Legendary Washington Post Editor Ben Bradlee Dies At 93

The passing of a true legend in American journalism.

Ben Bradlee, who as editor of The Washington Post editor presided over perhaps the most important political news story in American history, as well as a Vietnam War era confrontation with the Nixon Administration that led to one of the Supreme Court’s most important First Amendment rulings, and helped turn the newspaper he worked for from a local newspaper into a national and international paper of record on a par with The New York Times, has died at the age of 93:

Benjamin C. Bradlee, who presided over The Washington Post newsroom for 26 years and guided The Post’s transformation into one of the world’s leading newspapers, died Oct. 21 at his home in Washington of natural causes. He was 93.

From the moment he took over The Post newsroom in 1965, Mr. Bradlee sought to create an important newspaper that would go far beyond the traditional model of a metropolitan daily. He achieved that goal by combining compelling news stories based on aggressive reporting with engaging feature pieces of a kind previously associated with the best magazines. His charm and gift for leadership helped him hire and inspire a talented staff and eventually made him the most celebrated newspaper editor of his era.

The most compelling story of Mr. Bradlee’s tenure, almost certainly the one of greatest consequence, was Watergate, a political scandal touched off by The Post’s reporting that ended in the only resignation of a president in U.S. history.

But Mr. Bradlee’s most important decision, made with Katharine Graham, The Post’s publisher, may have been to print stories based on the Pentagon Papers, a secret Pentagon history of the Vietnam War. The Nixon administration went to court to try to quash those stories, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision of the New York Times and The Post to publish them.

President Obama recalled Mr. Bradlee’s legacy on Tuesday night in a statement that said: “For Benjamin Bradlee, journalism was more than a profession — it was a public good vital to our democracy. A true newspaperman, he transformed the Washington Post into one of the country’s finest newspapers, and with him at the helm, a growing army of reporters published the Pentagon Papers, exposed Watergate, and told stories that needed to be told — stories that helped us understand our world and one another a little bit better. The standard he set — a standard for honest, objective, meticulous reporting — encouraged so many others to enter the profession. And that standard is why, last year, I was proud to honor Ben with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Today, we offer our thoughts and prayers to Ben’s family, and all who were fortunate to share in what truly was a good life.”

The Post’s circulation nearly doubled while Mr. Bradlee was in charge of the newsroom — first as managing editor and then as executive editor — as did the size of its newsroom staff. And he gave the paper ambition.

Mr. Bradlee stationed correspondents around the globe, opened bureaus across the Washington region and from coast to coast in the United States, and he created features and sections — most notably Style, one of his proudest inventions — that were widely copied by others.

During his tenure, a paper that had previously won just four Pulitzer Prizes, only one of which was for reporting, won 17 more, including the Public Service award for the Watergate coverage.

“Ben Bradlee was the best American newspaper editor of his time and had the greatest impact on his newspaper of any modern editor,” said Donald E. Graham, who succeeded his mother as publisher of The Post and Mr. Bradlee’s boss.

“So much of The Post is Ben,” Mrs. Graham said in 1994, three years after Mr. Bradlee retired as editor. “He created it as we know it today.”

(…)

In 1965, The Post had a relatively small staff that included no more than a dozen distinguished reporters. Its most famous writer was Shirley Povich, a sports columnist. Its Pentagon correspondent was on the Navy payroll as a reserve captain. The newspaper had a half-dozen foreign correspondents and no reporter based outside the Washington area in the United States. The paper had no real feature section and provided little serious cultural coverage, but it did carry a daily page called “For and About Women.”

Apart from its famous editorial page (including the renowned cartoonist, Herblock), which had challenged Sen. Joseph McCarthy and vigorously promoted civil rights for African Americans, and which remained Wiggins’s domain after Mr. Bradlee’s arrival, the paper generally had modest expectations for itself, and it calmly fulfilled them.

At the outset, Mr. Bradlee decided “to concentrate on the one thing I did know about: good reporters.” He relied heavily on one good reporter at The Post: Laurence Stern, who proved to be his most important sidekick in the early years. Stern was a wry, irreverent intellectual with ambitious ideas for journalism. Mr. Bradlee named him The Post’s national editor.

Mr. Bradlee brought Ward Just to The Post from Newsweek and soon sent him to Vietnam, where he wrote eloquent, gritty dispatches that undermined the Johnson administration’s public optimism about the course of the war in 1966 and ’67. He hired Richard Harwood from the Louisville Courier-Journal, a brilliant and dogged reporter who became one of the most important editors of the Bradlee era. He found George Wilson, a writer for Aviation Week, who became a distinguished Pentagon correspondent. He hired an old friend from Paris, Stanley Karnow, a Time magazine correspondent in Asia, to be The Post’s China watcher, based in Hong Kong.

Mr. Bradlee’s biggest coup, in his estimation, was hiring David S. Broder from the New York Times. He had to get the approval of Beebe, Mrs. Graham’s most influential colleague, to offer Broder $19,000 a year to leave the Times for The Post. Hiring Broder in September 1966, Mr. Bradlee recalled in 2000, “was of course frightfully important, because then outsiders began to say, ‘Oh my God, did they get Broder? Why did they get Broder? What did Broder see there that we don’t know anything about?’ ”

(…)

Watergate made Mr. Bradlee’s Post famous, but the story that probably made the Watergate coverage possible was the Pentagon Papers, initially a New York Times scoop. Daniel Ellsberg, a disaffected former government official, gave the Times a set of the papers, a compilation of historical documents about U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Times journalists worked for months on stories about them, which began to appear June 13, 1971. The stories created a sensation, even though they contained very little dramatic revelation. After three days of stories, the Nixon administration successfully sought a federal court injunction blocking further publication, the first such “prior restraint” in the nation’s history.

Ellsberg then offered the documents to The Post. Two days after the court order, Post editors and reporters were plowing through the Pentagon Papers and planning to write about them.

The Post’s attorneys were extremely nervous that the paper might publish stories based on material already deemed sensitive national security information by a federal judge in New York. The Post was about to sell shares to the public for the first time, hoping to raise $35 million. And the government licenses of The Post’s television stations would be vulnerable if the paper was convicted of a crime.

The reporters and editors all believed that The Post had to report on the papers. Mr. Bradlee called one of the two friends he kept throughout his adult life, Edward Bennett Williams, the famous lawyer. (The other long-term pal was Art Buchwald, the humorist. The three regularly ate lunch together, boisterously. Williams died in 1988; Buchwald in 2007.)

After hearing Mr. Bradlee’s description of the situation, Williams thought for a moment and said: “Well, Benjy, you got to go with it. You got no choice. That’s your business.”

Armed with Williams’s judgment, Mr. Bradlee called Mrs. Graham, who was hosting a retirement party for a Post business manager. Beebe was on an extension phone. When Mrs. Graham asked his advice, he tepidly said he didn’t think he would publish. She disagreed. “I say let’s go,” she told Mr. Bradlee. “Let’s publish.”

That moment, Mr. Bradlee wrote in his memoir, “crystallized for editors and reporters everywhere how independent and determined and confident of its purpose the new Washington Post had become.” Defying the government in printing those stories proved that The Post was “a paper that holds its head high, committed unshakably to principle.”

The Post did publish, and did end up in court, with the Times. The Nixon administration argued that publication of stories based on the Pentagon Papers could undermine national security, an argument that infuriated Mr. Bradlee. But the Supreme Court ruled 6 to 3 that the government could not restrain the newspapers.

Eighteen years later, the man who had argued the government’s case before the Supreme Court, former solicitor general Erwin Griswold, admitted in a Washington Post op-ed essay that the national security argument was phony.

“I have never seen any trace of a threat to the national security from the publication” of the Pentagon Papers, Griswold wrote in 1989. Mr. Bradlee loved that article, and he carried a copy in his jacket pocket for weeks afterward.

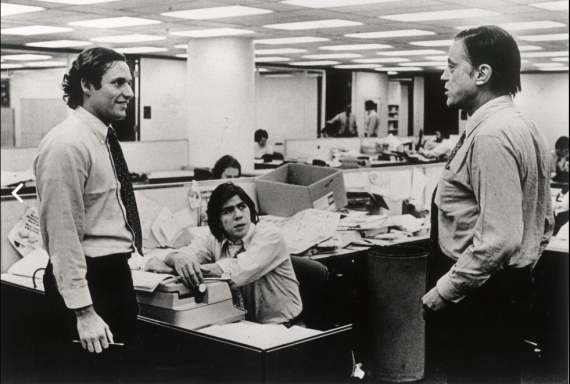

All of that is from, appropriately enough, The Washington Post’s obituary for Bradlee, which is worth a read in its entirety for not only the history of the paper’s triumphs such as the Pentagon Papers and Watergate and Bradlee’s role in turning the paper into a national paper that drove the news cycle rather than just reporting on it but also for the failings under Bradlee, chief among them the the Janet Cooke scandal. That story, you may recall, involved a reporter for the Post‘s story about an eight year old heroin addict named Jimmy that ended up winning a Pulitzer Prize only to have the whole story unravel when it became obvious that the entire story had been fabricated. The Cooke scandal wasn’t the first such scandal in American journalism, of course, and the Times would have their own similar scandal in the future thanks to a reporter named Stephen Glass, but the story did reveal flaws in the way that Bradlee had managed the paper’s newsroom that came as a shock to many given the fame that had come to him and the paper thanks to Watergate and, of course, the move All The President’s Men in which Bradlee was portrayed by Jason Robards, who won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

Bradlee’s impact on journalism isn’t just being remembered by the Post, of course. Here’s how The New York Times summarized Bradlee’s most well-known role in history:

Watergate consolidated The Post’s reputation as a crusading newspaper. A break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex on June 17, 1972 — the White House soon characterized it as a “third-rate burglary” — caught the attention of two young reporters on the metropolitan staff, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward. Soon they were working the phones, wearing out shoe leather and putting two and two together.

With the help of others on the staff and the support of Mr. Bradlee and his editors — and Mrs. Graham — they uncovered a political scandal involving secret funds, espionage, sabotage, dirty tricks and illegal wiretapping. Along the way they withstood repeated denials by the White House, threats from the attorney general (who ended up in prison) and the uncomfortable feeling of being alone on the story of the century.

When the trail of crimes and shenanigans led directly to the White House, Nixon was forced to resign in August 1974. The tapes that he himself had made of conversations in the Oval Office confirmed what The Post had been reporting. Mrs. Graham wrote to Mr. Bradlee in her Christmas letter that year, “We were only saved from extinction by someone mad enough not only to tape himself but to tape himself talking about how to conceal it.”

Mr. Bradlee’s Post and Woodward and Bernstein, as the two became known, captured the popular imagination. Their exploits seemed straight out of a Hollywood movie: two young reporters boldly taking on the White House in pursuit of the truth, their spines steeled by a courageous editor.

The story, of course, became the basis of a best seller, “All the President’s Men,” by Mr. Woodward and Mr. Bernstein, and the book did become, in 1976, a Hollywood box-office hit. Jason Robards Jr. played Mr. Bradlee and won an Oscar for his performance.

In their book, describing meetings in Mr. Bradlee’s office, Mr. Woodward and Mr. Bernstein recalled how Mr. Bradlee would pick up an undersize sponge-rubber basketball and toss it at a small hoop attached to a window. “The gesture was indicative both of the editor’s short attention span and of a studied informality,” they wrote. “There was an alluring combination of aristocrat and commoner about Bradlee.”

They observed that double-edged manner in Washington society, sometimes seeing it displayed in one swoop, as when Mr. Bradlee would “grind his cigarettes out in a demitasse cup during a formal dinner party.”

“Bradlee,” they added, “was one of the few persons who could pull that kind of thing off and leave the hostess saying how charming he was.”

After Watergate, journalism schools filled up with would-be Woodwards and Bernsteins, and the business of journalism changed, taking on an even tougher hide of skepticism than the one that formed during the Vietnam War.

“No matter how many spin doctors were provided by no matter how many sides of how many arguments,” Mr. Bradlee wrote, “from Watergate on, I started looking for the The l

By all accounts, Bradlee was note always the easiest person to work for and, as I noted above in reference to the Cooke story, his management style sometimes led to problems or ignored the problems as they were developing. For the most part, though, Bradlee was without a doubt the most important newspaper editor of the later half of the 20th Century, and arguably one of the most important figures in modern American political journalism. In addition to taking on the government and winning in the Pentagon Papers case, a decision which led to a Supreme Court ruling that to this day stands for the important proposition the prior restraints on speech are almost always unacceptable and that the government would bear a heavy burden in attempting to use “national security” as a justification for trying to stifle press scrutiny and Freedom Of Speech, he played a crucial role in pushing forward a story that other editors might have ignored or shied away from. The Watergate scandal started out as just a break-in at an office complex near the banks of the Potomac, but it was two Post reporters, who didn’t even cover the White House, who sensed that it might be something more. Under Bradlee’s guidance, and his insistence that they verify their sources before proceeding with a story that quickly had the implications of being something far more than just a break-in and eventually led to the biggest political scandal in American history and the resignation of a President. More importantly, as Bradlee himself says in the line that ends the blockquote above, it helped to change forever the way Americans perceive their government and political institutions and took off the rose-colored glasses that, quite honestly, had been distorting reality.

Many have tried to copy Bradlee, as well as Woodward and Bernstein in the years that followed, and it goes without saying that the three of them changed American journalism significantly. What was once a “buddy buddy” relationship between the press and people in power became a far more adversarial situation, and as a result there was far more reporting about scandals, as well as far more willingness on the part of the media to publish material provided by anonymous sources even when that information is classified. There are some parts of those developments that are worthy of being criticized and questioned, of course, but for the most part is a far better world than the one in which journalists seemed to be far more passive in dealing with the government, a passivity that essentially allowed something like the Vietnam War to happen with very few of the reporters covering it actually questioning its wisdom until it was far too late to do anything about it. For changing that culture alone, Bradlee and those he worked for deserve our thanks.

Great man.

The country is better because of him.

How many of us get to say that ?

May he rest in peace.

Doug, it seems you cut off the end of Bradlee’s quote in the block quote. As to this:

Iraq.

Excellent write up, Doug, for a great newspaperman. We may not see his like again.

@stonetools: We also may not see newspapers around much longer. The professional investigative reporter that was inspired by people like Woodward and Bernstein is now almost a thing of the past. What we have now is the sound bite, opinionated, “breaking news” junk that is called news. The local news is now basically a talk show with kinds of warm fuzzy, feels good “news”. A spot about a local barbecue contest ? Come on. And the giggly, happy talk anchors that often talk to each other more than report stories. Sickening ! I remember as a child staying up on Friday nights watching the 11:00 news. You had news, weather, sports in that order, with a separate anchor doing each, or sometimes the same person doing all three. None of the back and forth happy chat between the three anchors. And after the 11:00 news on Fridays, we would watch the Friday night scary movie! Nothing like it now. Those days are gone forever.