Initiative To Split California Into Three States Blocked From Appearing On Ballot

An initiative that would have purported to split California into three separate states has been barred by the California Supreme Court from appearing on the November ballot.

The California Supreme Court has blocked a measure that would allow voters to vote on a plan that would split the state into three states from appearing on the November ballot:

The state Supreme Court decided Wednesday that California will remain intact geographically, at least for now, while it decides whether the voters can consider a proposal to divide the Golden State into three new states.

The three-state initiative, Proposition 9, had gathered enough signatures to qualify for the November ballot. Nine days after opponents filed suit, the court issued a unanimous order removing the measure from the ballot and ordering further legal arguments on whether it should be placed on another ballot in 2020 or struck down altogether.

The court said it usually allows ballot measures to go to the voters before considering constitutional challenges. But in this case, the six justices said, “significant questions regarding the proposition’s validity” and the “potential harm” of allowing a public vote before those questions are resolved “outweighs the potential harm in delaying the proposition to a future election.”

Those questions include whether California voters’ broad authority to enact laws by initiative, established in 1911, includes the power to break up the state, and in the process abolish its Constitution and existing laws, to be replaced by lawmaking bodies in three future states.

The narrower legal issue is whether Prop. 9, drafted as a change in the laws that define California’s boundaries, would actually amount to a “revision” of the state Constitution. That cannot be done by initiative, but instead requires approval by two-thirds of both houses of the Legislature to be placed on the ballot.

“We believe it is clear that a ballot initiative may not revise the Constitution by making changes in the basic framework of government,” said Carlyle Hall, a lawyer for opponents who sued to take Prop. 9 off the ballot. “And there can be no greater change in our framework of government than the total abolition of our existing Constitution.”

Howard Penn, executive director of the Planning and Conservation League, lead plaintiff in the lawsuit, said Prop. 9 would have caused “chaos in our public services including safeguarding our environment … all to satisfy the whims of one billionaire.”

The billionaire is Bay Area venture capitalist Tim Draper, who drafted Prop. 9, qualified it for the ballot and has represented himself without a lawyer in the court proceedings. Draper argued that California has become ungovernable — its taxes too high, its schools and public services in disrepair, its 39 million-plus residents far too numerous to be represented democratically by 120 elected legislators

He reacted indignantly to the court order.

“Apparently, the insiders are in cahoots and the establishment doesn’t want to find out how many people don’t like the way California is being governed,” Draper said in a statement. He said the six justices “probably would have lost their jobs” under the three-state plan.

“The whole point of the (state’s) initiative process,” he added, “was to be set up as a protection from a government that was no longer representing its people. Now that protection has been corrupted.”

The Court’s ruling is relatively short:

Time constraints require the court to decide immediately whether to permit Proposition 9 to be placed on the November 6, 2018, ballot pending final resolution of this matter. Although our past decisions establish that it is usually more appropriate to review challenges to ballot propositions or initiative measures after an election (Costa v. Superior Court (2006) 37 Cal.4th 986, 1005), we have also made clear that in some instances, when a substantial question has been raised regarding the proposition’s validity and the “hardships from permitting an invalid measure to remain on the ballot” outweigh the harm potentially posed by “delaying a proposition to a future election, ” it may be appropriate to review a proposed measure before it is placed on the ballot. (Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Assn. v. Padilla (2016) 62 Cal.4th 486, 494; see also id., at pp. 496-497; accord, American Federation of Labor v. Eu (1984) 36 Cal.3d 687, 697.) Because significant questions have been raised regarding the proposition’s validity, and because we conclude that the potential harm in permitting the measure to remain on the ballot outweighs the potential harm in delaying the proposition to a future election, respondent Alex Padilla, as Secretary of State of the State of California, is directed to refrain from placing Proposition 9 on the November 6, 2018, ballot. Both respondent Padilla and real party in interest Timothy Draper are ordered to show cause before this court, when the above matter is called on calendar, why the relief sought by petitioner, Planning and Conservation League, should not be granted. The returns of respondent and real party in interest are to be served and filed on or before Monday, August 20, 2018. Petitioner is ordered to serve and file its reply within 30 days of the timely-filed returns.

Proposition Nine isn’t the first attempt in recent years to break California up into separate states; in fact, it is an idea that goes back several decades at least. In an effort that has roots in political movements dating back to the 19th Century, for example, a number of counties in Northern California have at various times put forward plans that would have created a new state called “Jefferson” in what is now Northern California. The most well-organized of those efforts occurred in late 1941 but it suffered from a number of political and other setbacks and ultimately ended up being sidelined after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. (Source) More recently, the same Silicon Valley billionaire who is behind Proposition Nine was also behind another proposal that would have split California into six separate states. That measure, though, failed to gain enough signatures to get on the ballot in 2014 and largely died in the aftermath of that failure. This latest proposal from Draper, then, is just another version of a “divide California” movement that has been going on for some time now.

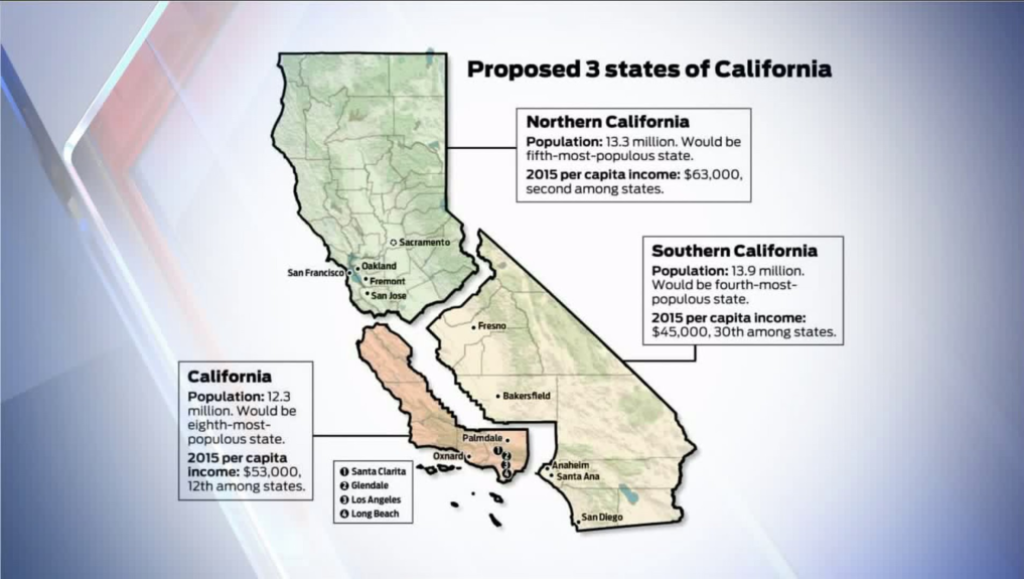

The new proposition would have created three new states — Southern California, which would consist largely of an area running from San Diego to the eastern border with Arizona and Nevada and then north to a point north of Fresno, California, which would run along the Pacific Coast from Los Angeles to Monterey, and Northern California, which would encompass the remainder of the state from Santa Cruz north to the border with Oregon. If approved, the plan claims that the proposal would then be sent to Congress, which would have to approve or disapprove of the plan. Politically, this would mean that there would be four new Senators representing the two “new” states along with the remaining rump state of California and would divide the states Congressional Districts and Electoral College votes accordingly. Based on projections, it appears that California and Northern California would remain more or less dominated by the Democratic Party while the proposed state of Southern California would likely swing Republican or at the very least be a far more competitive state for the GOP than California is at the present time. On a final note, it would be up to legislators from the “original” California as well as the governments of the three new states to find a way to divide the resources of the state, including such contentious issues as access to water supplies, which is already a huge conflict between the farming community and cities such as Los Angeles.

As James Joyner noted back in June, the measure received enough signatures to appear on the ballot in November, but it was clear from the beginning that it faced an uphill battle both in the Courts and in the court of public opinion. Politically, for example, a SurveyUSA poll released in April when the signature drive for the referendum was still going on found that 72% of those polled opposed the idea of dividing California while only 17% said they supported it. This suggests that the initiative would have failed had it been allowed to remain on the ballot. This was similar to the reception that the aforementioned “Six Californias” proposal received when it was being proposed back in 2014.

As a matter of law, it was also unclear whether the initiative was even proper to begin with, both because of the state law issues that formed the basis for the state Supreme Court’s ruling and for other reasons rooted in the U.S. Constitution. Essentially, the state law argument against the proposal is that California law forbids revisions to the state Constitution from being adopted via the referendum process and that a proposal that would effectively rip up the current California Constitution is most assuredly a revision to the Constitution. Therefore, the state Supreme Court ruled, the matter cannot appear on the state ballot.

In addition to those state law arguments, the measure also appears to run afoul of the provisions of the U.S. Constitution dealing with the creation of new states. That provision, set forth in Article IV Section 3 Clause One of the Constitution provides that “no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.” At the very least, it is not clear that approval via a referendum would be considered approval by the “legislature” of California, however the fact that the Constitution clearly states “legislature” suggests that only the state representatives of the affected state, which in this case would be the entire state of California as we know it today, would be the proper parties to approve a proposal to break the state up as this plan proposes. In addition to the California legislature, the measure would also have to be approved by legislatures representing each of the three proposed states and by Congress. The odds of this happening are, of course, somewhere between slim and none.

California would go from 2 Democratic Senators, to 4 Dems and 2 Republicans, a net gain of 2. So obviously this is going nowhere. We’re back to Missouri Compromise days here, no new free states unless there are slave states for balance.

Aren’t we tired of meddling rich guys playing politics yet?

@Michael Reynolds:

I don’t live in California but the whole idea seems kind of silly to me. Breaking up the state isn’t going to solve any of the long-term problems the state has, and it’s likely to create a whole host of new ones.

As I note in the post, one of the biggest would seem to me to be the battle over water supplies between “Southern California” and “California.”

@Doug Mataconis: As I note in the post, one of the biggest would seem to me to be the battle over water supplies between “Southern California” and “California.” Bingo. California in the not so distant future will be a declining state unless the western drought eases. To be reliant on resources not really in the state’s control will be a severe weakness.

@Michael Reynolds:

How? My impression is that the net gain for the Democrats will be zero, if both D and R will have +2 senators than before.

Mr. Prosser,

Of course at that point they could look to desalination of ocean water. It’s a costly process but it may be the only one that will work long term.

Off-topic but related (and Doug might be interested in this), but the Michigan Supreme Court is accepting a challenge to our gerrymandering ballot initiative. This is totally screwed up, since we elected those judges and 5 of the 7 are Republicans who benefited from the very gerrymandering they might rule on.

@Miguel Madeira:

Never, ever trust me where numbers are concerned.

How about reuniting california to Baja California?

Sure, there’d be problems, and you’d change countries, but you’d be 100% Trump free! 😉

@Doug Mataconis:

Indeed, the politics of water in California has always been very important, and that will never NOT be the case.

The biggest split in CA is the Blue State/Red State divide within CA: between Blue State residents on the coast (from Long Beach/LA up to San Francisco) and Red State residents of the Central Valley and mountain areas to the east. of the state’s 39M population, about 26 million people live in metro Bay Area or metro LA-Long Beach. Metro San Diego used to be strongly Republican, but is is almost purple now.

@Miguel Madeira:

Current California has 2 Democratic senators. Rump California would retain those two. One of the two new states would almost certainly elect 2 Democratic senators, while the other one could go either way.

Prior: 2 Dem senators.

Post: 4 Dem senators and possibly 2 Republican ones. It’s a net gain of two senators for the Dems, BUT it would set the halfway point in the revised Senate at 52. Using the current Senate, it would result in R 53 / D 51. The best case scenario for Republicans is preservation of the status quo. Worst case is all three new states go Dem, which would result in R 51 / D 53, which would shift control to the Dems. Republicans will never agree to it for that reason.

There have been proposals to split California for 100 years, usually at the Tehachapi Mountains and water has been the big objection since ~1970. The Los Angeles water supply gets confusing on whether it is just the City vice the entire County, as the City also has the Los Angeles Aqueduct from the Eastern Sierras (Owens River). Averaging numbers to account for droughts and changes (environmental laws) the Los Angeles area gets about 10% of its water locally, and very roughly about a third each from the California State Water Project (Northern California – battles over farming and environmental uses), Los Angeles Aqueduct (only taking half as much as in the past for environmental remediation, and the Colorado River Aqueduct (conflicts with NV and AZ and Mexico).

I see the small size of the California legislature as an issue, similar to previous posts on OTB about the size of the US Congress. As stated in the article CA has 120 legislators (80 in Assembly, 40 Senate) and a population of 39M = 3 Representatives/million. For comparison with a few other states:

WA 147/7.4M = 20 Representatives/million.

VA 140/8.4M = 16 Representatives/million

NY 213/20M = 10.6 Representatives/million

By my calculation the net gain in Democratic senators going from 2D to 4D + 2 R is zero. Before you were +2D, and after, you are +2D. Because 4-2 = 2.

The gross gain in Democratic Senators is 2. Also the gross gain in Republican Senators is 2. But the net gain(loss) in both is zero. That’s my understanding of what “net” means.

When financial institutions report their earnings to me “gross of fees”, it means they haven’t subtracted fees. And when it’s “net of fees” (something that was hard to get my hands on, it turns out), they have subtracted their fees. Of course, the latter is the much more interesting number to me.

Draper’s claims as to why this split would result in better governance makes no sense at all. Which is why many of us suspect he isn’t being transparent about his motives. He could just be kind of monomaniacal, though.

Glory be and saints be praised!

@Michael Reynolds:

Draper’s “defense” of his initiative referrenced the Pico Act of 1859, which was an attempt to create a slave state in Southern California.

Dividing California would create one liberal state and two or three swing states. That would have lots of political implications, specially on close elections, and it would increase the chance of someone being elected president while winning the EC and losing the Popular vote.

@Kari Q: Boom!

Those lines look a lot like that San Andreas fault line.

Is that some kind of prediction?