Is All Politics Presidential?

Have gubernatorial elections become more nationalized?

The long-awaited relaunch of FiveThirtyEight has finally happened. Nate Silver outlines the manifesto of the much-expanded site here.

Among the first pieces on the politics side is Georgetown political scientist Dan Hopkins‘ “All Politics Is Presidential.” The hook:

Thirty-eight states will choose governors this November. These states are home to 79 percent of the total U.S. population. They face a range of challenges, from too few jobs to too little water, that are as varied as the candidates they’re voting for. Some of the candidates are long-time incumbents, others are new to politics. Some are quite liberal, others not so much. Some served as governor back in the 1970s, others were born in that decade.

But despite those differences, the candidates for governor in 2014 share something important in common: From Colorado to Florida, voters are likely to see them as Democrats and Republicans first, and as individual candidates a distant second. In recent years, gubernatorial elections have become increasingly nationalized, to the point where voting patterns in these races bear a striking resemblance to those in presidential races. If we look at all sitting governors, just 15 of the 50 lead states that were won by the other party in the last presidential election. That means just 30 percent of states split their votes.

Emphasis mine. The natural reaction is that this isn’t surprising or new. But it’s certainly the latter: “As recently as 1995, the figure was 44 percent, as Republicans were still competitive throughout the northeast.”

The analysis that follows, though, is somewhat problematic. Hopkins does a long-term analysis of voting patterns outside the South, which he excludes because of its “one-party politics . . . until the 1960s.”

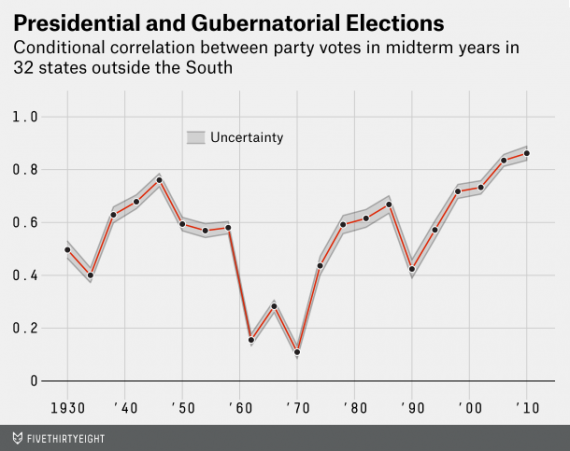

In the graph above, we see the relationship for midterm elections like 2010, and in the graph below we see it for presidential years like 2012.1 For gubernatorial elections held in midterm years, the predictive power of presidential voting rose during the 1940s, fell sharply in the early 1960s and then began to rebound in the 1970s. In 2010, it peaked: That year’s gubernatorial elections were the most nationalized since the New Deal. The counties that were the most strongly Republican in 2008 were the most strongly Republican in 2010. To a surprising extent, 2010’s gubernatorial races looked like a rematch of 2008’s presidential race, albeit with much higher baseline GOP support.

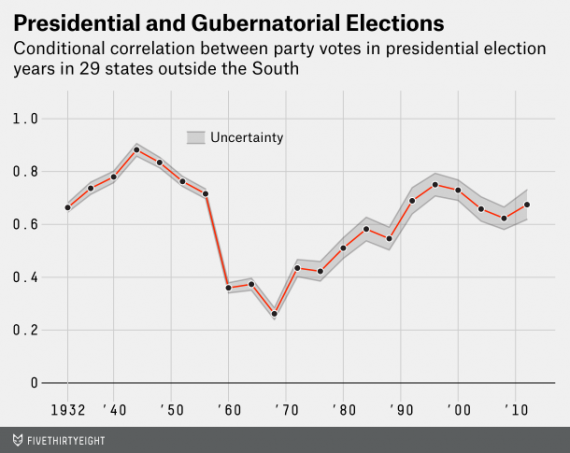

Hopkins finds similar, if not quite as robust, results in presidential election years:

You can see that nationalization has been rising since the 1970s in these on-cycle elections, too, and that an increasingly close relationship between presidential and gubernatorial voting has tapered off only slightly in recent years. Comparing the left and right graphs, we reach a surprising conclusion: The nationalization of the gubernatorial vote appears even stronger today in midterm elections, where the presidential candidates don’t appear on the same ballot.

But excluding the South skews the results, since it depresses the extent to which gubernatorial and presidential politics were correlated in the early period and exaggerates the extent to which it’s correlated now. As Hopkins notes, the South was lockstep Democratic for decades, at both the presidential and gubernatorial level. Now, though, there are several Democratic governors, even in states that voted Republican in 2008 and 2012. Furthermore, as Hopkins notes in his narrative, the northeast has now become solidly Democratic.

Hopkins explains his nationalization thesis on the simple basis that people now care more about presidents than governors:

In a recent survey through GfK’s Knowledge Panel, which recruits adults from across the U.S. to take online surveys, I asked a national sample whether they followed the president, their state’s governor or their local executive most closely. Eighty percent named the president, while just 12 percent named their governor. Later in the survey, I asked which of those positions had the most impact on the respondents’ day-to-day lives. The answers were quite different, with 46 percent naming the president and 31 percent naming their governor. So as voters, we know that governors have significant authority (state and local governments account for 47 cents of every dollar spent by governments in the U.S.) — but we nonetheless keep our gaze fixed on the presidency.

But Hopkins provides no evidence that the degree to which this is so has been increasing. I’d guess that this has been true all of my lifetime, if not going back to FDR’s day, when the modern presidency emerged. Since the New Deal and especially the onset of World War II, the president has been in charge of setting the national agenda. This coincided with the emergence of mass communications, of which the president has always been the central figure. Governors have to go a long way, indeed, to get that sort of coverage even locally.

Furthermore, if the argument is that the president sucking all the political oxygen out of the room makes it hard for governors to create their own branding, then it would seem logical that there would be a closer, not lesser, correlation during presidential cycles. In addition to the traditional “coattail effect,” there’s less room for gubernatorial candidates to get in a word edgewise.

I have the same IP lawyer as Nate Silver, so I’m sending him a back-channel request to just tell me who the hell is going to win in 2016. We could get it over with right now. Imagine the money we’d save. Imagine the agita we’d avoid.

Just tell us, nerd, or we’ll give you a swirlie!

The site is going to be huge. Someone over at ESPN is pretty smart.

@michael reynolds: Ha. I don’t think he’s got the needed data to make predictions at this point but, yeah, I think the site will be great and look forward to the launch of the new Ezra Klein/Matt Yglesias project. Getting a lot of smart nerds together and giving them the resources to put out good work should be a good business model. Considering that Silver and Klein were drawing a significant chunk of the traffic at NYT and WaPo, respectively, on their own says something.

I’m out here in Oregon. Oregonians are not as liberal as people think but a couple of decades ago the religious right got control of the Republican party here and with the exception of Senator Gordon Smith have not won a statewide office since. Like much of the West Oregon tends to be Libertarian and that includes both Democrats and Republicans but there is still a certain empathy for those in need. The conservatives in the Eastern two thirds of the state share a respect and concern for the environment with the “liberals” in the Portland area.

There are very few swing voters in 2014 and the number of swing voters will continue to decline given the demographic trends in the U.S. If all politics is presidential politics, then the U.S. will be a one party state sooner than 2028.

As news has become more and more national so has politics.

So…correlation of states outside the South. Why not just do the correlation of states outside the exceptions, and get to 1.0?

I’d argue it was mass communication more than anything special about the presidents. The presidents are really just the [figure]heads of their parties. If anything, party branding has become more important, with less room for politicians to wiggle inside it as the various editorial writers impose their own meaning on what “Democrat” and “Republican” mean.

It’d be really neat if we could work out something closer to a parliamentary system where you have five or six parties (as you could easily break the Democrats and Republicans into six sub-parties if you had to) that form legislative coalitions. Elections for House Speaker would actually be interesting.

Does the image for this article remind anyone of an album cover? http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/3/39/WishYouWereHere-300.jpg