Has National Debt Increased More Under Obama Than Bush?

Obama has borrowed slightly more money in 3 years than Bush did in 8. Does it matter?

CBS’s Mark Knoller made a splash with a piece headlined “National Debt has increased more under Obama than under Bush.”

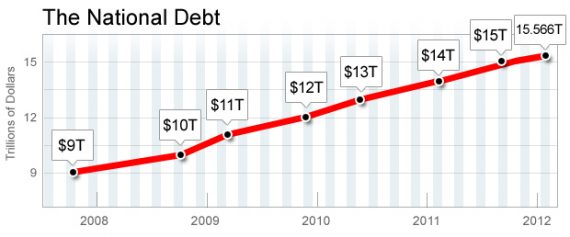

The National Debt has now increased more during President Obama’s three years and two months in office than it did during 8 years of the George W. Bush presidency.

The Debt rose $4.899 trillion during the two terms of the Bush presidency. It has now gone up $4.939 trillion since President Obama took office.The latest posting from the Bureau of Public Debt at the Treasury Department shows the National Debt now stands at $15.566 trillion. It was $10.626 trillion on President Bush’s last day in office, which coincided with President Obama’s first day.

The National Debt also now exceeds 100% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product, the total value of goods and services.

Mr. Obama has been quick to blame his predecessor for the soaring Debt, saying Mr. Bush paid for two wars and a Medicare prescription drug program with borrowed funds.

The federal budget sent to Congress last month by Mr. Obama, projects the National Debt will continue to rise as far as the eye can see. The budget shows the Debt hitting $16.3 trillion in 2012, $17.5 trillion in 2013 and $25.9 trillion in 2022.

This are all true facts. But Crooks & Liars‘ Blue Texan says “the piece is BS.”

What Knoller doesn’t specify, naturally, is what the debt was when Bush began his presidency. And that’s a glaring omission, because unless you don’t know that, you can’t accurately compare the records. So here it is.

In 2001, the national debt Bush inherited was around $5.7T, give or take. Some of that debt in 2001 has to be attributed to Clinton, just as some of the debt in 2009 when Obama took office has to be attributed to Bush. When W. left office in 2009, the debt was nearly $11T. That’s an increase of 89 percent.

Under Obama, the debt has increased from about $11T to about $15T, about 40 percent.

And what’s behind that increase? Historically low taxes and historically low revenues — and the worst financial crash since the 1930s. There’s been no “binge” in spending, as Knoller wants you to believe.

With the exception of the last sentence, these are also true facts.

Of course there’s been a spending binge under Obama; that’s the whole point of stimulus spending! So, Obama increased the debt some $700 billion in his first few months in office. Since then, as Blue Texan notes, we’ve taken in much less money than we otherwise would have because of a lousy economy and, yes, because of very low taxes compared to our historical norms. And not just because of the Bush tax cuts, either, but also because of the Obama payroll tax holiday.

Knoller is right that, in simple dollar terms, the delta under Obama has been higher than under Bush. $4.939 trillion is indeed bigger than $4.899 trillion. Blue Texan’s insistence that we should look at the numbers in terms of percentage of increase is also plausible, although not if we’re going to compare eight years to three! On an annualized percentage basis, Obama still beats Bush.

But, again, that’s not shocking! Bush inherited a mild recession that quickly righted itself. Even the massive spending on two wars and the Medicare drug boondoggle wasn’t as hard a hit as the Great Recession, whose effects have occurred mostly under Obama.

Overall, I’d argue that the “who increased the debt more?” debate is rather silly. The bottom line is that Bush and Obama have continued an American tradition that’s been the norm my entire lifetime: spending without regard to revenues. Bush wanted to cut taxes while funding two wars and a domestic legacy. Obama wanted to create an even bigger domestic legacy–a major move towards universal healthcare coverage–while ramping up a war and stimulating the economy. The key difference is that Obama’s preference was to also raise taxes–albeit only on top earners–to help pay for it; Congressional Republicans blocked that effort.

UPDATE: Doug Mataconis wrote about this separately in “Debt Under Obama Increasing Faster Than Under Bush.” Since I didn’t notice before comments started on this post, I’ll leave both up rather than consolidating my thoughts as an update to his post, our usual practice in these cases.

Most all of the spending which has occurred under Obama has come from automatic stabilizers in response to a worsening economy, not discretionary spending. Budget cutting would be ultimately counter-productive because the stabilizers would simply ramp up spending to compensate. If you want a lower budget deficit, get people back to work.

@Ben Wolf:

Discretionary spending has been going down for several years because it is being pushed out by automatic entitlement spending. Of course, no politician wants to take the heart for trying to get entitlement spending under control so the debt keeps going up.

What Americans have to face is that they like high levels of government spending. Americans just do not want to pay for it. Progressives and conservatives should agree on immediately raising taxes so that there is no deficit. In realtiy, taxes should be raised high enough so that the national debt can be paid off as fast as possible.

If everyone taxes doubled, then people would not support government programs so much and the government and the economy would find a sustainable level of spending and taxes. The worse situation is what we have know, people are getting government at a $1.3 trillion dollar discount due to deficit spending.

If all other things were equal, this would indeed be damning.

All other things, are not, however, equal. The 2008 crash meant a lot of this was simply baked into the cake.

The Stimulus (~1/3 of which were magic tax cuts, remember) was new spending, albeit in direct response to the worst downturn since the Depression.

Now this is largely true. It’s nice when I get the occasional opportunity to agree with sd.

This is foolish because of the word “immediate” (and “as fast as possible”), but the general idea there is sound. We should actually pay for the things we want – or adjust what we want. Of course we’ll still need to wrangle over exactly who pays (but in the end, for all the whining and gnashing of teeth, you cannot get blood from a stone, so it’ll be those of us with money who pay).

Just remember, sd, which party it was that convinced the American people that they could have their tax cuts and their spending too. It was the “Conservative” party. And the leaders of that party are still doing that. Every GOP proposal to deal with the deficit includes tax cuts, largely ignores the military, and either tries to pile it all on entitlement cuts or engages in magical hand-waving to avoid that (e.g. assuming ridiculous rates of economic growth).

Indeed. The question is how, exactly, to do that (not just in the short term, but generally going forward).

@superdestroyer: Virtually every thing you wrote is factually inaccurrate and/or based on an incorrct understanding of finance. I’d recommend some reading to you if I thought you’d actually do it.

This really is an excellent post.

Indeed, this “Blue Texan” character to which reference is made is correct on all points except of course until he or she said there hasn’t been a spending binge under Obama, which is not even ship-to-shore close to being accurate and somewhat is akin to saying there wasn’t a drinking binge in Charlestown on St. Patty’s Day.

Of course there’s been a massive spending binge under Obama. The so-called Stimulus package. QE 1. QE 2. Continued bailouts of Fannie and Freddie. The banks. The auto bailouts. “Cash for Clunkers.”

A few other points are worth mentioning:

1. Raising taxes on high wage earners during a weak economy with a weak job market is tantamount to deciding to treat one’s headache by severing one’s head.

Not every high wage earner falls into the Dennis Kozlowski category. For every “corporate fat cat” caricature pushed by the liberal media there are a lot more small to mid-sized business owners out there who don’t fly lear jets, who don’t own castles in the Caymans, but who do create and maintain vast numbers of good jobs.

It would be a monumental mistake to raise taxes in this economy. We need first to cut spending and then to engage in revenue-neutral tax reforms.

2. We’re well past the point at which we still can play the whole reduction in rates of spending are actually spending cuts shtick. We need to cut programs, in nominal terms, not to engage in window dressing. We also need to deal with the “third rail” problem. It’s heading towards being an unmitigated disaster. If we don’t substantially raise the retirement age for people born after 1965 or thereabouts and if we don’t initiate some sort of private account system along the lines of the HSA program then your kids and their kids (assuming the former even will be able to afford kids) are going to have substantially lower standards of living than you and I.

@Ben Wolf:

I suggest you take it up with the CBO then. Are you really go to argue that most Americans like big spending government as long as someone else pays for it. Are you really going to argue that the budget deficits have been well over $1 trillion dollars each year for the last four years. Are you really going to argue that the best way to reign in the size of government is to raise taxes (more than double income taxes) so that people have to pay full fare for the government that they want?

I guess when you believe in free ponies for the 99%, then everything else sounds bad.

opps, for the link on discretionary spending as a percentage of GDP.

http://www.cbo.gov/publication/42519

@Tsar Nicholas II:

None of these events other than TARP (which began during the Bush Administration) are “spending”, nor do they have any impact whatsoever on the public debt.

A spending cut is a tax increase. You’ve totally contradicted yourself.

All you’ve done is make a vague prediction of doom with no specifics as to how this financial apocalypse will materialize or by what mechanism it will triggered. No one is going to accept an analysis which fails to rise beyond the level of “public debt = bad.” You’ll need to do better than this to persuade people.

@superdestroyer:

Yes. Your proposal is economic suicide.

Can you not see that these two things are opposite sides of the same coin?

There are reasons I think raising taxes on the well-off will not have as dramatic an impact as spending cuts might: Tax rates (particularly on high earners) are very low, by post-WWII standards.

There are a lot of people who have taken their tax cuts and put the money in the bank (which, at least in more normal times, gets lent out and that’s all well and good), instead of buying stuff. The reason for this is that if you’re already well-off and you get a tax cut, you don’t suddenly say “oh, great, now I can afford that new washing machine!” I could already afford the washing machine, before the tax cutting. Whereas a working class person who gets a tax cut (like, say, the payroll tax cuts the Dems like and the GOP hates) might go out and buy that washing machine.

Tax cuts can be stimulative, I think we all agree. But when tax rates are already low you get diminishing returns, no? Also, the best bang-for-the-buck would be tax cuts targetting people who are likely to spend the money, rather than targetting people who will just bank the money.

Spending cuts do need to happen. We will probably end up raising the retirement age. I think means-testing benefits makes sense. We will continue to battle the healthcare spending beast. The military budget needs to be reduced too. All of that is true. But it’s only one side of the coin.

The Affordable Care Act has a net negative effect on the federal budget deficit. Barack Obama is doing more to service the nation’s fiscal health than George W. Bush ever did.

@James:

We hope it has that effect, anyway. The CBO projects it will, and I certainly hope it pans out. But obviously the ACA hasn’t kicked in fully yet and it will be years (decades, probably) before we know whether or not it really bent the cost curve. At best we can say that it is likely that it will help.

Agreed?

@superdestroyer:There is no mechanism by which discretionary spending is drained by automatic stabilizers. Discretionary spending drops when spending cuts are made. You’ve just acknowledged the Obama Administration has been attempting to reduce the budget deficit.

@Rob in CT: That’s absolutely fine by me. I think we can both agree that the Affordable Care Act, at least, makes more attempts at cost control than Medicare Part D.

Wait James.

The chart I linked to in yesterday’s discussion shows a lower per-capita increase in spending under Obama versus … well versus most past presidents.

I think the thing that might be hidden is that sure there was stimulus, but there weren’t all the other sorts of increases we usually have with a spend-friendly (and president-friendly) congress.

Here is the article:

Per Capita Government Spending by President

As I understand it, that data includes stimulus (Obama, Bush, and past).

But this was only in response to the most serious slump since the thirties and it was a one off that has added about 675 billion to expenditures over the last three years. During Bush’s last calendar year in office when he was also responding to the recession which started in December 2007 his actual expenditures were around 1.3 trillion which is about the same as fiscal 2011. Aside from the stimulus program which was an administration decision although taken under duress Obama has added very little to the deficit, it’s all essentially the product of committments entered into during the Bush era (like the wars and part D); expenditures associated with the recession like unemployment insurance; and lower tax receipts partly resulting from the recession and partly from the Bush tax cuts. And it’s not as if the Republicans are particularly serious about the deficit since they absolutely refuse to address the revenue side of the equation. Exhibit A here is Ryan’s budget which has to be one of the most fatuous documents ever to emerge from the halls of congress.

Your conclusion is deeply wrong.

Bush II spent with a grand, worlds-changing vision. (Plural “worlds” because his plan included Mars.)

Obama has been (as that data shows) restrained. Yes he has spent on big visible items, like stimulus, but they don’t actually add up the way wars and Medicare Part D do.

Your analysis is partisan and not data driven. Sir! 😉

As I mentioned yesterday, I think the key is that Republicans in Congress were happy to spend for Bush, but will not spend for Obama (in the same way they would not spend for Clinton).

If you want small budgets a Democratic President and Republican Congress might be the way to go. The only problem is that this combination doesn’t get a good handle on taxes.

@Tsar Nicholas II:

I should stick to military history if I were you. Other than the stimulus and programs that came out of TARP (which was a carry over from Bush) these were not SPENDING. You obviously have no idea what QE means.

Just to document the point:

http://projects.nytimes.com/44th_president/stimulus

I added up the tax cuts and got $263.33 Billion, or 33.46%

[one thing I found amusing was that renewal of the AMT patch was included in the Stimulus bill. They do that every year… It cost $69.8B. If you remove that, the stimulus tax cuts were $193.53B out of $717.2B, which is 27%]

So roughly 2/3 of the Stimulus Bill was new spending – $534 Billion (which was swallowed by state cuts, IIRC). That’s the “spending binge” at least wrt to the Stimulus Bill. The tax cuts, which are routinely ignored or somehow unmagical because they were put through by Democrats, did the rest. And yeah, we’ve extended UI benefits (good idea), extended the payroll tax cut (also), extended the full Bush tax cuts (ok, short term) and the result is a lot more debt.

We do need to break the cycle of spending without regard to revenue. I, for one, want “tax and spend” over “borrow and spend.” Right now, we’re continuing borrow and spend but it’s understandable given the economic circumstances. Context matters.

If the economy continues to improve, it will be time to shift policy as well.

@john personna:

I’m not sure I understand your point. The raw numbers show that deficit spending has skyrocketed under Obama. I don’t find it particularly damning given the circumstances. But, yes, the stimulus accounts for a lot of money. And Obama doubled down on Afghanistan and merely followed the Bush plan for exiting Iraq, so it’s not like he saved us any money on that front.

@James Joyner:

Separate spending increase from revenue shortfall, James.

You can do it.

(If the numbers at Economist’s View are wrong that’s one thing, but if they are correct and people on the right just can’t face them, that’s another.)

@john personna:

Do you think he can? He’s fixated on the stimulus which was pretty small potatoes. The stimulus was around 800 billion with about 700 billion spread over four years (and nearly a third of it was tax cuts). So average total expenditures have been 175 billion a year while deficits have been averaging around 1.3 billion. Tax revenues are running at around 15% of GDP and have been for three years in an underperforming economy when they should be around 20%. Forecast GDP for fiscal 12 is around 15.5 trillion as best I recall so 20% would produce revenues of around 3.1 trillion giving a deficit of under 500 million. Not that I’m suggesting we should try to bump taxes back to 20% of GDP immediately but indicates the importance of revenue in the deficit equation.

Things like this are why the talk about debt end up making zero sense.

A president comes into office and on the first day he has to work with a budget that has a projected 1.3 trillion dollar deficit. With almost a trillion of that being structural. Then we get shallow analysis about how he’s been running trillion dollar deficits with some vague equivalence BS about tax cuts and spending. I know it hurts people’s brains to think about political issues in more than just stereotypes of the parties, but that’s the problem.

The real story is debt as a percentage of GDP (insomuch as the debt matters, raw numbers are still stupid) and what’s being done about the things that cause the debt outlook to be so bad. And i’ll give you a hint for the latter… it starts with health and ends in care.

@Ben Wolf:

SD might not be interested in reading your suggestions, but I am. Any chance you could offer some macro econ 101 texts (preferably written for neophytes)…

@mattb: A little dense, but short and free:

http://moslereconomics.com/mandatory-readings/soft-currency-economics/

This is what separates MR/MMT from schools like the post-keynesians. It’s a hard look at how the financial system, the Fed and Treasury, interest rates and public debt function. It’s empirical without the politics and theory which distort so much economic analysis. I’d suggest reading this first and when you’re comfortable with the concepts, move on to Abba Learner and Wynne Godley who pioneered game-changing work in sectoral balances. A fine non-academic and very readable summary of these mens’ aggregate work can be found here and also has the virtue of being free:

http://pragcap.com/resources/understanding-modern-monetary-system

The problem with most mainstream and heterodox schools of economic thought is they neglect or outright ignore the banking system. It’s akin to a neurosurgeon who didn’t bother to study the brain, in my opinion. QE was supposed to stimulate demand according to monetarist and neo-liberal economic theory, but anyone who had read and understood Soft Currency Economics was aware the money had no channel into the real economy. The banking system simply wasn’t capable of doing what theorists wanted it to do.

@mattb

What he means is he’s just recommended some crank economic books to you. You can pick up a used copy of Krugman’s standard economic textbook for around 50 bucks (and Krugman is fully aware of the role of the banking system in economic management).

http://www.amazon.com/Economics-Paul-Krugman/dp/0716771586/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1332351293&sr=1-1

@mattb: You can decide for yourself. Joe finds it easy to insult and slander the work of people he’s never bothered to understand, and that’s unfortunate but typical of him. Krugman does in fact not have a thorough understanding of the banking system because it isn’t an area he’s ever studied. He’s maintained for years that the money multiplier exists even thought the Federal Reserve itself has acknowledged there’s no empirical evidence for it. But by joe’s definition Krugman must be a crank too, because he’s also referenced sectoral balances:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/30/eurozone-problems/

@Ben Wolf:

Indeed you can decide for yourself. I’ll just say this. The number of economists who take MMT seriously is roughly similar to the number of aeronautical engineers who take alien abduction seriously so I’m not going to waste time tilting at windmills. As for Krugman’s alleged lack of understanding of the banking system I’ll let this extract from his Wiki biog speak for itself (his paper on currency crises is his second most cited). It all speaks to massive authority but I’ve highlighted a couple of areas specifically related to banking and international finance.

Krugman earned his B.A. in economics from Yale University summa cum laude in 1974 and his PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1977. While at MIT he was part of a small group of MIT students sent to work for the Central Bank of Portugal for three months in summer 1976, in the chaotic aftermath of the Carnation Revolution.[30] From 1982 to 1983, he spent a year working at the Reagan White House as a staff member of the Council of Economic Advisers. He taught at Yale University, MIT, UC Berkeley, the London School of Economics, and Stanford University before joining Princeton University in 2000 as professor of economics and international affairs. He is also currently a centenary professor at the London School of Economics, and a member of the Group of Thirty international economic body. He has been a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research since 1979.[31] Most recently, Krugman was President of the Eastern Economic Association.

Paul Krugman has written extensively on international economics, including international trade, economic geography, and international finance. The Research Papers in Economics project ranked him as the 14th most influential economist in the world as of March 2011 based on his academic contributions.[12] Krugman’s International Economics: Theory and Policy, co-authored with Maurice Obstfeld, is a standard undergraduate textbook on international economics.[32] He is also co-author, with Robin Wells, of an undergraduate economics text which he says was strongly inspired by the first edition of Paul Samuelson’s classic textbook.[33] Krugman also writes on economic topics for the general public, sometimes on international economic topics but also on income distribution and public policy.

The Nobel Prize Committee stated that Krugman’s main contribution is his analysis of the impact of economies of scale, combined with the assumption that consumers appreciate diversity, on international trade and on the location of economic activity.[9] The importance of spatial issues in economics has been enhanced by Krugman’s ability to popularize this complicated theory with the help of easy-to-read books and state-of-the-art syntheses. “Krugman was beyond doubt the key player in ‘placing geographical analysis squarely in the economic mainstream’ … and in conferring it the central role it now assumes.”[34]

In 1978, Krugman wrote The Theory of Interstellar Trade, a tongue-in-cheek essay on computing interest rates on goods in transit near the speed of light. He says he wrote it to cheer himself up when he was “an oppressed assistant professor”.[35]

[edit] New trade theoryPrior to Krugman’s work, trade theory (see David Ricardo and Hecksher-Ohlin model) emphasized trade based on the comparative advantage of countries with very different characteristics, such as a country with a high agricultural productivity trading agricultural products for industrial products from a country with a high industrial productivity. However, in the 20th century, an ever larger share of trade occurred between countries with very similar characteristics, which is difficult to explain by comparative advantage. Krugman’s explanation of trade between similar countries was proposed in a 1979 paper in the Journal of International Economics, and involves two key assumptions: that consumers prefer a diverse choice of brands, and that production favors economies of scale.[36] Consumers’ preference for diversity explains the survival of different versions of cars like Volvo and BMW.[37] But because of economies of scale, it is not profitable to spread the production of Volvos all over the world; instead, it is concentrated in a few factories and therefore in a few countries (or maybe just one). This logic explains how each country may specialize in producing a few brands of any given type of product, instead of specializing in different types of products.

Many models of international trade now follow Krugman’s lead, incorporating economies of scale in production and a preference for diversity in consumption.[9] This way of modeling trade has come to be called New Trade Theory.[34]

Krugman’s theory also took into account transportation costs, a key feature in producing the “home market effect”, which would later feature in his work on the new economic geography. The home market effect “states that, ceteris paribus, the country with the larger demand for a good shall, at equilibrium, produce a more than proportionate share of that good and be a net exporter of it.”[34] The home market effect was an unexpected result, and Krugman initially questioned it, but ultimately concluded that the mathematics of the model were correct.[34]

When there are economies of scale in production, it is possible that countries may become ‘locked in’ to disadvantageous patterns of trade.[38] Nonetheless, trade remains beneficial in general, even between similar countries, because it permits firms to save on costs by producing at a larger, more efficient scale, and because it increases the range of brands available and sharpens the competition between firms.[39] Krugman has usually been supportive of free trade and globalization.[40][41] He has also been critical of industrial policy, which New Trade Theory suggests might offer nations rent-seeking advantages if “strategic industries” can be identified, saying it’s not clear that such identification can be done accurately enough to matter.[42]

[edit] New economic geographyIt took an interval of eleven years, but ultimately Krugman’s work on New Trade Theory (NTT) converged to what is usually called the “new economic geography” (NEG), which Krugman began to develop in a seminal 1991 paper in the Journal of Political Economy.[43] In Krugman’s own words, the passage from NTT to NEG was “obvious in retrospect; but it certainly took me a while to see it. … The only good news was that nobody else picked up that $100 bill lying on the sidewalk in the interim.”[44] This would become Krugman’s most-cited academic paper: by early 2009, it had 857 citations, more than double his second-ranked paper.[34] Krugman called the paper “the love of my life in academic work.”[45]

The “home market effect” that Krugman discovered in NTT also features in NEG, which interprets agglomeration “as the outcome of the interaction of increasing returns, trade costs and factor price differences.”[34] If trade is largely shaped by economies of scale, as Krugman’s trade theory argues, then those economic regions with most production will be more profitable and will therefore attract even more production. That is, NTT implies that instead of spreading out evenly around the world, production will tend to concentrate in a few countries, regions, or cities, which will become densely populated but will also have higher levels of income.[9][11]

International finance

Krugman has also been influential in the field of international finance. As a graduate student, Krugman visited the Federal Reserve Board, where Stephen Salant and Dale Henderson were completing their discussion paper on speculative attacks in the gold market. Krugman adapted their model for the foreign exchange market, resulting in a 1979 paper on currency crises in the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, which showed that fixed exchange rate regimes are unlikely to end smoothly: instead, they end in a sudden speculative attack.[46] Krugman’s paper is considered one of the main contributions to the ‘first generation’ of currency crisis models,[47][48] and it is his second-most-cited paper (457 citations as of early 2009).[34]

@Brummagem Joe: @Brummagem Joe: Joe, read before you quote. Your reference shows Krugman has done work in economic demographics and the FX market, not the banking system. Otherwise he wouldn’t have acknowledged last year that he didn’t understand why interest rates hadn’t spiked due to large deficits, he would understand why the money multiplier is a myth, and he would understand the difference between vertical and horizontal transactions. He’s been moving in the right direction, but this isn’t his field, nor should he be expected to understand an area he hasn’t devoted a lot of time to. No one can be an expert in everything.

@Ben Wolf:

I wonder whether you can read. There are specific references to him spending time working in two central banks and he’s an aknowledged world authority on currencies and international finance. That you think this status possible without having complete understanding of how banking systems function speaks volumes about how seriously you are to be taken.

There is only one issue here, and it’s not being addressed by the Democrats. The US currently borrows 40 cents of every dollar it spends. My personal budget cannot operate that way, and neither can yours. As for the US, it cannot operate its budget that way either. Sooner or later – most likely sooner, and in the next 2-3 years – this house of cards will come tumbling down. So, at this it’s totally irrelevant who’s responsible for spending all this money and running up the debt. Truth be told: both parties are equally responsible for the fix we’re in. The only pertient issue now is which party has a plan – or plans – to begin reducing this debt RIGHT NOW. There simply is no more time to waste on balancing the budget. And it’s going to hurt everybody – repeat, EVERYBODY – quite badly. The dance is over and it’s now time to pay the band, folks.

@Only One Issue Here:

Wow….you can borrow millions of dollars for 10 years at around 2.2 interest. You’ll have to tell me where I can pick up these loans.

Considering this house of cards has been going on for over 30 years, your prediction doesn’t seem very prescient…

Because of the 2008 crash of the housing and financial markets it was virtually guaranteed that ANY president would have to seriously consider major deficit spending to support aggregate demand. Trillions of dollars in income and wealth was vaporized in the crash.

the question is whether we have the GDP and tax base to support the debt we have – we do.