The Cable Bundle is Dying. We’ll Miss it When it’s Gone.

As much as we hate paying $200 a month for television, the future is likely going to be worse.

Bloomberg‘s Gerry Smith examines “Who Killed the Great American Cable-TV Bundle?”

He begins with the obvious:

The reason American consumers are abandoning their cable subscriptions is not a mystery: It’s expensive, and cheaper online alternatives are everywhere.

But argues that it’s more complicated:

But who exactly is responsible for the slow demise of the original way Americans paid for television? That’s a far trickier question. The answer can be traced to a few decisions in recent years that have set the stage for this extraordinarily lucrative and long-lived business model to unravel: licensing reruns to Netflix Inc., shelling out billions for sports rights, introducing slimmer bundles, and failing to promote a Netflix killer called TV Everywhere.

But the next paragraph would indicate that the bundle is still with us:

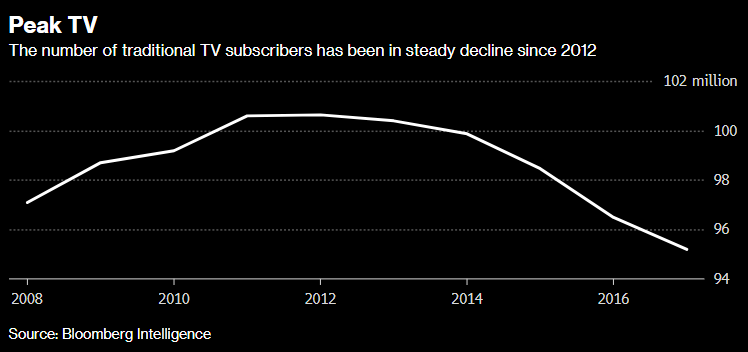

The TV bundle with hundreds of channels, which took off in the 1990s and was ubiquitous in U.S. homes at the start of this century, has fallen from 100 million to 95 million subscribers in the past five years. This quarter, pay-TV giants such as Comcast, Charter, Dish, and AT&T saw an additional 744,000 subscribers disappear.

I’m no mathematician but a five percent decline off peak doesn’t strike me as catastrophic. The accompanying graphic makes it look stark because of scaling choices:

Obviously, it’s not a trend that the industry wants to see. But it’s quite possible that the bulk of those who are willing to live with the inconvenience of non-bundled options have already cut the cord and we’ll see a plateau in the near future.

This steady decline is the driving force behind a series of blockbuster mergers reshaping the media landscape, such as AT&T buying Time Warner, Walt Disney acquiring much of Fox, and Comcast pursuing Sky. Entertainment companies, nervously watching their business model waste away like a slowly melting glacier, are deciding they need to get larger and expand globally to compete with deep-pocketed rivals like Netflix—or sell.

We’ve been seeing mergers in the media sector since deregulation of the industry started four decades ago. Indeed, the pace was much more frenetic in the days when owning a cable or satellite conglomerate was seen as a license to print money.

The TV industry isn’t suffering financially, however, because it keeps raising prices on the remaining customers. The average pay-TV customer today spends $106.20 a month, up 44 percent from 2011, according to Leichtman Research Group. Since 1980 cable, satellite, and phone companies have generated $1.8 trillion in revenue from selling TV service, according to Kagan, a unit of S&P Global Market Intelligence. Revenue last year was $116 billion.

This is perhaps the most amusing part of the trend to me: people are cutting the cord because television bundles are inordinately expensive and the industry is responding by increasing the price of said bundles. It’s a truly bizarre business model but it’s one that seems to be working in the short run.

But many believe a reckoning for the cable bundle has arrived.

“You’ve got high prices, big bundles, and broadband,” said Warren Schlichting, group president of Sling TV, which has more than 2 million people paying for an online service that starts at $25 and offers about 30 channels. “At some stage, the consumer is going to revolt.”

I have plenty of friends in my age cohort, who have been accustomed to the old norm since young adulthood, who are making six-figure incomes, and nonetheless dropping cable or satellite coverage because they (or, more often, their wives) are tired of paying $200 or more a month for television. I’ve certainly considered it but have held on both out of inertia and because I enjoy the convenience of a massive DVR and, especially, easy access to live sporting events.

Smith interviewed dozens of industry professionals and identified numerous culprits.

Perhaps no one deserves more credit for threatening the old TV business model than Netflix Chief Executive Officer Reed Hastings. As the driving force behind the world’s largest streaming video service, with about 130 million subscribers, he’s taught consumers to expect an abundance of old and new shows and movies, without the irritation of commercial interruptions, for just $8 a month.

But if Hastings’s success is responsible for the decline of the cable industry, he had plenty of accomplices among TV executives who fueled Netflix’s rise in the early going. Over the past decade, media companies have licensed their old hits to Hastings, getting a short-term payout but jeopardizing the long-term health of the industry.

I’m a longtime Netflix subscriber and long viewed it as a modest supplement to my DirecTV package. Increasingly, though, it’s a competitor in that I only have so much time to watch programming.

Looking back, some TV executives express regret for doing business with an up-and-coming Netflix, and they struggle to justify their decision to do so. Had they withheld shows from the companies, TV executives might have been vulnerable to lawsuits by the Hollywood talent who have a financial stake in a show being sold to the highest bidder. Netflix frequently offered the most money.

Investors also pressured media companies to take Netflix’s cash. Take, for instance, Time Warner Inc., which is now owned by AT&T Inc. While Disney, CBS, and others licensed many of their old shows to Netflix, Time Warner initially held out. Starting in 2009, Time Warner and Comcast Corp. tried to rally the industry around an idea to slow Netflix by making TV episodes available online—but only to cable subscribers. The idea was called TV Everywhere.

By 2012, however, Time Warner’s investors were demanding to know why the company wasn’t selling its reruns to Netflix, according to one former Time Warner executive. “We sat out for a few years, and all of Wall Street said, ‘What the hell are you guys doing? You’re leaving value on the table for your shareholders!’ ” the former executive said. “So we relented. That was the beginning of the end.”

Time Warner’s Turner Broadcasting did its first deal with Netflix that year. Another transaction the following year brought in more than $250,000 per episode for reruns of shows like Robot Chicken and Aqua Teen Hunger Force, according to the former executive. Time Warner figured Netflix’s money would make up for any lost advertising revenue from viewers who watched on Netflix instead of a cable box.

By 2015, Wall Street had changed its tune. With about 40 million U.S. subscribers, Netflix was becoming a clearer threat. Analysts started pushing media companies to reclaim those old episodes from Netflix to make cable TV more attractive, which could slow the rise of cord-cutting. That year, Todd Juenger, an influential analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co, estimated that big media companies, including Viacom, Fox, and CBS, would have been worth a total $45 billion more if they hadn’t done business with Netflix in the first place.

Again, in my case, the ability to stream previous seasons of shows on Netflix (and, to a much lesser extent, Amazon Prime) was long a mere adjunct to my regular television viewing. In some cases, as with The Wire and Deadwood, I binge-watched shows that I never saw when they were airing after they’d gone off the air. In many other cases, though, including most recently Better Call Saul, I started watching the shows on my DVR as they came out after catching up on previous seasons via Netflix.

We’re likely getting to the point where there’s enough content available via streaming that watching new scripted programming as it comes out is less attractive than it once was. While social media has made it more important than ever for some people to watch the latest episode in real time, that’s a small niche. And I’ve lost the patience not only for watching commercials but even fast-forwarding through them.

Regardless, while hindsight is 20/20, Smith’s article makes it pretty clear that turning down Netflix’s money for reruns was really not an offer executives of publicly-traded companies could refuse.

Smith’s second culprit is arguably both a blessing and a curse:

TV executives have also spent billion of dollars acquiring sports rights, which has driven up the price of TV service—and almost no one has bid more aggressively for sports than Disney CEO Robert Iger. Disney, owner of ESPN, is on the hook for $45 billion in sports rights in the coming years. To cover those fixed costs, ESPN charges TV operators about $8 per month per subscriber, making it the most expensive channel and an easy target for critics.

“ESPN created the model of everybody paying for sports even if only a fraction of the country cares,” said Rich Greenfield, an analyst at BTIG and a Disney critic. “The cost of the bundle has gotten so absurd because of what Disney has done with sports rights.”

Sports programming is still an undeniably huge draw. Justin Connolly, Disney’s executive vice president for affiliate sales and marketing, said ESPN is a big reason why people sign up for new online services such as Sling TV or DirecTV Now. And, of course, access to big-time sporting events is one of the reasons many people renew their cable-TV subscriptions.

For its part, ESPN is happy to avoid a deep inquiry into the connection between sports and rising prices. “We as an industry need to figure out how to avoid the finger-pointing around who is to blame, and provide consumers with the feeling that if they spent $35 or $40 or $90 or $100 on a pay-TV package, they see real value,” Connolly said.

If anyone is responsible for the high cost of sports, it’s not ESPN—it’s sports fans, according to Bill Rasmussen, who co-founded ESPN in the 1970s. “The fan is responsible for ESPN,” said Rasmussen, who no longer works at the network. “They just kept demanding more sports, and ESPN kept going out and buying more rights.”

The nature of the bundle is that everybody pays for some channels they don’t want in order to get all the channels they do. I’m skeptical that the $8 a month for ESPN in a package costing upwards of $100 was the straw that broke the camel’s back even for non-sports fans. Beyond that, the reason companies continue to bid up live sports is because that’s one of a handful of events that consumers feel compelled to watch in real time. Indeed, it’s not only by far the number one driver of my continued willingness to pay the exorbitant cost of the monthly bundle but DirecTV’s exclusive right to NFL Sunday Ticket has been the main thing keeping me a subscriber.

Even the egregious examples aren’t that convincing:

To some executives, no company offers a more egregious example of how the value of sports has spiraled out of control than Time Warner Cable. In 2013 the cable company, now owned by Charter Communications Inc., agreed to pay an average $334 million a year to broadcast Los Angeles Dodgers games for the next 25 years on its cable channel, SportsNet LA. That’s roughly eight times what Fox reportedly paid in the previous Dodgers deal. To cover the cost, Time Warner Cable initially charged almost $5 per month per subscriber, making it one of the most expensive in the bundle.

Five years later, no other major TV provider around Los Angeles carries the Dodgers channel because of the steep price. Unable to watch their favorite team, many Dodgers fans have either switched to Charter, which carries the channel, or else cut the cord. Charter declined to comment.

“That was such an extreme overpayment for sports rights,” one TV executive said of the Dodgers deal. “That’s what’s killing the bundle.”

Granting that Dodgers fans are a relatively small segment of the LA community, it’s hard to believe that the cost of a happy hour beer is really driving away that many consumers in high-cost-of-living area.

The third culprit, though, is more persuasive:

The cable bundle was badly wounded by a man who made one of the great fortunes from it: Dish Network Corp. co-founder Charlie Ergen.

[…]

The cable industry argued prices would rise if consumers could choose only certain channels, and channels aimed at minority groups, for instance, wouldn’t survive without every subscriber paying for them—regardless of whether they watched.

It wasn’t until 2015, when Ergen introduced Sling TV, that the floodgates truly opened. Sling TV is a so-called “skinny bundle,” giving online subscribers the option to buy just a few channels and pay a much lower monthly fee—in this case, about a fourth of the average cable bill. Since its arrival, at least six more online TV services have entered the market.

These lower-cost services have won back some people who quit cable, providing hope for the likes of ESPN or CNN, whose channels are included. But the skinny bundles haven’t won back all the departed. They have only about 6 million customers so far. And companies whose channels have been excluded from them have little recourse to make up lost ground.

“Sling TV was a watershed moment,” said Moffett, the analyst. “It broke the all-for-one and one-for-all model for the first time.”

Again, my math skills aren’t the best but, if the industry has lost five million subscribers over the last five years and Sling has picked up six million subscribers, then they alone have done more than “won back all the departed,” what with six million being more than five. While ESPN and company doubtless contributed to the desire for cord-cutting by jacking up prices and Netflix helped make it attractive by providing lots of quality content, Sling is able to provide content theretofore available only in a cable or satellite bundle: live access to local and national news, the current season’s programming on key networks, and some modicum of live sports.

Smith’s last culprit is rather odd:

In hindsight, some TV executives believe the industry would be much healthier now if everyone—programmers and distributors—had agreed to make all episodes of shows available to cable subscribers on any device. That was the dream behind TV Everywhere, an idea hatched in 2009 by Comcast CEO Brian Roberts and Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes. But in those crucial early days, TV Everywhere struggled to get off the ground.

Executives couldn’t agree on how long to make old episodes available for subscribers. Some gave viewers only a day to catch up on a show they missed because the broadcasters had sold the reruns to another service. Others made past series available to subscribers for a month. Consumers became confused about where to go and how long they had to binge-watch a show. Some TV networks were slow to make their channels available online.

In the end, the cable industry’s failure to protect the bundle came down largely to greed, Moffett said. Media executives wanted to charge more for certain rights, like making every old episode available to cable subscribers, or granting the rights to watch a show on an iPad outside the home, instead of giving them away for the good of the industry.

While there were certainly advocates for universal availability back in 2009, it’s hindsight bias in the extreme to argue that it was the obvious choice. Programmers and distributors alike had real concerns about their intellectual property rights. They were making serious money selling DVDs of past seasons; of course they weren’t going to simply give them away for free. Additionally, figuring out how to make the advertising model that the industry was built on work for on-demand content was naturally going to take time. And, of course, Netflix and other bidders for rights to license older programming naturally wanted exclusive rights.

It’s true, though, that the post-bundle world looks to be much worse in some ways. While consumers have won the right to chose which content to pay for, with the ability to pay much less if one only wants a relative handful of content, those who want a wide array of content may well wind up paying more money for less convenience.

That Netflix, Amazon Prime, and others are producing high-quality content exclusively for their customers is great insofar as more high-quality content is valuable. But it means that consumers no longer have all the programming they want available for a set price from a single device. They have to buy it à la carte and remember on which device they need to view it. Currently, I watch most of my programming via my DirecTV interface and view Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Bluray content via my Sony Bluray device. (I can also view the two streaming services via my smart TV but doing so is actually less convenient than doing so through the Bluray, since I have everything wired through a surround sound audio receiver.) That’s not all that complicated but the trends are moving toward it becoming much more so.

Disney, for example, is poised to take back all of its content—including not only Disney and Pixar movies but all of the Star Wars and Marvel Comics Universe content—and show it only on its soon-to-launch streaming service. CBS last year launched a new Star Trek series available only via its streaming service. One presumes other networks will follow suit.

The industry will certainly kill off the bundling system once the bundle ceases having the lion’s share of desirable content. By all indications, though, it’ll be more expensive and less convenient than the bundle was.

UPDATE: Commenter @inhumans99 indirectly points to another issue I missed in the original post:

If you want to watch Castle Rock you have to have Hulu (or use Sprint to get it free w/limited commercials, like myself), if you enjoy Stranger Things, OITB, or other hot and trending Netflix originals you have to pay for well…Netflix, if you are a Trekkie (thank goodness I am not) you now have to pay for CBS All Access, if you enjoy Star Wars, the Marvel Universe films, and lots of other Disney content including original films soon you will have to pay for Disney’s streaming service.

Because of cross-ownership of content production, broadcast, Internet, and cellular companies we may well be headed to a point where some content is only open to those with particular phones (Android vs. iPhone) or cellular providers (Sprint vs. Verizon vs. AT&T). Right now, as @inhumans99 notes, Hulu and Sprint have a partnership. AT&T owns DirecTV and offers free streaming of DirecTV on their network. What happens when DirecTV gets into the content-production business like Netflix and Amazon?

Trust me, life will get better. I haven’t had cable since 2001 and I don’t miss it a bit (except for baseball).

You can get all the TV networks you want at a much lower cost than cable or satellite. Take a look at the website suppose.tv. You enter the channels you watch and it compares all the TV service options, showing the best one for your family.

I was just discussing this yesterday in a Facebook comment thread.

While I love streaming services such as Neflix, Amazon, and Hulu, the idea of having to subscribe to a bunch of different services to get programming I want to watch seems like something that could end up being annoying and, eventually, as expensive as current cable bills. This is especially true given the fact that much of the “cost savings” that I see calculated from all this leaves out the fact that you need Internet access to use any of them.

We’ve cut the cord. The only thing I really miss is sports, particularly baseball. I don’t miss having to organize my viewing of the rest of it around the network schedule. That often doesn’t work for me.

I know a number of people who have even less interest in sports than I do. They also would like to watch stuff on SyFy, but they can’t because the local cable monopoly doesn’t carry it. I don’t miss cable, I don’t miss bundling. Neither do they.

Fragmentation will be a thing, though. It will probably get worse before it gets better, too. But it will get better.

@Jay L Gischer: With the exception of sports–and sometimes not even then—I watch essentially nothing live anymore. My DVR houses my shows. Hell, I literally don’t know when they come on and, often, what network airs them.

@Doug Mataconis: I’m about at the point of dumping my internet service at home and putting myself on an internet diet. First, it’s ridiculously expensive, and second, I’m getting fed up with the constant pestering from AT&T to bundle my internet service with my TV. I don’t have a TV, have never had a TV, and don’t want a TV!

I am paying close to $180 a month. I seldom watch TV and when I do it is less than ten channels. Why am I doing that?

For the first time in years I broke down and watched some golf on Sunday. I was pleasantly surprised that there was some real action – four or five guys were within two strokes of each other.

@Tyrell: I watched a bit of the British Open and yesterday’s PGA because Tiger was in contention. And that’s the value of the bundle: the ability to watch instantaneously when something happens serendipitously like that. For a regular season football game, I can plan to go to a sports bar or a friend’s house. But it’s nice to be able to just turn on the TV when you want to see something.

@Doug Mataconis:

I wonder how long it will be before a company offers bundles of various on-demand online services.

@Doug Mataconis:

This should be a golden age for folks who have been saying it would be the second coming of wonder bread if they could only pay for the content they want to watch instead of paying for everything. Oftentimes this individual was griping about cable tv costs back in the day thinking that if their cable provider did not have to help pay for PBS/NPR type programming or shows like Sesame Street it would be so much cheaper.

My rebuttal was hey, if I have to pay for sports that I do not watch then I am fine with the cable guys throwing some (of my) money in the till to keep PBS, etc., afloat.

The reality is that these complainers are getting their wishes granted but finding that unless they only care about sports, or a small handful of shows on cable that paying for all the parts to watch all the content they want to enjoy is almost as expensive as the whole package (such as a high-end cable bundle like Xfinity triple play w/premium channels included in the bundle, yeah…used as an example because that is what I have).

If you want to watch Castle Rock you have to have Hulu (or use Sprint to get it free w/limited commercials, like myself), if you enjoy Stranger Things, OITB, or other hot and trending Netflix originals you have to pay for well…Netflix, if you are a Trekkie (thank goodness I am not) you now have to pay for CBS All Access, if you enjoy Star Wars, the Marvel Universe films, and lots of other Disney content including original films soon you will have to pay for Disney’s streaming service.

You also now have to deal with more apps to click on when using a tivo, apple tv 4k, smart tv, blu ray, Roku, Amazon Fire, ipad, or phone to watch, so while it is a minor inconvenience it is still another degradation of your quality of life.

I could have made this post really short and to the point by just telling folks they should have been more careful for what they wished for.

@inhumans99: or you can just rotate through the streaming services.

Do I want to watch Stranger Things, Marvel things, Westworld and the Handmaids Tale? Yes, but I don’t want to watch them all at the same time — I don’t have time for that.

Pick one service, watch until you start getting bored, stop that service and start the next.

@Doug Mataconis: The assumption is that you already have internet at sufficient speeds so the additional cost of that segment of the service bundle is zero. Is that not your situation, or is your internet cost reduced because of a cable bundle to which you subscribe?

@inhumans99: Actually, the “golden age” for me was when I had a townhouse and our owner’s association negotiated a $10/mo cable contract for wiring 32 households together on one contract. (I would have paid off my 30 year mortgage 3 years ago, FYI) Still in all, because of the way that I watch TV, Roku (one time $49) with Hulu at $7/mo and CBS All Access at $8 gives me all the TV I can watch in the 2 or 3 hours in a typical day that I watch TV. YMMV, though, as I am single, no kids, watch sports but don’t care what I am watching–live or on delay (Pluto Network has … unique… sports channels). Beyond that, since I use TV mostly as mental junk food, I’m probably the Platonic Ideal cable cutter.

1-) The TV bundle was good for people that liked to watch a lot of TV, not people that liked good television. It always had poor offerings for niche content. And there is the problem of the time wasted watching commercials.

2-) Decline in TV ad rates was going to make TV more expensive, and that was inevitable even if Netflix did not exist.

3-) Torrents meant that streaming was inevitable.

@Doug Mataconis: I looked up my budget from two years’ ago, before we cut cable. We were paying about $230 a month for Comcast. Now we are paying $104 a month: $79 for Internet service through Comcast, $12 for Netflix, and $13 for Hulu. The savings are well worth it.

@OzarkHillbilly:

Never bothered w/cable and resigned myself a long time ago that I’d need to swing by the local once a week to catch the Red Sox or Celts. I’d be very happy if the MLB and NBA streaming packages did away with blacking out the home team, even if at an extra charge. A couple of times a month we’ll buy a movie off Amazon, Google Play or iTunes, sometimes for a cheap as $3 and my wife likes borrowing DVD’s from the library.

“While consumers have won the right to chose which content to pay for, with the ability to pay much less if one only wants a relative handful of content, those who want a wide array of content may well wind up paying more money for less convenience.

“ESPN created the model of everybody paying for sports even if only a fraction of the country cares,” said Rich Greenfield, an analyst at BTIG and a Disney critic. “The cost of the bundle has gotten so absurd because of what Disney has done with sports rights.”

“The cable industry argued prices would rise if consumers could choose only certain channels, and channels aimed at minority groups, for instance, wouldn’t survive without every subscriber paying for them—regardless of whether they watched.”

Bout TIME everyone pays their OWN way! Bout time the general public stops having to subsidize the SPECIAL people!

@Monala: I see you went for one of the “enhanced billing” (note to thread: yes, that’s what Hulu actually calls it’s service upgrades) options. What do you have that’s different from basic and how do you like it?

$200 a month? You’re doing it wrong.

DirecTV – $57.09 (after negotiation)

Cell for two people – $100.72 (including new S9 and unlimited plan for two)

Internet – $30.83

So, still under $200 for a triple play from three different companies.

While we have Amazon Prime, we torrent like crazy. Everything is out there.

I’m paying for Netflix, HBO Now, and Amazon Prime. Most of my viewing time is spent on the first two. Amazon Prime video is worth it only because it comes with other goodies (shipping, etc.). I use a Roku box.

But really, that’s the limit of what I’m willing to spend on TV. I love the Marvel films but there’s no way I’m going to subscribe to a Disney channel just to watch them. The other important factor is time. I just don’t have enough time in the day to watch everything out there.

Maybe this situation will be much more irritating in the future, but currently it all works out well for me & my viewing habits.

My streaming device is a Roku, and I’m typically subscribed to a single major internet service at a time (Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, Showtime, HBO, Starz, Crunchyroll, etc). After a few months with one, when I start to run out of content I’m really interested in watching, I’ll either switch to one I haven’t been subscribed to in a while or I’ll go with one that’s sent a free month re-subscription offer. Many months later, when I finally get back around to the service I had at the start there’s always a bunch of new seasons of content I’m interested in waiting for me.

@Paine: I watch Marvel and DC movies on my yearly trip to Korea. From one perspective, a thousand seems like a lot to spend to watch 4 or 5 movies, but I’m not taking the trip to watch the movies, so I call them free. I expect that I will eventually need to actually subscribe to some service or another if I want to watch them, but so far, I’ve really been grateful that I didn’t “spend any money” watching them, so maybe I’ll bag it at some point. The only good one on the last trip was Wonder Woman, and I only gave it a B+.

DirectTV already has content production. Their channel is the Audience Network. I’m not sure what they are pushing now, but they had a pretty good TV show called Kingdom, and a decent one called Mr. Mercedes (based on a Stephen King trilogy).

Welcome to peak TV, where there are dozens of quality shows on, (some of which have already come and gone) that you’ve never even heard of.

We still have cable TV for now, but only because of baseball. I’m thinking I’ll give it another year and then reevaluate.

@Andre Kenji de Sousa:

I sorta disagree with the dynamic.

People always had to pay a lot for good television. You couldn’t have HBO without having cable. The average person was content with average popcorn fare on broadcast channels and not paying an extra 30 dollars a month for great television.

Then Netflix comes along and makes great content more accessible to the masses. Now your basic cable package seems wildly overpriced and underwhelming when you finally discover shows like Breaking Bad (look at that shows rating before and after it was picked up by Netflix) or older HBO shows on these streaming services. The average person still watches trash for television, it’s just that now there is less gatekeeping to finding great content. But the reality is, I could name about 2 dozen cable TV shows that are incredible, and that’s something that would exist with or without steaming services. As far as content production goes, the streaming services are still well behind the cable channels. FX by itself probably has more great television than Netflix. FX and HBO combined have more great television than all the streaming services.

The main difference in my view though is that great television/peak TV essentially exists because of the modern TV bundle. HBO, Starz, Showtime, Cinemax, FX, and AMC all have at least 2 new shows a year that are emmy quality great television and are all wildly different. To say nothing of every other network’s wannabe prestige shows that pop up. Even the History Channel has shows like Vikings. Until the streaming services prove they can create great original content at the rate of cable, the decline of cable television will directly lead to a decline in quality programming.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: It allows you to stream on multiple devices at the same time. That helps when my husband, my daughter, and I all want to watch different things at the same time. 😉

@Console:

People were complaining that cable bundles were expensive, that there was too much programming in repetition, that there were excessive commercials, for a long, long time. That was happening before Reed Hastings decided to create an online service to rent DVDs. It was always terrible for niche programming(Not for TV series like Walking Dead, but for things like documentaries, journalism, art movies and anything that does not have English as original language). Very few bundles offer BBC World News in the United States, you only have access to British TV shows like Newsnight or Mock the Week if you resort to piracy.

And expensive Ad rates were an important part of the equation, and that would end, regardless of Netflix.