Trump the Supreme Loser

He appointed a third of the Justices but has the worst record before them in modern history.

A NYT report by Adam Liptak (“New Trump Cases Shadowed by Rocky Relationship With Supreme Court“) highlights the 45th President’s losing record in the nation’s highest court.

“I’m not happy with the Supreme Court,” President Donald J. Trump said on Jan. 6, 2021. “They love to rule against me.”

His assessment of the court, in a speech delivered outside the White House urging his supporters to march on the Capitol, had a substantial element of truth in it.

Other parts of the speech were laced with fury and lies, and the Colorado Supreme Court cited some of those passages on Tuesday as evidence that Mr. Trump has engaged in insurrection and was ineligible to hold office again.

But Mr. Trump’s reflections on the U.S. Supreme Court in the speech, freighted with grievance and accusations of disloyalty, captured not only his perspective but also an inescapable reality. A fundamentally conservative court, with a six-justice majority of Republican appointees that includes three named by Mr. Trump himself, has not been particularly receptive to his arguments.

Indeed, the Trump administration had the worst Supreme Court record of any since at least the Roosevelt administration, according to data developed by Lee Epstein and Rebecca L. Brown, law professors at the University of Southern California, for an article in Presidential Studies Quarterly.

“Whether Trump’s poor performance speaks to the court’s view of him and his administration or to the justices’ increasing willingness to check executive authority, we can’t say,” the two professors wrote in an email. “Either way, though, the data suggest a bumpy road for Trump in cases implicating presidential power.”

That Trump expected “his” Justices to show loyalty to him isn’t shocking. He has a toddler’s understanding of how government works. But the fact that he’s lost so much is likely a surprise to most observers of American politics, especially in the current hyper-polarized political environment.

Now another series of Trump cases are at the court or on its threshold: one on whether he enjoys absolute immunity from prosecution, another on the viability of a central charge in the federal election-interference case and the third, from Colorado, on whether he was barred from another term under the 14th Amendment.

The cases pose distinct legal questions, but earlier decisions suggest they could divide the court’s conservative wing along a surprising fault line: Mr. Trump’s appointees have been less likely to vote for him in some politically charged cases than Justice Clarence Thomas, who was appointed by the first President Bush, and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., who was appointed by the second one.

In his speech at the Ellipse on Jan. 6, Mr. Trump spoke ruefully about his three appointees: Justices Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, suggesting that they had betrayed him to establish their independence.

“I picked three people,” he said. “I fought like hell for them.”

Mr. Trump said his nominees had abandoned him, blaming his losses on the justices’ eagerness to participate in Washington social life and to assert their independence from the charge that “they’re my puppets.”

He added: “And now the only way they can get out of that because they hate that it’s not good in the social circuit. And the only way they get out is to rule against Trump. So let’s rule against Trump. And they do that.”

Mr. Trump has criticized Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. on similar grounds. When the chief justice cast the decisive vote to save the Affordable Care Act in 2012, Mr. Trump wrote on Twitter that “I guess @JusticeRoberts wanted to be a part of Georgetown society more than anyone knew,” citing a fake handle. During his presidential campaign, Mr. Trump called the chief justice “an absolute disaster.”

Again, this is the reaction of a toddler. But it’s also a longstanding whine when Republican-appointed Justices rule in ways their co-partisans dislike. And, indeed, there’s surely a wee bit of truth to it: living in DC and being part of a distinct social circle likely has at least a subtle impact on the worldview of the Justices. (That’s to say nothing of rich benefactors, but that’s a subject of other posts.)

When he spoke on Jan. 6, Mr. Trump was probably thinking of the stinging loss the Supreme Court had just handed him weeks before, rejecting a lawsuit by Texas that had asked the court to throw out the election results in four battleground states.

Before the ruling, Mr. Trump said he expected to prevail in the Supreme Court, after rushing Justice Barrett onto the court in October 2020 in part in the hope that she would vote in Mr. Trump’s favor in election disputes.

“I think this will end up in the Supreme Court,” Mr. Trump said of the election a few days after Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death that September. “And I think it’s very important that we have nine justices.”

After the ruling, Mr. Trump weighed in on Twitter. “The Supreme Court really let us down,” he said. “No Wisdom, No Courage!”

The ruling in the Texas case was not quite unanimous. Justice Alito, joined by Justice Thomas, issued a brief statement on a technical point.

Those same two justices were the only dissenters in a pair of cases in 2020 on access to Mr. Trump’s tax and business records, which had been sought by a New York prosecutor and a House committee.

To the extent Justices are going to favor the interests of their political party or show loyalty to the President who appointed them (more on that later), they’re going to do it at the margins. Too many of the Trump cases were simply slam dunks.

The general trend continued after Mr. Trump left office. In 2022, the court refused to block the release of White House records concerning the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, effectively rejecting Mr. Trump’s claim of executive privilege. The court’s order let stand an appeals court ruling that Mr. Trump’s desire to maintain the confidentiality of internal White House communications was outweighed by the need for a full accounting of the attack and the disruption of the certification of the 2020 electoral count.

Only Justice Thomas noted a dissent. His participation in the case, despite his wife Virginia Thomas’s own efforts to overturn the election, drew harsh criticism.

Less of a slam dunk but, still, a relatively easy decision.

Mr. Trump’s rocky record at the court offers only hints about how the justices will approach the cases already before them and on the horizon. His claim of absolute immunity appears vulnerable, based on other decisions from the court on the scope of presidential power.

The case examining one of the federal statutes relied on by the special counsel in the federal election-interference case, which makes it a crime to corruptly obstruct an official proceeding, does not directly involve Mr. Trump, though the court’s ruling could undermine two of the charges against him.

The justices have been skeptical of broad interpretations of federal criminal laws, and the arguments in the case will doubtless involve close parsing of the statute’s text.

I don’t have a strong prediction on this one.

The case that is hardest to assess is the one from Colorado, involving as it does a host of novel questions about the meaning of an almost entirely untested clause of the 14th Amendment, one that could bar Mr. Trump from the presidency. The case is not yet at the Supreme Court, but it is almost certain to arrive in the coming days.

Guy-Uriel E. Charles, a law professor at Harvard, said the justices would have to act.

“The Supreme Court is a contested entity, but it is the only institution that can weigh in and try to address this problem, which needs a national resolution,” he said. “There has been some loss of faith in the court, but even people who are deeply antagonistic to it believe it needs to step in.”

While this is an incredibly novel case, posing all manner of untested legal questions, my strong sense is that Trump will win this one. There are just too many ways for the Justices to rule in his favor and, indeed, while I think Trump fomented an insurrection I think he ought to remain eligible to appear on the ballot until and unless he’s convicted of the crime.

The Epstein and Brown article cited by Liptak is currently Open Access, meaning it’s not behind a paywall. It’s titled “Is the US Supreme Court a reliable backstop for an overreaching US president? Maybe, but is an overreaching (partisan) court worse?”

The Abstract:

The Roberts Court has been called the most “___” Court in history, with many different adjectives being offered. Surprisingly, our study of voting data from Supreme Court terms 1937–2021 shows that the Roberts Court is the most “anti-president” Court in that period: It has ruled against the president at a greater rate than any other Court. Should we take this to mean that the Court will be there to protect democracy if an overreaching president tries to trample constitutional limits? Not necessarily. Additional analysis and a deep dive into the cases and reasoning reveal a more complicated picture, of a Court exhibiting historic levels of partisan and loyalty bias as well as a strong penchant for judicial supremacy.

Offhand, my hypotheses would be 1) “This is explained by ideology. Conservative justices are inherently going to be more skeptical of broad claims of power beyond what’s in the black letter Constitution.” and 2) “This is explained by Presidential overreach. For a variety of reasons, the Presidents in question—George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump—were more prone to overreach than their recent predecessors.” These are not, of course, mutually exclusive.

Epstein and Brown offer a more complex explanation. And, alas, not one favorable to the Roberts Court.

Our systematic analysis of voting data and doctrine since the 1937 term suggests that the Court has often served as a reliable backstop. Although it tends to hold for the president across all cases (a 65% win rate), in highly important disputes implicating executive authority, the justices are far less deferential. In these weighty cases, the Roberts Court (2005–2021 terms) was especially tough on the president, ruling in his favor in only 35% of them.

These results might be understood to suggest that democracy is in safe hands. The Court under Chief Justice John Roberts, in particular, seems more than willing to act to constrain power-grabbing presidents. But “seems” is the operative word. Two findings must temper any conclusion that the Roberts justices are likely to be a reliable check on an overreaching president. First, the data show that the Roberts justices are especially and uniquely willing to put the brakes on a president who does not share their partisan affiliation, while far less likely to check a president of the same party, especially if the president appointed the justice (the “loyalty bias”). These results, we suggest, sit comfortably with intensifying affective polarization—the “tendency to dislike and distrust those from the opposing party” among Americans (Druckman et al., 2021, p. 28)—the justices not excepted (Das et al., 2013; Devins & Baum, 2017).

Second, looking more granularly at the way that courts have acted either to invalidate or to uphold presidential actions over time, we find that the Roberts Court has consistently done so in a way that injects itself more directly in matters of policy across the spectrum of legal issues than prior courts. It has provided indications that it views its role as imposing substantive agendas through its interpretations of the powers of the other branches. Again, this finding is compatible with the larger political environment in which the Court operates: What with increasing polarization and the resulting gridlock, the elected branches may lack the wherewithal to retaliate against even extreme judicial overreaching—likely enhancing the justices’ self-confidence (Epstein & Posner, 2018; Hasen, 2013). Seen in this way, characterizing the Court as “imperial,” as one scholar has, seems apt (Lemley, 2022; see also Liptak, 2022).

Putting together the existing commentary and the results of our quantified data and doctrinal analyses leads us to ask whether the branch that was thought to have “no influence over either the sword or the purse” (Hamilton, Federalist No. 78) is, in fact, transforming itself into the branch with the greatest ultimate control over matters of national policy, all without benefit of democratic selection or accountability.

Yikes.

The methodology is a bit complex for a blog post. But it’s thorough. They constructed a “’presidential power’ data set. It consists of 3,660 cases (31,401 votes cast by 48 justices)—or 42% of all orally argued cases decided between the 1937 and 2021 terms.”

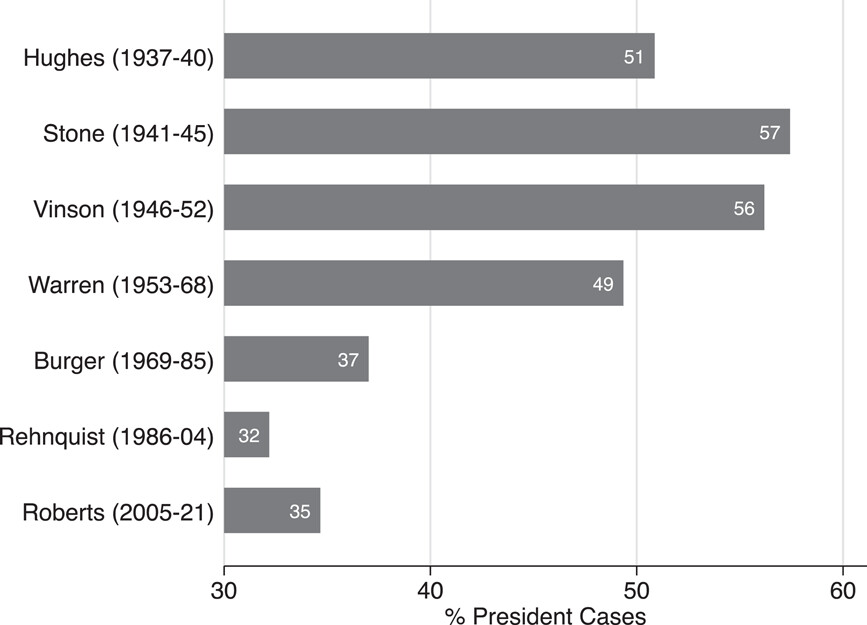

This figure tends to lead credence to both of my hypotheses:

The most recent courts have decided a significantly smaller percentage of cases in favor of the President, with the two led by staunchly conservative Justices doing so less often. Yet this is also the period of the so-called Imperial Presidency.

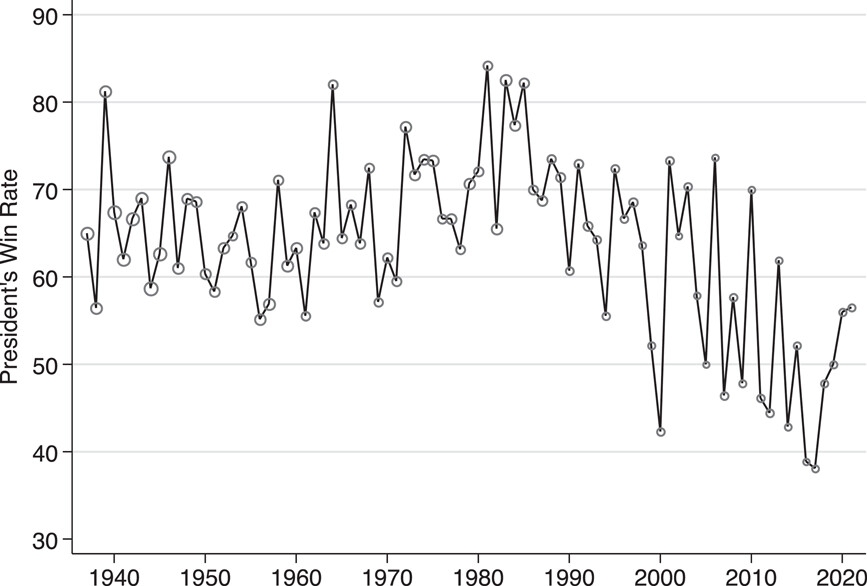

This figure provides a different perspective on the same data:

As the authors note, “Overall, across the 85 terms in our data set, the rate is 65%” but “that percentage masks some term-by-term variation—from a high of 84% during the 1981 term (Ronald Reagan’s first year in office) to a low of 38% in 2017 (Donald Trump’s first year).”

Scholarly explanation for this is, as you’d imagine, conflicted.

The decline in support for the president has not gone unremarked (e.g., Liptak, 2017). The commentary, though, tends to center on presidents rather than on Court eras—noting, for example, that since the Reagan administration, “each succeeding president did worse than the last” (Liptak, 2017; see also Epstein & Posner, 2018). Depicting support by the chief justice, as we do in Figure 3, suggests another possibility: The decline in the win rate traces to the Roberts Court—not to any trend toward less deference.

Either way, some scholars attribute the decline in presidential win rates to the contemporary Court’s disdain for the administrative state rather than to its mistrust of presidential power (Chemerinsky, 2019; Herz, 2015). Metzger (2020, p. 2) explains it this way: “[C]onservative groups have put sustained efforts into fostering academic attacks on core features of administrative government. … And … the Trump administration [selected] judges who are receptive to these conservative attacks.” Those judges include Trump appointees Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and likely Barrett, who join Thomas and Alito as “strident administrative skeptics” (Metzger, 2020, p. 3).

This skepticism has manifested itself in several important doctrinal shifts related to the administrative state.7 Most relevant here is the widespread belief that the deference accorded to executive branch interpretations of statutes by Chevron v. NRDC (1984) has reached zombie status, dead but still not interred (Herz, 2015; Howe, 2022; Pierce, 2022). In the 2021 term, for example, the Court decided two cases in which Chevron theoretically should have been applied to resolve the issue, but the Court ignored it (American Hospital, Becerra v. Empire Health). Despite Chevron‘s having established that courts must give deference to reasonable agency interpretations of an ambiguous statute, in both cases, the Court assessed the agency’s regulation based on its own interpretation of the statute, not considering or citing Chevron, either when upholding the agency rule or when overturning it.

Considering the Chevron retreat, it seems possible that the Roberts Court’s less deferential posture reflects its “antiadministrativism” and not disdain for presidential power more generally (Metzger, 2020). If so, this might temper any conclusions about the Court’s willingness to check an overreaching president, as opposed to overreaching agencies.

But, of course, both the tenure of a given Chief Justice or a given President are imperfect units of analysis. The composition of the Court can change rather wildly during either period. Indeed, Clarence Thomas is the only member of “the Roberts Court” other than Roberts himself who has served the entirety of that era. Every President during the post-1941 period in the study, save Jimmy Carter, appointed at least one Justice. Franklin Roosevelt served long enough to appoint nine! Dwight Eisenhower had five appointees. Harry Truman, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan had four each.

Regardless, the authors conclude:

The title of our article poses two questions. The answer to the first—Is the US Supreme Court a reliable backstop for an overreaching US president?—is a qualified yes. Although the Court has ruled more often for the president than not, the justices have been far less willing to rubber-stamp presidential claims of authority in the disputes that matter most. Especially iconic examples include Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer (1952) and United States v. Nixon (1974).

The qualification to this answer stems from the behavior of the Roberts Court. On the one hand, it fits this pattern. Actually, it is significantly less willing to bend to the president than all other chief justice eras since at least 1937. On the other hand, the Roberts Court is hardly a reliable backstop. The justices are uniquely partisan, more frequently voting for presidents who share their party identity—especially if the president appointed them. And looking beyond the bare win rates, there is little indication that the Roberts Court’s willingness to rule against the president bears any reliable relation to preserving the balance among the branches or the workings and accountability of the democratic process (Bernstein & Glen, 2023; Driesen, 2022). Instead, there are increasingly frequent indications that the Court is establishing a position of judicial supremacy over the president and Congress. As we noted earlier, an iconic quotation from the foundational case of Marbury v. Madison has often been seen as a harbinger of judicial supremacy: “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial branch to say what the law is.” Considering our findings, it is perhaps not surprising that over half of the total number of majority or concurring opinions in Supreme Court history to have quoted this language from Marbury have been penned by the Roberts Court.34

This takes us to the second question posed in our title: Is an overreaching (partisan) Court worse than an overreaching president? Although we are not sure of the answer, we think asking the question is important if only because the Court is so often thought to be the hero in narratives of overreaching presidents: Think United States v. Nixon. This decision is widely viewed as an act of judicial supremacy (and, fittingly, includes the famous “emphatically” language from Marbury), but in that situation widespread, bipartisan agreement existed that a national crisis needed to be averted, that the rule of law was in jeopardy and needed to be saved.35 There was no sense that what the Court did in Nixon was business as usual. But the Roberts Court provides cause for caution because its willingness to check political actors across the board has become intricately intertwined with a tendency to aggrandize the judicial role in all areas of political action. While the presence of an active judiciary can be a salutary feature in a vigorous three-branch structure,36 that is less true if the Court is routinely willing to disregard traditional limits on judicial authority, such as appropriate deference to political decision making and respect for precedent. Indeed, the question hovers: whether the Court may be eyeing Lady Justice’s scale less as a humbling aspiration for its work than as an alluring receptacle for its confident thumb.

So, the irony may be that the Roberts Court saves us from the excesses of Trump, not so much out of respect for the rule of law but to assert its own dominance in the system.

Very interesting, James. Thanks for this.

Very interesting and thank you for this kind of content. Seems worthwhile to make the point that growing obstruction in Congress has put Presidents in the position of doing stuff without legislation, making court cases more likely.

That’s pretty much all that’s going on here. In other cases, there seems to have been a strong element of the Court signaling, “We want to rule for conservatives. But you can’t just throw a crappy case at the docket and leave all the work to us. Help us out, bring a decent case and make a decent argument.”

Also, they are not Trump’s judges. They are Leonard Leo’s, and by extension, Chuckles Koch’s judges. An arrangement enforced by the Harlan Crow types including whoever it was that threw the bus under Clarence Thomas. Alito, Thomas, and Roberts were founders of the Federalist Society. Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett are pretty much tank grown products of the FS.

NYT has an appalling “guest essay” today by one Samuel Moyn, a law professor. Making no legal argument at all, he says the liberal justices should make the decision to overturn the CO Supreme Court unanimous so as to preserve respect for the Court. (Is there no obligation on the Court to behave respectably?)

@gVOR10:

Ha. The liberal justices cannot “preserve” that which no longer exists. Public opinion of the court was destroyed by its rightwing Federalist Society hacks imposing their partisan and papist views on the country — despite precedent, prudence, and their own promises.