not name the colleges that shared data or specify how many did because they promised them anonymity.)

The new data shows that among students with the same test scores, the colleges gave preference to the children of alumni and to recruited athletes, and gave children from private schools higher nonacademic ratings. The result is the clearest picture yet of how America’s elite colleges perpetuate the intergenerational transfer of wealth and opportunity.

“What I conclude from this study is the Ivy League doesn’t have low-income students because it doesn’t want low-income students,” said Susan Dynarski, an economist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, who has reviewed the data and was not involved in the study.

In effect, the study shows, these policies amounted to affirmative action for the children of the 1 percent, whose parents earn more than $611,000 a year. It comes as colleges are being forced to rethink their admissions processes after the Supreme Court ruling that race-based affirmative action is unconstitutional.

“Are these highly selective private colleges in America taking kids from very high-income, influential families and basically channeling them to remain at the top in the next generation?” said Raj Chetty, an economist at Harvard who directs Opportunity Insights, and an author of the paper with John N. Friedman of Brown and David J. Deming of Harvard. “Flipping that question on its head, could we potentially diversify who’s in a position of leadership in our society by changing who is admitted?”

Given that getting into these schools is much harder than graduating from them once admitted, and that their lifetime branding and networking advantages are considerable, the admissions departments of these schools have an incredible amount of power in choosing our elites. The overwhelming number of people who even bother applying to these schools are highly capable young people.

I continue to believe that admissions to the top schools—and, I must once again emphasize that we put wildly disproportionate emphasis on a handful of selective schools in our conversations about higher education—should be on a lottery system. There could be a relatively objective set of criteria applied to select the most capable applicants and then randomize the selection from within that group.

The schools say they’re trying to remedy the problem:

Representatives from several of the colleges said that income diversity was an urgent priority, and that they had taken significant steps since 2015, when the data in the study ends, to admit lower-income and first-generation students. These include making tuition free for families earning under a certain amount; giving only grants, not loans, in financial aid; and actively recruiting students from disadvantaged high schools.

“We believe that talent exists in every sector of the American income distribution,” said Christopher L. Eisgruber, the president of Princeton. “I am proud of what we have done to increase socioeconomic diversity at Princeton, but I also believe that we need to do more — and we will do more.”

My strong suspicion—and I haven’t taken the time to read the study itself—is that the skew is relatively non-nefarious in intent, even while it’s pernicious in impact. As the graph shows, there’s clearly a strong attempt to let in students from relatively disadvantaged households. Those in the bottom deciles are getting in at a higher rate than their packages would merit. At the same time, the combination of legacy admissions and a desire to admit students who will pay full freight rather than requesting financial aid is likely skewing the selection rates at the very top.

This is interesting as well:

The new data showed that other selective private colleges, like Northwestern, N.Y.U. and Notre Dame, had a similarly disproportionate share of children from rich families. Public flagship universities were much more equitable. At places like the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Virginia, applicants with high-income parents were no more likely to be admitted than lower-income applicants with comparable scores.

The incentives are flipped at the state schools, who are trying to increase their prestige levels by competing for the best students. To the extent that they’re trying to pad their income stream, they do so by admitting foreign and out-of-state students who pay much higher tuition rates.

And getting back to an earlier point:

Less than 1 percent of American college students attend the 12 elite colleges. But the group plays an outsize role in American society: 12 percent of Fortune 500 chief executives and a quarter of U.S. senators attended. So did 13 percent of the top 0.1 percent of earners. The focus on these colleges is warranted, the researchers say, because they provide paths to power and influence — and diversifying who attends has the potential to change who makes decisions in America.

They also reinforce prior research:

The researchers did a novel analysis to measure whether attending one of these colleges causes success later in life. They compared students who were wait-listed and got in, with those who didn’t and attended another college instead. Consistent with previous research, they found that attending an Ivy instead of one of the top nine public flagships did not meaningfully increase graduates’ income, on average. However, it did increase a student’s predicted chance of earning in the top 1 percent to 19 percent, from 12 percent.

For outcomes other than earnings, the effect was even larger — it nearly doubled the estimated chance of attending a top graduate school, and tripled the estimated chance of working at firms that are considered prestigious, like national news organizations and research hospitals.

“Sure, it’s a tiny slice of schools,” said Professor Dynarski, who has studied college admissions and worked with the University of Michigan on increasing the attendance of low-income students, and has occasionally contributed to The New York Times. “But having representation is important, and this shows how much of a difference the Ivies make: The political elite, the economic elite, the intellectual elite are coming out of these schools.”

The top graduates at Harvard and Princeton aren’t much different in terms of aptitude from their counterparts at Michigan or the University of Virginia. And they all do quite well later in life.

Still, of the nine justices on the US Supreme Court, only one (Amy Coney Barrett) lacks an Ivy League degree (and she went to Notre Dame, not a state flagship). Everything from Supreme Court clerkships to internships at the New York Times is skewed toward the top handful of schools. Not just because they’re able to select from the very best students but because of the aforementioned branding and networking connections. As good as the best state schools are, their professors are much less likely to be able to call up a Supreme Court justice or the editor of the Times to lobby for their graduates.

There’s actually quite a bit more to the article, which breaks down the study much further. It’s worth a read.

Did anyone attempt to quantify how much of this effect is due to preferences for children and grandchildren of alumni? Way back when I was picking schools, the best way to get into Harvard was to be the son of a Harvard grad. I don’t know whether that is still as true.

The equation can often resemble the following: 1) can this family pay full tuition and not tap into our financial budget, so we can use said financial aid budget on more-in-need families, and 2) can we get this family to be donors during and after their kid’s time with us?

The student’s actual aptitude is a nice-to-have, but not always a need-to-have, in this scenario.

@Long Time Listener:

The richer you are, the better the customer is the equation for most scenarios. College is a business and business requires profit and repeat customers. Yes, wealth tends to limit the number of kids you have but it also means you can subsidize or outright pay for those kids’ 4-12 years of higher ed. The problem with donors is it’s become less of “we give to get our name on the building and our underachieving kid has a nicer dorm” to “the kid’s a moron and he’d never get into pre-K without my cash”.

What is NOT “non-nefarious” is the rigorous work being done to prevent the disadvantaged from getting a leg up against this “non-nefarious” intent.

Decades of railing against affirmative action has been for a reason; to maintain the privilege of the elite, who have no intention of sharing with others.

The family having made it, these schools are an important part to maintaining family status and wealth. The “ring-knocker” (alumni cronyism) is very impactful on a career. Not to mention the value of the credential as a signal and the networking while attending are valuable for bureaucratic jobs that depend on selection by higher ups.

Given how many alum they have in media and pundity, the Ivy propaganda is constant. An added elite fetish on top of the college fetish.

I once saw a comment by a PhD student (non-STEM) at a not top tier program about how all the professors had Ivy degrees. Which made me wonder what job prospects such student might have given their own college didn’t hire PhDs from programs at their level.

What that graph says to me is not that the lower half of income rank is getting the shaft but that the upper half minus the 1 percent is getting turned away.

@Daryl: Affirmative action’s impact on whites is relatively negligible and at the bottom of the admission pool—but seems obviously unfair to those thus denied. What seems to be happening is that being rich and/or the child of an alum is that it means that if you’re well qualified, you’re going to get in rather than it being luck of the draw.

@Jay L Gischer: That’s my take as well: it’s really the 70th through 90th percentile being hurt here.

@Jay L Gischer: I’d be interested in what the absolute numbers are, rather than percentages. And, since there is this thing called “google” here it is: (Interpolating from a chart without gridlines)

0-20th percentile – 3%

21-40th percentile – 6%

41-60th percentile – 10%

61-80th percentile – 14%

81-90th percentile – 14%

91-95th percentile – 15%

95-99th percentile – 25%

99-99.9 percentile – 12%

Top 0.1 percent – 2%

Given that Harvard’s endowment is such that they claim they don’t consider ability to pay in admissions, it seems pretty obvious that its primary function is to select the elite amongst the privileged and ensure they and their families retain power from generation to generation. This is especially true given the study a few years ago that looked at students admitted to elite schools who instead chose to go to non-elite schools which showed that they fared just as well in their life and careers as those who attended the elites (unfortunately, my google fu has failed me for now).

Oh, and the numbers presented are even more skewed than they first appear. It turns out that more than 2/5ths of Harvard admissions fall outside the strictly merit-based system they pretend to:

@Long Time Listener:

You nailed it. Admissions offices LOVE full-pay students.

As long as the Ivy League disproportionately select students from private high schools you will continue to have an elitist problem. Last time I checked, 90% of students attend public schools, yet Harvard student population is 70% public. What does that mean? If you go to a private school you increase your chances of getting accepted to Harvard by 300% (3 times). That’s rather significant.

@James Joyner:

Remember – this data is pre-SCOTUS Affirmative Action Activism.

The poor and minorities are denied the advantages of generational wealth, and the recent SCOTUS decision insures that it continues, or even gets worse. Increases inequality; the left half of the graph will likely go lower.

Rich and non-minority means you have all the advantages of generational wealth and the recent SCOTUS decision insures that it continues, or even gets more advantageous.

Increases inequality; the right half of the graph likely goes higher.

Happy to see some schools, like Wesleyan here in CT, eliminating legacy admissions in the face of the SCOTUS decision.

@Raoul: As long as there is humanity, we will continue to have an elitist problem. Humans will always want to put themselves over their peers whenever they can. I had the same experience being a working class kid (with, fortunately, a working class union contract job) when I went to a private Christian college back in the 70s. The only difference was who the elite were. But we had them, too.

@DrDaveT: The NYT Briefing that I get each morning included some quantification:

“Legacy is a major advantage. These colleges are inundated with strong applications. When admissions offices are making close calls among students with similar transcripts, legacy status acts as a trump card. About half of legacy students at these colleges would not be there without the admissions boost they receive.”

Elite colleges have one overriding goal – maintain their place and status as elite colleges. Everything takes second place to that. Money and legacies serve that end. The bullshit Harvard made up to keep Asians out served that end. The schools picking rich first generation black immigrants to pad their “affirmative action” numbers serves that purpose end.

They would never agree to that. Status and exclusivity is what they are “selling.” That model would threaten the finances of the institution by not allowing them to keep growing their endowments while making the education “free” to the non-rich students.

Considering the number of “qualified” applicants, they could quadruple enrollment without sacrificing student quality. But of course, that will never happen either. The value of a Harvard or elite education is the exclusivity.

BBC America was reporting tonight that Harvard’s legacy admissions policies are under scrutiny because they perpetuate racial inequities. Whodathunkit?