When Compromise Is Immoral

150 years ago, President-Elect Abraham Lincoln was presented with a chance to avert Civil War. He passed it up, and we should be glad that he did.

As part of their ongoing coverage of the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War, The New York Times makes note of the Crittenden Compromise, which was the last-ditch effort to avert Civil War and placate the seceding states of the Deep South:

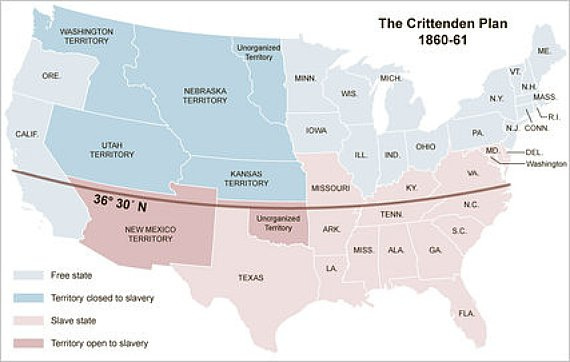

Crittenden hoped to achieve a lasting peace—not just a truce—through a geographical and constitutional “solution” to the slavery crisis. First and foremost, as shown on the map, Crittenden restored the Missouri Compromise line that had been nullified in 1854 by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. By reintroducing this line, and extending it west to the California border, Crittenden hoped to restore the tenuous peace created by a clear geographical distinction between slavery and freedom. Slavery would be permanently prohibited north of this line, thereby reversing the Supreme Court’s 1857 ruling that Congress had no right to regulate slavery in the federal territories.

In territories south of this line, however, the federal government would have no say over slavery; instead, the decision to allow or prohibit slavery would be made by those living in the territories themselves. And in a minor phrase that could easily have been overlooked, the compromise ensured that any territory “hereafter acquired” south of this line would be left open to slavery. This, Lincoln was quick to note, opened the possibility of colonizing parts of Mexico or the Caribbean for the extension of plantation slavery.

Abraham Lincoln had been elected President in November 1860, but under the Constitutional provisions in place at the time he would not take office until March 4, 1861 so the job of trying to save the Union fell to lame duck President James Buchanan, who had largely done nothing to stop the increasing fractures between north and south during his time in office. The Crittenden Plan was one of the efforts made during the lame duck period to avert disaster, but it fell apart for many reasons, not the least of them being Lincoln’s opposition:

Lincoln was also actively working to end the crisis, though he had his limits. In an exchange of letters with Alexander Stephens of Georgia, a former fellow Whig who had served with him in Congress, Lincoln insisted that Southern slaveholders had nothing to fear from his election, and that he did not want to interfere with slavery where it existed. But he also acknowledged the essential problem: “You think slavery is right and ought to be extended, while we think it is wrong, and ought to be restricted. That, I suppose, is the rub.” When North Carolina Unionist John Gilmer asked Lincoln to reassure Southerners that he had no intention of interfering with slavery, Lincoln wrote that his record was clear, and that he did not want to appear as someone apologizing for having won office. And when the Buchanan administration asked him to support the Crittenden Compromise, he refused, for these measures might temporarily ease the crisis, they would not solve the underlying conflict.

It’s important to note, of course, that opposition to the expansion of slavery into the western territories was a central tenant of the new Republican Party, and of Lincoln’s campaign for the Presidency. Therefore, it isn’t at all surprising that he would have opposed a plan that would have extended the reach of the slavocracy to the Pacific Ocean. Nonetheless, Lincoln’s role in torpedoing the Crittenden Plan has led some Southern revisionists to charge that the war was his fault, but as Seth Masket points out, this was one situation where compromise was not possible:

It’s interesting to imagine, though, what would have happened if it had succeeded and actually prevented war. Lincoln surely would have been pilloried by the abolitionists but praised by whomever the 1860 equivalent of David Broder was. And, no doubt, Lincoln’s refusal to compromise was, in some sense, reckless, hastening war. But 150 years later, Lincoln’s partisanship and obstinance seem like the proper course; bipartisanship would have been immoral.

Most especially because it would have enshrined slavery in the Constitution even more than it had been in 1787 through a series of Amendments:

- Slavery would be prohibited in any territory of the United States “now held, or hereafter acquired,” north of latitude 36 degrees, 30 minutes line. In territories south of this line, slavery of the African race was “hereby recognized” and could not be interfered with by Congress. Furthermore, property in African slaves was to be “protected by all the departments of the territorial government during its continuance.” States would be admitted to the Union from any territory with or without slavery as their constitutions provided.

- Congress was forbidden to abolish slavery in places under its jurisdiction within a slave state such as a military post.

- Congress could not abolish slavery in the District of Columbia so long as it existed in the adjoining states of Virginia and Maryland and without the consent of the District’s inhabitants. Compensation would be given to owners who refused consent to abolition.

- Congress could not prohibit or interfere with the interstate slave trade.

- Congress would provide full compensation to owners of rescued fugitive slaves. Congress was empowered to sue the county in which obstruction to the fugitive slave laws took place to recover payment; the county, in turn, could sue “the wrong doers or rescuers” who prevented the return of the fugitive.

- No future amendment of the Constitution could change these amendments or authorize or empower Congress to interfere with slavery within any slave state.

In his famous “House Divided” speech in 1858, Lincoln said that America could not exist forever as “half slave and half free.” Had the Crittenden Plan been adopted, it would have sent us on a course of being, fully, a slave nation. It was a compromise with evil, and Lincoln was right to reject it even at the cost of 600,000 lives.

Did this proposal mean to turn Virginia into a free state?

OK, granted, The problem with this “is obvious right off the bat; there are those who will reject the” and the logic there and because of its source. I will make a point about the intellectual bigotry involved with that, at need.

That said, Point 3, particularly, is relevant today, given that so much of the time we hear arguments about how words don’t actually mean things, or we see progressives trying to change the general usage of a word, or a phrase, to their own advantage.

It’s also interesting, and given that Jared Lochner often expressed the viewpoint that words don’t mean things. Words, he said, are meaningless.

Perhaps more to the point; is the compromise of one’s principles in itself evil? Certainly an argument to be made to that point; after all, if one considers that one’s principles are not evil, what then is compromise of one’s principles, but a compromise with evil? When, then, is such compromise ever moral?

I’m sure that many on both sides of the HCR issue would tell you that they consider compromise in that area to be “immoral” not to mention how many zealots on the right who consider progressive tax rates to be “immoral” and on and on…

Lincoln followed Andrew Jackson’s example during the nullification crisis. Neither would compromise on the basis of an illegal threat to secede. To do so would have been to capitulate on everything.

In Lincoln’s first inaugural he indicated he would support a constitutional amendment that reflected his own policy of non-interference by the federal government with slavery in the states in which it already existed, though he said it wouldn’t be needed. I wonder if any amendment could have obtained the super-majority needed anyway.

So they are, AIP. Your point?

When it averts a greater evil, or creates a positive good sufficient to outweigh the evil, I suppose. But this feels like it should be a cage match between some old Greeks, a few Germans and a Jesuit or two.

My point is that the “immoral” tag gets attached to a lot of things these days…enslaving other human beings really is immoral while taxing income at different rates, not so much…

Does that mean you’d like to see a flat tax?

Interesting

Well answered.

Trouble is, history shows us that such aversion is temporary at best, but the precident for acceptance of evil far outlives whatever temporary good had by ignoring principle.

“Does that mean you’d like to see a flat tax?”

Not really…not quite sure how you came up with that…

Here’s a question for you though…do you equate in any way the immorality of slavery with the “immorality” of a progressive tax code?

WEll, you’re the one who suggested, with:

… that taxing people at different rates is immoral. I agree. It is.

That’s what a flat tax does… it taxes everyone the same.

So, I ask again…..

And the obvious answer to your question is, yes, I do equate the two.

I suspect the Crittenden Compromise would have ultimately led to the US severing into two countries anyways, had it been adopted (although it might have been a more peaceful split). Opposition to slavery was building in the North and the West, and at the same time the South was becoming more vehemently pro-slavery.

“Not so much” means no, it’s not…I thought that would have been obvious…

AIP: Your adherence to the moral double standard on the altar of class warfare is thus noted.

Being less evil isn’t enough to make something good, nor is being less wrong enough to make it right. Morality is about what is right, not simply what is best.

So it is a “moral double standard” to be opposed to slavery but not to a progressive tax code? Oh my…

AIP…

Clearly, you are a bad person.

The conversation going on here is about a deep as a petri dish lid. A pox on all your houses!

Why BitEric is doomed to a life of perpetual disappointment and anguish, Data Point No. 1,235, 769:

Doug, I am not sure of your point here. Was the Crittenden plan an “immoral” compromise because it wouldn’t have worked to preserve the Union or because it would have “enshrined slavery in the Constitution even more than it had been in 1787”?

Lincoln’s original proposal to the South was to allow slavery to continue in the existing states until 1900. And during the war, the Great Emancipator said twice:

The vast majority of Northerners agreed it was far more important to keep the Union together than it was to free black people from slavery, which is probably part of the reason why Lincoln said it. If the South had responded to the invitation of the Emancipation Proclamation to lay down their arms in exchange for keeping their slaves, I think Lincoln would have accepted that compromise, more or less happily.

But Lincoln rejected the Crittenden Compromise, so hauling his name into support it makes no sense. Why did Lincoln think it was immoral? Because it permitted the expansion of slavery, the very thing he was voted into office against.