What Happened to the Wage and Productivity Link?

What happened in 1970 to decouple wages and productivity?

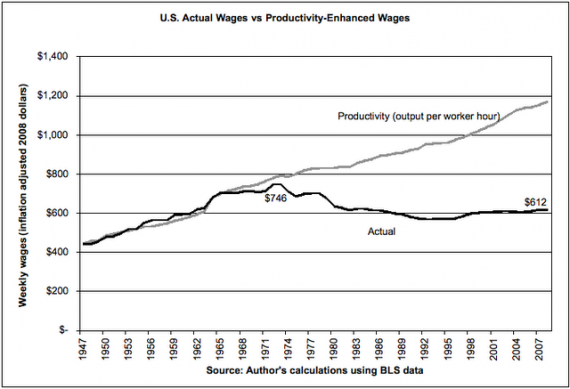

This chart has been making the rounds:

Real (that is, inflation-adjusted) weekly wages have been essentially stagnant since 1970 while productivity has continued its previous trend. This leads to an obvious question: What happened in 1970 to decouple wages and productivity?

This has generated discussion by, among presumably many others, American University doctoral student Daniel Kuehn, University of Michigan doctoral candidate Noah Smith, and NYT columnist Paul Krugman (who may have some economic training as well). A summary of the more plausible explanations offered by those authors and their commenters:

- Changes in technology (robotics, computers, etc.) which accelerated productivity while decreasing the need for skilled labor or, indeed, labor altogether.

- The end of Bretton Woods currency peg to gold. Smith:

It ushered in the era of floating exchange rates and ended the de facto gold standard that had prevailed since WW2. Why would this have held down wages in the U.S.? Well, it might have allowed the start of globalization, which began to add labor-rich, capital-poor countries to the rich-country trading system, thus holding down wages via factor price equalization. The catch-up of Europe and Japan in the 70s and 80s, and then of China et al. in the 2000s, might have held down U.S. wages as these countries’ catch-up productivity gains outpaced their wages. Alternatively, exchange rate risk must have spiked after the end of Bretton Woods; this could have reduced investment as a percent of GDP, raising the return on capital relative to labor, while simultaneously decreasing nondurables TFP via endogenous growth effects.

- Globalization writ large. Whether hastened by Nixon’s taking the US off the gold peg or otherwise, the massive US advantage in manufacturing was eroding by the late 1960s and exploded in the 1970s. The German and Japanese economic miracles, the rise of the Asian Tigers, etc.

- The collapse of labor unions and the ability of labors to collectively negotiate compensation.

- The rise of dual-income households. Dismissed by Smith, it was the factor that immediately sprung to mind when John Personna emailed me Smith’s post and I glanced at the chart. The women’s liberation movement and other factors made it the norm for middle class women to take jobs outside the home, both putting downward pressure on wages (by increasing the labor pool) and giving the illusion of higher living standards (while individual wages may have stagnated, household disposable income exploded). But, as Smith and Personna note, the trend was gradual and shouldn’t have impacted the trendlines so suddenly and drastically.

While his research has been divorced from the discussion, it appears that the source of the chart is Economic Policy Institute president Lawrence Mishel and his April posting “The wedges between productivity and median compensation growth.” He offers, by far, the most detailed analysis of the question.

The hourly compensation of a typical worker grew in tandem with productivity from 1948-1973. That can be seen in Figure A, which presents both the cumulative growth in productivity per hour worked of the total economy (inclusive of the private sector, government, and nonprofit sector) since 1948 and the cumulative growth in inflation-adjusted hourly compensation for private-sector production/nonsupervisory workers (a group comprising over 80 percent of payroll employment). After 1973, productivity grew strongly, especially after 1995, while the typical worker’s compensation was relatively stagnant. This divergence of pay and productivity has meant that many workers were not benefitting from productivity growth—the economy could afford higher pay but it was not providing it.

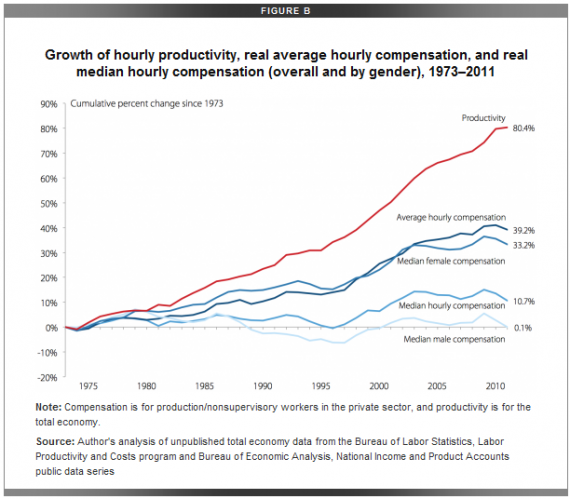

Figure B provides more detail on the productivity-pay disparity from 1973 to 2011 by charting the accumulated growth since 1973 in productivity; real average hourly compensation; and real median hourly compensation of all workers, and of men and of women. As Figure B illustrates, productivity grew 80.4 percent from 1973 to 2011, enough to generate large advances in living standards and wages if productivity gains were broadly shared. But there were three important “wedges” between that growth and the experience of American workers.

First, as shown in Figure B, average hourly compensation—which includes the pay of CEOs and day laborers alike—grew just 39.2 percent from 1973 to 2011, far lagging productivity growth. In short, workers, on average, have not seen their pay keep up with productivity. This partly reflects the first wedge: an overall shift in how much of the income in the economy is received in wages by workers and how much is received by owners of capital. The share going to workers decreased.

Second, as also shown in Figure B, the hourly compensation of the median worker grew just 10.7 percent. Most of the growth in median hourly compensation occurred in the period of strong recovery in the mid- to late 1990s: Excluding 1995-2000, median hourly compensation grew just 4.9 percent between 1973 and 2011. There was a particularly large divergence between productivity and median hourly compensation growth from 2000 to 2011. In sum, the median worker (whether male or female) has not enjoyed growth in compensation as fast as that of higher-wage workers, especially the very highest paid. This reflects the wedge of growing wage and compensation inequality.

A third “wedge” important to examine but not visible in Figure B is the “terms of trade” wedge, which concerns the faster price growth of things workers buy relative to what they produce. This wedge is due to the fact that the output measure used to compute productivity is converted to real, or constant (inflation-adjusted), dollars, based on the components of national output (GDP). On the other hand, average hourly compensation and the measures of median hourly compensation are converted to real, or constant, dollars based on measures of price change in what consumers purchase. Prices for national output have grown more slowly than prices for consumer purchases. Therefore, the same growth in nominal, or current dollar, wages and output yields faster growth in real (inflation-adjusted) output (which is adjusted for changes in the prices of investment goods, exports, and consumer purchases) than in real wages (which is adjusted for changes in consumer purchases only). That is, workers have suffered worsening terms of trade, in which the prices of things they buy (i.e., consumer goods and services) have risen faster than the items they produce (consumer goods but also capital goods). Thus, if workers consumed microprocessors and machine tools as well as groceries, their real wage growth would have been better and more in line with productivity growth.

Despite the generous excerpt, there’s actually much more to the post as well as a link to an issue brief at the link. Yet another graphic, though, will be helpful to the discussion:

Here, Mishel breaks down various trends both for the overall period (1973 to 2011) and for the major business cycles over that period.

Over the entire 1973 to 2011 period, roughly half (46.9 percent) of the growth of the productivity-median compensation gap was due to increased compensation inequality and about a fifth (19 percent) due to a loss in labor’s income share. About a third of the gap has been driven by price differences.

As impressive as all this data is, though, it really doesn’t answer the question. Indeed, it essentially restates it: What happened around 1970 (or, if you prefer Mishel’s date, 1973) that so radically reduced the bargaining power of labor?

Additionally, as one of Kuehn’s commenters (a Mr. or Ms. “Anonymous”) observes, there’s something odd about the data being compared:

Could this just be a relic of the data and methodology?

The productivity measure is a mean (sum of output divided by number of hours worked). Conversely, the weekly wage measure is probably a median measure. I think it would be more appropriate to compare the mean weekly wages to this productivity measure. As I recall from a review of ‘the Great Stagnation,’ while median wages are stagnant, mean wages aren’t due to increased positive skew in the wage distribution. So, perhaps there is not decoupling between mean productivity and mean wages.

Furthermore, I’m rather suspicious that the charts include only “production/nonsupervisory workers in the private sector” while “productivity is for the total economy.” After all, we moved over the period in question—although, again, not suddenly in 1973—away from being a manufacturing economy to an information and service economy. And more of us are now college educated and in white collar “exempt” positions. How much of the productivity gap displayed, then, is an artifact of carving out the best compensated non-owners?

Despite this incredibly long, by blog standards, setup, I don’t have any strong opinions on all this. I’ve got some questions, noted above, about the degree to which the charts show what they purport to show and think it quite possible that all of the factors above contribute to the explanation to whatever actual divergence between worker compensation and productivity has happened over the years.

It may not have been a single cause but a number of factors working synergistically. I’d add another factor: Nixon’s wage and price controls. It had a number of unforeseen effects among them being to initiate the driving of some kinds of light, relatively low margin manufacturing offshore.

An example would be the shoe industry. Until wage and price controls most shoes sold in the U. S. were made in the U. S. Wage and price controls produced leather shortages which constrained the production of U. S. shoes. That meant that we needed to import shoes to fill the gap.

On the wage side I think it’s “all of the above,” plus those misguided Nixon admin. regulations.

Then I also think you have to discuss Moore’s law, in the sense that the rate of technology growth that’s driven productivity gains greatly has outstripped even the nominal rate of wage growth.

As far as organized labor goes, it’s actually unfortunate the collapse didn’t happen a lot sooner, for in that event we’d still have domestic steel and textile industries and the automotive industry would not have needed to have been bailed out repeatedly and ultimately in large part taken over in bankruptcy.

Then I believe there’s an elephant in the room, although it doesn’t explain the 1970 thing: wages are not exactly the same as incomes and starting in 1980 material amounts of employee compensation have been in the form of employer matching contributions to employees’ 401k plans.

It was at the same time that we began to see the large divergence in wages. Income growth has gone almost entirely to the upper 1%, especially the top 0.1%. I don’t know how you can rationally believe that all of the productivity gains of the last 40 years are due to that group. Some people have made the claim , with some validity, that with a globalized economy there is a scarcity to capital, which results in higher returns to capital. However, I dont think that begins to explain the high salaries of CEOs, traders and other executives. IOW, much of that increase in productivity is also going to management.

I think that if we want to understand this better, it should be compared to what is happening in other countries. If this is from globalization, automation or women entering the work force, we should see those effects elsewhere also.

Steve

My first thought was to verify if they were taking into account the shift from direct pay to benefits in compensation. A click through to the Mischel paper indicates they used wages and compensation so they probably did incorporate the changing make up.

Still, it doesn’t appear they took into account the third consumer of productivity. Owners and workers gain from productivity but government also extracts a portion. It seemed the early 1970s start could indicate growth in the government take, via taxes, regulatory compliance, government insurance programs such as workers comp, unemployment, etc.

Nothing telling but if you google “US agencies 1973” you do see they made good start that year. The EPA got really rolling, the Endangered Species Act was enacted, the Rehabilitation act with Section 508 compliance for accommodation of disabilities, etc. I suspect a real examination would show many of the regulatory schemes now a part of working live came into being as the gap grew. This would indicate a shift in the portion of productivity going to government via regulatory costs and an incentive to go to non-human production to avoid those costs.

Now it is interesting that US v SCRAP was decided in 1973. It is called landmark in in gave law students (including Ralph Nader) standing to sue over IOC rail freight rate setting. I’ll leave it to the legal eagles but it seems this might be the case that permitted anyone and everyone to sue to stop projects over environmental concerns, although there has been pull back by the court in the intervening years trying to put the cat back in the bag.

@steve:

I’d like to see some data that shows that. I know that’s mostly been the case for the last 10 years, but since 1970?

Also, wages/compensation and income aren’t the same thing. Is there a direct relationship between higher returns on capital investments (where the 0.1% get a lot of their income) and wages? Honest question.

I could see how Dave’s point about price and wage controls could have an effect, but those lasted a relatively short time. I can see how 1970’s stagflation could have had that effect but again, that lasted a relatively short time.

It looks like a big chunk of the story may be due to increases in non-wage compensation, particularly health care.

Heh heh…. Thanx for the giggle James.

As to the meat of the post, as someone who entered the trades in the late seventies, I can say that we are VASTLY more productive now than we were then. Technology has changed everthing from tools (pneumatics, lasers, batteries… all of which continue to improve with time) to materials (too many to list, but even something as mundane as drywall is not the same product as it used to be). A house seems to go up in half the time they used to.

As to my compensation as a union carpenter, I seem to be doing OK… I don’t feel like I am underpaid….

But then, at 54, I am not going to be able to work much longer. The body is giving in.

@Andy:

There are some papers around that directly address that point. I’ll see if I can dig some of them up.

Once you’ve transformed a manufacturer like, say, Brown Shoe, into a distributor reversing the policy that induced the change doesn’t necessarily cause them to return to manufacturing.

I think it’s interesting what isn’t on the list. For many living in the 70’s the oil shocks were the most visible economic shock. Looking at a chart though, oil got cheap again by ’87 and stayed cheap until ’01. If that had been “it” wages would have had a good run in that period.

So I’ll stick with technology and globalization. We’ve been pretty much agreed on those for a while now.

Apple continues to be the exemplar. The company was created by bright and talented people who were attracted to rapid technological change and the opportunity for high personal income. Apple did try US manufacturing, and was in fact a hold-out. But they needed to go to Taiwan and then China to hit their price-point.

Apple contributes to high US GDP, Apple produces a few high incomes here, Apple produces a lot of manufacturing jobs overseas:

And so we can probably expect average wages to stagnate some more, for inequality to expand some more, and for “OWS 2020” to be really, really strong. Maybe they should have thrown them some bread rinds when they had the chance.

@JKB:

If that’s what it is, I’m sure you can find some dollars and cents charts to show it. Because to tell us your suspicions, is really just telling us where you are coming from. And we already know that.

@Andy:

However they are measuring inequality of compensation, it made a big jump from the 70’s to the 80’s.

@Dave Schuler:

Sure, patterns of business are stable, but new business beat a path to Asia as well.

IMO people put a lot of effort into thinking of reasons other than $1/hr wages and easy standardized shipping containers. Why?

(Jeez, in the 70’s everybody knew jobs were going to Taiwan for low cost labor. It’s funny how that obvious motivation, and the continued migration to low wage countries, is not a cool explanation anymore. We know jobs moved from the US to Ireland for low wages, and then moved from Ireland to Poland for lower wages. Just as they moved from the US to Taiwan, and then to mainland China, and then to Vietnam. I think this could be an example of successful GOP messaging. They want you to think of more obscure causes and to supplant the price thing. Not coincidentally, their wish-list of changes to US government are sold as reasons jobs go to China. They do not want you to think (now) $1.70 an hour and that still cheap shipping container is playing a major role.)

@Andy- My links are getting caught up in spam, but Piketty and Saez, Kenworthy and the Economist (just to name a few sources) have published numerous charts, graphs and data tables on income inequality. Median wages have been pretty stagnant since the mid-70s. At the same time, the 1% have seen large growth, but even there, most of that growth is in the top 0.1%.

@JKB- The things you cite might decrease overall productivity, but dont see why they would necessarily keep productivity gains from translating into compensation increases for the median worker.

Steve

A graph showing after tax income of various income groups would be even more striking, given the shift of the tax burden from wages to wealth effected by the Bush tax cuts on capital gains and dividends.

From what I can see, the people who run this blog want to see even more inequality, as evidenced by their support of Governor Romney’s candidacy and of Representative Ryan’s plans for Medicare and other social welfare programs. It would be nice if they could explain why they feel as they do.

I have the feeling multiple factors are involved, but I don’t think the issue of technology can be ignored when it comes to productivity.

There isn’t a manufacturing plant that doesn’t use some type of robotics. Changes in tools have been mentioned, and I don’t think the role the computer has played in pretty much every occupation can be ignored. I think the cell phone and data technology has really changed how people do business.

Sad, and related:

Our Ridiculous Approach to Retirement

The divergence in productivity vs. the wages necessay to purchase all of them is exactly why four years of $1.4 trillion deficits have not been inflationary, confoundng neo-liberal and austrian economic models. Consumer spending is simply not sufficient to drive national output anywhere near its maximum because real wages have been stagnant. This has also resulted in our persistent unemployment rates since the 1970’s: spending = incomes.

I am fairly certain that a similar graph for senior management types of workers would show that the link between increased out put and salary/wage compensation has not been stagnant.

There is all kinds of statistical evidence that the growth in the economy over the past 40 years has in varying degrees, benefitted the top 10%, 5% and 1% of wage earners.

There have been many structural changes in the economy – decline of the manufacturing base, decline in union represented employment, increase in technology and automation, more power shifted to upper management to reward themselves at higher rates of increase than for those in lower management or non-management positions.

@al-Ameda: I don’t doubt that’s all largely true. But, again: Why? What happened over the last forty years to make the top workers so much more valuable while the rest became so much less valuable? There have always been differences in talent, education, work ethic, and so forth—but they suddenly matter more than ever before. Why?

I was a manufacturing engineer in electronics assembly from 1972 – 2002. In 1972 nearly all circuit board assembly was done by hand. Components were prepped by workers and then hand soldered in circuit boards by others. Then along came industrial robots that inserted the components and solder wave machines that did the soldering. Suddenly 3 or 4 could do the work of 10 or 20. By the time I left the business (or it left me for China) nearly all components were surface mount and entirely done by robotics. Three or fours technicians could place 10s of thousands of parts an hour, something that would have taken 100s of assemblers to do. Industrial robots replaced the well skilled and well payed assemblers. The assemblers were required to take less skilled jobs that payed less while productivity skyrocketed.

@James Joyner:

It’s just the Justin Timberlake effect, or the law of large markets. Successful people of all stripes benefit because they connect to ever-growing audiences and markets. The number of top actors or top execs has not really gone up, but the number of people buying from them has. We now have billions of affluent people in the world.

And that’s the thing that strikes at any value-theory of the compensation. Pop stars don’t have to be the very best. They just have to be good enough, and then trip the right cascade of events that put them at the top of a market.

Execs hate us to understand that, because they’d like us to believe that they created all wealth created on their watch. They don’t want to think they were interchangeable with another exec with similar skills.

The GOP obviously has reason to reinforce the “hero” story, but there is no reason it has to be true. I think it much more likely that real heroes are rare, and that many more random winners cast themselves as such.

@Tsar Nicholas:

Except we do still have a domestic steel industry. In fact our steel production has continued to grow and we are the third largest producer of steel in the world. What really happened is that there has been a shift in production methods from producing most of our steel from raw iron to producing most of it from scrap metal. This lead to the decline of the large integrated steel producers (e.g. US Steel) and the rise of the mini-mill operations (e.g. Nucor). All the hand-wringing about production being driven overseas was really just an excuse for the established companies to lobby for legislation to drive up scrap metal prices to make the mini-mills less competitive. That is, it was appeal to xenophobia as a way of manipulating the domestic steel market.

BTW, this is part of the empirical evidence as to why I found Romney’s assertion that the GOP is the party of people who want to be rich to be so problematic a formulation. The post in question was here.

We are led to believe that if we just let the “job creators” have low taxes and less regulations that we will all be better off, but this assertion is not backed by the empirical evidence. I don’t pretend that a president can fix this problem or that there is a perfect set of policies that can be deployed, but I would like an honest discussion of the reality, rather than hand-waving over the magical effects of tax cuts.

@Stormy Dragon:

That’s the steel story I’ve heard as well.

Funny that he blames unions on textile decline. Our boxers are sewn in Vietnam because … well:

Seriously, what to people like Tsar Nicholas think, that without unions or our minimum ages we’d have all those great $97 a month jobs?

@Steven L. Taylor:

Yes, they are definitely related.

While dreams and aspirations are great, indeed fundamental to the pursuit of happiness, we need to be real about where we are.

Related, I noticed a funny book title at the library: The Happiness of Pursuit

@Steven L. Taylor:

In terms of the empirical evidence, it’s pretty simple: the Bush tax cuts have been in place for ten years now, yet unemployment has risen over the entire period. If tax cuts drive job growth, how come unemployment hasn’t dropped?

The best they can come back with is “well, things would be even worse without the tax cuts”, at which point the argument for the success of the Bush tax cuts is the same as the argument for the success Obama stimulus.

Even if we grants that lower taxes automatically lead to job creation, it’s obvious that this effect is being dwarfed by some other economic effect. We’d be far better off figuring out what that effect is and dealing with that then wasting all our time obsessing over swings of a couple percent in either direction in the tax rate.

@James Joyner:

James, it doesn’t seem to be sudden at all, the trend shows that this has unfolded over a 40 year period. To me, the more interesting questions surround whether or not we take a laissez-faire approach to the inequality, or whether we attempt to address it through the tax code or a number of ways. Right now, the rhetoric favors a minor increase in the tax rate on incomes over $250K, the electoral reality favors laissez-faire.

@john personna:

I suspect that textile production is in the same position as the Foxconn electronics plant, that is that the work that’s done there could be full automated, and that it is only being done by people as long as their wages are below the depreciation cost of the machine to do the same task. That is, if a job can be done by a $10,000 machine that lasts five years, it will only be done by a human if they can find one willing to work for $2,000/year or less.

@Stormy Dragon:

There are probably many jobs in textiles that could be automated. At the final stages though, flipping around garments and sewing varied seams is a fairly high skilled job. When robots get that good we’re all doooooomed.

@john personna:

Stories like this piss me off. Because I have been saving for my retirement and the proposed solution to this problem is invariably some variation on taking the money I’ve saved and giving it to the people who didn’t. So the grashoppers who blew all their income living beyond their means get both a more enjoyable youth while using my savings to fund their retirement, while the ants that denied short term pleasure to save get stuck with the bill for the grasshoppers’ party.

We labor under the illusion that we control the economy, or understand the economy. I don’t think we can do either. I think economics is about as advanced as 17th century medicine – they can describe symptoms but haven’t the foggiest idea why they occur or what to do about them.

We’re in the bleeding and purging stage of economic science. One said says bleed, the other side says purge, the patient doesn’t get better so each side demands more bleeding and more purging.

The fact that we are trying to make sense of James’ graph up there is proof that we don’t know. Right? We don’t know. We’re guessing and unfortunately while we guess we prescribe. It just so happens that the main prescriptions are policies that directly benefit some segment of the population (more for me!) and do nothing for the sick patient.

While everyone is developing pet theories the reality on the ground is that we have too few jobs and too much disparity. That is a recipe for social instability. Obviously jobs are going overseas and obviously jobs are going to robots (in the broadest definition of that word) – how could jobs do otherwise? If I can buy a machine for 100k that does a job for ten years, why would I pay some guy 500k over ten years?

Obviously we can’t live on Vietnamese wages and we can’t beat the robots, so obviously what we need is some societal adjustment to the reality that “the jobs” aren’t coming back. At least not to actual human Americans. And eventually the machines will also be cheaper than 3rd world wages. So again, we should probably be thinking about how society looks then, and how we get there, rather than cooking books to invent new excuses to make the rich even richer.

@Stormy Dragon:

I doubt that. Even if you have limited access to tax shielded retirement accounts there several other strategies to reduce tax exposure. There are gaping holes in the tax code for the very rich, and smaller fish can certainly swim through as well.

@James Joyner: In the case of upper management, they are not more valuable today than they were pre-70’s. They are paying THEMSELVES more money, which does NOT mean they are personally more valuable or productive.

The gap between wage growth and productivity growth is extra capital that can be invested. Creating that gap is what supply side economics or neo-liberal economics (depending on which side of the Atlantic you live) was all about. The people who decide how to invest the gap also get to decide how much to pay THEMSELVES. They all think they are genius (dont we all) so they think they created the gap in their companies themselves (even though the gap is universal) deserve a lot more money for doing so.

The mal-investment of that gap is the main reason we are in the current economic mess. It was suppose to be re-invested in new plant and equipment, making our manufacturing more efficient and more competitive, but if you off-shore your manufacturing, why do you need to re-invest in plant and equipment? So they used it to pay themselves huge bonuses, and endless cycles of M&A, or just put it in the bank like Apple does.

Historically, the US has had high labor costs and that high labor costs has driven innovation as capitalists have tried to find ways to make more with less labor. But now we ship jobs to the lowest labor costs, our productivity gains are not reflective in making more with less, they are from paying much less for more labor to make the same goods. We are using more labor and often more materials to make the same stuff. We hide this by paying labor much, much less. It is economical and profitable but it is not progress.

We have decoupled accounting productivity (spending less money to make the same stuff) from true productivity (using less labor and materials to make the same stuff). By definition, this means the best market solution is no longer the most efficient solution. This is a big deal as it basically means you can no longer trust the free markets to efficiently run the economy. The efficient allocation of capital no longer matches the efficient allocation of goods.

Some people think this is temp, that as low wage countries rise in wealth, labor costs will rise and we will re-couple economic productivity with true productivity. But that would mean an extended period of declining standard of living in high labor countries. Politically, I dont think that is a viable option.

@michael reynolds:

I’m reading “Debt, the first 5000 years.” You’d enjoy it. The author argues that economics is a mis-invention, selling “money makes the world go ’round” to a world that actually was going ’round without it.

(Before there was widespread money there were more relationships. Barter, where it existed, was between tribes. Money made us all tribes, and reduced relationships. Though, we probably still loan at different rates and conditions to our siblings than to strangers.)

If it is inevitable that more jobs not fewer are going to be automated, is it in our interests to welcome and accelerate that transition? Why be dragged kicking and screaming into the future?

The only reason we find automation threatening is because jobs are the main means for distributing income to most people. Do a job, get a paycheck,. buy the necessities. Jobs are the only way we have – under current thinking – to ensure that people don’t just starve.

But it’s not the only way for things to work. There are other systems. It may be that this system has invented its own successor. Why don’t we give some thought to living in the future rather than vainly trying to recreate a largely illusory past?

@Jib:

Right. Though as I say I don’t see it unrelated to pop and sports stars making tens of millions of dollars a year, either.

@michael reynolds:

The problem is that if you accept the globalization then you need the automation to compete.

@Ron Beasley:

That sounds about right to me. The machine tools shifted from increasing the productivity of the skilled worker to increasing productivity with no minute by minute workers and only a few highly skilled/compensated service personnel.

However, the graphs seem to follow this paper, with more productivity going to government regulation in the 1970s but the employee portion not rebounding with deregulation in the 1980s due to cheaper automation.

Although we should note, while prices and barriers to entry got deregulated to a degree, the march of regulation driving up the total cost of an employee marched on. Thus, employees must be far more productive on the first day to be a good liability to take on. Couple this with the decline in education preparing students to add any value to the company for a good long period even at 25 and with advanced degrees. They show up never having worked a day in their life and not prepared for the shift from “guest” (student/customer, whatever) to servant (be of value for others, namely the company and what they want you to accomplish). Let’s not forget the Academy has encouraged the youth to not go into fields that are scaleable but non-profits and government where work has a more one to one ratio rather than one to many.

@john personna:

I think you misunderstand my fear. My concern is that someday they’re going to just sieze my 401k and dump it into some national pension program, so I end up getting the exact same benefit as all those people who didn’t save anything get.

@michael reynolds:

The problem is that for the jobs you still need people to do (the engineers, the machnists, etc.) will we still be able to find them? If a large chunk of society gets an income while not really contributing anything, what’s the incentive to spend years getting and engineering degree and then work a job?

@john personna:

Right, so let’s automate and sell automation equipment and figure out a way for society to still function. Because we’re going to automate, regardless. It’s going to happen and pretending otherwise is like pretending the trains weren’t going to kill the pony express. If the train’s coming, let’s lay track.

@Stormy Dragon:

Heh, people like Mitt, with $100M in their 401Ks, will stop that from ever happening.

@JKB:

I read that paper, but I kind of see it like “in the midst of all this globalization, we still don’t like our regulation.” I don’t see where they can really show regulation as the limiting effect. I mean, businessmen love to say “I’m dropping this $10/hr job in Ohio and picking up this $1/hr job in China, because we have excess regulation!”

Really?

@Stormy Dragon: “what’s the incentive to spend years getting and engineering degree and then work a job?”

You see, the State will give every kid a test, then tell you what you’ll do. No incentive needed when your choice is do what you are assigned or take a bullet.

@Stormy Dragon:

That’s a big question. And there are other big questions. But if we know the paradigm shift is coming, why wouldn’t we prepare for it rather than indulging in nostalgia? Here comes the wave, get up on your board and ride it.

In specific answer, I think people will still do what they enjoy, and there would still be comparative advantages. I’m not talking forced equality, there would still be rich folks (and I’d want to be one) but if we cannot employ 100%, or even 90%, or in a few years 80% then we still need to feed those folks.

@michael reynolds:

Well, it would take a big cultural change to roll back the globalization. The economists sure changed the way people think on that one. Tariffs cause Great Depressions.

(Actually very high tariffs might, and high tariffs are protectionist. The trick was to make everyone believe that any tariff above zero was high and protectionist.)

The remarkable thing is that so many people are buying into this despite the lessons of recent history.

@Stormy Dragon:

FWIW, engineers and modern machinists (CNC programmers) will be fine. They can prosper in the large markets world. There will just need to be few of them, relative to customers and population. They will also need less support staff.

I remember when, to file copies of work, we had a girl at a documents counter. She’d take and file them. She’d even use a rubber stamp to give them a number. Now we have automated revision control.

@anjin-san:

The rich own the propaganda machine and the politicians.

@john personna:

Isn’t that just going to continue the income inequality problem? Most people simply don’t have the mind you need to be an engineer. If there’s a world where every has a basic income, except for a small cadre of people who have far higher incomes, aren’t we gonna to have the same issues we have right now?

@Stormy Dragon:

I don’t think we can or should try to eliminate all disparities of income. But we do need a way to cope with a future that likely includes less employment rather than more.

@Stormy Dragon:

Of course. That’s why some of us expect to see robo-socialism at some point. When your robot can sew inner seams on a ski jacket, most people will be on the dole. Hopefully with a big enough stipend to let them ski, occasionally.

Should we add an injunction against joining unions to the three laws of robotics?

@JKB:

Probably true, but my brother sees similar effects in the family business – construction – that’s largely immune to automation. For him, IT increased competition by making the bidding process more efficient even as the costs of employment have risen. So, like so much else, the business changed to one of low-margins where labor cost is typically the biggest component. It’s lower-cost to micro-manage low-bidding subs (who, in turn, employ low-cost, mostly Mexican workers), than to directly employ more skilled workers that need little supervision.

@michael reynolds:

A dream policy would probably nudge tariffs and lower payroll taxes. It would also prepare for large numbers of prematurely retired. I don’t see us avoiding that part.

It would be helpful to drop the moralizing in discussing issues like this. I’m not unsympathetic to Stormy’s comments but assuming that everyone who hasn’t got adequate savings was automatically a “grasshopper” who frittered it away doesn’t do anything to address the issue.

Before I accept the notion that wage and net worth inequality in America is due solely to economic factors, somebody needs to explain to me why the same economic causes haven’t produced the same effects in Germany or the Netherlands.

@Stan: That is an excellent question that stirs my comparativists’ heart. What are the comparative numbers on this issue and what might they tell us?

@Stan: Germany actually has greater income inequality than the US – they are just a lot more redistributive, so taxes and transfer payments mask the inequality. In other words, Germany has greater before tax-and-transfer income inequality than the US, but less after tax-and-transfer inequality. Here’s a comparison.

@Steven L. Taylor:

All true and I share your skepticism of that narrative. On the other hand, I’m just as skeptical that the narrative coming from the other side is the grand solution to all our problems. Hence I’m a man without a party.

To get all partisiany it sure looks like the disconnect starts in 69, gets worse as Gerry’s WIN fails, starts to recover under Carter but reverses trajectory and gets slowly worse through today. All of area between the curves is going somewhere.

My wife and I are behind on retirement savings due to the costs of a serious illness in the family. I suspect this happens a lot.

@Andy:

Thank you, Andy that was an interesting link.

Did international investment go up after 1970? We’ve discussed the idea of a corrosion of Labor’s bargaining power, but what if what happened was that we have had a drastic increase in the bargaining power of Capital?

Capital has pretty huge exit power at this point. People owning it can pull out their money and change its allocation far more easily than workers can change their skills and their jobs, and owning it seems to generate more for yourself faster than most gains in income.

@anjin-san:

I’m sure. I just saw the statistic that $35B has been removed from retirement plans as borrowing and then default. (Borrowing against balance.) I assume that much of this was medical was well.

I just stopped by because I saw this at interfluidity:

As Waldman notes Dude wrote that in 1943.

@john personna:

Thank you for the link, John. Interesting data, interesting observations.

I remember coming across Kalecki in college while studying Keynesian economics. Kalecki’s articles were were part of curriculum readings on macro economics and business cycle analysis. Needless to say, I hadn’t been back to Kalecki since that time.

@Andy: Very informative, and thanks for the link. Your data makes my point. Germany and many other countries compete in the same world economy as we do but their political process tries to prevent what we have here, a two class society. Somehow, we in the US don’t feel much solidarity with our fellow Americans. Remember Rick Santelli’s famous rant about how awful it would be to help the ‘losers’ who were underwater on their mortgages? And who can forget the many Wall Street Journal editorials about the ‘lucky duckies’, those people so fortunate that they’re too poor to pay federal income taxes. To my mind, the explanation for the graph at the top of this thread lies more in moral attitudes than in economics, and to understand our present situation we need de Tocqueville more than Adam Smith.

@Stan:

You also would like “Debt, the first 5000 years.”

The US has been rather extreme in looking at “life as economics,” with pop-culture books that take it to the extreme. It is a choice of view, something the typically inculcated economic-American has a hard time seeing.

I don’t know if this thread is still alive, but if it is I suggest reading the article in today’s New York Times about what Caterpillar is doing to its workers. The company is profitable, the top executives are doing very well, and the production workers are getting shafted. This is progress?

In my last college economics class (taken in 1956!) the professor, Handsome Al Mandlestamm, as he described himself, said at the end of the term that he wasn’t sure about the usefulness of a purely economic approach to wage structure. As he put it, the people at the top had carte blanche in setting their own wages as far as economics was concerned, but were restrained by public opinion and by their own consciences. The guy knew what he was talking about.

@Stan:

At Caterpillar, Pressing Labor While Business Booms

Pretty sad, because just about every article about the strength or revival of US manufacturing features Caterpillar on the front page.

@john personna: It’s pure greed when Caterpillar executives give themselves large pay raises while requiring everyone else to take wage cuts. Never does it seem to occur to executives that their pay should be restrained so as to ensure future competitiveness.

First, thanks for JJ for bringing this up. Not that I haven’t seen it, since I frequent liberal blogs that have been all over these charts. But I like seeing the OTB take on it.

I really don’t know what the answers are. I strongly suspect a combination of: a) “globalization;” b) automation; c) a change in ethics at the top; and d) changes in government policy that reflect the new ethics at the top (e.g. tax cuts that mainly benefit the tippy top). Maybe throw women-in-the-paid-workforce in there too. But a+b seem powerful enough all by themselves.

@Rob in CT: As the case of Germany shows, a + b is necessary but not sufficient to impoverish production workers. You need c + d to do the trick. And I’d add e), the moral squalor of modern day conservative thought.

Related:

Such “see/handle money” effects are by now well documented. Basically the economic view, the money view, has feedback which operates on the subconscious level. For all econ’s claim of rational consumers and choices, it affects us in much more subtle ways.

Ronald Wilson Reagan.

An almost direct correlation between Reagan’s election, the greed is good ethos among Republicans and the increase in inequality.

@Loviatar: Granting that some argue time isn’t linear but, generally, something that happens after (1980) a trend started (1970/3) isn’t considered a likely candidate as its cause.

@James Joyner:

Because a trend starts doesn’t mean it continues unless there is a strong trailing wind.

So while de-linkage of Wage and Productivity and the rise inequality may have started in 1973, but you can’t tell me that Reagan’s presidency and the ethos it engendered among the modern Republican party (vastly different from the pre-1980’s version) didn’t accelerate and perpetuate that trend.

——-

How top executives live (Fortune, 1955)

I think “Reagan done it” is simplistic. Or perhaps that’s an example of my “d” above (gov’t changes codifying ethical changes that had already happened at the top). Not that electing him didn’t have consequences, but Carter started deregulating things (including beer! Thanks, Jimmy!).

The thing I keep coming back to is that the “great compression” era 1950-1970 was an outlier. The “Gilded Age” is more… well, for lack of a better word, “normal.”

Personally, I find that pretty scary.

Does that chart include benefits? That is, is it looking at total compensation, if not, then this discussion is a huge waste of time.

@Steve Verdon: The point is to discuss why decoupling of weekly and hourly wages from productivity growth so no, it isn’t a waste of time. In fact this is where, were you interested in a fruitful discussion, you’d suggest rapid growth in benefits such as health-care contributions from employers is responsible for the decoupling. Workers had health-care before 1970.

@Steve Verdon:

It is hardly the only chart to show the same trend. The NY Times is taking this up with a new series. They chart they show, not of individual but family income, looks much the same. As I was saying to James, I think the rise of dual income families in the same timeframe was response to decline in individual income and not a cause of it.

A Closer Look at Middle-Class Decline

We probably agree with the opening paragraph:

Though perhaps you are contesting the second:

Ben,

If you ignore benefits then you are ignoring a major component of employee total compensation. If for some reason health care started to grow faster in 1971ish than prior then that could be the very reason for the decoupling. Failing to consider that is a major flaw.

Now, why might there be such a divergence of employee overall pay into health care benefits? Couple of things,

1. As Dave Schuler has alluded to, Nixon’s wage and price controls might have done that. Firms might then compete on non-wage benefits.

2. By 1971 Medicare was 6 years old, was it finally starting to have an impact on health care prices as some of the largest consumers of health care get a nice subsidy?

3. Similarly with Medicaid.

Firms care only about the total cost of employing a worker. To them benefits and wages are all pretty much the same thing. Further, with a wage freeze increasing or offering a better benefits package would be one way to compete for workers.

As for Medicare and Medicaid we can return to a very basic very non-controversial result of economics: subsidize something you get more of it. In this case consumption of health care. This would act like a positive demand shock. This would drive up prices which would automatically increase the non-wage portion of an employees compensation package. From the employers view that is like a raise. If non-wage benefits are say, 20% of total compensation and they go up by 6% that is a 1.2% increase there. If the firm is going to offer a raise commensurate with a rise in productivity over time and that is 2% that leaves only 0.8% for wages.

There you go, a decoupling. That is one theory. Failing to consider it means you are biased.

John Personna,

That there is more than one graph tells us nothing. We are looking for the reason, not debating whether or not that it is happening.

In other words, if my conjecture is correct (and I’ll point out that none of the explanations so far, aside from Dave Schuler’s) even considers the health care angle underscores why it is important to reform health care in such a way as to reduce the increase in prices and costs. To bend the cost curve down, so to speak. Adding more people who have coverage is nice, but it will merely exacerbate the sustainability problem.

@OzarkHillbilly: I once read a book about a boy from the Ozarks who wanted a hunting dog so bad he could taste it. He sold blueberries and used magazines to fishermen until he had enough to buy 2 dogs. When he got to the train station to pick them up, amazingly enough they were already named! A little pink slip had the two dogs’ names clearly stenciled: Carter and Clinton. The station master Perot told him to leave those no good red bones alone, or NAFTA would pass by the station without a problem, but the boy didn’t listen. Now he has a blue badge with smiles on it and a great job saying hello to people.