Canada and Single-Seat Plurality Elections

Canada has more parties than the US, but still suffers representation problems due to FPTP elections.

On a recent installment of the FiveThirtyEight Podcast, Nate Silver quipped about the Canadian elections:

Nate: I didn’t know that Trudeau lost the popular vote

Crosstalk/someone else: Yeah, very narrowly in eighteen.

Nate: Oh, how come people don’t complain about that more? I don’t hear many Trudeau-loving progressives point out that that their guy actually lost the popular vote.

Now, this was the cold open and not part of a broader conversation and the punchline was basically “this is the part of the podcast where we all learn for the first time that political actors are opportunistic.” And I will note a minor correction: it wasn’t the 2018 elections, it was 2019.

I have zero dogs in the “Trudeau-loving progressives” fight but will say that Canada’s electoral system is producing problematic outcomes from the point of view of representativeness. Specifically, in 2019 and in the 2021 elections (pending final counts) the party that won the most votes nationally did not win the most seats in parliament. Moreover, both 2019 and 2021 will require minority governments.

So, yes, this is problematic and is an example of why electoral rules matter and, specifically, how single-seat districts are detrimental if one wants a system that produces representative outcomes.

First, some basics.

Canada has a parliamentary system with a bicameral legislature with medium symmetry between the chambers.* The House of Commons is elected via single-seat districts with plurality winners (just like the United States, but they have more parties than we do), while the Senate is composed of members appointed by the govern-general on the advice of the prime minister. The Senate functions more like the British House of Lords than it does the US Senate. The Canadian Senate’s main legislative power is the power to veto bills passed by the House of Commons, which they do on a relatively rare basis.

The head of government is the prime minister and the government is chosen out of the House of Commons, the lower chamber of the bicameral legislature. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, meaning that Canada is not a republic, but is, instead, a constitutional monarchy. It is also a federal system.

Side note: for those who like the “republic, not a democracy” debates, Canada is a democracy, but not a republic! (And the US is both a republic and a democracy). I would also note that Canada is very federal, and yet doesn’t have a presidency, nor an electoral college, nor a Senate that gives outsized power to its smaller sub-units (because despite what some American commentators say, none of those things are inherent to federalism).

In a parliamentary system, the government (the PM and cabinet) is formed by the party (or parties) that control a majority of seats. Sometimes, however, a party with the plurality of seats (the most, but not 50%+1) forms a minority government. This happens when a smaller party agrees to support the plurality party in terms of government formation but does so without forming a coalition government.

A minority government would still need to form alliances to pass legislation and, by definition, are more limited in what they can accomplish than if they had the most seats in parliament.

It should be clear that minority government is not, in and of itself, minority rule. Again, majority support is still needed to form that government, and all legislation still has to pass with a majority of votes.

The problem in Canada is that the single-seat districts with FPTP, especially since they have a lot of parties (which, BTW, is an example of why Duverger’s Law isn’t much of a law)** produces outcomes wherein the party with the most votes does not win the most seats.

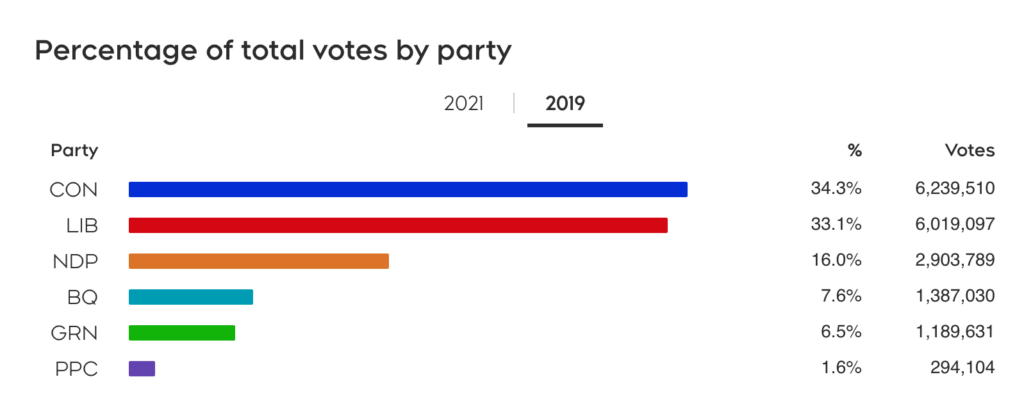

Note the 2019 vote totals (source):

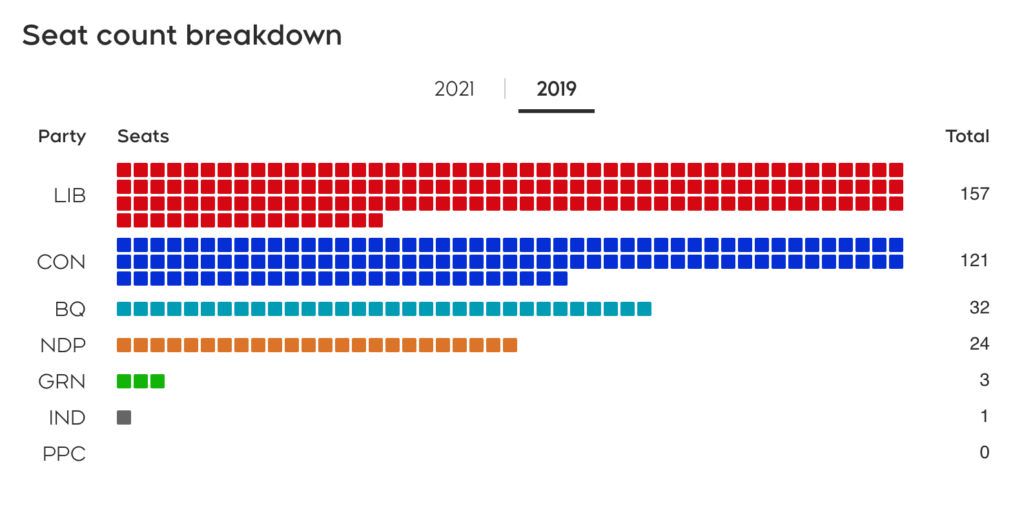

However, the seat distribution was 46.45% (and a minority government with the help of the NDP):

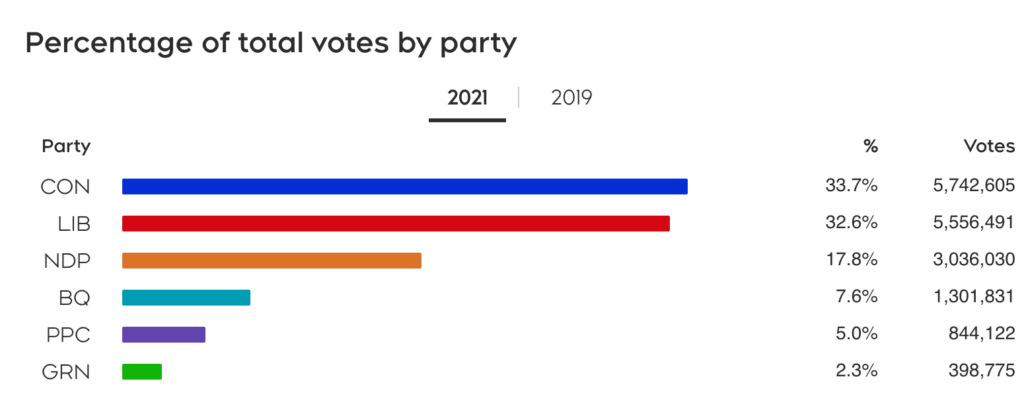

And a similar outcome for 2021:

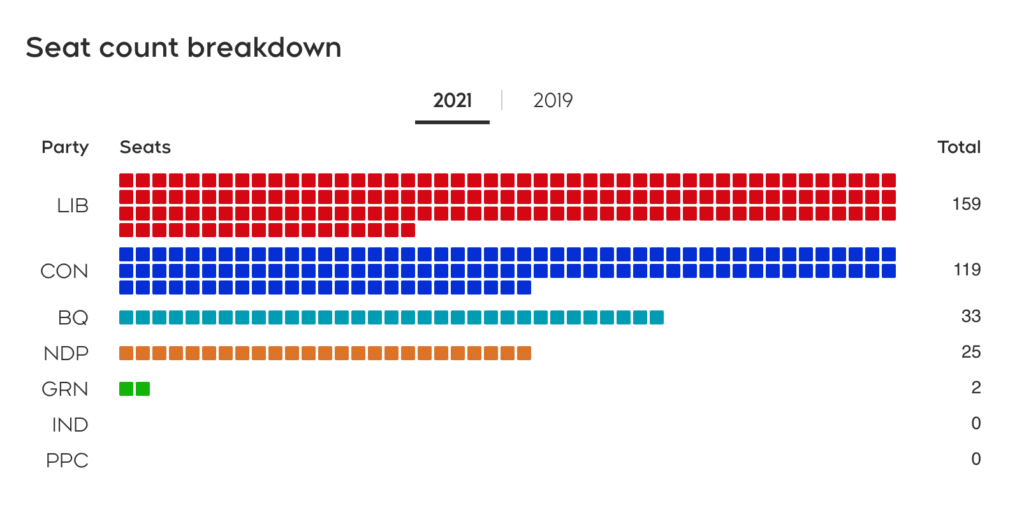

So, all the time, effort, and money to run an early election seem to have netted Trudeau’s Liberals 2 seats and still only a plurality of the House of Commons (46.75% of the seats) and, therefore, another minority government.

Quite frankly, from a theoretical point of view, Canada needs electoral reform. But, of course, the two largest parties benefit from the current system (the Liberals, for example, are able to turn less than a third of the vote into a plurality of seats into minority government). A proportional representation system, which would better match Canadian’s political preferences, would cut into the Liberal (and the Conservative’s) seat shares, so they are unlikely to want to change the situation.

For more on Canada, see Matthew Shugart at Fruits and Votes:

- Canada 2021: Another good night for the Seat Product Model, and another case of anomalous FPTP

- What electoral system should Canada have?

*The US has fully symmetrical chambers when it comes to legislative power (i.e., all legislation must pass both chambers in identical form to become law and, with the exception of new spending measures, bills can originate in either chamber). Medium symmetry means that one chamber has more legislative power than another, but that the chamber with lesser power still can affect legislative outcomes, usually by vetoing or delaying (e.g., the main power of the British House of Lords is delay). In some cases, the lower chamber has special powers, such as over the budget, that the upper chamber has no say in. In asymmetrical cases, the upper chamber lacks a veto over legislation (i.e., the lower chamber can legislate on its own).

**Duverger’s Law, in simple terms, is the idea that single-seat FPTP leads to a two-party system. However, Canada, the UK, and India, to name three such systems, undercuts that notion. The US fits the mold perfectly, but the US has what those systems do not: primary elections.

Oh, Canada…

*Cough* my Canadian wife would like to say a few things:

[Insert Canadian accent here, eh] Canadians will decide if we need electoral reform, thanks. Nobody has a problem with FPTP except for a handful of poli-sci professors and the NDP which can’t believe they have to work harder for votes. The Liberals and CPC are major parties because they’re in it to win and work hard for it. Greens are imploding (leader is resigning today) and the nut cluster PPC didn’t do nearly as well as they polled.

Actually Canada’s system works in one way much better than America’s: nut clusters stick with the GOP whereas in a parliamentary system they can set up their own party; it’s a safety valve. [Canadian wife goes back to laptop, eh.]

I argued her out of the comment that Americans these days got no business telling other countries how to run their political systems.

Canadian here. Polls show most Canadians would like to get rid of the FPTP (the only exception being a number of conservatives, because right wing voters are outnumbered by centrist and left wing voters — with the caveat that right wing in Canada would be moderate Democrat in the United States given that even conservatives here love public healthcare, don’t want to spend much on the military, and for the most part are pro-choice).

The problem is there are quite a few flavors of election systems out there, from ranked ballot to a number of flavors of proportional representation, and voters are split between them. There have been provincial referendums on replacing FPTP and none have gotten over 50% because of the disagreements on which flavor to use.

@Not the IT Dept.:

She is more than welcome to do so. 🙂

But, as @George notes, there are a lot of Canadians who do want to change the electoral system (which I did not get into in the original post, but thought about it).

Yank, or not, I would argue that a system that allows the party with the second most votes to govern is a problematic one, yes?

FWIW, from 2019:

Of course, at one point the Liberals were saying they would pursue electoral reform, but I think they did the math and realized it would harm them considerably.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Definitely yes. The problem (up here) is coming up with a replacement that over 50% of people -(assuming it’d be passed by referendum which isn’t necessary but is the way provincial efforts have been run) can agree on.

I’d personally be okay with several variants of proportional representation (which probably says a lot about what parties I vote for — Green Party and NDP would gain the most by that, though I’d argue they’re also the fairest), but don’t like the ranked ballot system Trudeau wants.

@Steven L. Taylor:

“Of course, at one point the Liberals were saying they would pursue electoral reform, but I think they did the math and realized it would harm them considerably.”

Trudeau ran on pursuing electoral reform in 2015, and in fact promised if he won it’d be the last federal election under FPTP in Canada. He won, but then noticed that he gained a majority in the House of Commons with just 40% of the vote, which seems to have adjusted his thinking. Yes, its hard not to be cynical about that. He then said he wanted ranked ballot, since that tends to favor the central party (ie his party, the Liberals), but that wasn’t popular except for Liberals, and isn’t much better than FPTP.

I defy anyone to claim with a straight face that their party wouldn’t have called an early election at a time that seemed strategically advantageous. Trudeau did, but didn’t get the majority he seemingly wanted (despite the fact he actually is not on record as having that as a goal, it’s pretty obvious). That said, the counterargument to the many who insist Trudeau won nothing by calling an election is that he did gain a couple years on his next mandatory election call. And he arguably showed all other parties that if they move to collapse the government and have another early election on a non-confidence vote, they will lose.

As to electoral reform, sure they ran on it (and a host of other things), but I think not only did the Liberals realize that it might not be to their advantage, but they also realized it’s almost impossible to achieve to everyone’s satisfaction, since each party will seek the reform that helps them, and hurts the others (like George said).

The Liberals did not win a plurality of the popular vote, but the UCP, as much as they might trumpet their marginal victory there, can’t take a lot of comfort. They, plus the People’s Party, were pretty soundly beaten by the Liberals/NDP/Green vote. The left side of the ledger wins, in other words. The Conservatives also benefited from the fact the NDP’s popular leader attacked Trudeau a lot more than his natural enemies, O’Toole and Bernier, since he likely felt he was fighting for the same voters.

The Bloq is a unique animal, so we won’t count them on either side of the spectrum.

@Pylon:

Against that Trudeau lost a great deal of good will by calling an election in the middle of a pandemic, especially since his minority gov’t was very safe (no one was going to bring in any kind of non-confidence vote).

I think he’d have been given a majority under normal circumstances (that’s the pattern for reasonably successful minority gov’ts in Canada, after a couple of years calling an election and gaining a majority). But given that one of his (fairly reasonable) claims was that he’d taken the pandemic seriously and it fairly well, calling an unnecessary election during a pandemic made what would be normal power politics (as you say, calling an election at an advantageous time is the norm) came across very badly, and it showed in the election results. I suspect that in retrospect he regrets calling it, though hindsight is 20-20.

@George: OH, I agree, JT probably regrets the call. I think he sold it wrong. He should have pushed a vaccine mandate first and used any opposition as the excuse. Then he’s running because of the pandemic, not in spite of it.

I’m just saying the pundits painting this as a big loss aren’t 100% thinking it through. He lost momentum and maybe his ego got bruised, but tactically, he has gained more time and made everyone afraid of calling any more elections.