What Citizens United Changed: Not Much

While the Supreme Court's decision in Citizens United has been blamed for the massive increase in money in this year's campaign, it really wasn't the culprit.

While the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United has been blamed for the massive increase in money in this year’s campaign, it really wasn’t the culprit.

Matt Bai, NYT Magazine (“How Much Has Citizens United Changed the Political Game?“):

It helps first to understand what Citizens United did and didn’t do to change the opaque rules governing outside money. Go back to, say, 2007, and pretend you’re a conservative donor. At this moment, you would still have been free to write a check for any amount to a 527 — so named because of the shadowy provision in the tax code that made such groups legal. (America Coming Together and the infamous Swift Boat Veterans for Truth were both 527s.) Even corporations, though they couldn’t contribute to a candidate or a party, were free to write unlimited checks to something called a social-welfare group, whose principal purpose, ostensibly, is issue advocacy rather than political activity. The anti-tax Club for Growth, for instance, is a social-welfare group. So, remarkably, is the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity and Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS.

There were, however, a few caveats when it came to the way these groups could spend their money. Neither a 527 nor a social-welfare group could engage in “express advocacy” — that is, overtly making the case for one candidate over another. Nor could they use corporate money for “electioneering communications” — a category defined as radio or television advertising that even mentions a candidate’s name within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election. So under the old rules, the Club for Growth couldn’t broadcast an ad that said “Vote Against Barack Obama,” but it could spend that money on as many ads as it wanted that said “Barack Obama has ruined America — call and tell him to stop!” as long as it did so more than 60 days before an election. (The distinction between those two ads may sound silly and arcane to you, but that’s why you don’t sit on the Federal Election Commission.)

Citizens United and a couple of related court decisions changed all of this in two essential ways, and each of them was more incremental than transformational. First, the Supreme Court wiped away much of the rigmarole about “express advocacy” and “electioneering.” Now any outside group can use corporate money to make a direct case for who deserves your vote and why, and they can do so right up to Election Day. The second change is that the old 527s have now been made effectively obsolete, replaced by the super PAC. The main difference between a super PAC and a social-welfare group, practically speaking, is that a super PAC has to disclose the identity of its donors, while social-welfare groups generally do not.

[…]

Legally speaking, zillionaires were no less able to write fat checks four years ago than they are today. And while it is true that corporations can now give money for specific purposes that were prohibited before, it seems they aren’t, or at least not at a level that accounts for anything like the sudden influx of money into the system. According to a brief filed by Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader, and Floyd Abrams, the First Amendment lawyer, in a Montana case on which the Supreme Court ruled last month, not a single Fortune 100 company contributed to a candidate’s super PAC during this year’s Republican primaries. Of the $96 million or more raised by these super PACs, only about 13 percent came from privately held corporations, and less than 1 percent came from publicly traded corporations.

[…]

Which leads to an obvious question: If Citizens United doesn’t explain this billion-dollar blast of outside money, then what does?

You may remember that back in the ’90s, the most nefarious influence in politics emanated from what was then called “soft money” — basically, unlimited contributions from rich people, corporations and labor unions to both major parties. According to data from the Center for Responsive Politics, in 2000, the last presidential year in which soft money was legal, the two parties raised more than $450 million of it, divided almost equally between them. Only 38 percent of that came from individuals.

That all changed with the passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, popularly known as the McCain-Feingold law. The new law stamped out soft money for good, but it also created a vacuum in political fund-raising. The parties could no longer tap an endless stream of soft money, but thanks to the advent of the 527, rich ideologues with their own agendas could write massive checks for the purpose of building what were, essentially, shadow parties — independent groups with their own turnout and advertising campaigns, limited in what they could say but accountable to no candidate or party boss. Wealthy liberals like Soros and Lewis, along with groups like MoveOn.org, were the first to spot the opportunity. All told, wealthy liberals spent something close to $200 million in an effort to oust George W. Bush in 2004, setting an entirely new standard for outside spending.

Richard L. Hasen, an expert on campaign finance at the University of California at Irvine, recently wrote an article for Slate titled, “The Numbers Don’t Lie,” in which he showed that total outside spending, as measured through March 8 of every election season, seemed to explode after the Citizens United decision, reaching about $15.9 million in 2010 (compared with $1.8 million in the previous midterm cycle) and $88 million this year (compared with $37.5 million at the same point in 2008). “If this was not caused by Citizens United,” he wrote, “we have a mighty big coincidence on our hands.”

But there are alternate ways to interpret this data. The level of outside money increased 164 percent from 2004 to 2008. Then it rose 135 percent from 2008 to 2012. In other words, while the sheer amount of dollars seems considerably more ominous after Citizens United, the percentage of change from one presidential election to the next has remained pretty consistent since the passage of McCain-Feingold. And this suggests that the rising amount of outside money was probably bound to reach ever more staggering levels with or without Citizens United. The unintended consequence of McCain-Feingold was to begin a gradual migration of political might from inside the party structure to outside it.

And in his examination of raw numbers, Hasen managed to ignore what is probably the most relevant bit of data during this period: 2010 and 2012 were the first election cycles since the enactment of McCain-Feingold in which a Democrat occupied the White House. Rich conservatives weren’t inspired to invest their fortunes in 2004, when Bush ran for the second time while waging an unpopular war, or in 2008, when they were forced to endure the nomination of McCain. But now there’s a president and a legislative agenda they bitterly despise (much as Soros and his friends saw the Bush presidency as an existential threat to the country), so it’s not surprising that outside spending by Republicans in 2010 and 2012 would dwarf everything that came before. What we are seeing — what we almost certainly would have seen even without the court’s ruling in Citizens United — is the full force of conservative wealth in America, mobilized by a common enemy for the first time since the fall of party monopolies.

So, essentially, we’re seeing the continuation of existing trends—a rapid escalation in money flowing into politics and a rabid polarization that turns relatively trivial political differences into something tantamount to civil war—and the elimination of silly, artificial distinctions between electioneering and issue advocacy.

Simply put, the Koch Brothers and Sheldon Adelson would be pouring absurd amounts of money into defeating Barack Obama with or without Citizens United. If anything, that case actually served the public interest, in that at least we know who’s doing it. That wasn’t necessarily the case with the old 527s.

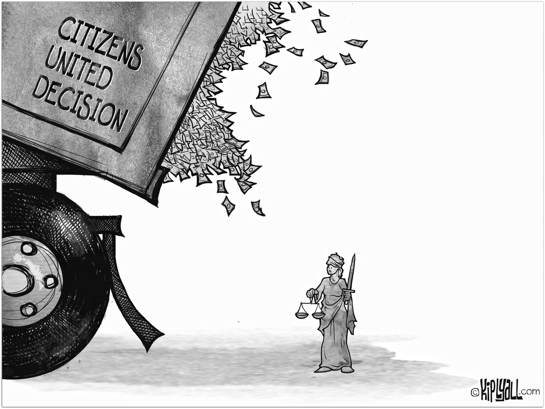

But getting the license plate of the truck is actually second best, to not being run over.

Great summary, excellent work by Matt Bai. When all is said and done, though, it reminds me of some of my gun friendly associates. They’ll see a story about a shooting with an “assault rifle” and their only reaction is “That’s not an assault rifle, it’s not full auto.” My reply is, “You’re correct. What’s your point?” If Citizens United is a handy catchall to collect outrage that “seventeen billionaires” may buy our government, that’s fine with me. The technical details can be sorted out if we ever develop the political will to do something about it.

Also, the gist of your story is that these billionaires took awhile to ramp up to this level of spending. Might that not also prove to be the case with corporations? Give it a few cycles.

So, what I get from this is that “soft money” was not as divisive. Since the money was spent by the “party monopoly”, the fringe groups had less impact. Which can be both good and bad.