Islam And World War One

The First World War played an intriguing role in the birth of the radical Islam we are dealing with today.

Baylor University History Professor Philip Jenkins makes a provocative argument, namely that the radical Islam that we are familiar with today is yet another of the innumerable consequences of the First World War:

Out of the political ferment immediately following the war came the most significant modern movements within Islam, including the most alarming forms of Islamist extremism. So did the separatism that eventually gave birth to the Islamic state of Pakistan and the heady new currents transforming Iranian Shi’ism. From this mayhem also emerged what would become the Saudi state, dominating the holy places and rooted in strictly traditional notions of faith.

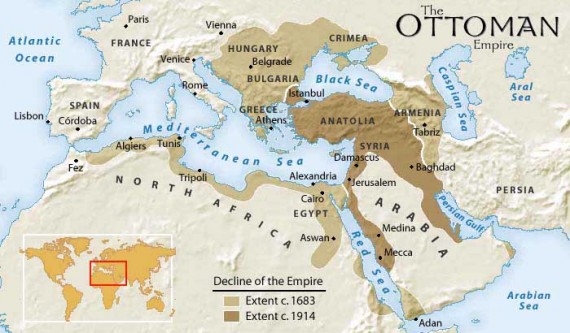

When the war started, the Ottoman Empire was the only remaining Islamic nation that could even loosely claim Great Power status. Its rulers knew, however, that Russia and other European states planned to conquer and partition it. Seizing at a last desperate hope, the Ottomans allied with Germany. When they lost the war in 1918, the Empire dissolved. Crucially, in 1924, the new Turkey abolished the office of the Caliphate, which at that point dated back almost 1,300 years. That marked a trauma that the Islamic world is still fighting to come to terms with.

(…)

Later Muslim movements sought various ways of living in such a puzzling and barren world, and the solutions they found were very diverse: neo-orthodoxy and neo-fundamentalism, liberal modernization and nationalism, charismatic leadership and millenarianism. All modern Islamist movements stem from these debates, and following intense activism, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood was formed in 1928.

One of the founders of modern Islamism was Maulana Mawdudi, who offered a comprehensive vision of a fundamentalist Islam that could confront the modern world. Although Mawdudi was born in 1903, he was already involved in journalism and political activism before the end of the Great War, and by the start of the 1920s he was participating in the fierce controversies then dividing Muslim thinkers in the age of the Khilafat. In 1941, he founded the Jamaat-e-Islami, the ancestor of all the main Islamist movements in Pakistan and South Asia, including the most notorious terrorist groups.

For many Muslims, resurgent religious loyalties trumped national or imperial allegiances. Armed Islamic resistance movements challenged most of the colonial powers in the post-war years, and some of those wars blazed for a decade after the fighting ended on the western front. That wave of armed upsurges would be instantly recognizable to American strategists today, who are so accustomed to the idea of a turbulent Arc of Crisis stretching from North Africa through the Middle East and into Central and Southern Asia.

(…)

One lasting legacy of the Iraqi conflict was the shift of Shi’a religious authority from the city of Najaf. The beneficiary was the emerging intellectual centre of Qom, in Persia, the nursery of generations of later ayatollahs. Although the school’s new heads disdained political activism, they could not fail to see how quickly and easily secular regimes had crumbled over the past decade, leaving clergy as the voices of moral authority and the defenders of ordinary believers. In 1921, the nineteen-year-old Ruhollah Khomeini was already a student at Qom, long before his later elevation to the prestigious rank of ayatollah. Like his counterparts in Egypt and British India, Khomeini grew up seeking a world order founded on a primitive vision of authentically Islamic religious authority.

For Muslims, the Great War changed everything. Modern political leaders look nervously at the power of radical Islam and especially those variants of strict fundamentalism that dream of returning to a pristine Islamic order, with states founded on strict interpretation of Islamic law, shari’a. Terms such as jihadprovoke nightmares in Western political discourse. All these concepts were well known a century ago, but it was the crisis during and immediately following the war that brought them into the modern world.

What we think of today as modern Islam – assertive, self-confident and aggressively sectarian – is the product of the worldwide tumult associated with the Great War. Islam certainly existed in 1900, but the modern Islamic world order was new in 1918.

The Ottoman Empire, of course, was in its final days the modern representation of the great Muslim force that had swept out of Arabia, across the Middle East as far as Egypt, Libya, and Algeria, and northward toward Europe. It’s great conquest was the city of Constantinople, the seat of both what had once been the eastern Roman Empire and Eastern Christianity. Even if World War One had not happened, it’s likely that Ottoman control over the Middle East would have collapsed at some point, and this would especially seem to have been likely once vast oil supplies were discovered in Arabia and the powers that were to be in those areas suddenly began to realize that there could be more advantage to them in being independent than in being vassals of the Sultan. There also likely would have been some kind of nationalism born in this part of the world that would have led to rebellions against Ottoman rule. What would have been less likely, perhaps, is the birth of the radical version of Islam that groups like the Muslim Brotherhood represented, and which we deal with to this day.

As others have pointed out in the past several weeks, World War One also had an impact on the very borders of what we now know to be the Middle East. To a large degree, those borders were determined by the British and French, who had been granted mandates over various parts of the Ottoman Empire’s Middle Eastern territories. Sometimes, the lines they drew made sense, quite often they did not, and to some degree they involved the idea of trying to create a sense of nationalism where one never existed before. In many respects, were are still dealing with the consequences of those decisions in places such as Iraq and Syria.

On a final note, one has to wonder what the idea of a world without a post-war collapsed Ottoman Empire carved up by Europeans would have meant for the State of Israel, or even if there would have been an Israel. Zionism as an idea dates back well before the Great War, of course, at least to Theodore Herzel’s book Der Judenstaat. As a practical matter, though, it was the war and things such as the Balfour Declaration that brought it into the international limelight and, eventually, led to certain promises by the British that some portion of its mandate in Palestine would be set aside as a homeland for the Jewish people. That last part could not have happened without the war, so one has to wonder what would have become of Zionism in a world where Ottoman control over Palestine didn’t collapse all at once, but withered away over time. Perhaps it would have led to the formation of a Jewish state at some earlier point in time, perhaps it might have led to some kind of confederation that would have avoided many of the problems we see today, or perhaps it would have led to wars like we saw in the late 1940s. The other notion, of course, is that if World War One had not led to World War Two and the Holocaust, then the international political pressure to create Israel in 1948 might never have existed at all.

These are all issues we have been dealing with for the past century, and which we are likely to continue dealing with for the foreseeable future. And they all started because a Serbian named Gavrilo Princip killed the heir to the throne of a dying empire.

H/T: Andrew Sullivan

WW I has been called by some historians “The War of the Ottoman Succession.”

This strikes me as history as written by Occidentals. Revisionist Islamic thinking was a process involving many Islamic thinkers and writers, starting long before WWI. A string of innovators built on a history of Islamic thought to create new concepts adapted to new times. Certainly, it was influenced by the relative decline of the Muslim states, but WWI is one of many parts of that. And unless one believes the relative decline of the Muslim states would have reversed itself, its not particularly relevant.

(BTW/ I hate the term “fundamentalist Islam.” These scholars are innovators; they did not go back to basic first principles, but tried to modernize old view.)

The map Doug used illustrates some of my point, but I am not certain it is entirely accurate concerning the Persian Gulf region, where I think Ottoman control had either collapsed completely before WWI or it was in name only.

Man!

The lengths some folks will go to make this seem that it wasn’t Bush’s fault.

;o)

And I really don’t understand what this refers to:

What Iraqi conflict? Long before WWI, Najaf was in Ottoman (Sunni) hands, something that didn’t change with the foundation of Iraq; and the relative importance of Qom versus Najaf was long-disputed, and AFAIK still disputed. Iranians look to Qom, but not all Shi’a are Iranian.

I think you’re exaggerating The Turks had been selling off sections of the vilayet of Beyrout and the department of Jerusalem to Jews for nearly a century before the Empire collapsed in 1922. I don’t think if it had held on for another few years (which is all that is imaginable) it would have impeded the creation of the state of Israel at all.

It’s bizarre to think of it this way but one of the sources of discontent among the Arabs in those Ottoman administrative districts has its roots in Ottoman land law. Very, very little of the land there was owned by Arabs. Most of the landowners were non-Muslims. I wrote a post on that subject some time ago. I may try to dredge up the link. On a related subject you might want to take a look at this comment left at my place on the sources of weak capital formation in the Middle East.

Colonel Lawrence went in there and tried to get those people to work on unity. General Allenby realized, of course, the importance of the location. Leaders there today are focused on the “trees” and not the forest. We now see this ” ISIS” group that wants to establish a new radical, terrorist group is moving in because of a vacuum of capable leadership. Take out the oil equation and none of this would probably even matter. Maybe the British should have stayed there.

Orson Scott Card in one of his sequels to the Ender novels, that has become a movie, talks about a war in the Middle East that involves nuclear weapons. I have always thought that if Iran is really interested in obtaining nuclear weapons it’s not so much to use them against the West or even Israel but a perceived threat from a Sunni Caliphate.

I am reminded of Churchill’s commentary when he was serving, there…

@PD Shaw:

Agreed. The thesis is grossly exaggerated. (Also agree re your point re ‘fundamentalist’ although one has to allow it is too fine a point for most persons).

Without the Ottoman state collapse and the abolishing of the Caliphate, doubtless the structure of the Arab region – Eastern (the Mashreq in Arab terms) – would be rather different, but the author rather typically ignores the Maghreb, which was already on a different path (the Ottomans having either never been acknowledged as Caliphes – Morocco – or long exited by European colonial powers).

The article ignores that Ottoman moderisation had already generated traditionalist Arab backlash – it was on this that Lawrence et al could hang their hats – and questioning of the Turkish nature of the Caliphate then existing. There is no way Ottoman state modernisation could have continued without more reaction (and no way the Ottoman state could have continued without modernisation…), so the idea of the legitimacy of the Ottoman Caliphate (non-Arab as it was) in the Mashreq was already on shaky foundations.

Seems to me the author (i) suffers from Mashreq and Anglosphere goggles, (ii) assumes that post-abolition nostalgia was a fundamental feeling and ignores the anti-Ottoman reaction to the real Ottoman Caliphate (rather than the nostalgia for some ideal idea of the same post-facto); (iii) ignores the sociological change trends that were (are) driving Salafist reaction, with or without a Caliphate.

@Dave Schuler:

Unfortunately Aqoul is no more, which is where your link goes (the old chez moi). I suppose that deserves a comment on blogging at that post….

But It is not that most land was held by non-Muslims, but non-Arabs. Not the same idea.

In any case, under the Ottoman Millet system, the Ottomans were quite comfortable with the Jews, who did not like the Sunni Arabs get all annoying about questioning Law and the like, so long as the Jews did not have allegiances to outside powers. Selling lands to Jews and even having self-ruling Jewish enclaves, so long as such were aligned with Ottoman power, all fine and dandy, no problem under Ottoman ideology. Problem arises when Jewish settlement agencies turn to say British foreign office agents for support.

I believe this link was meant by Dave.

And lets us also not forget that WWI kicked off our now almost banal acceptances of notions of “protecting out interests” as a legitimate rationale for war.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Basra_(1914)

@Dave Schuler: I think you’ll find that while individual Turks and Arabs were selling off land in Palestine, the Ottoman government had outlawed those sales. The Ottomans were under a series of foreign-imposed Capitulations that tied their hands in enforcing their own laws upon foreign citizens.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitulations_of_the_Ottoman_Empire

That would be incomplete and incorrect. Rather more to the point is the screwed up nature of the Ottoman land reform and titling. This is actually a decent discussion re Palestine (by apparently a pacifist Jewish congregation); a quick read over appears to be a reasonably dispassionate discussion.

As in many perverse things governmental, a lot of it boiled down to tax policy and bad tax policy, as well as corrupt implementation of a reform that in theory could have been quite positive….

ETA: perhaps useful to note that among the perverse effects was the dispossession of whole peasant villages where Ottoman notables, wealthy merchants of whatever background and the like registered land in their own name that they historically had not actually controlled or owned under prior legal convention.

As military service (one of course could always buy one’s way out of that…) and taxation was based on the registers, all kinds of perverse incentives arose re peasants versus magnates on registration.