Democracy and Institutional Design III: Towards a More Complex Discussion of Democracy

Part III is here (a lot sooner than Part II was).

The series so far:

- Democracy and Institutional Design I: A Basic Preface on Regime Type

- Democracy and Institutional Design II: A (Very) Basic Definition of Democracy

A preface to part III: please recognize what is probably obvious, that this is a general discussion of topics that could certainly be dealt with in a book-length fashion and that any number of digression are possible (and, likely necessary). My goal here is to provide a better foundation for conversation as well as a basic explanation of where I am coming in my writings on this topic.

Another important caveat is that I am more than aware of the shortcomings of democratic governance. When I quoted Churchill in the previous part of this series, or when I noted the aspirational nature of democratic governance, I was sincerely noting imperfections. Government is necessary and some forms of government are better for the governed than are others, however. I am, to return to a another quotation, profoundly aware that people are a problem.

As I noted as more or less a “PS” at the end of Part II, I will put up front here in Part III. If you are going to pull any version of the “republic v. democracy” bit in the comments, please see here first. One could also consult A “Republic v. Democracy” Lexicon.

III. Complex Democracy.

“Complex democracy” is not a term of art so much as simply my attempt in these posts to create a level of distinction within the conversation. In the previous post I defined “simple democracy” in terms of co-equality of the participants (at least in the sense that each voter’s vote is equal) and that decisions would have to be made by majority rule at least. In short, a simple system is one wherein co-sovereigns could exercise their share of power. I also wanted to introduce the notion of “simple” (if not simplistic) definitions of democracy because a lot of criticisms of democratic governance (or defenses of anti-democratic practices) usually use a simple definition (majority rule voting) as a straw man.

The reason for using the modifier “complex” is pretty straight-forward: the actual functioning of a democratic polity is complicated. The title of this series is “Democracy and Institutional Design” and the bottom line is that while “democracy” may simply mean power by the people, the mechanism (“institutional design”) that would allow this to take place is not simple in the least.

Of course, any discussion of more complex democratic governance assumes not direct democracy (where the people literally directly govern) but rather representative democracy wherein the voters, as the principals who hold sovereign power, would elect a government to serve as the agents of the people for a set amount of time. This distinction between direct and representative democracy is, by the way, as I have stressed for years, the distinction Madison was making in the Federalist when he contrasted democracies with republics.

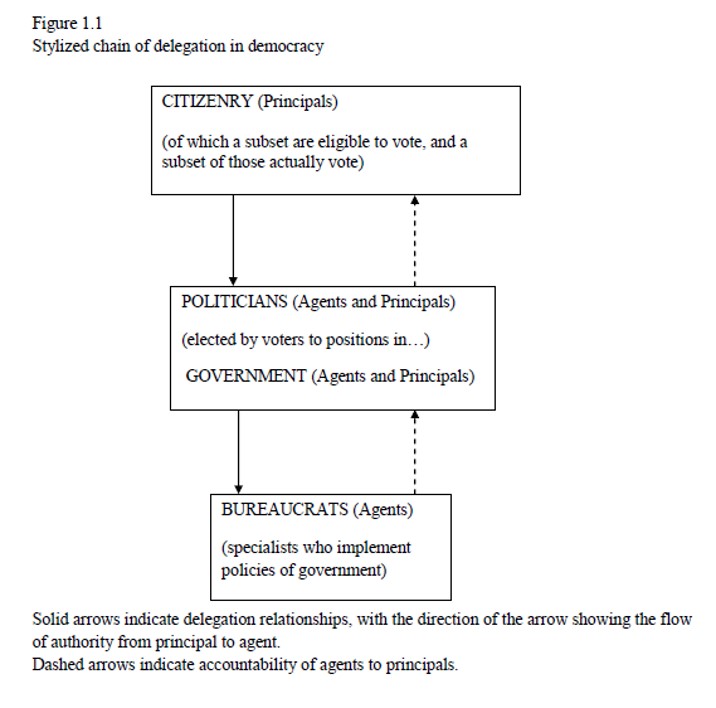

A basic model of representative democracy looks like this (from Taylor, et al. 2014):

The idea being that the elected government should serve as a the agent of voters-as-principals who hold the ultimate power. Of course, any principle-agent relationship has problems because it is impossible for the agent to perfectly represent the principle (more on that later when we talk about electoral rules). And when both the principle and the agent is collective, with various and varied interests, this gets all the more complicated with any number of possible distortions that can occur in terms of delegation and authority. Note that the government, as chosen by the voters, runs the bureaucracy. Direct democracy would merge the first two boxes into one.

In the simple democracy of part II of this series, one might conceive of a situation in which the bare majority (maybe even a plurality) could control the totality of the second box above, which could be problematic if that plurality abused its position. This is a classic “tyranny of the majority” situation that is often discussed (see, e.g., Mill, among others, about this problem). However, when we start talking about the complex democracy I am describing this portion, such a simplistic majoritarianism (or pluralitarianism) is not really possible.

As I often stress when I write about this topic, no democracy in the world is governed by a system of simple majority rule. One could make a partial argument that the closest one can find to such a system is the Westminster Model of democracy (so named because the British Parliament is housed in the Palace of Westminster). In such a system there is two-party competition for control of a unicameral parliament which, in turn, selects the executive (the PM and cabinet). An unwritten constitution means that whatever the majority of parliament wants is, by definition, constitutional. Under such conditions the party that can win the plurality of the popular vote (for reasons that will just have to be accepted for the moment for the sake of conservation) can capture a majority of seats in parliament, and therefore total control of government for a set amount of time (a max of five years between elections in the UK with early elections being possible). It should also be noted that the UK has a unitary state insofar as local governments do not have policy independence from the central government which enhances the power of the party that control the House of Commons. This is a quick and simplified version of what one can find in Chapter Two of Lijphart 2o12 (references below). And, of course, my simplified description does not address things like the fact that UK doesn’t have a pure two-party system, the ability of the House of Lords to delay legislation, nor the devolution of power to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland (which clearly blunts the unitary nature of the state). There is also a tradition of protection of certain civil liberties in the UK that protects against government action in those areas. In short, even the Westminster model is more complex that the simple, straw man version of democracy that many deploy.

Beyond that, however, the prevalence of the Westminster model in the world is quite limited. If we look (as my co-authors and I did in A Different Democracy) at the largest democracies with some amount of longevity (31 cases), we find that really only the UK comes close to fitting the Westminster model in that sample. Even if we expand to smaller examples in Lijphart 2012, we find only places like former British colonies such as Barbados (and it existed in New Zealand until they reformed their electoral system in 1993).

Once we add in any of the following to the Westminster model it breaks down: federalism, bicameralism, a separately elected executive, constitutional review by the courts, and/or a multi-party system (among other possible institutional variations). Each of these affects the degree to which the plurality can directly control the state.

And this is where things get truly complex. “Democracy” in the modern sense does not mean simplistic majority rule. It means attempting to translate the collective will of the populace into control of government and it requires a suite of institutional choices. The ability of that government to act, in general is frequently curtailed by the fact that power is shared by various actors and institutions.

So, democracy becomes increasingly complex as an institutional form when power is distributed among various institutions (e.g., bicameralism, presidentialism, and/or federalism). It is also important to note that all definitions of representative democracy assume that there are a number of key protections for individual rights. You cannot, for example, have democracy without things like freedom of speech and press, the right to assemble, and freedom of conscience. There rights cannot (or, at least should not) be abridged by majority rule. We should acknowledge that abuses on power do exist, however.

For example, let’s consider the ten variable from Larry Diamond’s (1999) definition of “liberal democracy” (as I summarized them in Taylor 2016):

| Institutional Design and Function |

| 1. Control of the state lies in the hands of elected officials. |

| 2. Executive power is constrained. |

| 3. Electoral outcomes are uncertain, with a presumption that some alteration of the party in power will take place over time. |

| Civil Liberties |

| 4. Minority groups are not prohibited from expressing their interests. |

| 5. Associative groups beyond political parties exist as channels of representation. |

| 6. There is free access to alternative sources of information. |

| 7. Individuals have substantive democratic freedoms (speech, press, association, assembly, etc.) |

| Judicial/Legal System |

| 8. Citizens are politically equal under the law. |

| 9. Liberties are protected by an independent, nondiscriminatory judiciary, whose decisions are respected by other institutions within the state. |

|

10. Rule of law is sufficiently strong to prevent “unjustified detention, exile, terror, torture, and undue interfere in their personal lives not only by the state but also by organized nonstate or antistate forces” (1999:12). |

One will notice that most of these elements have nothing to do with majority rule, but rather are protections of citizens from governmental power/the arbitrary abuse of power by others in the society. See, also, Dahl 1971 and 1998 for further reading.

The bottom line is that whenever I talk about democracy in the modern world, I am speaking in the realm of the kinds of complexities noted in this post. Real democracy is complex, has to deal with multiple actors and processes (which will eventually address when I talk about veto gates and veto actors), and takes individual/minority rights very seriously.

I would also note that this about defining the regime type itself, and is focused on how the popular sovereignty is translated into governing. The quality of such government, especially in terms of things like reprentativeness is its own discussion. For example, majority rules has to be an element of things like legislating but in the context of the other protections noted above.

To be continued (tentatively line-up for now):

Part IV: A Digression on a (the?) Problem with Popular Will.

Part V: Talking about Electoral Rules.: Seats and Votes.

Part VI: Veto Gates and Veto Actors

Part VII: The Pathologies of American Democracy,

Works cited

Dahl, Robert A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dahl, Robert A. 1998. On Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Diamond, Larry. 1999. Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lijphart, Arend. 2012. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries., 2nd edition. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty.

Taylor, Steven L. 2016. “The State of Democracy in Colombia: More Voting, Less Violence?” The Latin Americanist. (June): 169-190.

Taylor, Steven L., Matthew S. Shugart, Arend Lijphart, and Bernard Grofman. 2014. A Different Democracy: American Government in a 31-Country Perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ummmm…. Part II was here before part III and by definition was here “sooner”.

(inner pedant ducks and runs)

At one point you write:

That seems like a typo.

Nicely done. I like “complex democracy” to avoid all the silliness around “republic”. Also I’m big on Monet.

@Ratufa: It was–thanks for noting that. It is now fixed.

The last “agent” should say “principle”

I have deep and abiding love for The Ronettes. Love, yes, in full understanding that Phil Spector was a supremely shitty person way before he actually murdered someone.

Ronnie (nee Veronica Bennett) was a heaven-sent angel. A goddess. Who shimmies!

She can whoah ohh better than anyone else ever.

Be My Baby

https://youtu.be/NnWOBMQhNBQ

This is a cool vid because it is a compilation of a bunch of live shows. So much goodness and shimmying. At the 2:00 minute mark there is just the best shimmy dancing ever.

Recommend also Walking in the Rain, etc.

Also, when Christmas comes, the very best Xmas album ever is called A Christmas Gift For You with The Ronettes, The Crystals, and others. Xmas classic songs in Wall Of Sound girl group style. You’d be a total Grinch to not check it out.

Here is something from Joe Meek, who is sort of English the analogue to Phil Spector. Instrumental ur-surf+techno from 1962.

This is The Tornados doing Telstar

https://youtu.be/WPDvsLSnUGc

The Tornados were the backing band for Billy Fury.

And it’s just a name coincidence – her last name is really Specktor, here is Regina Specktor. I love Better. I love Samson. Solid, awesome anti-folk piano driven songs, but That Time is quirky cool profound drums and bass.

Regina Spektor – That Time

https://youtu.be/05MRbZvzFsw

So cheap and juicy!

You cannot make a bad choice with Regina Spektor. She writes good songs, and wraps them in cool, bright, fun, absurdist videos. She’s the female Lloyd Cole – there are no bad songs in the catalog. Every song – that’s reaaallly hard and quite remarkable.

Since it’s relevant, here’s Lloyd Cole’s Jennifer She Said

https://youtu.be/SgKYTYUGChc

The video has a lot of ’60s English cafe racer imagery. Basically, these were the people who would get in street fights with the mods.

God damn! I love Lloyd Cole – that dude shoulda been a world-wide rock star.

There are at least a dozen amazing Lloyd Cole songs that should have been monster hits. He should be rubbing elbows with Bono. Knighted, even – Sir Lloyd.

Joe Henry should be a touchstone. There is no song on Short Man’s Room that isn’t an absolute gem. Yeah, he’s Americana, so fairly niche, but at least Jeff Tweedy big or The Jayhawks big.

Dude deserves better.

Actually, The Jayhawks were the backing band on all of the Short Man’s Room songs. (Hey! I know those dudes!)

Joe Henry. One Shoe On

https://youtu.be/DRPsUGplmYM?list=OLAK5uy_n-JbyqpMAsmqZEe6ZwgOlfGx-j0ZGFS3k

He’s Madonna’s brother in law. Which is quite odd.

vs.

I’m not trying to be snarky here, Steven, but this sounds like a contradiction to me. If there are higher principles and authorities that “the will of the people” must bend to, then either it isn’t democracy or your definition of democracy quoted above is incorrect.

As you have noted in this series, “the will of the people” was OK with slavery and women as chattel for a big chunk of US history. Either we weren’t a democracy, or democracy can include such things.

Diamond’s criteria seem like yet another attempt to borrow the cachet of the word ‘democracy’ and apply it not to a system of government, but to a set of values. I can agree with the values while still flagging this as sophistry; his notion of “liberal democracy” is actually just a definition of “liberal government”. It’s the ‘liberal’ part that is doing the heavy lifting. The extent to which democracy can support liberalism is an open question for purposes of this discussion, I would think.

@DrDaveT: The fundamental conundrum of democratic governance is that it has to balance multiple values, which includes determining when using majority mechanisms is appropriate (such as regular legislation) and when it isn’t (determining the application of basic rights).

But, really, politics in general is about balancing values.

When the US was enslaving people and denying woman the right to vote, it really wasn’t a democracy–even if the word was used. An argument could be made that for the time it was more democratic than a given monarchy, but there is no way in the world we would classify a country that denied half its population the vote, or has slavery as a “democracy.” Some authors (including Dahl’s 1971 book that I cited) points out that one could argue the US was not fully democratic as long as it was systematically denying African-Americans the right to vote.

Likewise all of this fits into the aspirational nature of democracy I noted in part II.

@DrDaveT: And yes, the word “liberal” is pretty important. Democratic governance is, for all practical purposes, a manifestation of classical liberalism.

Illiberal democracy is a terms that some use (I am not sure that such cases are actually democracies, but that is another discussion).

@DrDaveT: I think the objection that you mention is covered by the opening observation that “people are the problem.” Locke, for example, seemed to have no illusions about democracy being morally superior to other forms except to the extent that the people forming the democracy were morally superior. Churchill, Diamond, Dr. Taylor all seem to be presuming that when we use the term “democracy,” we are talking about majority rule to the benefit of the whole society rather than simple majority rule to the benefit only of those in the majority. What Aristotle might have termed a “polity.”

ETA: “…one could argue the US was not fully democratic as long as it was systematically denying African-Americans the right to vote. In which case, the argument might be made that the US is STILL not a democracy.

@just nutha:

As I was reminded this morning, the Economist recently reclassified the US from “democracy” to “flawed democracy”. Freedom House also downgraded the US recently.

Beyond that, there has long been room to critique the democratic quality of the US.

@just nutha: @DrDaveT: In general I would note that I am trying to describe both theory and reality (which don’t fully overlap). The reality part is that the rules used to determine who governs matter greatly, as well as the rules which determine what the government can do to the governed.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Sure. Understood.

At the same time, I’m trying to avoid the all-too-frequent confusion between the means and the ends, and which label applies to which. Democracy is a way of deciding who gets to make the decisions for everyone. Any claims that this means will tend toward certain desirable ends require further justification, be it logical or empirical. And the question of which ends are in fact desirable is wholly independent of the question of which means might best get us there. For instance:

I disagree in part. This is, at best, a contingent and accidental historical fact. The classical liberals advocated democratic governance either because they genuinely thought that it would necessarily achieve liberal goals, or because they couldn’t think of anything better in their rejection of traditional monarchies and despotism. I suspect that if Locke or Rousseau or Madison or Smith had thought that a particular non-democratic system were bound to secure the blessings of life, liberty, and property to all, they’d have chucked democracy in a heartbeat in favor of that system.

I’m also going to quibble with your notion that pre-suffragism US was not a democracy. Every democracy restricts the franchise; it’s a sliding scale. Those under 18 years of age remain disenfranchised in the US, as do the mentally incompetent, certain convicted criminals, non-citizens, pets, corporations, etc.

No democracy in the world is going to give the vote to 3-year-olds; where one draws the line is a function of many things. Nineteenth century liberals denied the vote to women for the same reasons we deny the vote to toddlers and the insane. We think they were wrong — but not because they chose to restrict the franchise. We just think they drew the line in the wrong place.

@Steven L. Taylor:

No, I think it’s the same discussion. You want democracy to always be a good thing, so you’re stacking the deck.

Pure tyranny of the majority, as described by Mill, is both clearly democracy and clearly a bad thing. And it’s not hypothetical — democratic societies have voted to persecute the minority at various times over the centuries, even if you restrict consideration to the enfranchised subset of the society. I think it’s important to be clear that this doesn’t mean those weren’t really democracies — it means that democracy isn’t really the thing we care about most.

@DrDaveT:

Quite likely so, but the practical point is that no such alternative has emerged.

@DrDaveT:

I do have a normative preference for democracy over the alternatives, yes.

I simply think (and you are free to disagree, of course) that a system that is ultimately tyrannical isn’t democratic by definition.

Perhaps the solution is say that I am focused on liberal democracy–but that is usually what the literature means by the term.

@DrDaveT:

It was democratic for its time, if you like. And yes, there are currently limitations on suffrage.

But limitations by age, to pick the main one from your list, is not unreasonable (we can quibble over whether 18 is the right cut-off, of course). By that is categorically different than limiting based on gender or race.

We have a problem with felony disenfranchisement, IMO, BTW.

If a majority can tyrannize (and it is likely a plurality) you move into oligarchy as far as I see it.

No basic rights, no democracy.

Just voting is not what makes a system democratic.

At the federal level, those in power were elected by a minority and they certainly seem to be doing everything they can to tyrannize others…

@An Interested Party:

And there is a reason I keep being critical of the electoral college and why I have profound problems with the Senate (and why I am critical of the representativeness of the House).

So you see no conceivable middle ground between “the will of the people” and tyranny? Really? Which of those do you think we’re currently living under? In particular:

So, there is no tweak to our current system that you think could achieve the goals of liberalism? You’re more of a radical than I thought :-).

@Steven L. Taylor:

No society ever thinks that their restrictions on the franchise are unreasonable. Unless you have some other objective standard that you can appeal to, ‘reasonableness’ isn’t going to help.

But, as noted in the other thread, “one person one vote” isn’t my mantra, it’s yours. I’m more concerned with the fact that “the will of the people” can be illiberal, or even evil. That forces a choice between democracy (as you define it) and liberalism. I personally choose liberalism over democracy — I don’t care about “the will of the people” per se. I’ve seen what it can be like.

Now, as I said before, I’m willing to hear an argument that no form of government can ensure that liberal values will be honored in the long term, and that “the will of the people” offers the best bet of a bad lot. But, again, I think that strong claim requires some explicit argument beyond mere assertion.

@DrDaveT:

I am not sure how you get that from what I said.

I really do not understand where you got that from.

Are you operating under the assumption that I think that the US system is the ideal type of democracy?

@DrDaveT:

This is not unfair, but let’s try this this way.

What is the case that you think looks like liberalism without elections in the post WWII era?

What is the case that you think fits the description of democratic, but illiberal?

I am trying to lay out some general ideas which, as I noted in one of the recent posts, could be books (so I am not pretending to address all that could be presented). I am working towards an ability to discuss concrete cases.

You have provided a lot of hypotheticals and criticisms that I do not necessarily disagree with, but ultimately most of them lead to fantasy regimes that do not exist (and I not sure can exist).

Also: yes, masses can make mistakes and be tyrannical. Sometimes nothing you can do will stop that–but so can smaller numbers of people. Indeed, history shows us that the smaller number of people running things models frequently leads to tyranny.

Part of the point, by the way, of trying to construct the basic ideal type of democracy is not to say, hey look how ideal democracy is, it is so one can then note how reality deviates from the ideal type.

Perhaps you misunderstand what I am doing here (or perhaps I am being unclear). I am not providing a real world discussion of what democracy is in the senses that I think that all democratic governments are perfect. Far from it! I am trying to lay out a working theoretical definition so that we can then use it to critique reality.

Spoiler: the US doesn’t measure up in a lot of ways.

@DrDaveT:

I was thinking about our interchange. Maybe the following will help:

1. The whole point of this series is to provided background and information to talk about a real world regime type: representative democracy, especially since the end of WWII. So, part of why I stress voting is because voting (and the electoral rules used) are essential parts of those real regimes.

2. Sure, people can be horrible, and yes: democratic tools can be used (and have been used) to lead to nondemocratic outcomes (Venezuela comes to mind).

3. So, sure, in the abstract if we are choosing between a regime without voting, but is otherwise liberal and a regime with lot of voting, but with thoroughly illiberal outcomes, I am choose the non-voting option.

4. But, as a practical matter, the regimes that have been able to maintain some semblance of liberalism also do so with voting as an essential element of their regime machinery. Again, hence my focus (especially since I want to talk, eventually, about the real world and not just abstractions).

Also: to repeat/clarify something I said earlier: I am not suggesting that real world democracy is a manifestation of the ideal type that I have been discussing. I fully acknowledge the lack of rainbows and unicorns.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Either of those is possible. I think these last 2 responses from you help a lot, though. Let’s see if I can reciprocate equally effectively.

I can say up front that I never thought that you were claiming that all democratic governments are perfect. What I did think you were trying to do was to separately analyze the role of democracy in liberal democracy from the role of liberalism in liberal democracy. If I was wrong about that, it would explain a lot.

I also feel like you keep switching back and forth between a definition of democracy that involves “the will of the people” and a definition that involves elections. For example, when I talked about choosing between democracy and liberalism, you replied:

I would have expected you to ask “what is the case that looks like liberalism, but not like the will of the people?”. If you were limiting discussion to actual historical governments, I would admit the link between liberalism and elections — but you explicitly said you are discussing an ideal type of democracy. (But see below.)

I think this may be the key:

I had thought that the point was to explore the possibilities and limitations of democracy as a vehicle for achieving liberal government. That question interests me greatly, as does the converse question of whether there are non-democratic* forms of government that could do at least as well at achieving liberal government. I’m also interested in the side question of whether there are forms of democracy that do better at reflecting “the will of the people” than one-person-one-vote systems do.

I’m interested in actual historical governments mostly only to the extent they illuminate those questions. The common role of voting in those historical governments is a bug, not a feature, when I try to tease out what is driving outcomes.

I am trying to push back on your equating ‘historical’ with ‘real’. The government we have was just an abstraction, until we did it. It is very much a feature of the real world now. I am interested in what is possible and practical, as opposed to what is historical.

*Using your definition of democracy as government intending to implement the will of the people, any government that deliberately subordinates the will of the people to some higher standard is necessarily non-democratic.

@DrDaveT:

I was not. Hopefully Part III makes that clear.

Well, when I say “historical cases” I mean up and until the present moment. The only way to gather data for the kind of conversion we are having is to look at history.

The bolded part makes zero sense to me.

Well, if events that have happened are not real, I am not sure what reality is.

Which is what makes it both “real” and “historical.” Prior to that it was a pure hypothetical, and largely without anything to comparative it to.

I feel like you are using the word “historical” differently than I am. The 2016 election, for example, which would be a data point in a discussion like this is now part of history, i.e., an event not happening now, but which happened in the past.

In regard to voting: the reason I keep linking voting to all of this is that, as a practical matter, that is the main mechanism for measuring popular will.

I think you keep trying to unduly box me is as saying that my definition of democracy is the will of the people. I did not intend that to be the essential definition (nor do I think I did). And really, in a representative democracy one is really looking more from an appropriate representation of multiple wills because there probably is no singular “will of the people.” Again, I intend to talk about that in Part IV (indeed, note that I have tentatively entitled Part IV as follows–and did so before our conversation–“A Digression on a (the?) Problem with Popular Will”).

And I do not see why certain first principles cannot be put into place (e.g., I cannot be deprived of liberty with due process) and still say you have democracy (especially since to enjoy democratic citizenship entails freedom from arbitrary imprisonment).

@DrDaveT:

While I address this above, let me carve this out further and point out that no actual governing system that would be defined as democratic has not featured elections.

Elections are essential to any discussion of actual, functioning democracy, even if elections alone do not define democracy.

I am utterly unclear as to why you want to put elections to the side as if they are incidental, rather than central, to the conversation.

@DrDaveT:

One more carve-out. I understand that this is the purpose for your questions, but I am not sure why you think it is the purpose of the series. After all, the title of the series is “Democracy and Institutional Design” and the first sentence of Part I starts as follows: “I have long intended to write a series of posts about representative democracy and institutional design…”

The question of whether you can have liberalism without representative democracy is an interesting one, but it strikes me as wholly abstract, since one would have to invent such a governmental form.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Looking back, I see that I grossly misread your statement “Democracy is imperfect and it does not live up to its promises (e.g., being the “will of the people”).” from Part 2. Mea culpa; that has led me into confusion.

However, I think you did me the return favor with:

If you want to understand the effect of X on Y, you need data points that vary in X. If everyone uses similar systems of voting, you don’t get any information about how using such a voting scheme affects outcomes. It’s not a bug for the societies in question; it’s a bug with respect to being able to do statistics or causal analysis.

As for ‘historical’, there are three kinds of systems of government:

1. Systems that have been tried in the past (historical)

2. Systems that have not been tried yet, but could work (possible and practical)

3. Systems that have not been tried yet, and would not work (possible but impractical)

4. Systems that could not be implemented (impossible)

Category 1 systems are the only source of empirical data, but that doesn’t mean we don’t know a lot about categories 2 and 3. (Category 3 includes Libertarianism, for example.) Given that any improvements in the future will have to come from Category 2, shouldn’t it be included in the conversation?

@Steven L. Taylor:

Fair enough — though inventing a hitherto wholly abstract system of government is exactly what the Founding Fathers did. In that sense, realizing abstract systems is also ‘historical’, and the voting mechanisms that seem natural to us now were just as outlandish then as the rest of the package was.

Are you more interested (in this series) in the flip side — what are the limits on liberalism within the strictures of representative democracy? I’d be interested in that, too.

@DrDaveT: I did misread you “bug” comment, yes.

Yes, we can talk about #2 (and even #3 and #4), and that can be interesting, fun, and even lead to breakthroughs. I am not opposed to such discussions. My main goal here, however, is ultimately grounded in #1 insofar as I, personally, am interested in, as the series title suggests, the interaction between institutional design and democratic outcomes (broadly defined).