Connecticut Supreme Court Declares Death Penalty Unconstitutional

Connecticut eliminated the death penalty several years ago, and now the state's Supreme Court has ruled that the men remaining on death row cannot be executed.

Connecticut’s Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional earlier this week, but the ruling is likely to have far less of an impact than the headlines are making it out to have:

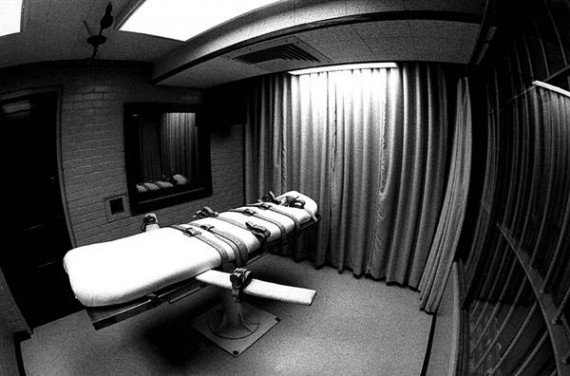

Casting the death penalty as an outdated tool of justice at odds with today’s societal values, Connecticut’s highest court on Thursday spared the lives of 11 men on death row by ruling that capital punishment violated the State Constitution.

The court ruled, 4 to 3, that a 2012 law abolishing capital punishment must be applied to the 11 inmates facing execution for offenses they committed before the measure took effect. But the decision went well beyond the narrow question of whether those men could be executed, declaring that the death penalty, in the modern age, met the definition of cruel and unusual punishment.

“We are persuaded that, following its prospective abolition, this state’s death penalty no longer comports with contemporary standards of decency and no longer serves any legitimate penological purpose,” Justice Richard Palmer of the State Supreme Court wrote for the majority.

In a blistering dissenting opinion, Chief Justice Chase T. Rogers said the majority’s decision overstated the societal aversion to the death penalty, calling the ruling “a house of cards, falling under the slightest breath of scrutiny.”\

Opponents of the death penalty said the decision would quite likely influence high courts in other states, among them Colorado and Washington, where capital punishment has recently been challenged under the theory that society’s mores have evolved, transforming what was once an acceptable step into an unconstitutional punishment.

Though the ruling has no legal impact beyond Connecticut, the United States Supreme Court often uses such opinions as guides to determine whether societal views have shifted, experts on the death penalty said on Thursday. In the past, state court rulings on issues such as the legality of sodomy laws and the execution of mentally disabled people have paved the way for landmark Supreme Court rulings.

“This decision is just one more nail in the coffin of the death penalty,” said Eric M. Freedman, a law professor at Hofstra University who specializes in death penalty cases. “If you have a strong trend in the states rejecting a practice, that influences the Supreme Court.”

Justice Palmer said that the 2012 state law abolishing the death penalty for people convicted of future crimes but permitting the execution of inmates who committed earlier crimes had already marked the “death knell” of a practice long out of step with moral feelings in the Northeast.

The court said it would be “cruel and unusual” to keep anyone on death row in a state that had “determined that the machinery of death is irreparable or, at the least, unbecoming to a civilized modern state.”

The decision went further still, saying the practice was ineffective, rarely imposed and tainted by “racial, ethnic and socio-economic biases.” Death penalty experts said that reasoning could be cited as a precedent in New Mexico, which kept two men on death row after abolishing capital punishment in 2009.

The ruling was seen by legal experts as the inevitable end to an emotional debate over the death penalty for Connecticut, which has executed only one inmate in the last 50 years. Intense political pressure that followed the grisly killing of a woman and her two daughters during a home invasion in 2007 in Cheshire moved the state to keep inmates on death row who had committed crimes before the 2012 law was enacted.

With its decision on Thursday, “the Supreme Court has brought this to its logical conclusion and made it a total abolition,” said Lawrence B. Goodheart, a history professor at the University of Connecticut whose study of the death penalty was cited by Justice Palmer.

The ruling, Professor Goodheart added, validated the political strategy employed by Gov. Dannel P. Malloy, a Democrat who campaigned in 2010 on a platform of abolishing the death penalty but signed a more limited bill amid anger over the Cheshire case.

Given the fact that Connecticut had already abolished the death penalty for future cases and that he it had only executed one person in the last half century, the actual impact of this ruling will actually end up being quite limited. It’s quite unlikely that the any of the eleven people on Connecticut’s death row would have been executed any time soon, if ever. Indeed, the only reason that the 2012 bill that repealed the death penalty did not include provisions covering the men remaining on death row was due to the high-publicized home invasion murder in Cheshire mentioned above. Because of that case, and the public outrage that surrounded, it, there was apparently insufficient public support for any provision that would have dealt with the people on Death Row, which would have been the logical thing to do given the nature of the situation. In most states that have abolished the death penalty legislatively, of course, the bill that’s been passed has included provisions providing that the sentences of those people would be commuted to life in prison without parole, which is what will happen in the wake of this Supreme Court ruling. Because of all that, and because Connecticut was unlikely to execute anyone in the future given the fact that it had outlawed the practice for future cases, the practical impact of this ruling will be fairly limited.

Where the majority on the Connecticut made news, of course, is not in the practical impact of their ruling on the eleven men who were on the Nutmeg State’s Death Row, but their broader statement regarding the death penalty in general. Much like Justices Breyer and Ginsburg did in their dissents to a ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in June, the majority found that capital punishment is per se unconstitutional as “cruel and unusual punishment.” Since the ruling itself only applied state law and the Connecticut Constitution, it has no legal impact outside of the state but it will likely be cited as persuasive authority by death penalty opponents and attorneys defending people sentenced to death in other states. The problem is that, while the argument is one that death penalty opponents will likely cheer, it doesn’t not really seem to have any legitimate legal merit. As I said back in June, the argument that the Eighth Amendment’s bar against “cruel and unusual punishment” and therefore barred by the Constitution in all cases simply doesn’t make sense when you look at the Constitution as a whole. In several places, most prominently in the 5th and 14th Amendments, the Constitution contemplates the possibility that someone will be deprived of their life by the state, but requires that it be done with “due process of law.” Given that, the argument that capital punishment was meant to be included among those forms of “cruel and unusual punishment” barred by the Eighth Amendment simply has no merit. I oppose the death penalty in all circumstances, but the appropriate way to eliminate it is through the legislature, not judicial legerdemain that has no basis in the law.

And make not a dam bit of difference in Texas, Oklahoma, or Missouri.

I oppose the death penalty in all circumstances, but the appropriate way to eliminate it is through the legislature, not judicial legerdemain that has no basis in the law.

Then I suppose you also oppose the ability of the governor to commute a death sentence?

Your rationale makes no sense. The role of the Supreme Court is to interpret the laws that are on the books so that they impact the state’s citizens equally and within the bounds of the state’s constitution. The Supremes in Connecticut were doing exactly what they were supposed to do under the separation of powers.

@OzarkHillbilly: Might make a difference in NM where we have the same situation, death sentence abandoned but still leftovers on death row.

@Mu:

With all due respect, what will be the real world difference in NM, the renaming of death row? 😉

@edmondo: The argument is that ignoring the plain words of the Constitution exceeds the authority of the judiciary.

Do these sort of rulings imply that executions been a mistake all along ? Would the state be legally liable for executions in past history. ?

@James Joyner:

Which constitution? The Constitution of the State of Connecticut presumes in its text that capital punishment may occur, as does the text of the US Constitution, but neither of them either mandates it or specifies the offenses for which it may be applied. The possibility of its existence is presumed, nothing more.

The text of the US Constitution does, however, explicitly debar cruel and unusual punishments, so it seems to me that both documents are saying society, acting through its courts, gets to decide what constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. If the people wish to preserve capital punishment and place it beyond the purview of the courts, they need look no further than the process of amendment – which both documents provide for.