The Euro Zone: Join, Or Die

There may be only one solution to saving the Euro.

The head of the European Central Bank said this week that the Euro Zone is unsustainable under current conditions, and seemed to hint pretty strongly that the only way it can survive is if it becomes far more centralized than most Europeans seem comfortable with at this time:

U.S. and European officials, who just weeks ago seemed to be getting a handle on the euro zone’s financial crisis, are now scrambling to prevent a new round of problems from pulling down some of Europe’s largest economies.

European Central Bank President Mario Draghi warned in Brussels on Thursday that he considered the euro zone’s current structure “unsustainable,” and said the region’s governments must surrender far more budget and regulatory power to a central authority if the currency union is to be saved.

His comments — and an intense week of high-level lobbying by U.S. officials — come amid a worldwide swoon on stock markets, a flight by investors to the safe haven of U.S. and German bonds, and a growing concern that problems in Spain’s banking sector may force the euro zone’s fourth-largest economy to seek a costly bailout. Major U.S. stock market indexes were down 6 percent in May and the euro is trading near a two-year low against the dollar.

(…)

A developing recession in Europe is part of the reason for the renewed sense of tension. The economies of major nations including Italy and Spain are shrinking, while France’s has stagnated. The wider global

economy could be losing steam as well. With economic activity in China slowing, authorities there have recently tried to give it a boost by increasing government spending. As the global recovery stalls, crude oil prices have fallen 20 percent in the past two months.On Friday, the U.S. Labor Department will release its monthly employment report, offering evidence of whether the American economy is continuing to buck the global slowdown or is being held back by global trends.

A sense of political drift in Europe, meanwhile, is taking hold. This is reigniting concern that the euro region’s leaders may not act fast enough to prevent investors from abandoning countries such as Spain and Italy for fear they may default on their bonds or, more dramatically, drop the euro.

Political uncertainty has been stoked by the current political stalemate in Greece. With its leading political parties deadlocked ahead of June 17 elections, the country’s current bailout program is being pushed off track, raising the risk that Greece may become the first country to exit the euro and fracture the euro currency union.

New leaders in Spain, Italy and, more recently, France, meanwhile, are pressuring German Chancellor Angela Merkel to put even more of her country’s financial weight behind measures needed to prop up weakened European governments and banks.

The debate is increasingly focused on the possibility that the Spanish government may not be able to afford the costs of a banking-system rescue.

In recent weeks, European officials, the International Monetary Fund and others have urged that an existing European bailout fund be used to pump money directly into Spanish banks. At the moment, the Spanish government would have to borrow money to bail out the banks, and this would increase its own debt, aggravating concerns about Spain’s financial health.

German officials are opposed to providing the bailout fund with the flexibility to help banks directly.

In Brussels on Thursday, Mario Monti, Italy’s prime minister, said Germany was putting the goal of a more integrated Europe at risk by its “lack of promptness” in accepting the change.

Draghi, a critical voice in the discussion as head of the central bank used by the 17 nations, said Europe needed to do more to back its banking system. At the same time, he criticized the slow response of Spanish officials in dealing with their banking crisis.

Draghi has a point, of course. Right now, the Euro Zone is a collection of seventeen nations which have some things in comment, but many differences. Most importantly, though, it is a collection of seventeen sovereign nations, each of them with leaders that must respond to their constituencies and the economic conditions in their own countries. Outside of the fact that they have a common currency, the amount of actual coordination between these nations on important economic issues is rather minimal, and the ability of any nation or group of nations to compel consensus, or even collective action of any kind is rather minimal. The European Central Bank plays that role to some extent, of course, but as we’ve seen in Greece, and as we are apparently now seeing in Spain, there isn’t much the ECB can do to force the banks in a sovereign nation to behave responsibly, and there’s next to nothing it can do to force the governments of those nations to do so.

Ed Morrissey put it very well in a post about this whole issue the other day:

Europe has a reason for the disunity, which goes to the core of their experiment: multiple sovereign nations managing a single currency. Germans end up having to suffer the consequences of irresponsibility in Greece, Spain, and France without having any real political power to prevent or punish it, short of pulling out of the euro. That has always been the rot at the center of the euro, and it was just a matter of time until it became a critical problem. The only way the euro would work in the long run would have been a federalization of Europe into one sovereign entity, an outcome that its peoples clearly do not want and which European language and cultural barriers wouldn’t allow even if popular sentiment supported unification initially. The UK looks like the most brilliant nation in Europe for its longstanding and prescient Euro skepticism.

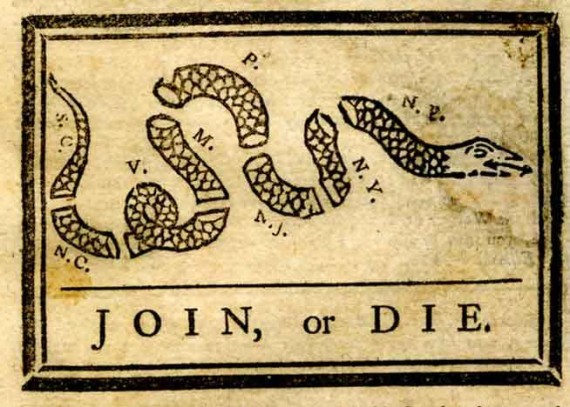

In the early days of the Revolutionary Era in what were then Britain’s colonies in North America, Benjamin Franklin penned a political cartoon that became popular among those urging collective action by the colonies to defend their interest, it’s title was “Join, Or Die.” History also says that, at the Second Continental Congress, where the Declaration Of Independence was signed, Franklin said to those assembled, “We must, indeed, all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.” The point of both of these statements, the second of which may be apocryphal, is that the colonies would only succeed in their struggle against the British, and indeed after independence, if they did it as one united nation.

That, I think, is the problem that the Euro Zone faces and has faced from the beginning. You can’t have a common currency without having a common fiscal policy, and you cannot have a common fiscal policy when each of your members is a political sovereign in its own right. The reasons the Euro Zone isn’t working aren’t really all that different from the reasons that the Articles of Confederation didn’t work. In both cases, you have an entity that purports to be a political authority while in reality it is merely a shell that has next to no control over its members and little ability to set “national” policy on issues that matter. The national “legislature” in both cases is mostly a joke, and in both cases the central authority has little ability to stop member states from taking actions that harm the “nation” as a whole. It is, in the end, a recipe for disaster.

America solved its problems by starting over again and drafting a new governing document that placed much more authority in the hands of a central government. It’s unlikely that that can or will happen in Europe today. As it is, there is tremendous resistance to the idea of a centralized European state among the people that live within its prospective borders, and one of the continents most important nations still resists even the idea of becoming part of the Euro (a smart decision, in retrospect). It’s possible that Europe’s elites could come to an agreement about a new treaty that would place much more authority in the hands of Brussels and the ECB, but it seems unlikely that such an agreement would receive popular approval. The difficulties that the proponents of the Constitution faced in ratification in 1787-88 would pale by comparison to what Europe would see in such a situation, I submit.

That would seem to leave Europe with very few options. Dumping the Euro completely would be painful, and a tremendous setback to the entire idea of European unity, but unless the nations of the Euro Zone are all willing to surrender some of their sovereignty for the good of the collective enterprise, it may end up being inevitable.

I also have seen parallels over the years between the Euro Zone and early Colonial America… The colonies wanted to behave much like sovereign nations – printing their own currencies, making treaties with each other (and other nations), etc. etc. But to survive, they eventually had to cede ultimate sovereignty to a central government, and I agree that that’s what has to happen in Europe too.

However, I also believe that it will never, ever happen. If the EU could limp on in its current state for a couple of generations, then – maybe – Europeans might be willing to be a bit less tribal and more brotherly with each other. But I think the iron resolve of some countries (looking at you, France & Germany) to even _risk_ a little pain to salvage others (even if it’s from a mess they didn’t make themselves) just shows that they’re not ready to take that “Join” step, and would still rather “Die”. The adamant refusal of the Euro Central Bank to actually take on the duties and responsibilities of a “central bank” is an important bellwether for this discussion…

@legion: The difference between the US and the Euro zone is that Europe is made up of societies that are hundreds if not a thousand years old – very tribal. The US on the other hand was building a society from scratch at the same time it was building the union. Sure there were differences but not the tribalism we see in Europe.

There were a lot of people, including me, who thought the Euro was a really bad idea. History is proving us right.

@Ron Beasley:

Excellent points.

The other difference is that, by and large, the residents of the colonies at the time of the Revolutionary Era largely all shared a common history and common culture. Europe is the name of a continent that contains a plethora of nations that have developed their own histories and cultures and, indeed, have gone to war with each other as recently as just 70 years ago. Expecting unity to just happen under those circumstances was naive in the extreme.

Good blog post.

Ironically enough there actually is a very viable, fairly easy solution to this mess. Because pure power politics are involved, however, and because many European politicians are in bed with institutional bondholders, I would not hold my breath.

Place all the bad European banks and investment banks into receivership, similar to what the FDIC does over here when it takes over a bad bank. Cut away the bad debt and restructure and recapitalize the companies. Depositors are safe. Stockholders get wiped out. Bondholders either get wiped out or maybe pennies on the dollar. As it should be. When you lend money at spread there is a chance you’ll lose that money. European citizens should not be forced to make whole with public dollars those who took bad risks and who made bad investments.

Get the really bad Euro economies (PIIGS) out of the union. Retain the remainder. PIIGS either default or they devalue their individual legacy currencies to pay off their debts. Germany, Britain, France, etc., move forward without them.

Without debt restructuing and bondholders losing money, and without PIIGS being jettisoned from the union, the inevitable “solution” will be a structural and permanent malaise on a grand scale.

@Tsar Nicholas: Good comment – I think you nailed it. The Euro was always a project of the technocrats and bankers. They gambled and they lost and should really loose.

Absolutely right and exactly what should have happened to the Too Big To Fail banks in the US.

On the subject of resistance to the EU by local politicians and residents, I think a significant factor is the democratic deficit in European institutions; the real decision-making power has always rested with the political elites and their appointees, rather than the rather weak European Parliament. While that kind of set up might well have flourished even a century ago (as did the earlier similar set ups in the US), modern Europeans are used to the idea of democracy and government by consent rather than elite, and I think this is a not insignificant factor in the resistance to greater EU integration.

A federal Europe is possible but its something that you would have to introduce over a long period with gradual changes. A common currancy is one of the last things you might do.

Also, it would be very nice to get the imput of the people in how things are governed. It seems that the technocrats dislike having to listen to the mobile vulgus, as the Romans would say, in how things are run.

@Doug Mataconis: While it’s nearly impossible to separate language from culture a common language in the colonies was important. I see the Europeans are complaining about the fact that English and French are the languages that the Eurozone uses.

The ECB could simply be empowered to deal with the peripheral countries’ debt problems; it is after all the authorized currency issuer and cannot become insolvent. But the divisions in Europe are such even that relatively modest step seems nearly impossible. The sooner nations begin the exit process the better off they’ll be.

On the plus side our credit downgrade doesn’t seem to have hurt us, eh? Where else are you going to put your money?

Also on the plus side, I’ll bet the drachma and the peseta will have sweet exchange rates, so Mediterranean here I come.

No, there are bigger problems here. Germany, the so called power house of Europe, has a debt to GDP ratio of 80%. With exception of Italy, there is no considerable industries or commodities being exported to generate cash in the southern countries. Greece is basically a tax raven for merchant ships and a touristic destination, economically speaking, for instance. To make matters worse, France and Germany used all kinds of protectionist measures to block companies from these countries to build factories in the other Euro countries. Not that matter: the Euro makes wages in Southern Europe expensive, and companies like Nissan are building factories in Morocco, Turkey and other countries outside the Euro Zone.

By the way, note that Alaska and Hawaii have very high cost of living, and the same thing happens in other US territories that uses the dollar. Take out the Debt problem, and Puerto Rico and Greece faces similar problems, economically speaking.

All of the criticism about the failure of the Eurozone countries to make the compromises that are necessary to keep the Euro in tact seem to be premised on the notion that keeping the Euro in tact is in the best interest of the citizens of these various countries. I think that is clearly an unsettled issue.

Also, the comparison to the American colonies is inapt in that the unity of the colonies was necessary in order to ensure the liberty and physical security of the colonists. The same cannot be said about the liberty and physical security of the residents of the various European countries.

Monetary unions and/or using another’s currency are relatively new constructs. Argentina tried pegging to the US$ 20 years ago. It did them well for a few years. Ultimately awful, but would staying with the peso have been worse? Probably.

A few years ago Iceland was about to jump headfirst into the EU to get the stability of the Euro. Now there are calls to peg their currency to the Canadian Looney. Grass is always greener somewhere else. 30 currencies in Europe creates massive inefficiencies. So is the answer just one?

What started as a coal tariff regime between the Federal Republic of Germany and France is now the largest bureaucracy on earth.

There is no one simple solution.

@michael reynolds:

Outside of the Swiss, there really isn’t any safe haven for cash other than US Treasuries, and the Swiss don’t float enough debt to meet world demand.

@Richard Gardner:

The economic inefficiencies of a common currency was one of the biggest selling points emphasized by Euro proponents when the idea was first advanced, you may recall. It strikes me, though, that in an era of electronic transactions this isn’t as big a deal as it used to be. I can go to Canada, Mexico, or the Caribbean and use my Amex or Mastercard and the transaction is instantaneously converted to dollars once it appears on my statement. On the business side, when much payment is done via EFTs, the same thing happens.

Perhaps there is a logic in having the strong economies in Europe (Germany, France, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian countries come to mind but I’m just guessing at this admittedly) share a common currency, but the idea that there is enough in common between Germany and Greece or Spain for them to be united monetarily is kind of silly.

@Doug Mataconis: This is another example of the” bigger is better” myth. You eventually reach a point where an organization becomes so big and complex it can’t be managed and inefficiency actually begins in increase. Governments are certainly an example but so are large multi-national corporations. The too big to fail banks are an obvious example but it also applies to the likes of GE and Exon.

Look: Join or Die worked because “Die” was a real possibility. The colonies had to join together to stave off defeat in war.

The Euros simply aren’t facing that sort of threat. And thus they may decide (and may be correct to decide) that they’re better off busting the whole thing up.